Charles William Eliot: A Paradoxical Racial Legacy

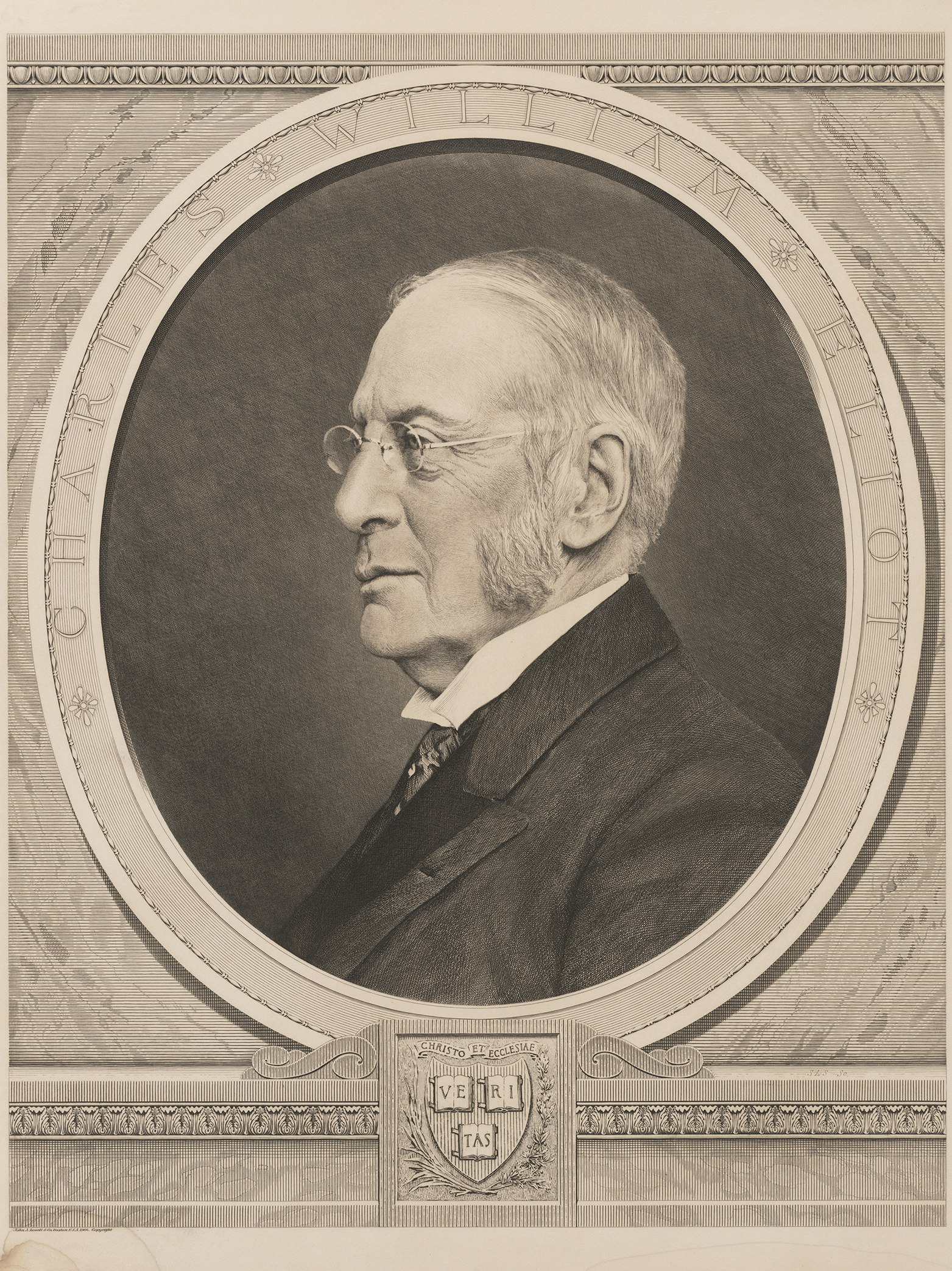

Charles William Eliot, Harvard’s longest-serving president, in office for the four decades from 1869 to 1909, was an influential national figure. According to one historian, “by the turn of the century … his opinion and support were sought on every variety of public question.”Go to footnote 466 detail He and his presidential administration represent a paradox: Harvard began admitting small numbers of Black students during his presidency; at the same time, Eliot himself and prominent Harvard faculty members promoted eugenics and endorsed racial segregation.

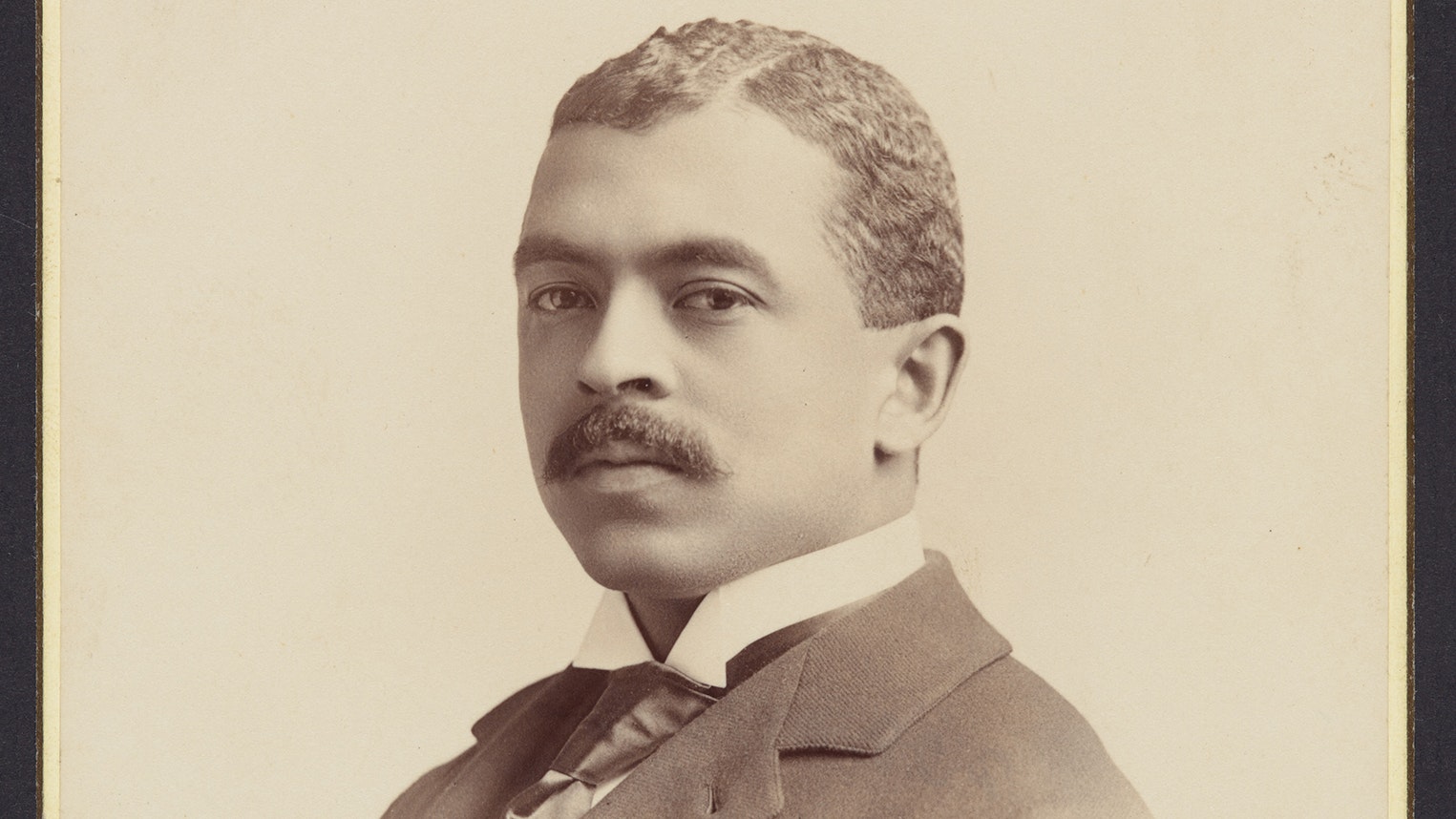

The first Black students to graduate from Harvard did so just two months after Eliot’s election to the presidency.Go to footnote 467 detail The University saw its first Black graduate of the College, Richard T. Greener (AB 1870); first Black commencement orator, Robert H. Terrell (AB 1884); first Black class day speaker, Clement Morgan (AB 1890); and first Black recipient of a PhD, W. E. B. Du Bois (AB 1890; MA 1891; PhD 1895), during this period. Moreover, during Eliot’s administration, William Monroe Trotter (AB 1895; AM 1896) became the first Black member of Phi Beta Kappa and Alain Locke the first Black Rhodes Scholar (1907).Go to footnote 468 detail Eliot’s tenure also saw the hiring of Harvard’s first Black faculty member, George F. Grant.Go to footnote 469 detail

Perhaps the most significant development occurred soon after Eliot became president, and it revealed the paradox at the heart of limited Black advancement at Harvard during his presidency. In 1896, Harvard awarded an honorary degree to a Black man for the very first time: Eliot bestowed the honor upon Booker T. Washington,Go to footnote 470 detail a man who had been born in slavery and who had made a mark as an author and as the principal of the Tuskegee Institute (later the Tuskegee College and today Tuskegee University).Go to footnote 471 detail By awarding Washington an honorary degree, Harvard expressed esteem for a Black man of great ability, and that was no small thing. But that was not all the award to Washington signified: it was a politically significant choice that gave Harvard’s imprimatur to a man who achieved fame by urging Blacks to accommodate rather than fight racial exclusion, discrimination, and segregation.

Just months before Harvard honored him, Washington had gained national renown through his “Atlanta Compromise” address. In this 1895 speech, made to an audience of white Southerners during a time of rising white violence, political backlash, and legalized discrimination against descendants of slavery, Washington argued that Blacks should not agitate for racial equality or challenge segregation. “In all things that are purely social we can be as separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress,” he said.Go to footnote 472 detail Instead of pursuing the “extremest folly” of social equality, Blacks should pursue vocational education and work hard in the South, including manual labor in cotton mills.Go to footnote 473 detail Washington’s proposal amounted to a “conservative social Darwinist proposition,” according to one biographer, and it delighted whites who were eager to leave the race question behind and let Blacks fend for themselves. Washington’s “compromise” enraged Black leaders bent on fighting racial inequality.Go to footnote 474 detail (In 1903, the Harvard graduate W. E. B. Du Bois would famously critique Washington’s views in The Souls of Black Folk.Go to footnote 475 detail)

It was in this context—Washington’s endorsement of Black political quiescence—that Eliot personally awarded the honorary degree to him (and 12 others) during a June 24, 1896, ceremony in Sanders Theatre. Eliot praised Washington’s remarks that evening at an alumni dinner, in which Washington—a self-described “humble representative” of the Black South—commended the “strong,” “wealthy,” and “learned” of Harvard and exhorted them to help the “ignorant” and “weak” masses rise to the “American standard.”Go to footnote 476 detail

But Harvard did relatively little to help Blacks rise during Eliot’s long presidency. Instead, Eliot himself, and Harvard’s leadership more broadly, continued to advance ideas premised on biological racial difference—the same ideas deployed to support racial segregation. Eliot supported faculty who pursued eugenics, the selective breeding of human beings premised on racial hierarchy, and after his presidency would become a prominent public advocate for the field.Go to footnote 477 detail His views were “well within the intellectual mainstream” at Harvard and throughout the country at the time,Go to footnote 478 detail and coexisted with his enthusiasm for applied science as a means to identify new solutions for long-standing social ills. These interests were not merely academic; Eliot’s views were also bound up with his politics—including his endorsement of segregation, opposition to interracial marriage, and support for eugenic sterilization—and shaped his administration of the University.

The Bussey Institution, founded in 1871 as an undergraduate department in agriculture with the proceeds of Boston merchant Benjamin Bussey’s bequest to the University,Go to footnote 479 detail was reestablished under Eliot as a graduate school of applied biology.Go to footnote 480 detail Eliot supported the new school and its faculty, clearing the way for the geneticist William E. Castle’s research into “what principles underlie the improvement of breeds” and his hereditary experiments on small mammals.Go to footnote 481 detail Castle and his ties to the global eugenicist movement are discussed in greater detail below.

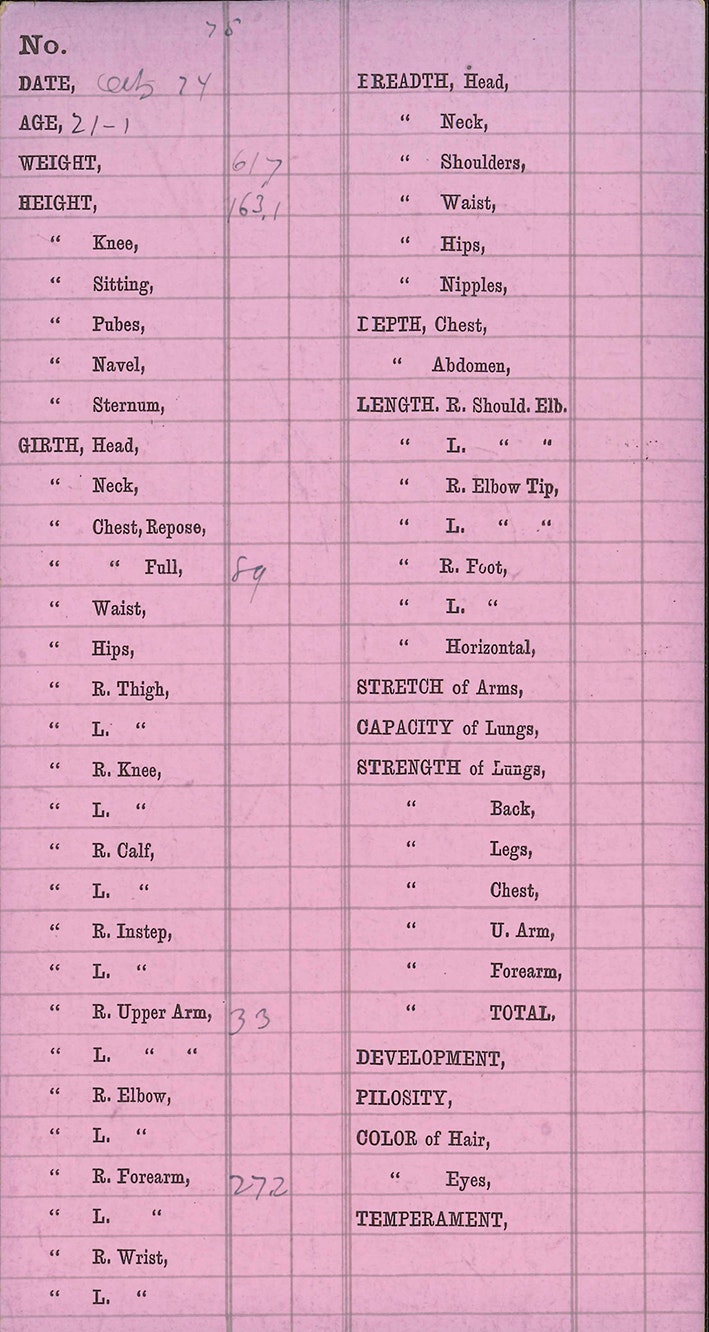

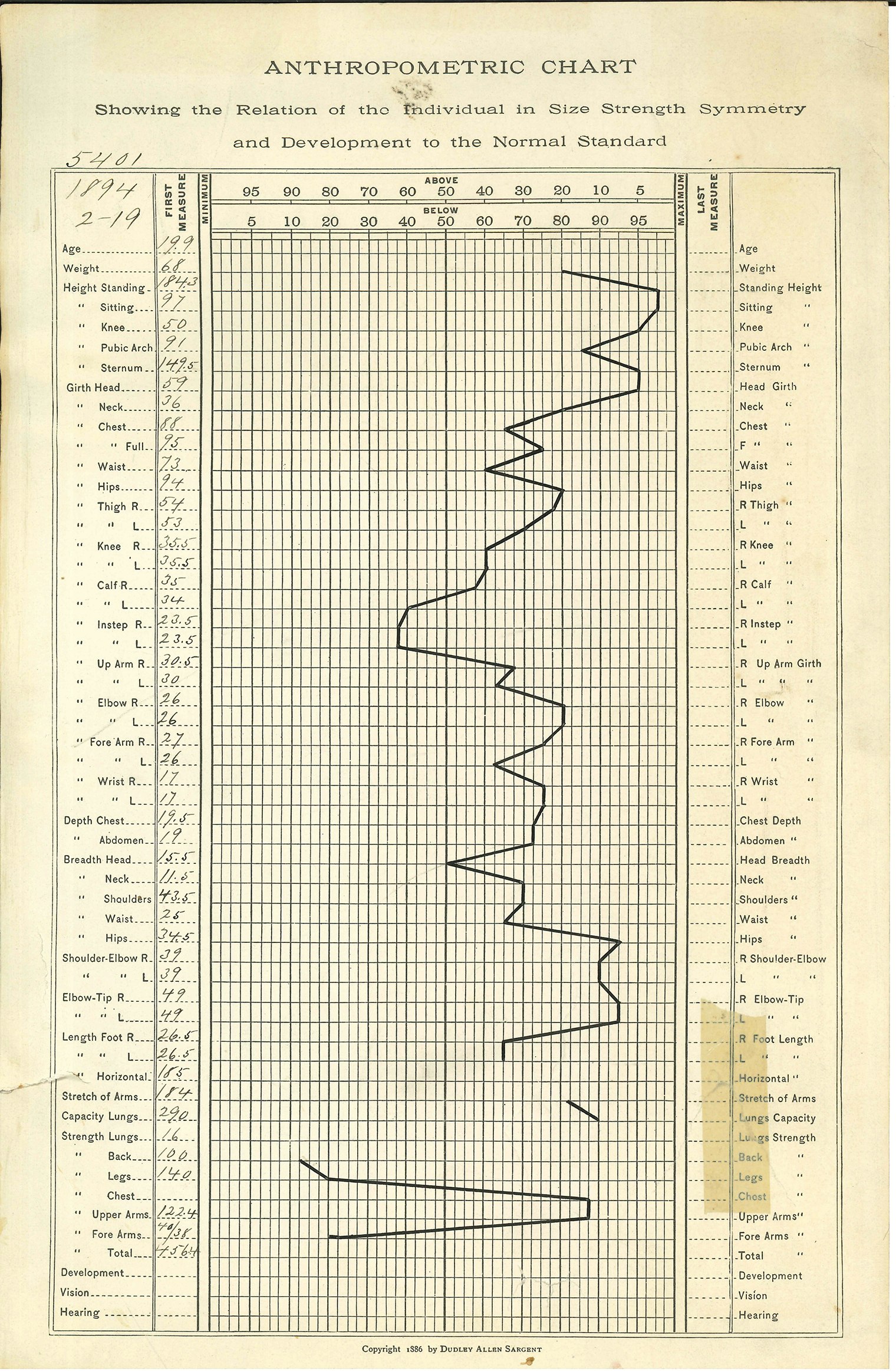

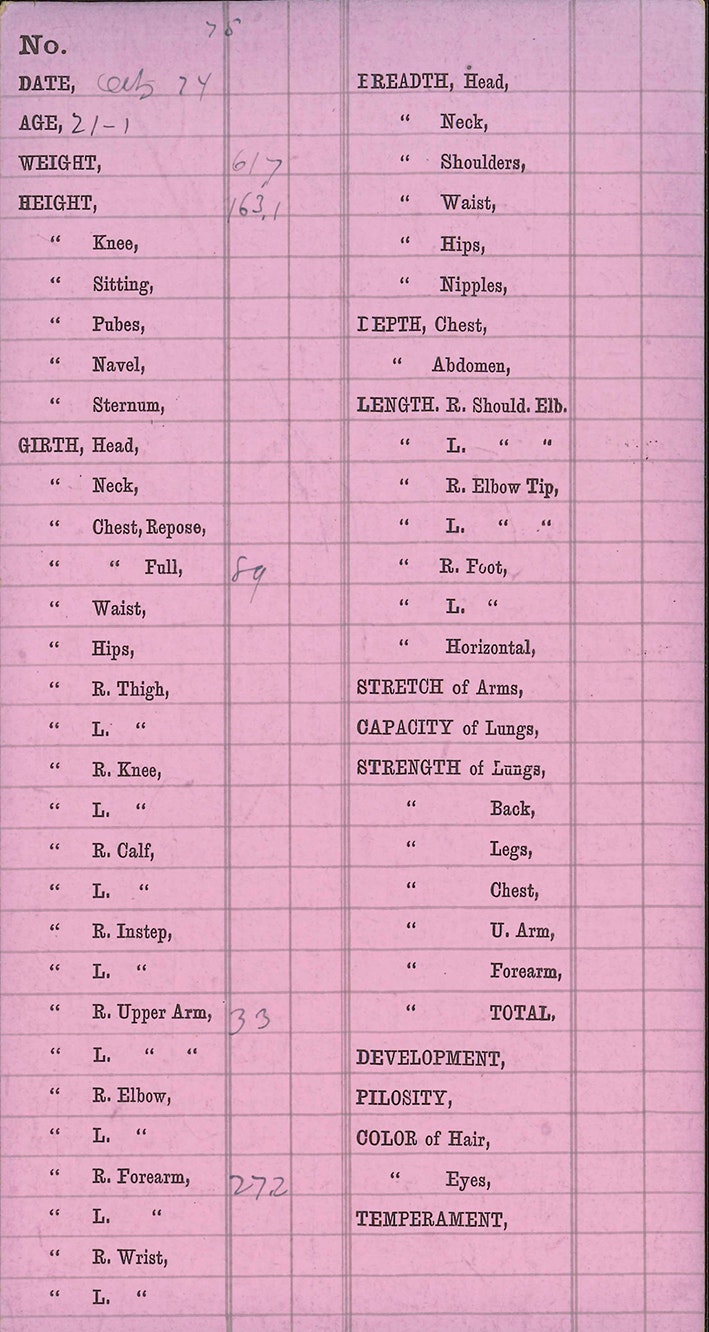

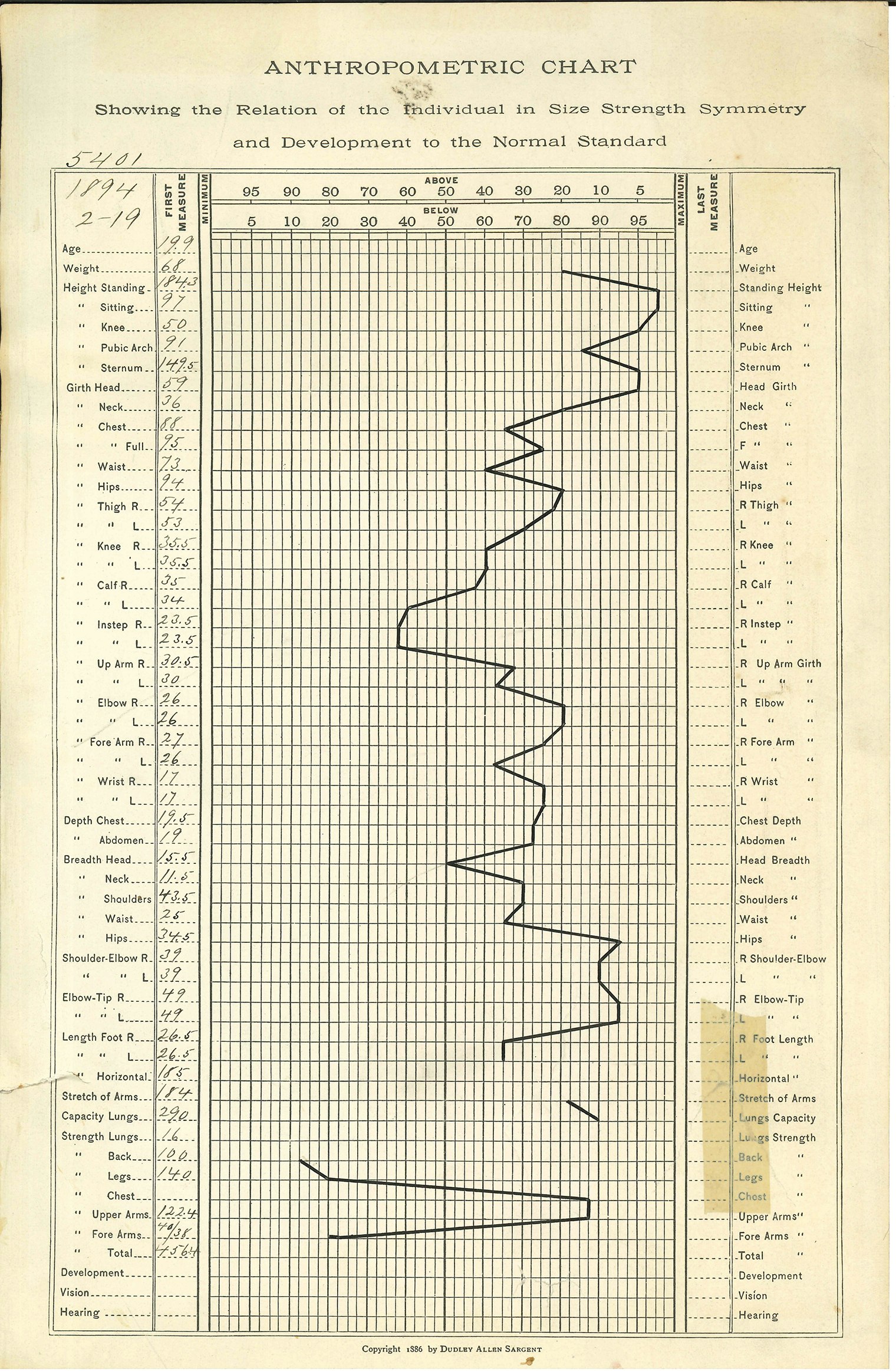

Another beneficiary of Eliot’s support was Dudley Allen Sargent, assistant professor of physical training (1879–1889) and director of Hemenway Gymnasium (1879–1919).Go to footnote 482 detail As head of Hemenway, Sargent established a system of rigorous physical exercises through which students might reform their bodies into the archetypal healthy, civilized man. He also, as described by Eliot, subjected “all students who desired to take part in athletic sports or severe physical exercises” to “thorough physical examination.”Go to footnote 483 detail These intrusive physical examinations and his approach to physical education were motivated by his interest in “race improvement.”Go to footnote 484 detail

Student athletes subject to Sargent’s anthropometric evaluation began with a genealogical and family health form, which included parents’ and grandparents’ nationalities and parents’ occupations, as well as a question about which parent the students believed they “most resemble[d].” After completing the form, the students’ physical proportions were measured and plotted in a detailed chart that showed “relation, in size, strength, symmetry, and development, to the normal standard of your age and sex.”Go to footnote 485 detail As part of these examinations, Sargent took nude photographs of many students, among them a young W. E. B. Du Bois.Go to footnote 486 detail He also measured and photographed students at Radcliffe and other colleges and universities, as well as men and women at gymnasiums and community organizations, such as YMCAs and YWCAs, and at major public events, including the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago.Go to footnote 487 detail

Sargent used his data to establish normative and idealized measurements for both sexes and commissioned drawings and sculptures to illustrate these findings.Go to footnote 488 detail Like other prominent eugenicists of the period, he was preoccupied with the notion that the white race was deteriorating under conditions of modernity and believed that as nations became more advanced, their citizens became unfit and lax.Go to footnote 489 detail He also openly endorsed racial hierarchy and held that “civilized” or “superior” races could be distinguished from “primitive” or “inferior” races based on body proportions.Go to footnote 490 detail

Eliot was also active in the public sphere, where he touted race science and the virtues of segregation. In the spring of 1909, before stepping down as president,Go to footnote 491 detail Eliot made a tour of the American South, where he was frequently asked to comment on questions of race. While in Memphis, Eliot attempted to address “race problems” in an interview with local reporters.Go to footnote 492 detail The resulting article spread like wildfire, with newspapers across the country, including in Boston, reprinting his statement that “there should be no admixture of racial stock”:

I believe for example, that the Irish should not intermarry with the Americans of English descent; that the Germans should not marry the Italians; that the Jews should not marry the French. Each race should maintain its own individuality. The experience of civilization shows that racial stocks are never mixed with profit, and that such unions do not bring forth the best and strongest children. … In the case of the negroes and the whites, the races should be kept apart in every respect. The South has a wise policy. I believe that Booker T. Washington has the right ideals and that Dubois is injuring the progress of his race with his views.Go to footnote 493 detail

Other newspapers quoted from the same interview Eliot’s comparison of the South to other parts of the United States:

In the South it is the negro problem. The same or similar problems exist in all parts of the country. In protestant Massachusetts, the land of Pilgrims and Puritans, the population today is mostly Catholic. There are Irish, Italian, and Portuguese that present the same race problem to that part of the country that the negroes do to the South. On the Pacific coast it is the same with the Japanese.Go to footnote 494 detail

Following public criticism of these comments, Eliot engaged in damage control; he acknowledged the value of immigrants and attempted to clarify his views on assimilation—namely that it should be gradual rather than sudden and achieved through education, industry, and policy rather than intermarriage. But he did not deny an aversion to racial mixing. While it was common in this era to oppose marriage between races of “widely different characteristics,”Go to footnote 495 detail Eliot had gone further, drawing lines between Europeans. One political cartoon depicted a stern Professor Eliot trying to instill his “no admixture” message in his only student—a laughing cupid.Go to footnote 496 detail

His statements did not go unnoticed by those few Black members of the Harvard community. A month after the interview, in April 1909, William Monroe Trotter wrote to Eliot “as an alumnus of Harvard, as a colored man, and as editor of a newspaper for colored Americans.” Trotter, who cofounded the Niagara Movement, predecessor of the NAACP, with W. E. B. Du Bois, wanted to know if what he was reading in the press was true—whether the president of his alma mater really advocated “total segregation,” approved of “the white South’s method of dealing with colored Americans,” and would concede to “admitting the colored people into the American brotherhood … only after 1000 years of ‘civilization.’”Go to footnote 497 detail

Eliot’s response two days later attempted some clarification of his opinions, which, he noted, were “not newly formed.”Go to footnote 498 detail First, he explained, “The Whites and the Negroes had better live beside each other in entire amity, but separate, under equal laws.” He expressed support for Black suffrage, albeit with a poll tax for all voters, and held that “political equality seems to me to have nothing whatever to do with what is called social equality” and will not lead to “social admixture.”Go to footnote 499 detail He offered his own observations about the South, including his assessment that “it would take four or five generations more to teach the mass of the negro population that civilization is built on willingness to work hard six days in the week, and to be frugal all the time,” partly because it would be “unreasonable to expect that people who had so recently been savages and slaves should all acquire in forty years the primary virtues of civilization.” For good measure, Eliot concluded his letter with the assertion that “as to intermarriage between Whites and Blacks, all the best evidence seems to me to show that it is inexpedient.”Go to footnote 500 detail

When Trotter responded the next day with additional questions about the application of Eliot’s opinions to “actual conditions,” noting that “I believe I am correct in saying the Colored people are quite anxious to know your views,” he received no reply.Go to footnote 501 detail There is likewise no recorded response to Trotter’s second prompt for a reply some five days later.

Eliot’s stature and political savvy set him up to play an active supporting role in the rising eugenics movement in his post-presidency years. He warned that “the increase of liberty for all classes of the community seems to promote the rapid breeding of the defective, irresponsible and vicious” and advocated “preventing the feeble-minded from reproducing their like.”Go to footnote 502 detail He stopped short of other Harvard affiliates—including his secretary, Frank W. Taussig, who went on to become a faculty member and argued that, although society “[had] not reached the stage where we can proceed to chloroform them once for all,” the “feeble minded” could at least be “segregated, shut up in refuges and asylums, and prevented from propagating their kind.”Go to footnote 503 detail

Footnotes

-

Samuel Eliot Morison is quoted in the section on Charles William Eliot on “History of the Presidency,” Office of the President, Harvard University, accessed May 25, 2021, https://www.harvard.edu/president/history.

-

On Eliot’s election to the presidency: Henry James, Charles W. Eliot, President of Harvard University, 1869-1909, vol. 1 (Boston, MA and New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1930), 194-195; Edwin C. J. T. Howard, George L. Ruffin, and Robert Tanner Freeman graduated from the medical, law, and dental schools respectively in 1869. See Sollors et al., eds., Blacks at Harvard.

-

Sollors et al., eds., Blacks at Harvard, 2-3; Synnott, The Half-Opened Door, 48.

-

Sollors et al., eds., Blacks at Harvard, 6. Eliot himself was Grant’s dental patient.

-

Harvard University, Quinquennial Catalogue, 1636-1915, 846.

-

See, for example, Louis R. Harlan, Booker T. Washington: The Wizard of Tuskegee, 1901-1915 (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1983).

-

Harlan, Booker T. Washington, 1901-1915, vii-viii.

-

“A Plea for His Race: Booker T. Washington Tells about the Efforts of the Negro,” The Atlanta Constitution September 19, 1895. Reprinted in Louis R. Harlan, ed., The Booker T. Washington Papers, vol. 3, 1889-1895 (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1974), 586.

-

Harlan, Booker T. Washington, 1901-1915, 33.

-

Harlan, Booker T. Washington, 1901-1915, 50-51.

-

See Address of Booker T. Washington: delivered at the alumni dinner of Harvard University Cambridge, Mass., after receiving the honorary degree of “Master of Arts” (Boston, MA: B. T. Washington, 1896), PDF, https://www.loc.gov/resource/lcrbmrp.t0f13/.

-

Sollors et al., Blacks at Harvard, xviii. Nathaniel Southgate Shaler, who once served as Louis Agassiz’s assistant, became dean of the Lawrence Scientific School in 1891. See Irmscher, Louis Agassiz, 263–265; David N. Livingstone, “Science and Society: Nathaniel S. Shaler and Racial Ideology,” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 9, no. 2 (1984): 181–210. Henry Eustis, who died in 1885, also served as dean of the Lawrence Scientific School, see “Prof. Henry Lawrence Eustis,” Harvard Crimson, January 13, 1885, https://www.thecrimson.com/article/1885/1/13/prof-henry-lawrence-eustis-on-sunday.

-

Cohen, “Harvard’s Eugenics Era.”

-

See Section III of this report.

-

William Morton Wheeler, “The Bussey Institution, 1871-1929,” chap. 31 in The Development of Harvard University since the Inauguration of President Eliot, 1869-1929, ed. Samuel Eliot Morison (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013), 513-514. After William Castle’s retirement in 1936 and the death of another primary faculty member in 1938, the Massachusetts Department of Public Health acquired the property and the Institution’s operations effectively merged with the Division of Biological Sciences in the 1960s. See Karl Sax, “The Bussey Institution: Harvard University Graduate School of Applied Biology: 1908-1936,” The Journal of Heredity 57, no. 5 (September 1966): 178.

-

William Ernest Castle to Charles W. Eliot, March 8, 1907, and March 7, 1908, unspecified: box 80, Castle, William Ernest, 1905-1908, Records of the President of Harvard University, Charles W. Eliot, UAI 5.150, Harvard University Archives. On Eliot’s involvement in convincing Castle to remain at Harvard, see J. A. Weir, “Harvard, Agriculture, and the Bussey Institution,” Genetics 136, no. 4 (April 1994): 1227-1231.

-

Harvard University, Quinquennial Catalogue of the Officers and Graduates of Harvard University, 1636-1920 (Cambridge MA: Harvard University, 1920), 108, https://books.google.com/books?id=aQpLAQAAMAAJ.

Sargent is also the namesake of the Sargent College of Health and Rehabilitative Sciences at Boston University, which acquired the Sargent School of Physical Training in 1929, see “Our History,” Boston University College of Health and Rehabilitative Sciences: Sargent College, accessed February 9, 2022, https://www.bu.edu/sargent/about-us/our-history/.

-

Josiah Royce and Charles William Eliot, Dudley Allen Sargent: fiftieth anniversary, 1869–1919 (Cambridge, MA: Sargent School for Physical Education, 1919?), 6.

Sargent’s project also brings to mind the history of “posture photographs” at Ivy League and Seven Sisters institutions well into the 20th century, but further research is necessary to determine the ways in which these efforts were connected. See, for example, Ron Rosenbaum, “The Great Ivy League Nude Posture Photo Scandal,” New York Times, January 15, 1995, https://nyti.ms/3hYy4uE.

-

Dudley Allen Sargent, “Physical Education in Relation to Race Improvement,” (speech, Race Betterment Conference, Battle Creek, MI, January 6-10, 1918), GV342 Sa73pei Sargent, D.A., Relation of Physical Education to Race Improvement, 1914, box 11, Papers of Dudley Allen Sargent, HUG 1768.4, Harvard University Archives.

-

Preliminary forms for 17600-17854, box 29, Records of the Department of Physical Education: anthropometric measurements of Harvard students, 1860-1920, UAV 689.270.1, Harvard University Archives; Class of 1860-1865, box 1, Records of the Department of Physical Education: anthropometric measurements of Harvard students, 1860-1920, UAV 689.270, Harvard University Archives; Dudley Allen Sargent, Anthropometric Apparatus with Directions for Measuring and Testing the Principal Physical Characteristics of the Human Body, 2nd ed. (Cambridge, MA: self pub., 1887), https://books.google.com/books?id=mphAAQAAIAAJ; Ledyard W. Sargent, ed., Dudley Allen Sargent: an autobiography (Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger, 1927); Dudley Allen Sargent, Handbook of Developing Exercises (Boston, MA: Rand, Avery, & Co., 1882), https://books.google.com/books?id=uCEAAAAAYAAJ.

-

“Du Bois, W. E. B. (William Edward Burghardt), 1868-1963, Anthropometric chart, 1888.” W. E. B. Du Bois Papers, MS 312, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries, http://credo.library.umass.edu/view/full/mums312-b237-i156 and Anthropometric chart and photograph of W.E.B. Du Bois, #3129, box 9, Records of the Department of Physical Education: anthropometric measurements of Harvard students, 1860-1920, UAV 689.270.7p, Harvard University Archives.

-

“Collection Organization,” Dudley Allen Sargent measurement cards from schools and organizations other than Harvard, 1880-1920, HUG 1768.60, Harvard University Archives, accessed February 9, 2022, https://id.lib.harvard.edu/ead/hua02003/catalog.

-

See Dudley Allen Sargent, “The Physical Characteristics of the Athlete,” Scribner’s Magazine 2, no. 5 (November 1887): 541-561, with an extract reprinted in Harvard Crimson, November 8, 1887, accessed March 9, 2022, https://www.thecrimson.com/article/1887/11/8/the-physical-characteristics-of-the-athlete/. See also Peter Cryle and Elizabeth Stephens, “The Object of Normality: Composite Statues of the Statistically Average American Man and Woman, 1890-1945,” chap. 7 in Normality: A Critical Genealogy (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2017).

-

Dudley Allen Sargent, “Is War a Biological Necessity?” American Physical Education Review 20, no. 3 (March 1915): 142.

-

For example, at a 1914 conference Sargent discussed concerns about “race suicide” due to declining birth rates in some countries because, as he explained it, “inferior races and individuals tend to multiply more rapidly than the superior races.” Sargent, “Physical Education in Relation to Race Improvement." See also Dudley Allen Sargent, "The Physical Development of Women,” Scribner's Magazine 5, no. 2 (February 1889).

-

James, Charles W. Eliot, 1869–1909, vol. 1: xv.

-

“Mixture of Kindred Races,” San Francisco Chronicle, March 23, 1909, unspecified: box 222, folder 279, Race Blending, Records of the President of Harvard University, Charles W. Eliot, UAI 5.150, Harvard University Archives.

-

“President Eliot Believes Intermarriage of Races Is Bad for All Concerned,” Post (St. Louis, MO), n.d., unspecified: box 222, folder 279, Race Blending, Records of the President of Harvard University, Charles W. Eliot, UAI 5.150, Harvard University Archives.

-

“Aroused By Eliot Attack on Races,” Traveller (Boston, MA), March 8, 1909, unspecified: box 222, folder 279, Race Blending, Records of the President of Harvard University, Charles W. Eliot, UAI 5.150, Harvard University Archives.

-

“Mixture of Kindred Races,” San Francisco Chronicle, March 23, 1909, unspecified: box 222, folder 279, Race Blending, Records of the President of Harvard University, Charles W. Eliot, UAI 5.150, Harvard University Archives.

-

“He makes Cupid laugh,” illustration, unknown newspaper, n.d., unspecified: box 222, folder 279, Race Blending, Records of the President of Harvard University, Charles W. Eliot, UAI 5.150, Harvard University Archives.

-

William Monroe Trotter to Charles W. Eliot, April 28,1909, unspecified: box 114, Race, 1909, Records of the President of Harvard University, Charles W. Eliot, UAI 5.150, Harvard University Archives.

-

Charles W. Eliot to William Monroe Trotter, April 30, 1909, unspecified: box 114, Race, 1909, Records of the President of Harvard University, Charles W. Eliot, UAI 5.150, Harvard University Archives.

-

Text quoted in this and the prior sentence is from Charles W. Eliot to William Monroe Trotter, April 30, 1909. In an earlier speech at the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute, Eliot explained his conviction that political and social equality are unrelated, saying: “For social equality rests on natural or instinctive likes and dislikes, affinities and repulsions, which no political institutions have ever been able to control.” See What Uplifts a Race and What Holds It Down, unspecified: box 220, folder 180, Records of the President of Harvard University, Charles W. Eliot, UAI 5.150, Harvard University Archives.

-

Text quoted in this and the prior sentence is from Charles W. Eliot to William Monroe Trotter, April 30, 1909.

-

William Monroe Trotter to Charles W. Eliot, May 1, 1909, unspecified: box 114, Race, 1909, Records of the President of Harvard University, Charles W. Eliot, UAI 5.150, Harvard University Archives.

-

Charles W. Eliot, Public opinion and sex hygiene: an address delivered at the fourth International congress on school hygiene, at Buffalo, New York, August 27th, 1913 (New York, NY: The American Federation for Sex Hygiene, 1913).

-

Paul A. Lombardo, “When Harvard Said No to Eugenics: The J. Ewing Mears Bequest, 1927,” Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 57, no. 3 (Summer 2014): 379.