Intellectual Leadership: Harvard, Slavery, and Its Legacies before and after the Civil War

Context: A Nation Torn by Slavery and a Rising University

Well after slavery ended in Massachusetts in 1783, during the antebellum era and even after the 13th Amendment to the US Constitution conferred emancipation nationwide, in 1865, vestiges—or legacies—of the system lingered. Legacies of slavery such as exclusion, segregation, and discrimination against Blacks in employment, voting, housing, healthcare, public accommodations, criminal punishment, and education, among other areas, persisted in the South as well as the North well into the 20th century.Go to footnote 323 detail And the hardening of racial categories, advanced by race scientists at Harvard and elsewhere, provided intellectual justification for continued subjugation.

Notwithstanding the Commonwealth’s Revolutionary War heritage as birthplace of the colonists’ struggle for liberty, its celebrated antislavery activists, and its many brave Union veterans of the Civil War,Go to footnote 324 detail racial inequality flourished in Massachusetts—and at Harvard—as Blacks struggled for equal opportunity and full citizenship.Go to footnote 325 detail

The decades after the Civil War, during the period of Reconstruction when debates raged about whether and how to support the Black American quest for equality, are especially germane to understanding legacies of slavery in American institutions of higher education. The US Constitution changed, reflecting the nation’s formal break with slavery and commitment to equal citizenship rights regardless of race. The 14th Amendment to the US Constitution, conferring equal protection and due process of law, and the 15th Amendment, prohibiting discrimination against males in voting, were enacted and ratified.Go to footnote 326 detail Within this context, reformers conceived policies and social supports to uplift the formerly enslaved and their descendants. But it fell to the nation’s institutions, its leadership, and its people to safeguard—or not—citizens’ rights and implement these policies.Go to footnote 327 detail

Around the same time, Harvard itself aspired to transform: it sought to enlarge its infrastructure, expand its student body, and recruit new faculty. Samuel Eliot Morison, a noted historian of the University, explained that during the period from 1869 into the 20th century, the University resolved “to expand with the country.”Go to footnote 328 detail Harvard’s leaders, particularly Presidents Charles William Eliot and Abbott Lawrence Lowell, argued that Harvard should become a “true” national university that would serve as a “unifying influence.” They viewed the recruitment of students from “varied” backgrounds and a “large area” of the country as a linchpin of these ambitions.Go to footnote 330 detail

Hence, two developments critical to understanding this moment of promise and peril occurred at once: The fate of African Americans hung in the balance. And Harvard, already well known, sought to grow, evolve, and build a yet greater national reputation. In the end, the University proved unwilling to participate in efforts to promote the welfare of African Americans as it pursued national prominence, whether for the sake of political expediency, because many of its leaders subscribed to the concept of inherent differences among races, or—most likely—a combination of both.

Harvard and Abolitionism

Even as the majority at Harvard accommodated or advanced the era’s racial oppression, or tried to protect and promote Harvard’s growing reputation as a national institution by keeping it out of the fray, a small but important minority of Harvard faculty, students, and alumni—before and after the Civil War—rejected prevailing social norms and were vocal and active advocates for abolition. These Harvard affiliates spoke out against slavery and racial discrimination, and this counterhistory of resistance is also an important element of the story of Harvard’s entanglements with slavery.

In the decades leading up to the Civil War, the social and political climate at Harvard largely reflected that of the nation. Northern abolitionists advocated for the end of slavery in the United States; many Southerners in the Harvard community defended slavery, and moderates tried to chart a path between the two that might preserve the union. Harvard administrators, faculty, staff, and students were vocal participants on all sides of the ongoing national debates. Yet some of the most prominent voices drowned out and sought to suppress antislavery sentiment.

Harvard Affiliates and Abolitionist Organizations in Massachusetts

Notwithstanding pressure to stay away from public abolitionist activities, a review of published lists of supporters of several Massachusetts organizations illustrates the involvement of members of the Harvard community in advocating the abolition of slavery and the protection of the rights of African Americans.

In May of 1836, for example, a group of Cambridge residents, local politicians, and Harvard faculty came together to form the Cambridge Anti-Slavery Society. In addition to Charles Follen and Henry Ware Jr., both of whom are discussed below, the original signers of the group’s constitution included two-time acting University President Henry Ware Sr. (1810 and 1828–1829; faculty, 1805–1845), the retired faculty member and former University librarian Sidney Willard (librarian, 1800–1805; faculty, 1807–1831), and seven additional alumni of the University. In all, 11 of the 23 original members—nearly half—were Harvard affiliates.Go to footnote 331 detail

Almost 10 years later, the Boston-based abolitionist newspaper The Liberator published a list of votes for and against two resolutions passed at that year’s New England Anti-Slavery Convention, declaring it “the great fault of the United States Constitution” that it allowed slaveholders to “control the policy and character of the nation” and calling on abolitionists to “agitate for a dissolution of the Union.”Go to footnote 332 detail The diverse group of 250 men and women, both Black and white, who voted on these resolutions included the Harvard graduates and prominent abolitionists Wendell Phillips (AB 1831; LLB 1834) and Edmund Quincy (AB 1827; overseer, 1875–1877)—the latter of whom was the son of then–University President Josiah Quincy. The rolls also included the recording secretary of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society, Henry Willard Williams (MD 1849),Go to footnote 333 detail who would go on to become a faculty member at the Medical School, serving as the first chair of the Department of Ophthalmology, and the benefactor and namesake of the Henry Willard Williams Professorship in Ophthalmology at Harvard Medical School.Go to footnote 334 detail

Perhaps most striking is the prevalence of Harvard affiliates among the active members of the Committee of Vigilance of Boston, often referred to as the Boston Vigilance Committee, which worked through legal channels and in partnership with organizations like the Underground Railroad to assist self-emancipated enslaved people to evade capture after passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850. While membership of the organization was necessarily guarded, in an 1880 memoir, one-fifth of 209 members listed as active between 1850 and 1860 were Harvard graduates. This included the future Harvard faculty members Henry Ingersoll Bowditch (Jackson Professor of Clinical Medicine, 1859–1867), Richard Henry Dana Jr. (lecturer at Harvard Law School, 1866–1868; overseer, 1865–1877), and James Russell Lowell (Smith Professor of the French and Spanish Languages and Literatures and Professor of Belles Lettres, 1855–1886; emeritus, 1886–1891; overseer, 1887–1891).Go to footnote 335 detail

Joshua Bowen Smith: Black Abolitionist on Campus

One of the most active abolitionists in Harvard’s employ in the period before the Civil War was a free Black man, although his abolitionist work was independent of the University. Joshua Bowen Smith founded a catering business in Boston in 1849 and for 25 years served gatherings of the local elite. Smith contracted with Harvard to prepare daily meals for students as well as more lavish fare at major celebrations like Commencement;Go to footnote 336 detail he provided services that had earlier fallen to the stewards and, in some cases, their enslaved workers.Go to footnote 337 detail Smith invested the proceeds of his work for Harvard and other Boston-area institutions in abolitionist causes.Go to footnote 338 detail He was directly involved in antislavery efforts as a member of the Underground RailroadGo to footnote 339 detail and as a member of the executive committee of the Boston Vigilance Committee.Go to footnote 340 detail Smith was also a cofounder of the New England Freedom Association, which provided basic necessities and legal defense to escaped enslaved people. He sometimes employed waiters and cooks connected to the association, and it is possible that some of the escapees Smith helped evade capture may have prepared food or waited tables for Harvard’s students and faculty.Go to footnote 341 detail

Charles Follen, Henry Ware, and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow: Abolitionist Faculty Members

Members of the Harvard faculty who worked to advance the abolitionist cause often faced particularly significant resistance from the University. In the 1830s, two abolitionist faculty members—Charles Follen (1825–1835), a professor of German, and Henry Ware Jr. (1829–1842; overseer, 1820–1830), a member of the faculty at the Divinity School—faced pressure to curtail their involvement with the newly founded Cambridge Anti-Slavery Society.Go to footnote 342 detail Follen believed he lost his full-time teaching role at the University because of his abolitionist activities; he resigned rather than accept a demotion to part-time instructor.Go to footnote 343 detail Ware, according to an 1846 biography written by his brother, was warned by friends and colleagues to limit his involvement with the society, and he eventually resigned from the organization.Go to footnote 344 detail

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Smith Professor of the French and Spanish Languages and Literatures and Belles Lettres (1836–1854), straddled the social and professional networks that divided abolitionists and supporters of slavery.

Throughout his life, Longfellow maintained friendships with prominent abolitionists, including Richard Henry Dana Jr., James Russell Lowell, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Harriet Beecher Stowe.Go to footnote 345 detail The firebrand Free Soil Party member and US Senator Charles Sumner (AB 1830; LLB 1834), whom Longfellow supported actively—if mostly in private correspondence—was among his closest friends.Go to footnote 346 detail Yet so too was Louis Agassiz, the proponent of race science.Go to footnote 347 detail

Longfellow’s most public stand against slavery came in 1842, when he published the volume Poems on Slavery, which described the horrors of slavery in painful detail and was popular among white audiences as well as Black.Go to footnote 348 detail For the most part, however, he expressed his antislavery views privately—in his correspondence and his journals.Go to footnote 349 detail Believing that slavery was “an unrighteous institution,”Go to footnote 350 detail Longfellow donated to abolitionist causes, too: particularly after the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act, his records show numerous payments in support of escaped slaves, their families, and those who harbored them. He also supported Black schools and churches in the United States, Canada, and Haiti and gave money to purchase enslaved people’s freedom.Go to footnote 351 detail

Longfellow wrote to Sumner that the goal of emancipation should be to place “the black man … upon the same footing as the white.”Go to footnote 352 detail And he did so in his home, welcoming members of the Black community as guests. In 1846, the escaped slave Josiah Henson—widely known to be the model for Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom—called on Longfellow in Cambridge in search of funds to support a school; Longfellow donated that day and would do so again many times over the next 30 years.Go to footnote 353 detail At the height of the conflict over the Fugitive Slave Act, Longfellow hosted Lunsford Lane, an escaped slave and abolitionist from North Carolina, and Darby Vassall, the early advocate for free Black rights who was born in bondage at Longfellow’s very home in 1769, when it belonged to John Vassall.Go to footnote 354 detail

John Gorham Palfrey: Abolitionist Dean

The experience of Professor and Divinity School Dean John Gorham Palfrey (faculty, 1830–1839; overseer, 1828–1831, 1852–1855) illustrates both the presence of active abolitionists in the Harvard community and some of the challenges they faced.

Palfrey grew up in Boston, attended Phillips Exeter Academy alongside future Harvard President Jared Sparks (1849–1853), and graduated with a master’s degree from Harvard Divinity School in 1818. After more than a decade as the minister of a multiracial congregation at Boston’s Brattle Street Church, he returned to Harvard in 1830 as professor of biblical literature and dean of the Divinity School. While one biographer describes the “timidity” of Palfrey’s abolitionism during these years—Palfrey joined the nascent Cambridge Anti-Slavery Society in the 1830s but quickly backed away in the face of “public opinion”—Palfrey became more vocal after 1838.Go to footnote 355 detail

In that year, Palfrey received word from his brothers in Louisiana that his father’s health was declining, raising the prospect that Palfrey soon might inherit enslaved people from his father’s plantation. He immediately began to investigate how he might legally free any enslaved people who passed to him.Go to footnote 356 detail At the same time, Palfrey faced pressure from Harvard President Josiah Quincy to postpone an abolitionist public debate, organized by Divinity School students, as Quincy feared a disturbance to campus life. In correspondence, Quincy urged Palfrey to reconsider the event, which Quincy deemed unsuitable for “a seminary of learning, composed of young men, from every quarter of the country; among whom are many whose prejudices, passions, and interests are deeply implicated and affected by these depulsions and who feel very naturally and strongly on the subject.”Go to footnote 357 detail When Palfrey opted not to postpone the debate, Quincy wrote again, objecting to the fact that students from across Harvard had been invited to the event and stating his intention to seek the “advice and action” of the Corporation.Go to footnote 358 detail Less than two months later—although not in time to prevent the debate—the Corporation adopted a resolution that forbade anyone other than University faculty or staff members “to teach, lecture or preach, or deliver any oration or discourse in any of the schools belonging to the University, or in any Society connected with either of them” without permission.Go to footnote 359 detail Palfrey resigned from Harvard shortly thereafter, in 1839, and entered politics.

In the ensuing years, Palfrey was elected as the Whig candidate and an abolitionist to the Massachusetts state legislature (1842–1843); appointed secretary of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts (1844–1847); and elected to the United States House of Representatives (1847–1849).Go to footnote 360 detail

Palfrey’s father died in 1843 and, true to his earlier intentions and despite the opposition of his brothers, he hired an agent in New Orleans to seek the bulk of his inheritance in human property. Palfrey then freed the older people among the enslaved he inherited and paid to transport the others—16 men, women, and children under the age of 30 who could not legally be manumitted under Louisiana’s laws—to the NortheastGo to footnote 361 detail, where he found paid work for them in homes across Massachusetts and New York.Go to footnote 362 detail

In 1848 Palfrey, newly affiliated with the abolitionist Free Soil Party, ran for reelection to the US House of Representatives. He lost but remained active in Massachusetts politics, where debate over slavery heated up following the enactment of the Compromise of 1850 and a ruling of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court that the Fugitive Slave Act, a key element of the compromise, must be enforced in the state.Go to footnote 363 detail These developments helped turn public opinion in the Commonwealth against slavery, and this period marks perhaps the moment of starkest disconnect between Harvard, with its national ambitions, and New England over the question of abolition.Go to footnote 364 detail

Around this same time, Palfrey’s activism again drew the notice of the Harvard community.Go to footnote 365 detail In March 1850, his longtime friend, Harvard President Jared Sparks (faculty, 1838–1849; president, 1849–1853), made a personal call: Sparks, a moderate who opposed slavery but favored the removal of former slaves from the United States, told Palfrey that his activities on behalf of the Free Soil Party were harming Harvard’s reputation—this despite the fact that Palfrey had not worked at the University for more than a decade. Palfrey was outraged by Sparks’s request that he moderate his political activities.Go to footnote 366 detail

Sparks’s request appears to have been driven by concerns about how the abolitionist activities of Harvard affiliates like Palfrey were influencing national public opinion of the University. Later in 1850, Sparks received a letter from Caleb Cushing, a Harvard graduate and former US representative from Massachusetts, complaining that “abolitionism and political Free Soilers” were “sheltered and nurtured under the broad wings of the university.”Go to footnote 367 detail This pushback occurred around the same time that Harvard Medical School admitted the Black students Daniel Laing Jr., Isaac H. Snowden, and Martin Robison Delany, only to rescind their admission in the face of protests from white students and families—many of them Southern.Go to footnote 368 detail (This incident is discussed in greater detail below.) Moreover, in 1851, in response to questions from the Massachusetts legislature—which still provided funding to Harvard in this period—Sparks explained low enrollment by noting that Southerners had been hard to recruit in recent years. Concerns about the recruitment and retention of Southern students were certainly on his and other administrators’ minds.Go to footnote 369 detail

Following Palfrey’s failed 1851 run for Governor of MassachusettsGo to footnote 370 detail and Sparks’s 1852 decision to step down as Harvard president and leave the University, Ephraim Peabody, a Harvard Divinity School graduate and pastor of Boston’s King’s Chapel, wrote to Palfrey to inquire whether he would be interested in being nominated for Sparks’s soon-to-be vacant professorship. Peabody, while not an officer of the University, was well connected with prominent Harvard affiliates, several of whom were active members of his parish.Go to footnote 371 detail The offer came with a caveat: Peabody warned Palfrey that “an active part in the politics of the day beyond what is incumbent on every private citizen, would be thought by the Corporation & by the Public incompatible with an Office in the College.”Go to footnote 372 detail

Palfrey wrote back expressing his interest in the position, not least because he needed a means of supporting his family. He also acknowledged that the University leadership would expect him to show restraint in politics, but he did not commit to remaining on the sidelines.Go to footnote 373 detail There is no record of any further correspondence on this subject, but Palfrey did not succeed Sparks as the McLean Professor of Ancient and Modern History.

The next year, Sparks himself sought another prominent University position for Palfrey, suggesting to members of the Corporation that Palfrey be considered for the role of treasurer upon the incumbent’s retirement. Palfrey did not receive that position either, and in this case, the reasons are on record. Fellow Charles G. Loring (AB 1812; fellow, 1838–1857) advised against nominating Palfrey because of his politics, despite Loring’s conviction that Palfrey would be an excellent treasurer:

The only doubt arises from his peculiar position as a very prominent leader of a political party, against which such inveterate lividity exists among a large portion of the influential members of society at the North, in the Middle States–, & which is unanimously felt at the South.– This would weigh nothing with me, if the appointment were to a private office, in which the public has no interest, nor any right to interfere. But the College is eminently public, & ought to be managed as a national institution–, & it becomes therefore a grave question, how far any office should be filled by a person, who is obnoxious to the [illegible], or ill will of a section of the nation, or any large portion of the people.Go to footnote 374 detail

Loring went on to imply that he was supported in this view by “the Ch. J.”—Lemuel Shaw, then chief justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court and another Harvard fellow.Go to footnote 375 detail While Loring and Shaw were personally opposed to slavery, they took a moderate line in hopes of protecting Harvard as a “national” university.

The events of the 1850s eventually drove Harvard, like every other national institution, to take a stand. In the end, abolitionists were partly vindicated, while political moderates fell out of favor: In 1855, just two years after rejecting Palfrey as treasurer, the Corporation declined to grant an honorary degree to the former treasurer Samuel Atkins Eliot, who had voted for the Fugitive Slave Act while in Congress.Go to footnote 376 detail In 1859, Harvard granted honorary degrees to the abolitionists Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Charles Sumner.Go to footnote 377 detail From 1861 to 1865, Harvard’s national stature and the internal divisions that came with it were reflected in the service of Harvard men in the Civil War: 1,358 Harvard men enlisted for the Union, and 136 of them died; another 304 enlisted for the Confederacy, of whom 70 lost their lives.Go to footnote 378 detail Palfrey ended his career not at Harvard but in politics, appointed the postmaster of Boston in 1861 by President Abraham Lincoln.Go to footnote 379 detail

Legacies of Slavery in Scholarship: Race Science

By 1850, Harvard Medical School had become a focal point of scientific theories and practices rooted in racial hierarchy, racial exclusion, and discrimination at the University. That same year, as we have seen, the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, requiring the return of enslaved people to their owners even if slaves had escaped to free states, turned more white Northerners against slavery and its cruelties. Yet support for antislavery efforts remained anemic at Harvard, even amid the rise of abolitionist sentiment in the Commonwealth. Indeed, at Harvard Medical School, the forces of conformity with the racial status quo, aided by Harvard presidents and leading Harvard faculty members, prevailed against those who dissented.

Harvard Medical School Dean Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. was at the helm during an 1850 controversy over the abortive admission of the Medical School’s first three Black students, and his views on race help contextualize this episode.Go to footnote 740 detail They also shed light on the group of hugely influential Harvard faculty members whose work in so-called “race science”—the study of racial differences that emphasized the superiority of whites and inferiority of African peoples—would legitimize racist views among generations of scientists, medical researchers, and indeed political leaders. An alumnus of Harvard College (1829) and Harvard Medical School (1836), Holmes was a prominent anatomist and a prolific poet when he became dean in 1847.Go to footnote 380 detail Among his friends and colleagues were the race science proponents Jeffries Wyman and Louis Agassiz, also hired in 1847 as the University worked to grow its ranks of prominent scientists in the 19th century.Go to footnote 381 detail Holmes, like many scientists of the time, held similar views to Wyman and Agassiz. Holmes at times promoted the idea of innate differences in moral character, health, and intelligence among races.Go to footnote 382 detail He also defined “the Brahmin caste of New England” to describe himself and his peers, distinguishing between “the common country-boy, whose race has been bred to bodily labor” and the “races of scholars,” like himself, who “take to [their] books as a pointer or a setter to his field-work.”Go to footnote 383 detail In an Atlantic Monthly essay published in April 1875, Holmes cited, among others, Francis Galton, an English scientist known as the father of eugenics,Go to footnote 384 detail asserting that “in most cases, crime can be shown to run in the blood.”Go to footnote 385 detail

Such ideas were perhaps related to Holmes’s engagement with anatomical racial difference.Go to footnote 386 detail During the 19th century, Harvard had begun to amass human anatomical specimens, some of which were the bodies of enslaved people. Holmes was among the scientists who donated human remains to the Warren Anatomical Museum, including a skull (apparently from Africa): “The obliteration of the cranial sutures that characterize the African is finely shown,” he explained.Go to footnote 387 detail Such racialized collections would, in the hands of the University’s prominent medical and scientific authorities, become central to the promotion of race science at Harvard and many American institutions, as discussed in greater detail below.

Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. and Black Students at Harvard Medical School

On November 2, 1850, Holmes met with Medical School faculty members to consider an inquiry about the admission of two Black students, Daniel Laing Jr. and Isaac H. Snowden, who were well qualified and had the support of members of the American Colonization Society (ACS), which advocated for the removal of free Black Americans to Africa.Go to footnote 388 detail The day before, Abraham R. Thompson and Joseph Tracy, the former a Medical School alumnus (1826) and both members of the ACS Board of Directors, had written to the Medical School faculty endorsing Laing and Snowden as “two young men of colour, pursuing medical studies … for the purpose of practicing in the Republic of Liberia in Africa, where their services are greatly needed.”Go to footnote 389 detail The faculty voted to admit.Go to footnote 390 detail

Not long thereafter, a third Black applicant sought admission on his own initiative. Martin Robison Delany, who was already a prominent abolitionist, writer, and speaker, visited Dean Holmes in person. Although Delany was not supported by the ACS like Laing and Snowden, he too had the prerequisite medical training, and 17 white doctors from Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, had endorsed his application. Holmes extended an offer of admission.Go to footnote 391 detail

Laing, Snowden, and Delany would, however, have a tumultuous and extremely brief tenure at the Medical School. Their reversal of fortune started when 10 white students signed a petition asking to be “informed whether colored persons [were] to be admitted as students at another course of lectures.”Go to footnote 392 detail Other resolutions followed. On December 10, 1850, some 60 of Laing, Snowden, and Delany’s 116 white colleagues met and, by a slim majority, voted to endorse a resolution stating that the admission of Black students would degrade the quality of their degrees. The signers refused to “be identified as fellow-students, with blacks; whose company we would not keep in the streets, and whose society as associates we would not tolerate in our houses.”Go to footnote 393 detail

The opposition to the Black students was not universal. Another group of students drafted a competing resolution on December 11, cautioning the University against rescinding admission to the three Black students: “As students of science … they would feel it a far greater evil, if, in the present state of public feeling, a medical college in Boston could refuse to this unfortunate class any privileges of education, which it is in the power of the profession to bestow.”Go to footnote 394 detail

Nevertheless, Holmes and the faculty determined to exclude the three Black students, deeming them irritants and distractions to the educational environment. In a letter to the sponsors of Laing and Snowden, Holmes and the faculty described this episode as a failed “experiment,” which had proved that “the intermixing of different races, on a footing of equality and personal proximity during the course of Lectures, is distasteful to a large portion of the class, and injurious to the interests of the School.”Go to footnote 395 detail

Race Scientists: Louis Agassiz, John Collins Warren, and Jeffries Wyman

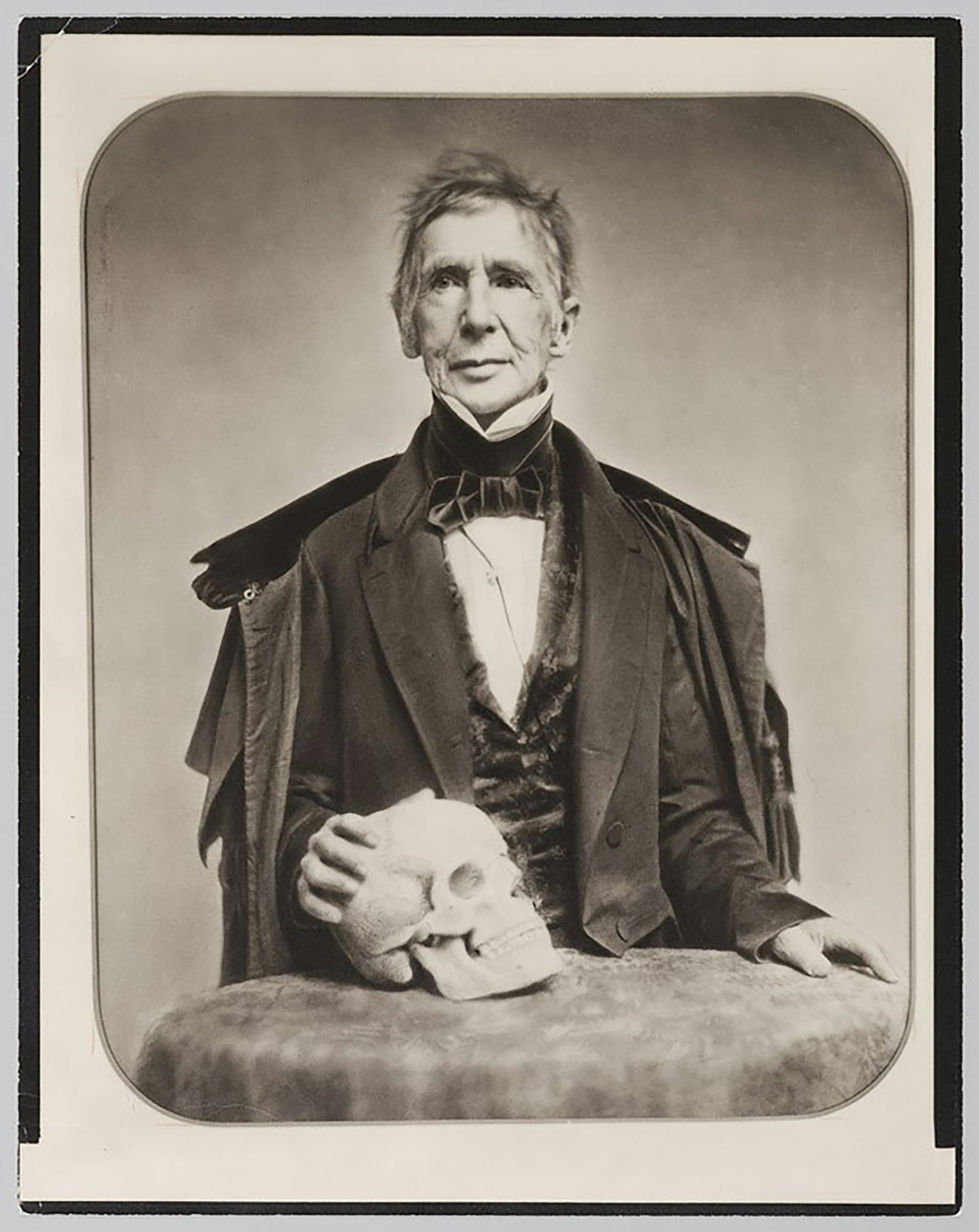

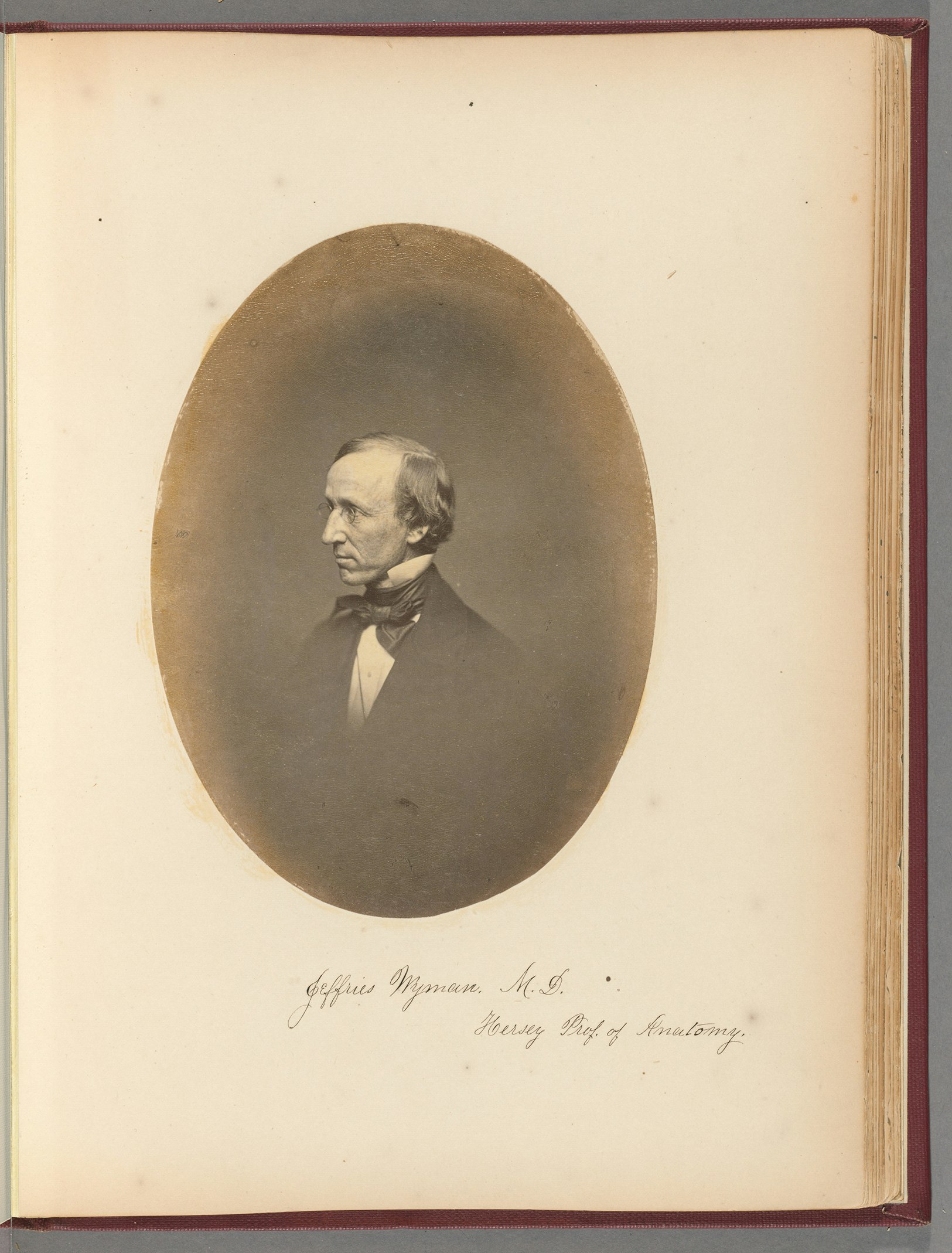

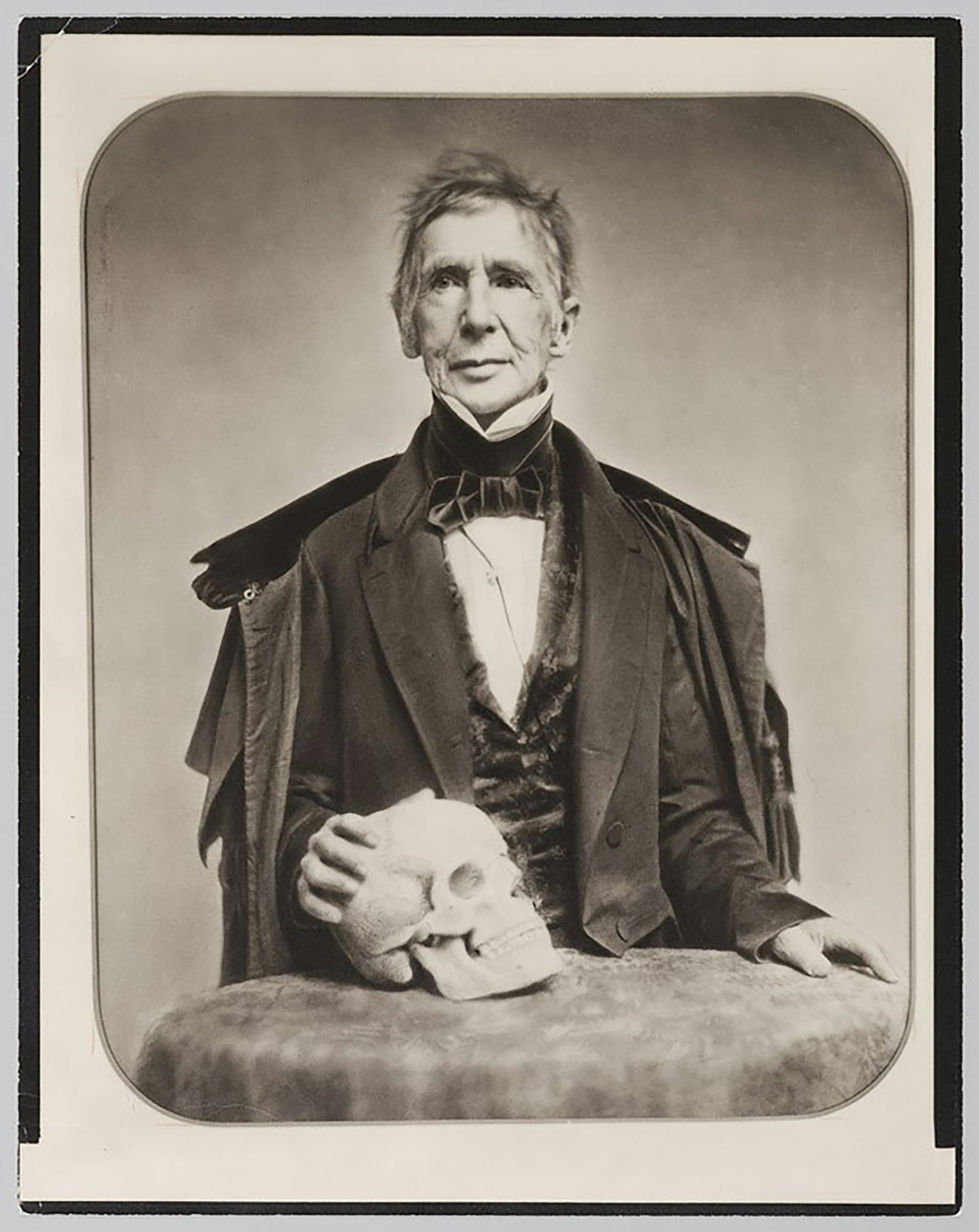

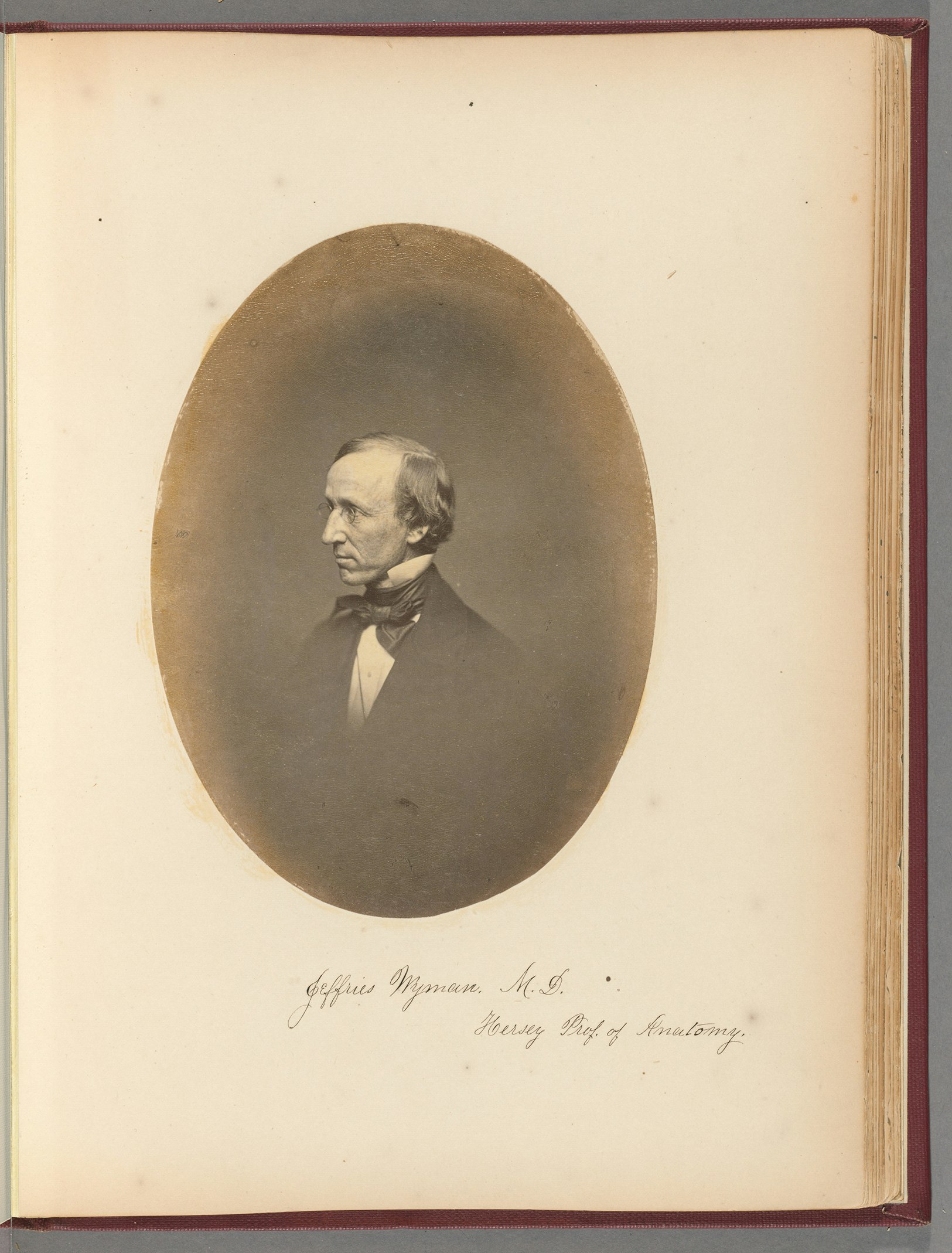

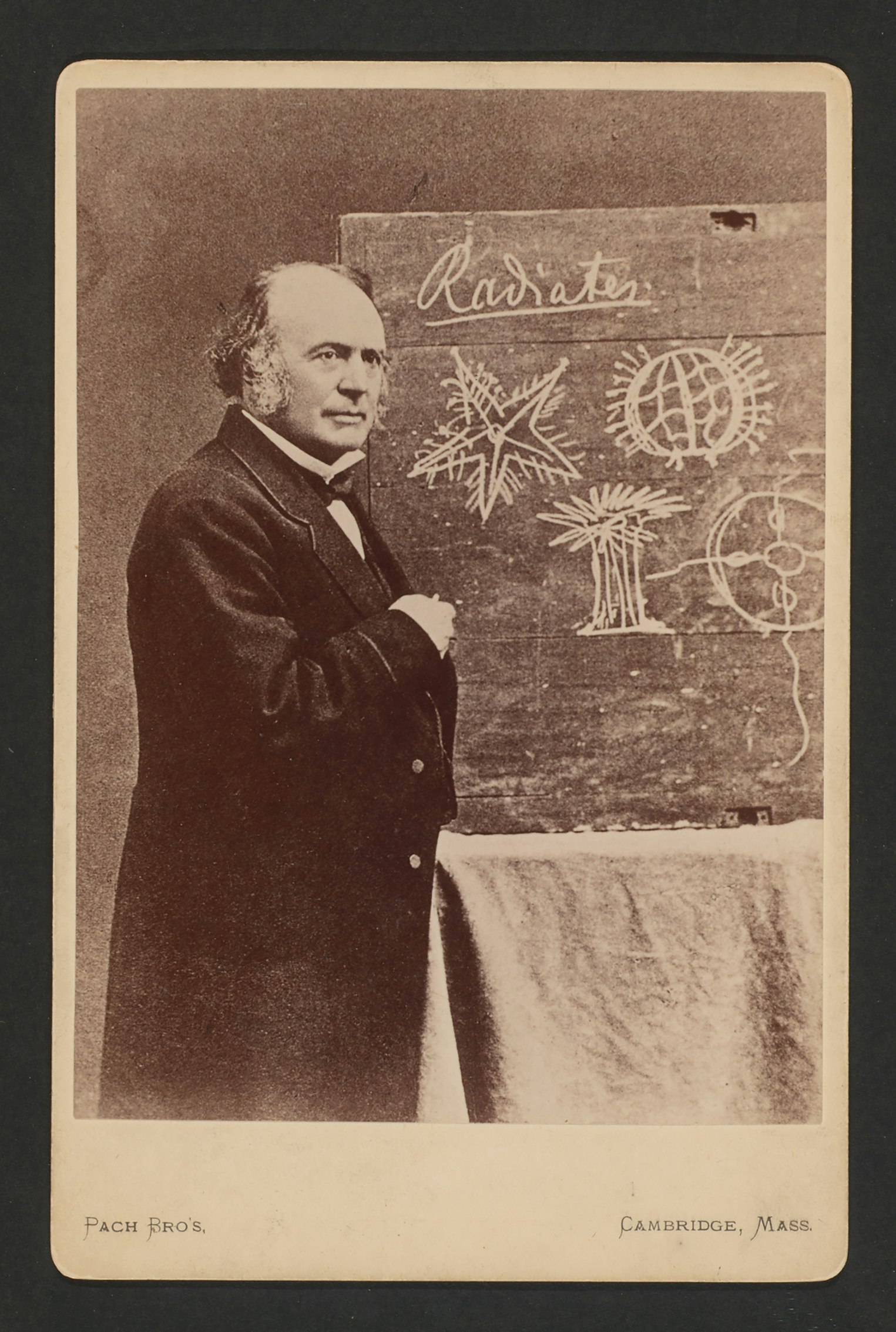

This episode took place in the context of the growth of race science at Harvard, which provided an intellectual framework to justify the exclusion and marginalization of Blacks that would endure into the 20th century. Along with Holmes, those engaging with racial difference at Harvard included John Collins Warren (AB 1797; dean, 1816–1819; faculty, 1809–1856), the son of one of the Medical School’s cofounders and himself the first dean of the faculty of medicine, and Holmes’s contemporaries Jeffries Wyman (faculty, 1838–1840 and 1847–1874) and Louis Agassiz (hon. 1848; faculty, 1847–1873). No one was as influential in this area as the renowned Swiss-born scientist Agassiz, yet each of these men—Warren, Wyman, and Agassiz—left powerful legacies on Harvard’s campus and in the wider world.

Agassiz and Wyman both joined Harvard at a time of institution-building, Agassiz at the new Lawrence Scientific School and Wyman, like Holmes, at the Medical School.Go to footnote 396 detail Wyman succeeded Warren as a professor of anatomy, but Warren remained active in the University until his death in 1856. These three men, as colleagues and collaborators, were instrumental in the creation of major Harvard institutions.

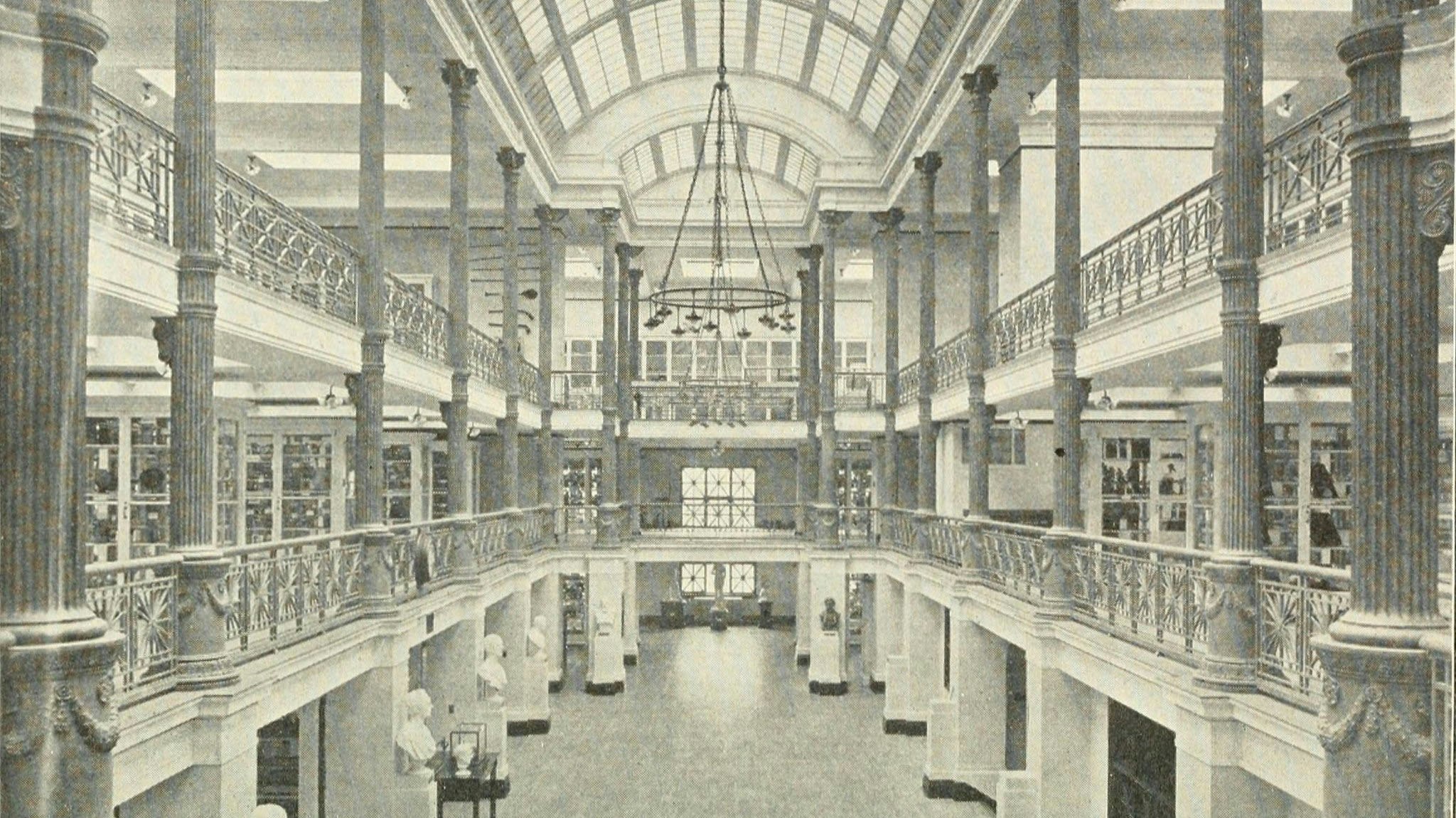

The Warren Anatomical Museum, now housed within Harvard Medical School’s Countway Library, was established when Warren donated his and his father’s vast collections of “pathological and other specimens” to Harvard, including human skulls and “phrenological” casts.Go to footnote 397 detail Wyman led the creation of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, where he served as inaugural curator. And Agassiz established and served as the first curator of the Museum of Comparative Zoology.Go to footnote 398 detail

The Agassiz name remains visible across Harvard’s campus and the City of Cambridge. Louis, who served as professor of zoology and geology from 1847 to 1873 and as curator of the Museum of Comparative Zoology from its founding in 1862 until 1873,Go to footnote 399 detail is the most well-known member of the Agassiz family. Yet the memorials that remain are generally named for his wife, Elizabeth Cary Agassiz (for instance a professorship, a gate in Radcliffe Yard, and Elizabeth Cary Agassiz House, home of the Harvard College Admissions Visitor Center), or for his son, Alexander Agassiz (namesake of Harvard professorships).

Elizabeth is credited as coauthor of A Journey in Brazil (1868), a travelogue about their yearlong scientific expedition in the country, discussed below.Go to footnote 400 detail She also left her own powerful mark at Harvard: in 1879, she was among a group of reformers who founded the Harvard Annex, where women could receive instruction from Harvard faculty. The Annex was soon incorporated as the Society for the Collegiate Instruction of Women, and in 1894, it was chartered as Radcliffe College. Elizabeth served as the first president of Radcliffe College and was a pioneering leader in the history of women’s education.Go to footnote 401 detail Alexander, an engineer and investor in copper mining as well as a scholar of natural history, also worked closely with his father. He handled much of Louis’s correspondence in the final years of his life and succeeded Louis as curator of the Museum of Comparative Zoology in 1874.Go to footnote 402 detail Alexander donated substantial sums to several organizations in the final years of his life, including more than $200,000 to the museum to support research, publications, and the professorships that still bear his name.Go to footnote 403 detail

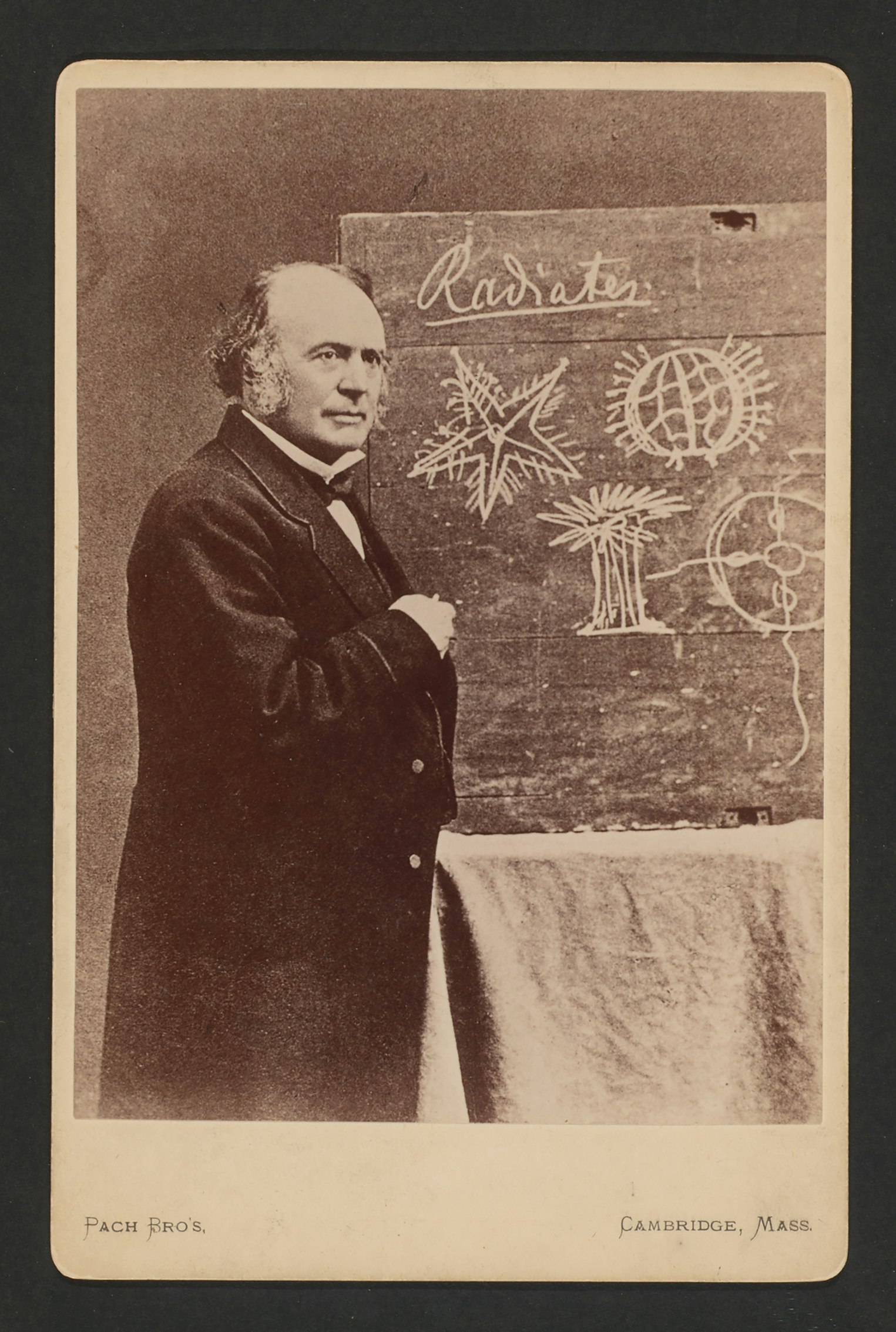

Agassiz’s Early Career and the Zealy Daguerreotypes

Louis Agassiz’s journey to Harvard began when he was invited to deliver the Lowell Institute’s Lowell Lectures.Go to footnote 404 detail While the institute was not affiliated with Harvard, it was a forum that attracted many esteemed Harvard affiliates as lecturers and guests. Agassiz’s 1845 invitation came on the recommendation of the German naturalist Alexander von Humboldt, who was able to secure funding for Agassiz’s Atlantic crossing through his position as an advisor to the king of Prussia.Go to footnote 405 detail Agassiz was by then a prominent naturalist, known in Europe’s scientific circles for his work on glaciation and the classification of ancient fish species.Go to footnote 406 detail In this work, he was part of a movement toward classifying flora and fauna according to geographic origin, building upon Carl Linnaeus’s universal system of classification.Go to footnote 407 detail Naturalists of the era were known for their splendid depictions of nature and often went on scientific expeditions in the Americas to collect specimens for their research. Their preoccupation with nature also extended to the classification of humans “into a single natural hierarchy of difference and similarity,” organized under the rubric of race.Go to footnote 408 detail

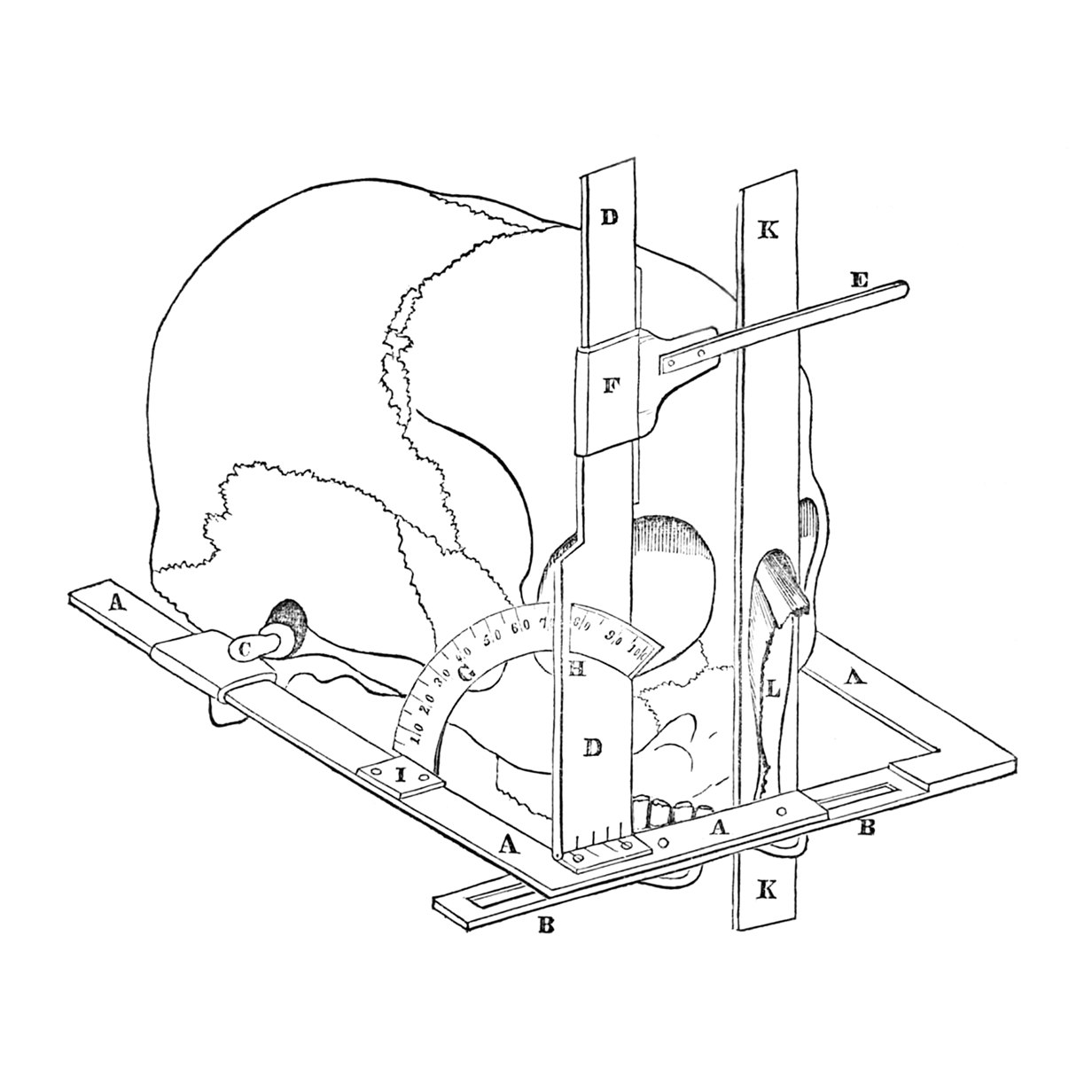

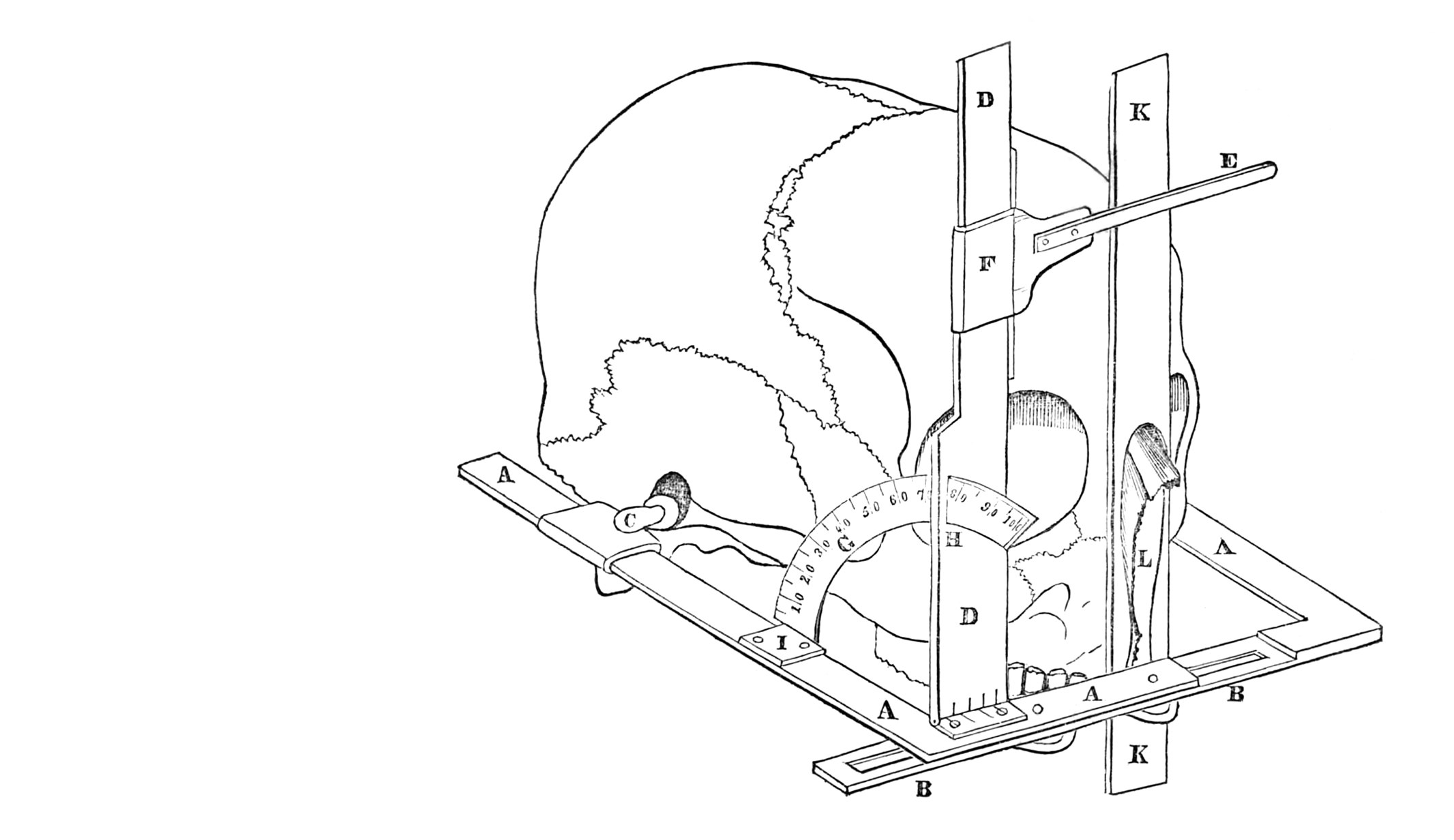

The field of anthropology emerged in this context to study diversity among human groups as a function of visible racial difference.Go to footnote 409 detail Medical scientists contributed to the field’s growth by investigating relationships among racial typology, geography, and disease. Phrenology, which related the shape and size of the cranium to intellectual and moral faculties, became a popular racial scientific field; craniometry, the measurement and dissection of human skulls, was its primary method. By the 19th century, race science had become a global enterprise,Go to footnote 410 detail and Agassiz was fully immersed when he arrived in the United States in the fall of 1846.

Among the first things Agassiz did in America was to view the prominent anatomist Samuel George Morton’s skull collection in Philadelphia,Go to footnote 411 detail an early stop on his tour of the scientific community in the United States, which warmly embraced him.Go to footnote 412 detail Agassiz spent “four hours in contemplation” of the skulls of Native Americans and received a personal copy of Morton’s Crania Americana, inscribed by the author. In a letter to his mother, Agassiz wrote that Morton’s “collection alone merits a trip to the United States.”Go to footnote 413 detail He also reflected on his first encounter with African Americans:Go to footnote 414 detail “It is impossible for me to repress the feeling that they are not the same blood as us.”Go to footnote 415 detail

At this time, the United States was on the verge of establishing its own scientific institutions and schools of thought independent from those of Europe. Polygenism—which proposed not only a hierarchy of races but also separate creations of different races—was “an important agent in this transformation” because it was “of largely American origin” yet acquired authority from European scientists who had long pursued scientific theories of racial difference themselves.Go to footnote 416 detail Agassiz understood the importance of this moment in the nation’s intellectual life and saw an opportunity. Some two years later, now a member of the Harvard faculty and building a celebrity status matched by few other scientists, he declared to the Boston Society of Natural History that American scientists “had been obliged to look up to Europe as our leader and guide in this pursuit,” but “a short period of persevering labor … would place America in the position hitherto occupied by the Old World.”Go to footnote 417 detail

Agassiz first formally articulated his embrace of polygenism at an 1850 meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) in Charleston, South Carolina.Go to footnote 418 detail In an essay published soon thereafter, he set out to disprove the “prevailing opinion, which ascribes to all living beings upon earth one common centre of origin, from which it is supposed they, in the course of time, spread over wider and wider areas, till they finally came into their present distribution.”Go to footnote 419 detail His primary objective was “to show that there is no such statement in the book of Genesis: that this doctrine … is of very modern invention, and that it can be traced back for scarcely more than a century in the records of our science.”Go to footnote 420 detail In another essay, he concluded that Blacks were at the bottom of a racial hierarchy ordained in nature and contended that “there has never been a regulated society of black men developed” in Africa, suggesting a “peculiar apathy … to the advantages afforded by civilized society.”Go to footnote 421 detail

Such views were controversial even then. The first half of the 19th century represented a period of hardening of race as a scientific concept in the United States, at the height of debate over “monogenesis” versus “polygenesis,” or the single versus separate origins of races.Go to footnote 422 detail Monogenists, who believed in a single human creation, immediately criticized Agassiz’s arguments. Writing to her then fiancé, Elizabeth Cary noted the opposition building to his ideas: “Some of the Church people are out upon you in the papers, for your disrespect of Adam as the common father of mankind.”Go to footnote 423 detail Congress was also, at this time, debating the Fugitive Slave Act, the passage of which would galvanize antislavery sentiment in New England.Go to footnote 424 detail Agassiz flatly denied that his research had bearing on the fraught political question of slavery,Go to footnote 425 detail although he asserted that it was “mock-philanthropy and mock-philosophy to assume that all races have the same abilities, enjoy the same powers, and show the same natural dispositions, and that in consequence of this equality they are entitled to the same position in human society.”Go to footnote 426 detail

Agassiz was celebrated in the South, where he was invited to the homes of prominent slaveholders and gave iterations of his 1850 AAAS lecture.Go to footnote 427 detail Some of these visits were arranged by a local paleontologist and physician who welcomed Agassiz to plantations in Columbia, South Carolina, to examine enslaved Africans as live research specimens. Following Agassiz’s examination, Joseph T. Zealy made daguerreotype images of seven men and women for Agassiz’s further study: Delia, Jack, Renty, Drana, Jem, Alfred, and Fassena.Go to footnote 428 detail In so doing, Zealy created what the New York Times described in 2020 as “some of history’s cruelest, most contentious images—the first photographs, it is believed, of enslaved human beings.”Go to footnote 429 detail

It was more than a century before historians retraced the identities and origins of the individuals represented in Agassiz’s daguerreotypes. We now know that Delia, Renty’s daughter, was an enslaved girl from Columbia, and that Jack was Drana’s father. Fassena, noted in the daguerreotype as a carpenter, was Mandingo, originally from modern southern Mali and Northern Guinea. They are each pictured nude or nearly so.Go to footnote 430 detail

Agassiz returned to the South in 1851–1852 with his new wife, Elizabeth, who would become his frequent collaborator. The collection of research specimens—including human specimens—remained his focus.Go to footnote 431 detail In an 1852 letter, he begged pardon for his delayed arrival at his next destination, explaining that he “found … an excellent opportunity of examining the negros, of which I must avail myself.”Go to footnote 432 detail

Agassiz’s wide-ranging specimen collections were a celebrated part of life and learning at Harvard. In an 1850 report to the overseers, University President Jared Sparks highlighted Agassiz’s, Wyman’s, and the University’s collections. Some of these were on display in Holden Chapel, used by the Medical School as a lecture hall and then assigned to the new Lawrence Scientific School, including a “curious collection of casts of skulls … which was purchased and presented to the University several years ago.”Go to footnote 433 detail

Wyman, Agassiz, and Sturmann

In September of 1860, “an extraordinary importation from South Africa” arrived in Boston—five human beings described as “a Fuigo, a Zulu, a Kaffir, a Bushman, and a Hottentot, all sons of the forests and the desert who have hitherto lived the life of savages.”Go to footnote 434 detail These living “specimens,” had been acquired by the owners of the Boston Aquarial and Zoological Gardens for public exhibition. The announcement promised a one-of-a-kind experience, “seeing these specimens of human nature in a savage condition just as they appear in their native forests and wilds”—including “monkey tricks.” Their names were given as Machiado, Macormo, Macuolo, Quaggu, and Sturmann.Go to footnote 435 detail

Advertisements described how the museum space was divided into two departments: the aquarial and the zoological.Go to footnote 436 detail The Africans were to be displayed alongside an assortment of “rare and beautiful animals and birds” including seals, kangaroos, and “Serpents.”Go to footnote 437 detail “[R]efined and intellectual” ticketholders were promised performances of savagery on a regular schedule:

They will appear through the day, CLAD IN THEIR NATIVE DRESSES OF SKINS, ORNAMENTED WITH BEADS, FEATHERS AND PORCUPINE QUILLS, and every evening will go through the WAR, LOVE and FESTIVE DANCES,—(armed with their SPEARS, CLUBS, SHELLS, AND OTHER WEAPONS OF WAR AND OF THE CHASE,) and will also SING the NATIONAL SONGS of their SEVERAL TRIBES.Go to footnote 438 detail

The museum’s owners created a scholarly veneer by commissioning a detailed pamphlet purporting to describe “the early life of each individual specimen of the nomadic tribes.”Go to footnote 439 detail And Agassiz lent his scientific authority to the proceedings, addressing an inaugural gala on October 4, 1860.Go to footnote 440 detail

Three months later, when the popular showman P. T. Barnum exhibited the Africans in New York City, public outcry over the questionable nature of their “importation” prompted him to print a statement from Agassiz in local newspapers. Agassiz “testified” that they were not enslaved but “were shipped with the knowledge and consent of the local authorities,” and that “nothing was done in securing them that would be objectionable either in a moral point of view or with reference to the laws of nations.”Go to footnote 441 detail He did not identify these “local authorities,” nor did he address the consent of Machiado, Macormo, Macuolo, Quaggu, and Sturmann themselves.

One of the five, Sturmann, took his own life on April 28, 1861, after more than six months on display.Go to footnote 442 detail The Boston Evening Transcript announced his death in a brief editorial:

The young Hottentot at the Aquarial Gardens, yesterday terminated his life by hanging. He was seventeen years of age and used to drive a wagon at Port Natal. For several days he was noticed to act strangely, and, just before the commission of the fatal act, conveyed from the room, where he and his four companions domesticated, nearly every moveable article, in accordance with the practice of all suicides among his people. The other Africans at the Gardens are deeply affected by the death of their companion.Go to footnote 443 detail

Regardless of their distress, Machiado, Macormo, Macuolo, and Quaggu were “again on exhibition” on April 30.Go to footnote 444 detail

Sturmann’s time as an object of study in the service of race science was only beginning: Wyman, who had met Sturmann while he was on display, dissected the teenager’s body at Harvard, ultimately publishing his observations in an 1865 issue of the journal the Anthropological Review.Go to footnote 445 detail He took extensive measurements and compared them to those of a chimpanzee, a gorilla, and two Europeans. In a protracted discussion of Sturmann’s pelvis, he noted that in some respects it came “nearer to that of the anthropoids [apes] than of the Caucasians”Go to footnote 446 detail but concluded it “belonged to the human family.”Go to footnote 447 detail

Ultimately, Sturmann’s remains were recorded in the catalog of the Warren Anatomical Museum:

Item # 3237 cast of the head of a native Hottentot. The boy was seventeen years old, had been on exhibition for several months in this city; and finally hung himself. His skeleton is in the Museum of Comparative Zoology, at Cambridge, 1861.”Go to footnote 448 detail

The casts of Sturmann’s head remain in Harvard’s collections.

Global Collecting and the Brazil Expedition

Over nearly three decades, Agassiz also engaged colleagues across the United States and around the world, especially in the Caribbean and Latin America, to collect and classify the natural world for what would become the Museum of Comparative Zoology.Go to footnote 449 detail He instructed his collectors—including patrons, friends, readers, and lecture audiences—to send him animals of all kinds from across New England, the United States, and the world.Go to footnote 450 detail His aim was to endow the United States with a museum that would rival the best collections in Europe. Agassiz initially acquired and stored most of the collection at his own cost, raising funds to support the effort from private donors, including Elizabeth Cary Agassiz’s connections among the Boston elite.Go to footnote 451 detail

The search for specimens motivated Agassiz to organize his expedition to Brazil in 1865, in the midst of the Civil War. Polygenist ideas were losing favor following the publication of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species in 1859, and Agassiz identified Brazil as a prime location to continue his research and defend his claims.Go to footnote 452 detail In April 1865, with the support of a Boston financier,Go to footnote 453 detail Agassiz left for Brazil accompanied by Elizabeth and several Harvard students—including William James,Go to footnote 454 detail who would become an influential Harvard psychologist. Meanwhile Alexander Agassiz, now a naturalist in his own right and directly involved in his father’s work, assumed responsibility for the museum and handled Louis’s correspondence, including discussions of the procurement of human remains from South America.Go to footnote 455 detail

Because of the country’s racial diversity and its significant mixed-race population, Brazil had particular significance for Agassiz and other natural scientists of the 19th century.Go to footnote 456 detail In fact, race scientists had long identified Brazil as the embodiment of the dangers of race mixture, which they argued had produced a population that doomed the nation to backwardness.Go to footnote 457 detail Race mixture was Agassiz’s focus when he commissioned a new set of photographs of Brazilian enslaved and free people. Agassiz personally oversaw the production of these images, which were taken by a local photographer and a Harvard student assistant.Go to footnote 458 detail The photographs likely were staged in the courtyard of the house in Brazil where Louis and Elizabeth had at one point resided with the research crew.Go to footnote 459 detail

Louis and Elizabeth cowrote A Journey in Brazil, published in 1868, which documented the expedition and presented their findings to a general audience in the travel narrative genre of the time. In the book’s preface, Louis specifically acknowledged the important role his wife played in the endeavor:

Partly for the entertainment of her friends, partly with the idea that I might make some use of it in knitting together the scientific reports of my journey by a thread of narrative, Mrs. Agassiz began this diary. I soon fell into the habit of giving her daily the more general results of my scientific observations, knowing that she would allow nothing to be lost which was worth preserving.Go to footnote 460 detail

Elizabeth’s own correspondence confirms her deep involvement in writing and editing the manuscript.Go to footnote 461 detail Given this, it is interesting to note that the book remains silent about the Brazil photographs, even as it provides detailed depictions of other episodes, including Louis’s sketch of their house maid. Elizabeth is also thought to have expunged from other publications Louis’s most flagrantly racist views.Go to footnote 462 detail

It is unclear whether the omission of the photographs reflects Elizabeth’s discomfort with Louis’s production of the images, all nude or seminude, her effort to safeguard Louis’s reputation, or some other motivation. Whatever the reason, these omissions underscore Elizabeth’s active participation in the expedition and publication. It is also evident from her work on A Journey in Brazil that she accepted prevailing racial hierarchies and stereotypes. For example, one passage in the book describes a gathering of enslaved people that Elizabeth and the crew witnessed while Louis was elsewhere:

The dance and the song had, like the amusements of the negroes in all lands, an endless monotonous repetition. Looking at their half-naked figures and unintelligent faces, the question arose, so constantly suggested when we come in contact with this race, “What will they do with this great gift of freedom?” The only corrective for the half doubt is to consider the whites side by side with them: whatever one may think of the condition of slavery for the blacks, there can be no question as to its evil effects on their masters.Go to footnote 463 detail

Both Louis and Elizabeth were also interested in educational reform, so it is not surprising that they took time to observe the state of education across Brazil in the course of their travels. In one striking passage, they connect the deficits they perceive in Brazilians’ education with the close contact between enslavers and the enslaved in private homes:

Behind all defects in methods of instruction, there lies a fault of domestic education, to be lamented throughout Brazil. This is the constant association with black servants, and, worse still, with negro children. … Whether the low and vicious habits of the negroes are the result of slavery or not, they cannot be denied; and it is singular to see persons, otherwise careful and conscientious about their children, allowing them to live in the constant companionship of their blacks. … It shows how blind we may become, by custom, to the most palpable dangers.Go to footnote 464 detail

A complicated figure in her own right, some 11 years after the publication of A Journey in Brazil—and 6 years after her husband’s death—Elizabeth played a critically important role in promoting educational access for women through the Harvard Annex, later Radcliffe College. Notably, and notwithstanding the racial prejudices she entertained while working alongside Louis in Brazil, Radcliffe College admitted and graduated Alberta Virginia Scott, its first black alumna, as part of its first graduating class in 1898, during Elizabeth’s tenure as president (1882–1899).Go to footnote 465 detail

Charles William Eliot: A Paradoxical Racial Legacy

Charles William Eliot, Harvard’s longest-serving president, in office for the four decades from 1869 to 1909, was an influential national figure. According to one historian, “by the turn of the century … his opinion and support were sought on every variety of public question.”Go to footnote 466 detail He and his presidential administration represent a paradox: Harvard began admitting small numbers of Black students during his presidency; at the same time, Eliot himself and prominent Harvard faculty members promoted eugenics and endorsed racial segregation.

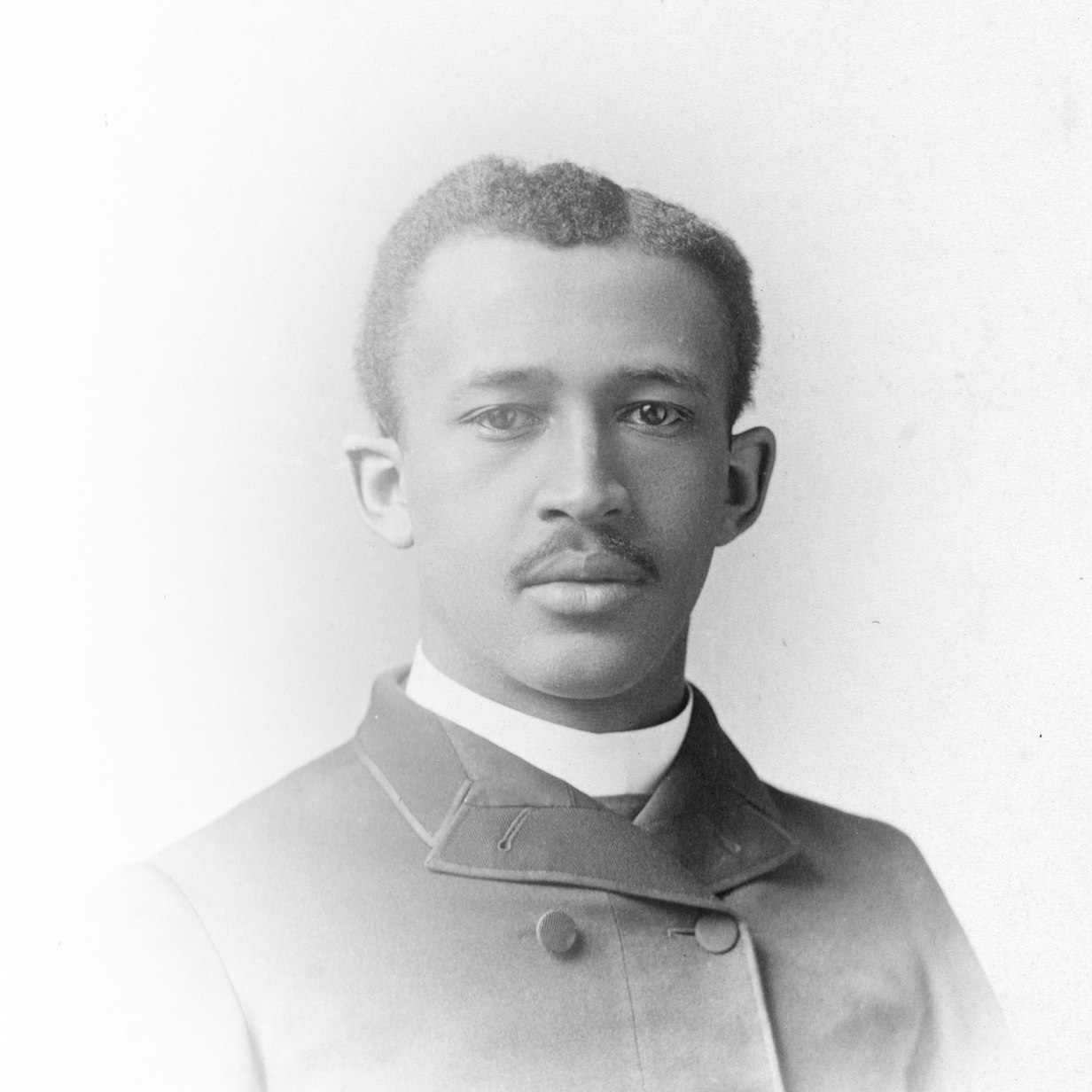

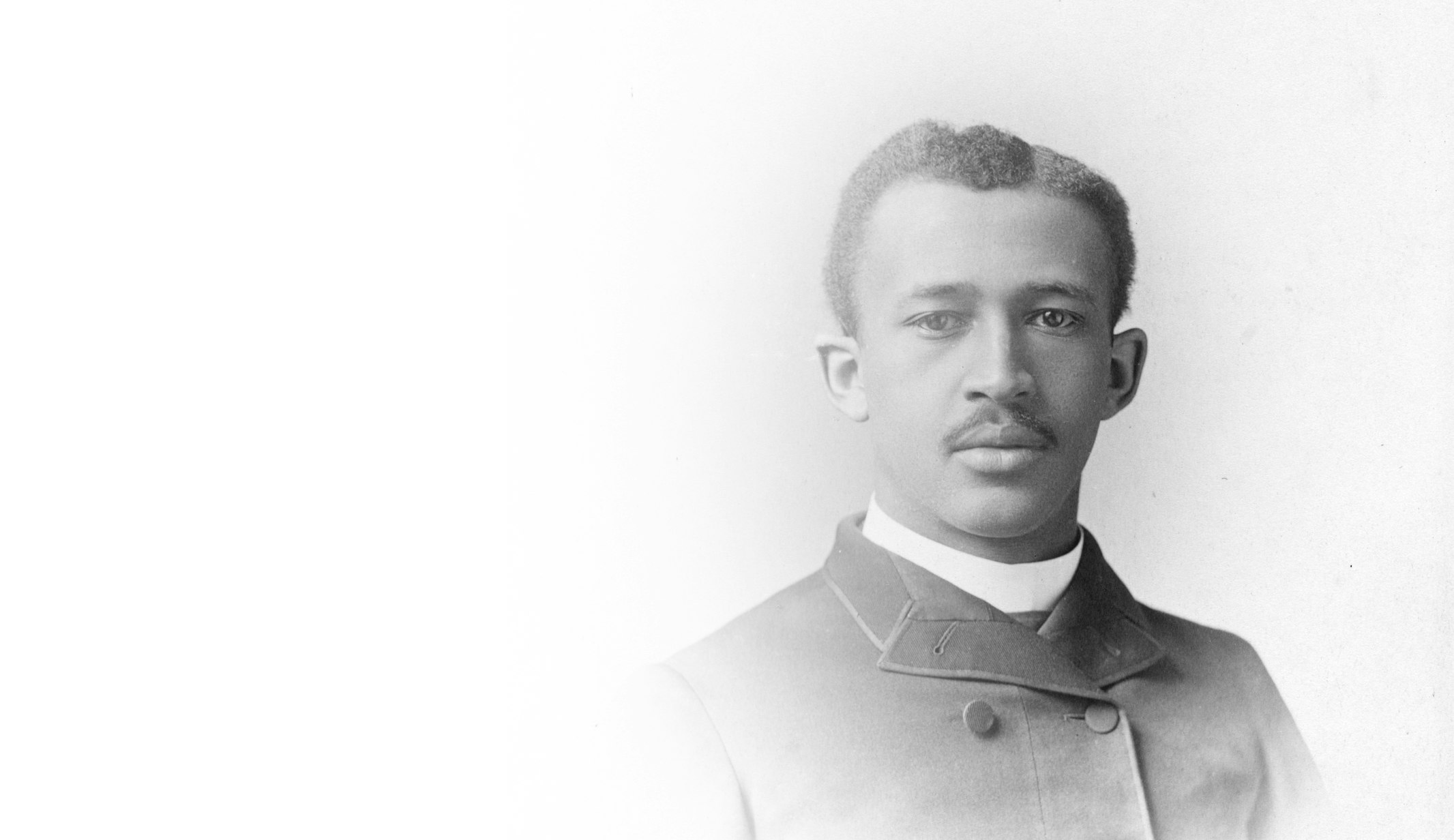

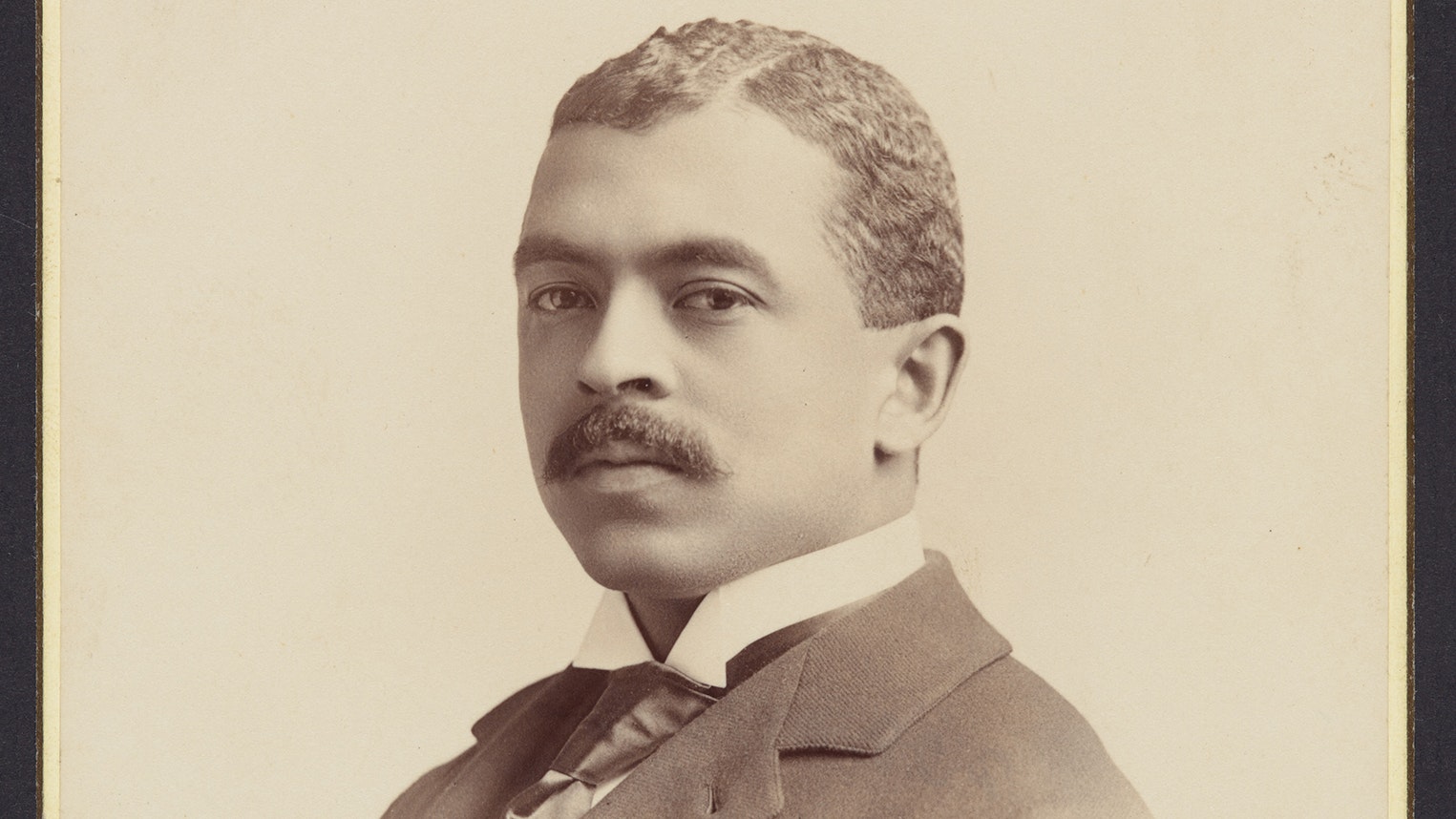

The first Black students to graduate from Harvard did so just two months after Eliot’s election to the presidency.Go to footnote 467 detail The University saw its first Black graduate of the College, Richard T. Greener (AB 1870); first Black commencement orator, Robert H. Terrell (AB 1884); first Black class day speaker, Clement Morgan (AB 1890); and first Black recipient of a PhD, W. E. B. Du Bois (AB 1890; MA 1891; PhD 1895), during this period. Moreover, during Eliot’s administration, William Monroe Trotter (AB 1895; AM 1896) became the first Black member of Phi Beta Kappa and Alain Locke the first Black Rhodes Scholar (1907).Go to footnote 468 detail Eliot’s tenure also saw the hiring of Harvard’s first Black faculty member, George F. Grant.Go to footnote 469 detail

Perhaps the most significant development occurred soon after Eliot became president, and it revealed the paradox at the heart of limited Black advancement at Harvard during his presidency. In 1896, Harvard awarded an honorary degree to a Black man for the very first time: Eliot bestowed the honor upon Booker T. Washington,Go to footnote 470 detail a man who had been born in slavery and who had made a mark as an author and as the principal of the Tuskegee Institute (later the Tuskegee College and today Tuskegee University).Go to footnote 471 detail By awarding Washington an honorary degree, Harvard expressed esteem for a Black man of great ability, and that was no small thing. But that was not all the award to Washington signified: it was a politically significant choice that gave Harvard’s imprimatur to a man who achieved fame by urging Blacks to accommodate rather than fight racial exclusion, discrimination, and segregation.

Just months before Harvard honored him, Washington had gained national renown through his “Atlanta Compromise” address. In this 1895 speech, made to an audience of white Southerners during a time of rising white violence, political backlash, and legalized discrimination against descendants of slavery, Washington argued that Blacks should not agitate for racial equality or challenge segregation. “In all things that are purely social we can be as separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress,” he said.Go to footnote 472 detail Instead of pursuing the “extremest folly” of social equality, Blacks should pursue vocational education and work hard in the South, including manual labor in cotton mills.Go to footnote 473 detail Washington’s proposal amounted to a “conservative social Darwinist proposition,” according to one biographer, and it delighted whites who were eager to leave the race question behind and let Blacks fend for themselves. Washington’s “compromise” enraged Black leaders bent on fighting racial inequality.Go to footnote 474 detail (In 1903, the Harvard graduate W. E. B. Du Bois would famously critique Washington’s views in The Souls of Black Folk.Go to footnote 475 detail)

It was in this context—Washington’s endorsement of Black political quiescence—that Eliot personally awarded the honorary degree to him (and 12 others) during a June 24, 1896, ceremony in Sanders Theatre. Eliot praised Washington’s remarks that evening at an alumni dinner, in which Washington—a self-described “humble representative” of the Black South—commended the “strong,” “wealthy,” and “learned” of Harvard and exhorted them to help the “ignorant” and “weak” masses rise to the “American standard.”Go to footnote 476 detail

But Harvard did relatively little to help Blacks rise during Eliot’s long presidency. Instead, Eliot himself, and Harvard’s leadership more broadly, continued to advance ideas premised on biological racial difference—the same ideas deployed to support racial segregation. Eliot supported faculty who pursued eugenics, the selective breeding of human beings premised on racial hierarchy, and after his presidency would become a prominent public advocate for the field.Go to footnote 477 detail His views were “well within the intellectual mainstream” at Harvard and throughout the country at the time,Go to footnote 478 detail and coexisted with his enthusiasm for applied science as a means to identify new solutions for long-standing social ills. These interests were not merely academic; Eliot’s views were also bound up with his politics—including his endorsement of segregation, opposition to interracial marriage, and support for eugenic sterilization—and shaped his administration of the University.

The Bussey Institution, founded in 1871 as an undergraduate department in agriculture with the proceeds of Boston merchant Benjamin Bussey’s bequest to the University,Go to footnote 479 detail was reestablished under Eliot as a graduate school of applied biology.Go to footnote 480 detail Eliot supported the new school and its faculty, clearing the way for the geneticist William E. Castle’s research into “what principles underlie the improvement of breeds” and his hereditary experiments on small mammals.Go to footnote 481 detail Castle and his ties to the global eugenicist movement are discussed in greater detail below.

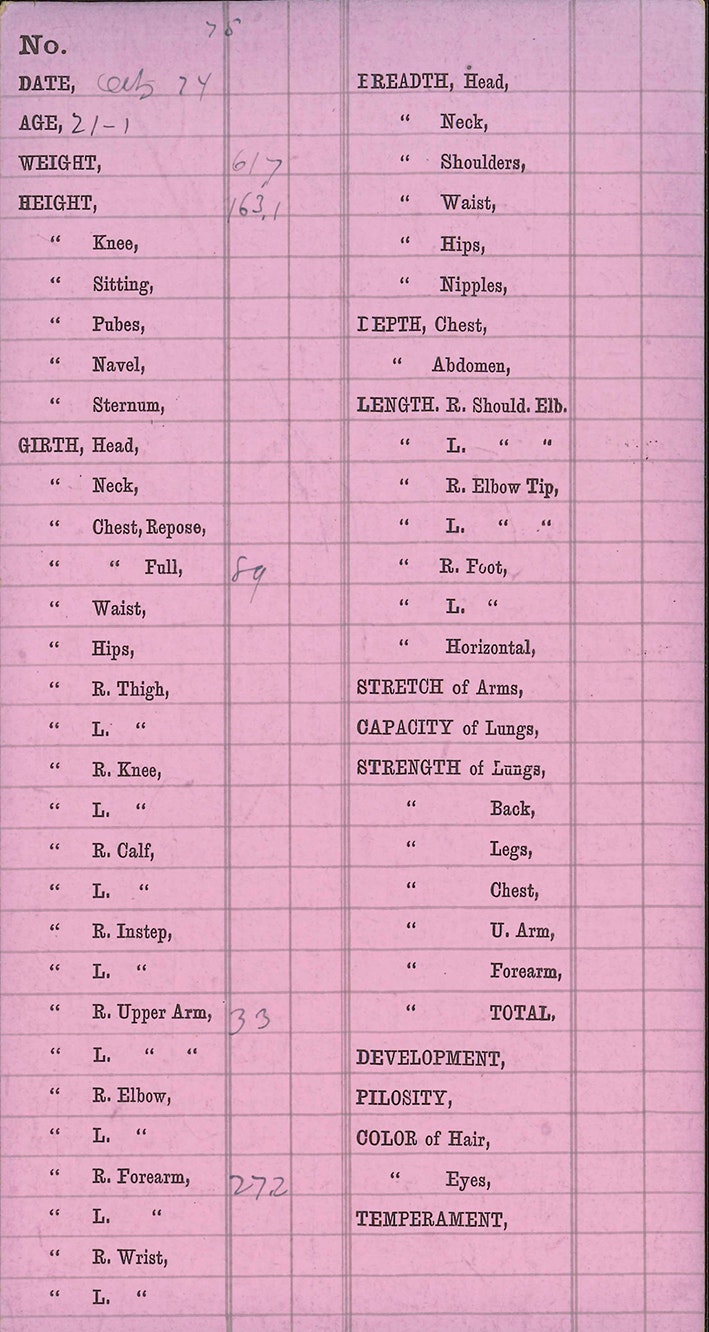

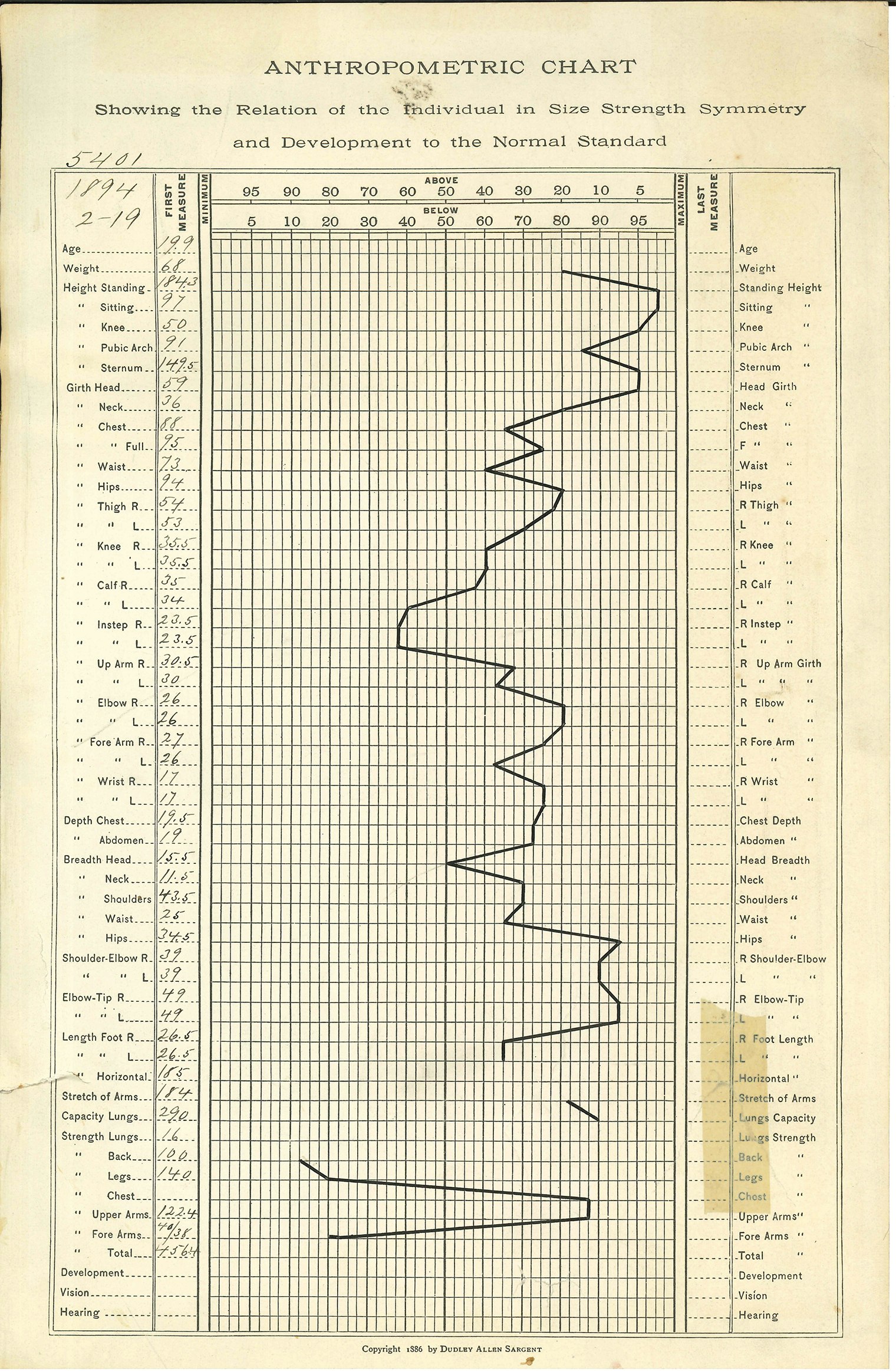

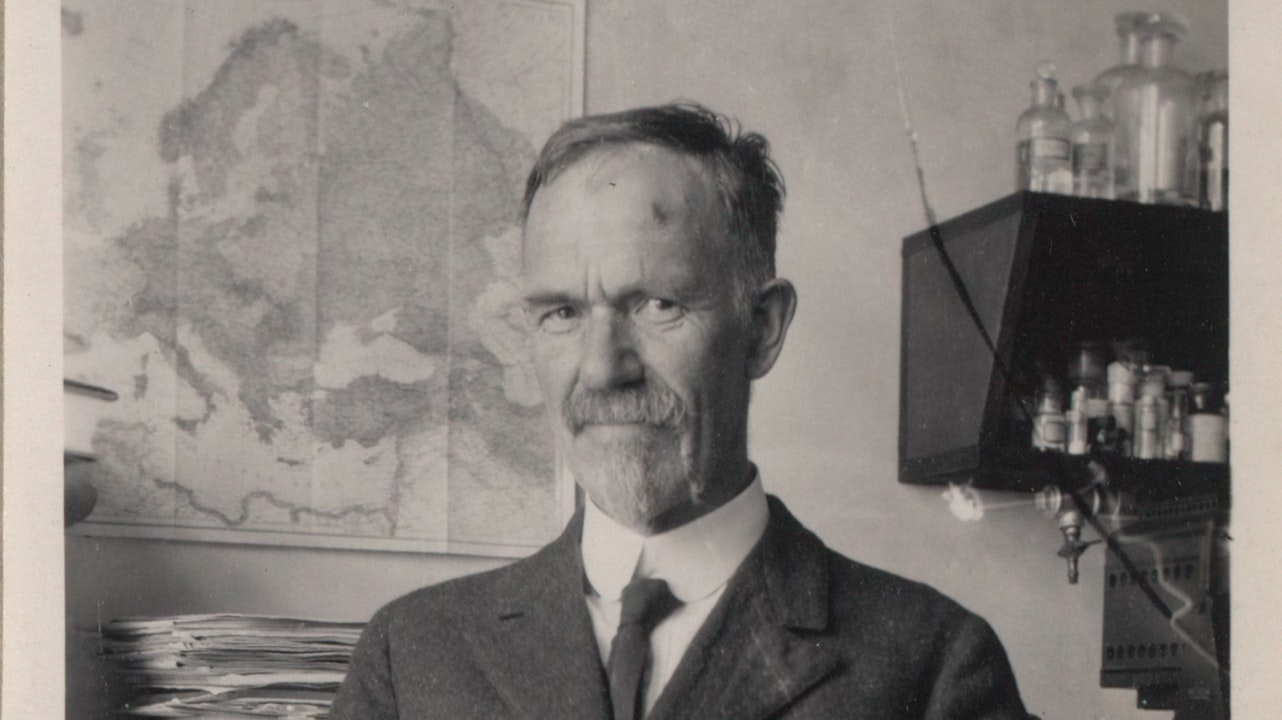

Another beneficiary of Eliot’s support was Dudley Allen Sargent, assistant professor of physical training (1879–1889) and director of Hemenway Gymnasium (1879–1919).Go to footnote 482 detail As head of Hemenway, Sargent established a system of rigorous physical exercises through which students might reform their bodies into the archetypal healthy, civilized man. He also, as described by Eliot, subjected “all students who desired to take part in athletic sports or severe physical exercises” to “thorough physical examination.”Go to footnote 483 detail These intrusive physical examinations and his approach to physical education were motivated by his interest in “race improvement.”Go to footnote 484 detail

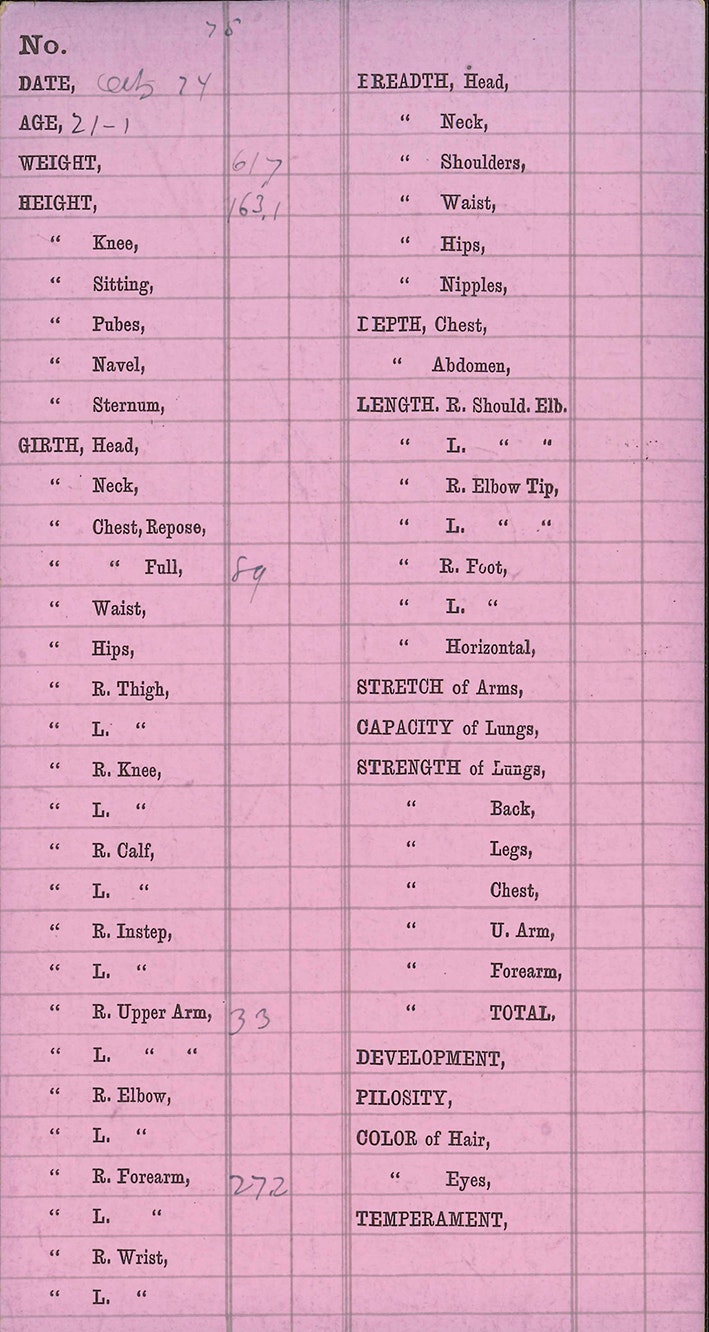

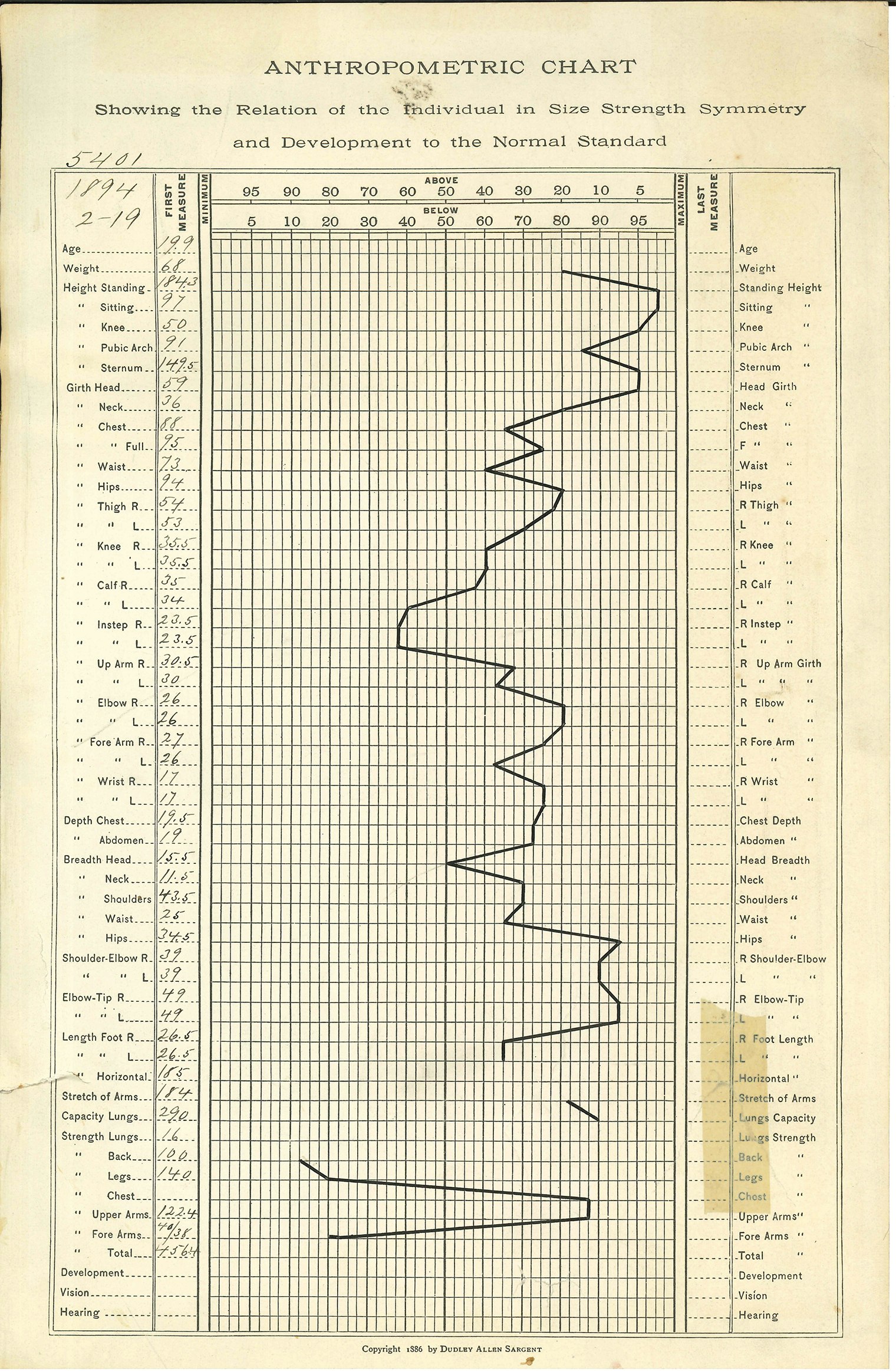

Student athletes subject to Sargent’s anthropometric evaluation began with a genealogical and family health form, which included parents’ and grandparents’ nationalities and parents’ occupations, as well as a question about which parent the students believed they “most resemble[d].” After completing the form, the students’ physical proportions were measured and plotted in a detailed chart that showed “relation, in size, strength, symmetry, and development, to the normal standard of your age and sex.”Go to footnote 485 detail As part of these examinations, Sargent took nude photographs of many students, among them a young W. E. B. Du Bois.Go to footnote 486 detail He also measured and photographed students at Radcliffe and other colleges and universities, as well as men and women at gymnasiums and community organizations, such as YMCAs and YWCAs, and at major public events, including the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago.Go to footnote 487 detail

Sargent used his data to establish normative and idealized measurements for both sexes and commissioned drawings and sculptures to illustrate these findings.Go to footnote 488 detail Like other prominent eugenicists of the period, he was preoccupied with the notion that the white race was deteriorating under conditions of modernity and believed that as nations became more advanced, their citizens became unfit and lax.Go to footnote 489 detail He also openly endorsed racial hierarchy and held that “civilized” or “superior” races could be distinguished from “primitive” or “inferior” races based on body proportions.Go to footnote 490 detail

Eliot was also active in the public sphere, where he touted race science and the virtues of segregation. In the spring of 1909, before stepping down as president,Go to footnote 491 detail Eliot made a tour of the American South, where he was frequently asked to comment on questions of race. While in Memphis, Eliot attempted to address “race problems” in an interview with local reporters.Go to footnote 492 detail The resulting article spread like wildfire, with newspapers across the country, including in Boston, reprinting his statement that “there should be no admixture of racial stock”:

I believe for example, that the Irish should not intermarry with the Americans of English descent; that the Germans should not marry the Italians; that the Jews should not marry the French. Each race should maintain its own individuality. The experience of civilization shows that racial stocks are never mixed with profit, and that such unions do not bring forth the best and strongest children. … In the case of the negroes and the whites, the races should be kept apart in every respect. The South has a wise policy. I believe that Booker T. Washington has the right ideals and that Dubois is injuring the progress of his race with his views.Go to footnote 493 detail

Other newspapers quoted from the same interview Eliot’s comparison of the South to other parts of the United States:

In the South it is the negro problem. The same or similar problems exist in all parts of the country. In protestant Massachusetts, the land of Pilgrims and Puritans, the population today is mostly Catholic. There are Irish, Italian, and Portuguese that present the same race problem to that part of the country that the negroes do to the South. On the Pacific coast it is the same with the Japanese.Go to footnote 494 detail

Following public criticism of these comments, Eliot engaged in damage control; he acknowledged the value of immigrants and attempted to clarify his views on assimilation—namely that it should be gradual rather than sudden and achieved through education, industry, and policy rather than intermarriage. But he did not deny an aversion to racial mixing. While it was common in this era to oppose marriage between races of “widely different characteristics,”Go to footnote 495 detail Eliot had gone further, drawing lines between Europeans. One political cartoon depicted a stern Professor Eliot trying to instill his “no admixture” message in his only student—a laughing cupid.Go to footnote 496 detail

His statements did not go unnoticed by those few Black members of the Harvard community. A month after the interview, in April 1909, William Monroe Trotter wrote to Eliot “as an alumnus of Harvard, as a colored man, and as editor of a newspaper for colored Americans.” Trotter, who cofounded the Niagara Movement, predecessor of the NAACP, with W. E. B. Du Bois, wanted to know if what he was reading in the press was true—whether the president of his alma mater really advocated “total segregation,” approved of “the white South’s method of dealing with colored Americans,” and would concede to “admitting the colored people into the American brotherhood … only after 1000 years of ‘civilization.’”Go to footnote 497 detail

Eliot’s response two days later attempted some clarification of his opinions, which, he noted, were “not newly formed.”Go to footnote 498 detail First, he explained, “The Whites and the Negroes had better live beside each other in entire amity, but separate, under equal laws.” He expressed support for Black suffrage, albeit with a poll tax for all voters, and held that “political equality seems to me to have nothing whatever to do with what is called social equality” and will not lead to “social admixture.”Go to footnote 499 detail He offered his own observations about the South, including his assessment that “it would take four or five generations more to teach the mass of the negro population that civilization is built on willingness to work hard six days in the week, and to be frugal all the time,” partly because it would be “unreasonable to expect that people who had so recently been savages and slaves should all acquire in forty years the primary virtues of civilization.” For good measure, Eliot concluded his letter with the assertion that “as to intermarriage between Whites and Blacks, all the best evidence seems to me to show that it is inexpedient.”Go to footnote 500 detail

When Trotter responded the next day with additional questions about the application of Eliot’s opinions to “actual conditions,” noting that “I believe I am correct in saying the Colored people are quite anxious to know your views,” he received no reply.Go to footnote 501 detail There is likewise no recorded response to Trotter’s second prompt for a reply some five days later.

Eliot’s stature and political savvy set him up to play an active supporting role in the rising eugenics movement in his post-presidency years. He warned that “the increase of liberty for all classes of the community seems to promote the rapid breeding of the defective, irresponsible and vicious” and advocated “preventing the feeble-minded from reproducing their like.”Go to footnote 502 detail He stopped short of other Harvard affiliates—including his secretary, Frank W. Taussig, who went on to become a faculty member and argued that, although society “[had] not reached the stage where we can proceed to chloroform them once for all,” the “feeble minded” could at least be “segregated, shut up in refuges and asylums, and prevented from propagating their kind.”Go to footnote 503 detail

Charles B. Davenport, William E. Castle, and the International Eugenics Movement

As the eugenics movement took hold in the early 20th century, another Harvard affiliate, Charles B. Davenport (AB 1889; AM 1890; PhD 1892), became one of its key leaders.Go to footnote 504 detail Davenport studied biology at Harvard and stayed on as an instructor until 1899, when he joined the faculty of the University of Chicago. In 1910, Davenport and his fellow eugenics leader Harry H. Laughlin established the Eugenics Record Office in Cold Spring Harbor, New York,Go to footnote 505 detail which became a center for the eugenics movement and produced a wide range of research and propaganda.Go to footnote 506 detail His 1911 book, Heredity in Relation to Eugenics, became the standard text for eugenics courses at colleges and universities across the country and was cited by more than a third of high-school biology textbooks of the era.Go to footnote 507 detail Like his fellow eugenicists, Davenport believed in biological differences among races and the distinctiveness and superiority of the white race, and he virulently opposed race mixing. He advocated for racial restrictions on immigration; “selective elimination” of undesirable people; and acceptance of “the principle of the inequality of generating strains” and “eugenical ideals … in mating,” such that “strains with new and better combinations of traits may arise and our nation take front rank in culture among the nations of ancient and modern times.”Go to footnote 508 detail

Davenport had a significant impact on his students during his decade as an instructor at the University. Among them was a young William Ernest Castle, who would himself go on to become a major figure in eugenics at Harvard and in the United States.Go to footnote 509 detail Castle enrolled at Harvard College in 1892, pursuing a second bachelor’s degree—he had previously graduated from Denison University—in botany and zoology. Castle worked as a laboratory assistant for Davenport and completed a PhD under the direction of E. L. Mark, the professor of zoology who had also advised Davenport.Go to footnote 510 detail After teaching for two years at the University of Wisconsin and Knox College, Castle returned to Harvard in 1897 as an instructor and researcher in animal breeding, first at the Museum of Comparative Zoology, later at the Bussey Institution, and then the University’s center for agriculture and horticulture.Go to footnote 511 detail

Castle was a prominent member of the American Breeders’ Association (today the American Genetic Association) and a founding member of the editorial board of the journal Genetics.Go to footnote 512 detail In 1912, he was chosen as a member of the American Consultative Committee at the First International Eugenics Congress in London, where Charles William Eliot was then serving as vice president.Go to footnote 513 detail

From 1910 to 1930, Castle taught Genetics and Eugenics, one of several courses on eugenics offered across Harvard at the time.Go to footnote 514 detail He published his lecture notes in 1916 in the textbook Genetics and Eugenics: A Text-book for Students of Biology and a Reference Book for Animal and Plant Breeders,Go to footnote 515 detail which deployed his research into the breeding of animals to advance eugenicist arguments about humans in a concluding chapter titled “The Possibility and Prospects of Breeding a Better Human Race.”Go to footnote 516 detail On race mixing, Castle argued that “from the viewpoint of a superior race there is nothing to be gained by crossing with an inferior race. … From the viewpoint of the inferior race also the cross is undesirable if the two races live side by side, because each race will despise individuals of mixed race and this will lead to endless friction.”Go to footnote 517 detail Moreover, to prevent the inheritance of undesirable traits, Castle concluded that “segregation” of the “feeble-minded” should be implemented in “schools and institutions under state control.” When “segregation is impracticable,” Castle argued, the “feeble-minded … should not be allowed to marry unless first sterilized.”Go to footnote 518 detail

Such ideas, which led to compulsory sterilization practices in approximately 30 states and between 60,000 and 70,000 cases of eugenic sterilization in the United States,Go to footnote 519 detail were also a primary focus of Davenport’s Eugenics Record Office (ERO).Go to footnote 520 detail The ERO quickly gained national and international prominence, and it sustained a dual mission to carry out research and advocate for eugenic research and eugenic policy among the public.Go to footnote 521 detail The organization received funding from the Gladys and Roland Harriman Foundation, the Rockefeller Foundation, and the Carnegie Corporation of New York—a total of $1.2 million between 1910 and 1940Go to footnote 522 detail—and established European connections, particularly with like-minded proponents of eugenics in interwar Germany.

Indeed, the ERO’s Eugenical News introduced German eugenics to an American audience, praised a Nazi sterilization law that drew on ERO research, and became “the main propagandists for the German eugenical cause.”Go to footnote 523 detail As president of the International Federation of Eugenic Organizations, Davenport himself helped restore German eugenicists to a place of prominence in the international movement after World War I.Go to footnote 524 detail At his alma mater, Davenport arranged for a delegation of German eugenicists to participate in Harvard’s 1936 tercentenary celebration.Go to footnote 525 detail

Footnotes

-

For scholarship discussing the many laws, policies, practices, norms, and attitudes that remained as relics of slavery despite its legal prohibition, see generally Leon F. Litwack, Been in the Storm So Long: The Aftermath of Slavery (New York, NY: Knopf, distributed by Random House, 1979); Hunter, To ‘joy My Freedom; Masur, All the Land; Foner, Forever Free; Franklin, Reconstruction; Ariela J. Gross, What Blood Won’t Tell, 4-5, 9-11, 79-110.

-

See generally Jacobs, Courage and Conscience; Sinha, Slave’s Cause, 41–44, 67–72, 453–454. These antislavery activists, however, encountered significant resistance, see Cutler, Boston Gentleman’s Mob. This history is sometimes forgotten; on the complex association between historical memory in discussions of slavery and antislavery, see Minardi, Making Slavery History, and Araujo, Slavery in the Age of Memory.

-

Cronin, Reforming Boston’s Schools, 5, 25-26; Foner, Reconstruction, 26; Omori, “Race-Neutral Individualism”; Greenwood, “Community within a Community”; Hill, “Ethnicity and Education.”

-

See U.S. Const. amends. XIII, XIV, XV; see also Foner, What is Freedom, chaps. 1-3.

-

On the white vigilante violence that followed formerly enslaved Blacks when they tried to exercise their newly found freedom, see Foner, Reconstruction, 119-123, 425-430; Du Bois, Black Reconstruction, 221-230, describes, for example, the insufficient resources given to the Freedmen’s Bureau, a federal agency designed to aid the formerly enslaved in the South, as the result of political pushback from Southern whites.

-

Morison, Three Centuries of Harvard, 323.

-

Morison, Three Centuries of Harvard, 322. On the Overseers’ aspirations for Harvard during this period, see ibid., 324-331.

-

“Cambridge Anti-Slavery Society Records now available,” The Cambridge Room: Historic tidbits, facts, and notes of interest on Cambridge, Massachusetts brought to you by the Cambridge Public Library's Archivist, updated November 23, 2016, https://thecambridgeroom.wordpress.com/2016/11/23/cambridge-anti-slavery-society-records-now-available/; Harvard faculty titles and terms confirmed in Harvard University, Quinquennial Catalogue, 1636-1915, 104, 108.

-

“No Union with Slave Holders!” The Liberator (Boston, MA), June 14, 1844.

-

Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society Board of Managers, “Officers of the Society,” in Twelfth annual report, presented to the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society, by its Board of Managers, January 24, 1844, with an appendix (Boston, MA: Oliver Johnson, Court Street, 1844). For more on Williams’s anti-slavery views and activism, see John R. McKivigan, ed., The Frederick Douglass Papers, Series Three: Correspondence, Volume 1: 1842-1852 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2009), 102, n. 15; and Mary Elizabeth Williams Papers, MSS 253, Courtesy of Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum, Massachusetts, https://pem.as.atlas-sys.com/repositories/2/resources/644.

-

“Henry Willard Williams, AM, MD,” Harvard Medical School Department of Ophthalmology, accessed January 2, 2022, https://eye.hms.harvard.edu/henrywillardwilliams; “Henry Willard Williams Professorship,” Harvard Medical School Department of Ophthalmology, accessed January 2, 2022, https://eye.hms.harvard.edu/professorships/williams; Harvard University, Quinquennial Catalogue, 1636-1915, 28.

-

Austin Bearse, Reminiscences of Fugitive-Slave Law Days in Boston (Boston, MA: W. Richardson, 1880), 3-5; Harvard faculty titles and terms confirmed in Harvard University, Quinquennial Catalogue, 1636-1915, 50, 76, 185.

-

Roy E. Finkenbine, “Smith, Joshua Bowen (born 1813), Abolitionists,” American National Biography Online, Oxford University Press, 2000.

-

See Section II of this report.

-

Smith appeared frequently in notices in the abolitionist newspaper The Liberator and other like-minded periodicals throughout the decades surrounding the Civil War, which frequently noted his involvement with and financial contributions to antislavery work. See, for example, “Pledges,” The Liberator, June 13, 1856, where Smith was listed as a donor to the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society’s May 1856 Convention, and “Annual Meeting of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society,” National Anti-Slavery Standard, February 5, 1870, where he was noted as a councillor of the meeting alongside the well-known abolitionist and Harvard graduate Wendell Phillips.

Smith also appears to have been a colleague of noted Black Bostonian abolitionist and writer William Cooper Nell, who mentioned him as both a source and a co-petitioner in The Colored Patriots of the American Revolution, with sketches of several Distinguished Colored Persons: to which is added a brief survey of the Condition and Prospects of Colored Americans, with an introduction by Harriet Beecher Stowe (Boston, MA: Robert F. Walcutt, 1855), https://books.google.com/books?id=Jy8OAAAAIAAJ.

-

Bearse, Fugitive-Slave Law Days, 5, and William Henry Siebert, The Underground Railroad from Slavery to Freedom, with an introduction by Albert Bushnell Hart (New York, NY: The MacMillan Company, 1898), 437, https://books.google.com/books?id=yspuBhJWS9sC.

-

Bearse, Fugitive-Slave Law Days, 6, 36, and Siebert, Underground Railroad, 412.

-

Mary Ellen Snodgrass, “Smith, Joshua Bowen,” The Underground Railroad: An Encyclopedia of People, Places, and Operations (Armonk, NY: Routledge, 2008), 499.

-

“Cambridge Anti-Slavery Society Records,” Cambridge Public Library.

-

Eliza Lee Cabot Follen, The Life of Charles Follen (Boston, MA: Thomas H. Webb and Company, 1844), 227–237, https://books.google.com/books?id=5zCWAZzVRq4C.

-

John Ware, Memoir of the Life of Henry Ware Jr. (Boston, MA: James Munroe and Co, 1846), 361–362. See also Bosco, “Fugitive Slave Act,” 228–229; Wilder, Ebony & Ivy, 278–280.

Ware’s widow clearly believed her husband had been persecuted by Harvard administration because of his views: In an 1845 exchange with then former Harvard President Josiah Quincy she asked, “if at any time, during [my] husband’s connection with the University, he was required by the Corporation to suppress the expression of his opinion upon the subject of slavery as being a condition of holding his Professorship?” Quincy denied that this was the case. “Josiah Quincy to Miss Mary L. Ware, April 22, 1845.” Josiah Quincy to Mary L. Ware, April 22, 1845, box 4, Corporation Papers, 1845–46, Corporation Papers, 2nd ser., supplements to the Harvard College Papers, UAI 5.130, Harvard University Archives.

-

“Slavery and Abolition in the Longfellow Archives,” Longfellow House Washington’s Headquarters, National Park Service, accessed February 4, 2022, https://www.nps.gov/long/learn/historyculture/slavery-related-objects-at-longfellow-nhs.htm.

-

Frederick J. Blue, “The Poet and the Reformer: Longfellow, Sumner, and the Bonds of Male Friendship, 1837-1874,” Journal of the Early Republic 15, no. 2 (Summer 1995): 280-285.

-

Christoph Irmscher, who has written biographies of both men, characterizes Longfellow as “Agassiz’s closest friend.” Louis Agassiz: Creator of American Science (New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2013), 14–15, 18, 21, 25.

-

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Poems on Slavery, 2nd ed. (Cambridge, MA: J. Owen, 1842), 23-25, https://books.google.com/books?id=DqxcAAAAcAAJ; Christoph Irmscher, Public Poet, Private Man: Henry Wadsworth Longfellow at 200 (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2009), 118.

-