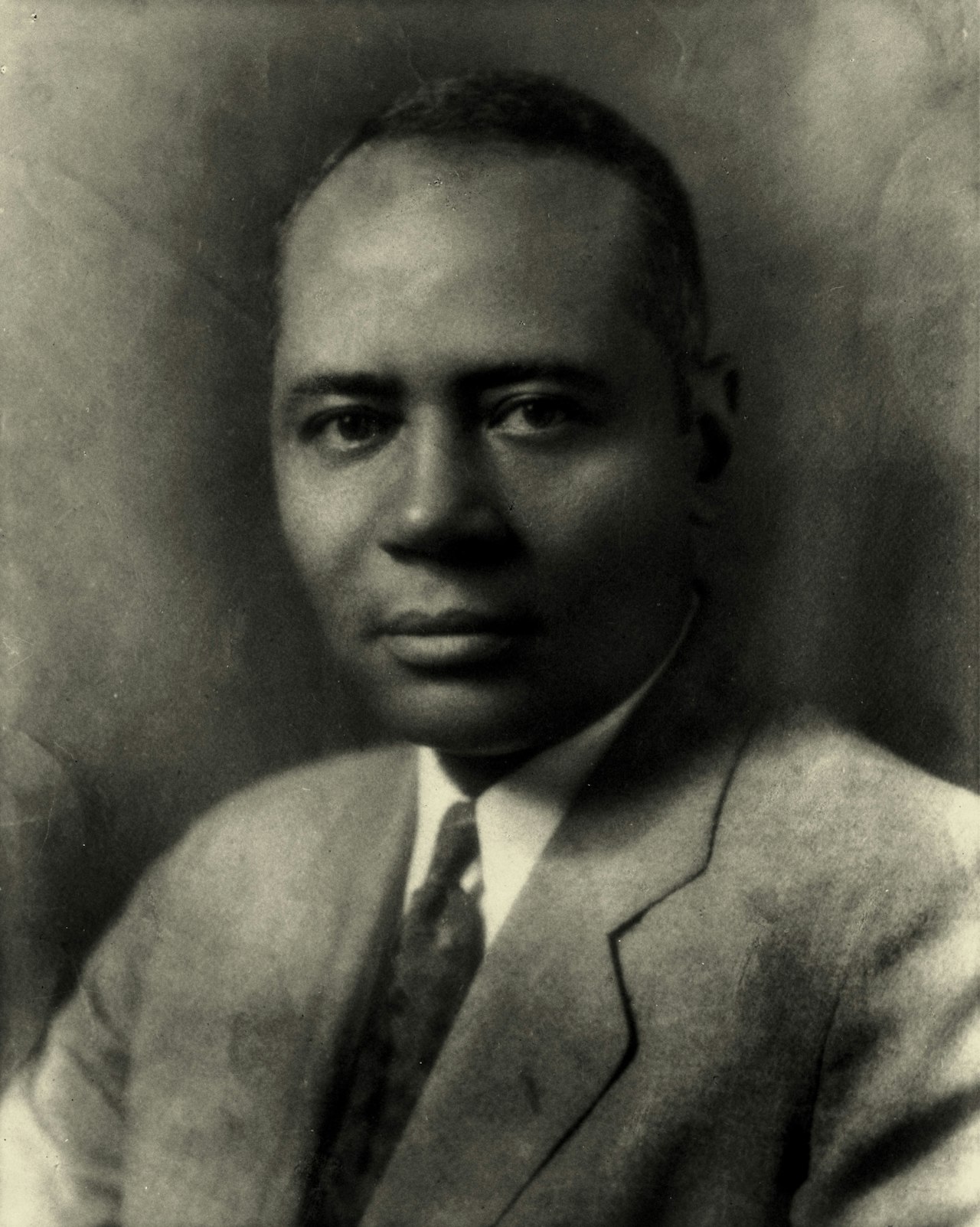

Charles Hamilton Houston

"The Man Who Killed Jim Crow"

Charles Hamilton Houston entered Harvard Law School at the tail end of the “Red Summer” of 1919, a violent period of nationwide racial and social unrest during which Black Americans lost hard-won legal and political gains while experiencing deadly white-on-black violence, especially against Black soldiers returning from World War I. The period also marked one of the first times in U.S. history in which Black communities fought back against such attacks.

Taking a Stand for Others

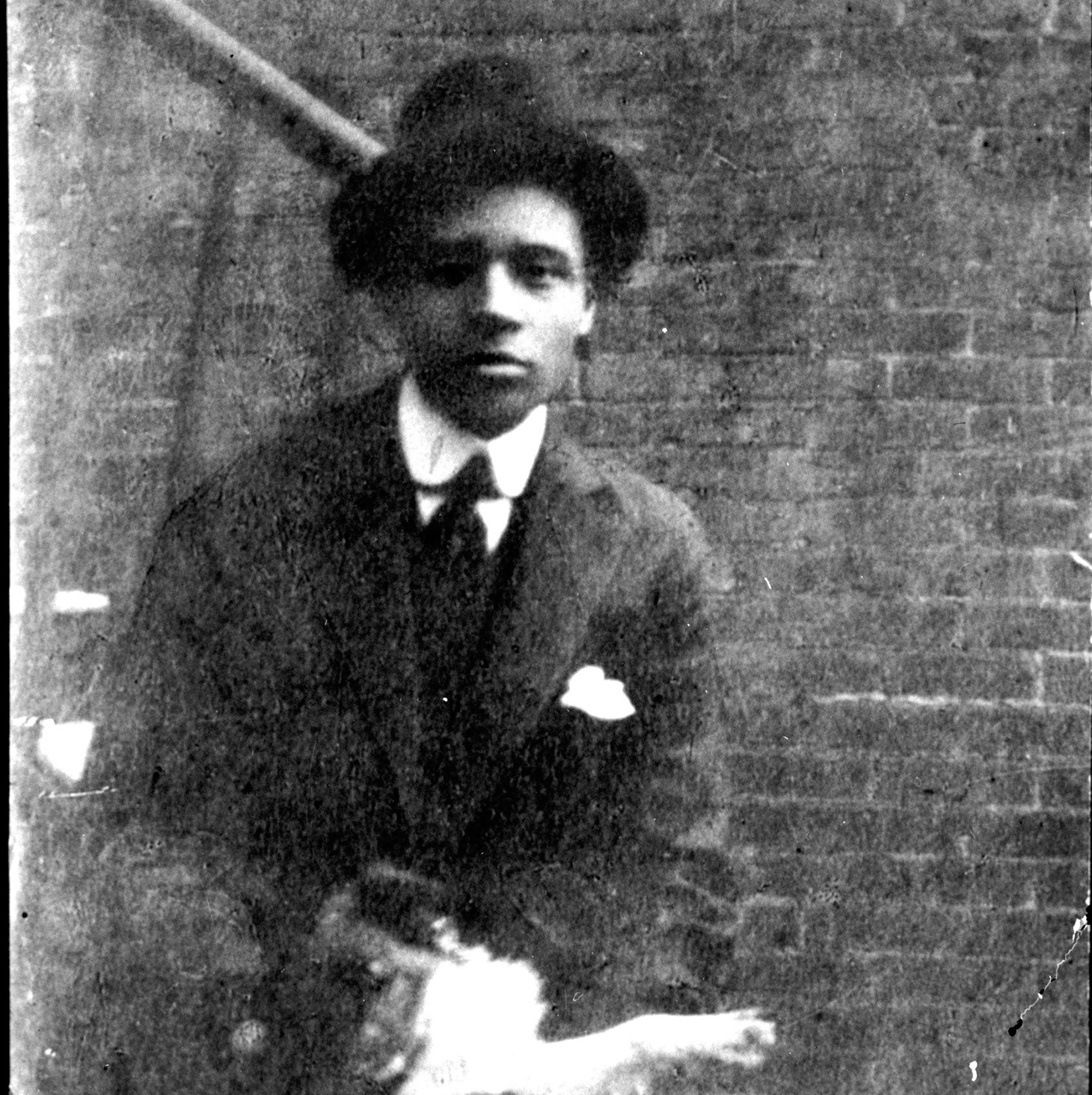

Born in Washington, D.C. in 1895, Houston enrolled in Amherst College at the age of 16, and was the only Black student in his class. He earned his bachelor’s degree, magna cum laude in 1915 and was elected to Phi Beta Kappa. After teaching in Washington, D.C. for two years, Houston joined the then-segregated U.S. Army as an officer. He left in April 1919, just before the Red Summer began.

“The hate and scorn showered on us Negro officers by our fellow Americans convinced me that there was no sense in my dying for a world ruled by them,” Houston later wrote. “I made up my mind that if I got through this war, I would study law and use my time fighting for men who could not strike back.”

When Houston entered Harvard Law School that fall as one of a handful of African Americans, he held the fervent belief that integration was key to the social, political, and economic success of Black Americans. “I pray that the Negro will make sure that the system which shall survive in the United States . . . guarantees justice and freedom for everyone,” he said.

Paving the Way

Houston flourished at Harvard Law School, earning top grades and a coveted position on the editorial board of the Harvard Law Review, the first Black student to do so, decades before future-US President Barack Obama would become the first African American elected president of the prestigious journal. Houston’s confidence and exemplary work caught the attention of Professor Felix Frankfurter and Dean Roscoe Pound. He also won the respect of his fellow students, and many of his Black classmates saw him as a leader.

Houston earned his Doctor of Juridical Science in 1923, the first year that Harvard awarded the SJD, becoming the school’s first Black SJD graduate. With support from his professors, Houston secured a Sheldon Traveling Fellowship, which he used to continue his studies and earn a Doctor of Civil Laws degree from the University of Madrid.

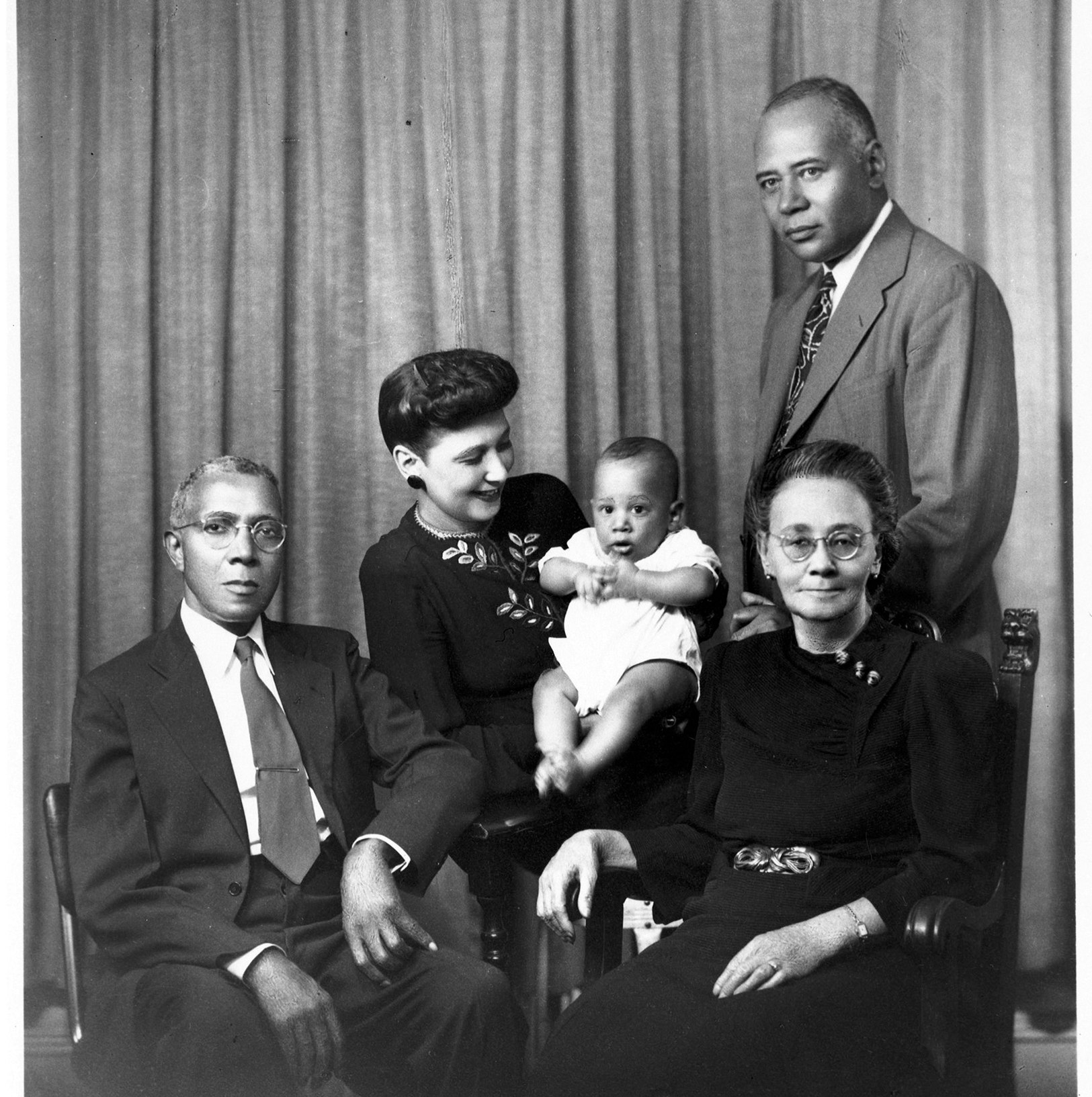

Houston & Houston

Houston’s experience of injustice at home and abroad prompted him upon his return to Washington to join his father’s law practice. Renamed Houston & Houston, it was one of the first Black law firms established in Washington, D.C. Houston fervently believed that it was incumbent upon Black lawyers to fight for Black people and Black communities because “the average white lawyer especially in the South could not be relied upon to wage an uncompromising fight” for the equal rights of African Americans. When the American Bar Association refused admission to Black lawyers, Houston and others founded the Washington, D.C.-based National Bar Association.

He also taught part-time at Howard Law School, and in 1929, Howard’s first Black president, Mordecai Johnson, appointed Houston to serve as the law school’s vice-dean, though he fulfilled many of the responsibilities of dean. Houston transformed what was then an unaccredited part-time evening program into what Columbia University law professor Jack Greenberg once described as the “West Point of civil rights training.”

Houston’s protégés at Howard included Thurgood Marshall—who would later found the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund and become the first Black justice of the United States Supreme Court—and the Harvard-educated lawyer Oliver W. Hill, who worked together to win the historic case of Brown v. Board of Education that made segregated, “separate but equal” schools unlawful. Their success was not only a matter of rigorous training from Houston; the Brown victory was also built upon legal foundations laid by Houston in his own successfully-argued cases.

A Foundation is Laid

Houston left Howard in 1935 to serve as the NAACP’s first general counsel, establishing a precursor to Marshall’s Legal Defense and Educational Fund. He made it his mission to disprove the fallacy of “separate but equal” and launched a campaign by Black lawyers around the nation to expose the glaring inequities that Black Americans faced in virtually all aspects of their lives, but particularly education. To make his case and attract people to his cause, Houston traveled throughout the South documenting these inequities on film, and delivered speeches across the nation.

Discrimination in education, Houston argued, “is symbolic of all the more drastic discriminations which Negroes suffer in American life. And these apparent senseless discriminations in education against Negroes have a very definite objective on the part of the ruling whites, to curb the young [Blacks] and prepare them to accept an inferior position in American life without protest or struggle.”

Houston, who has been called “the man who killed Jim Crow,” also won major cases affirming the civil rights of Black Americans in other areas. Of the eight cases that he argued before the U.S. Supreme Court, he won seven.

Honoring a Legend

Houston died in 1950. He did not get to argue Brown v. Board of Education or celebrate the historic triumph.

In 2005, Harvard Law School professor Charles J. Ogletree, Jr., launched the Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race and Justice at Harvard Law School to honor and continue Houston’s unfinished work to combat discrimination and secure equal rights and opportunity, with a particular emphasis on education.

“Without education,” Houston wrote, “there is no hope for our people, and without hope, our future is lost.”

Sources

Robert L. Carter et al., “In Tribute: Charles Hamilton Houston,” Harvard Law Review 111, no. 8 (1998): 2149–2179.

“Charles Hamilton Houston,” NAACP, accessed April 24, 2022, www.naacp.org/find-resources/history-explained/civil-rights-leaders/charles-hamilton-houston.