Race Scientists: Louis Agassiz, John Collins Warren, and Jeffries Wyman

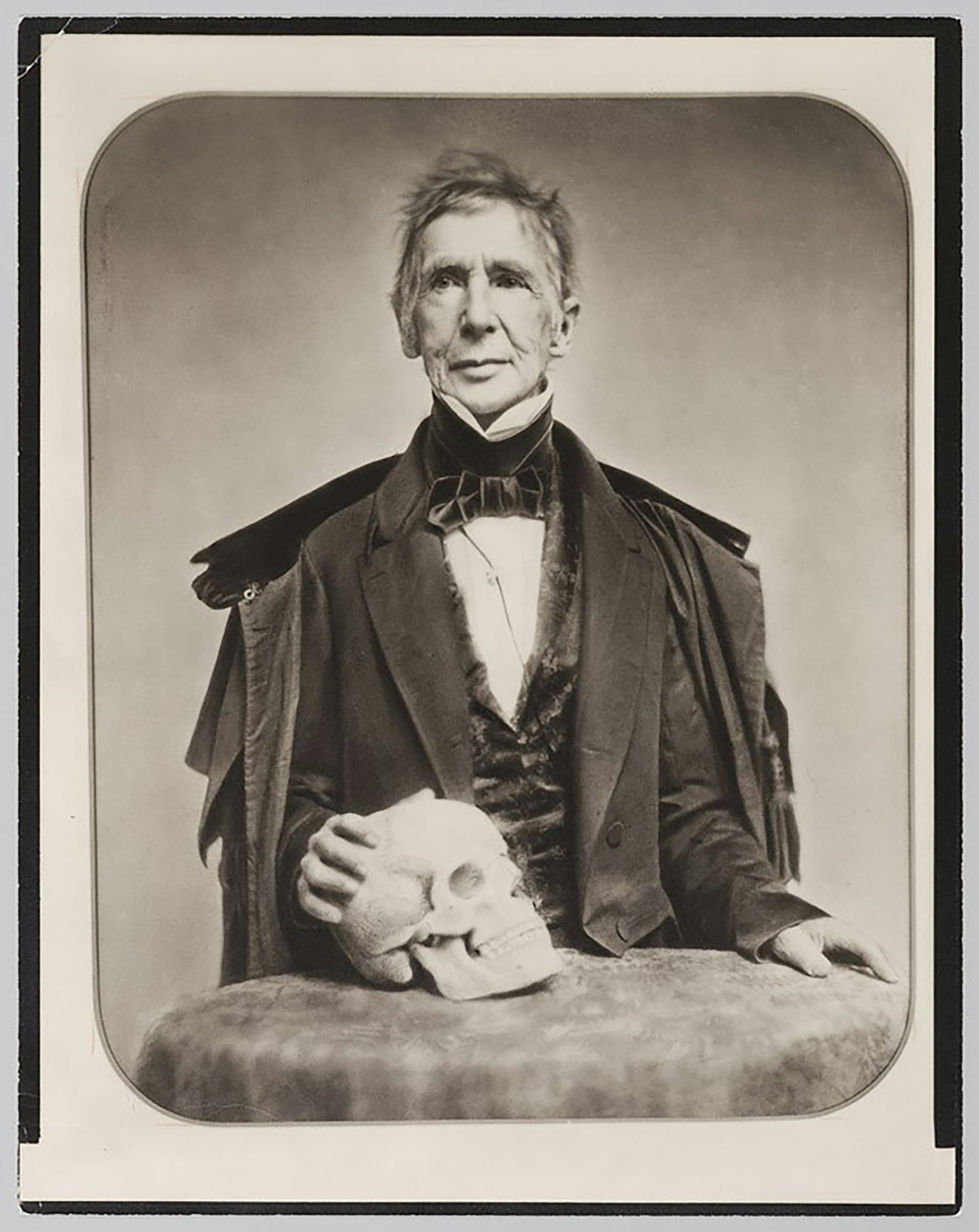

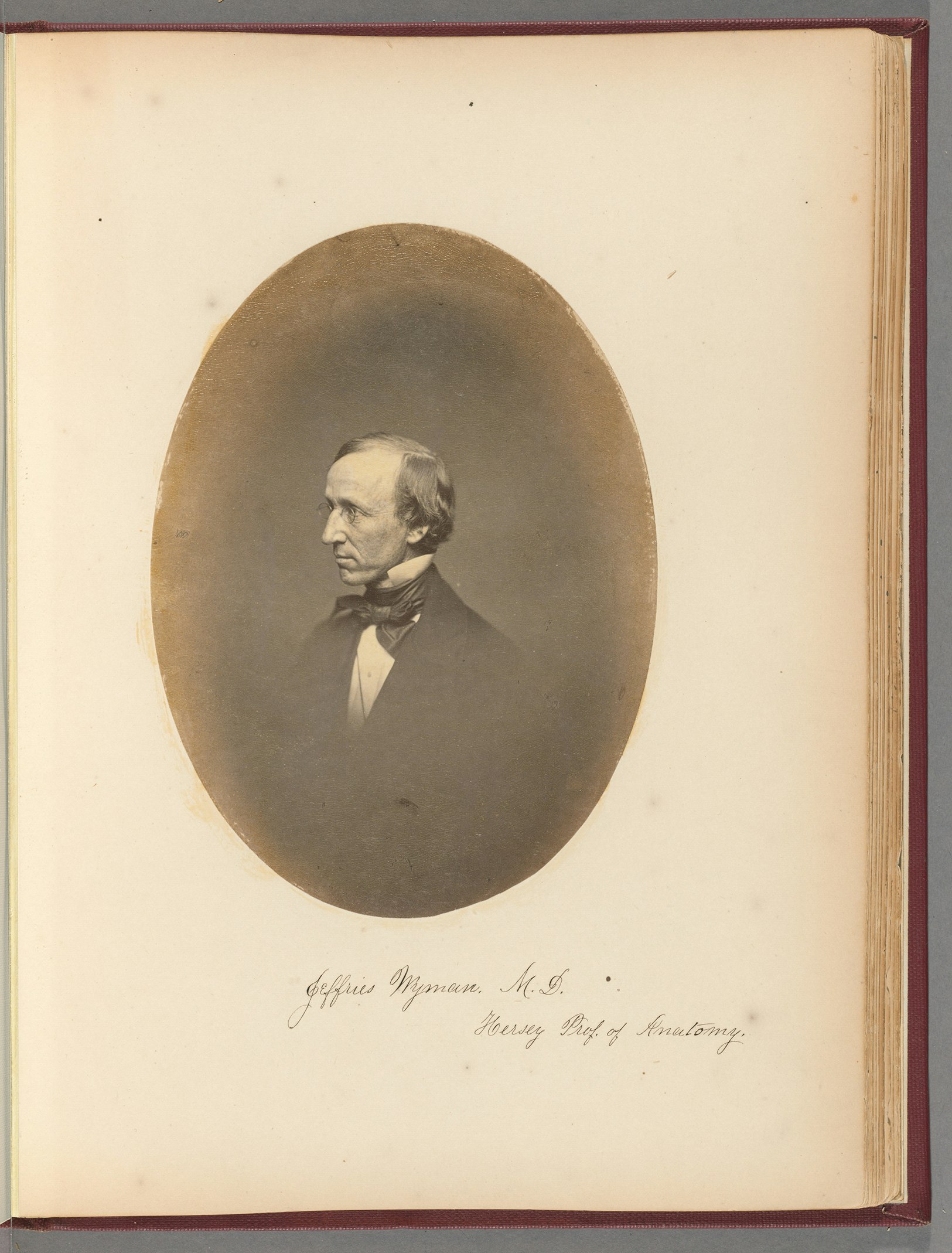

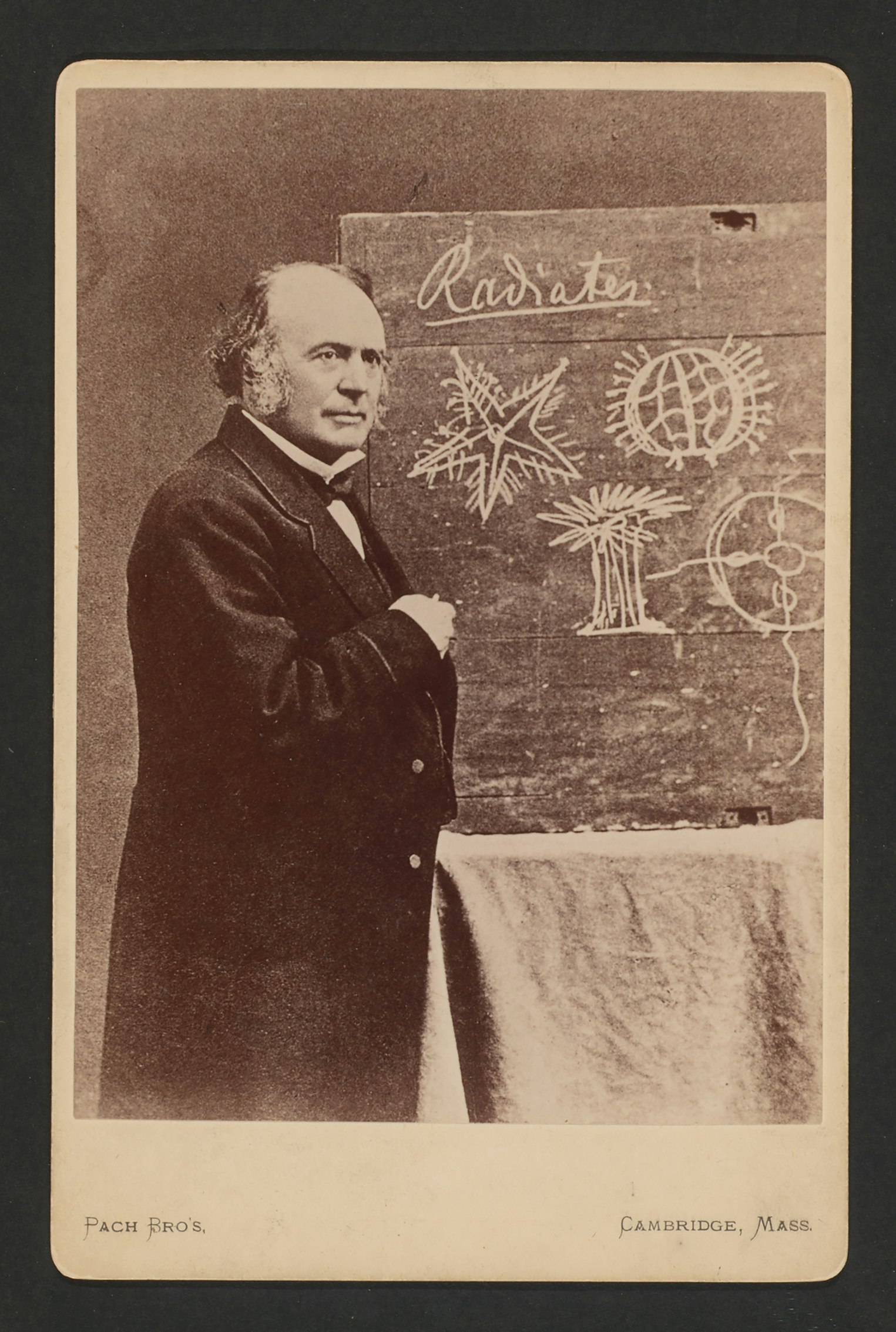

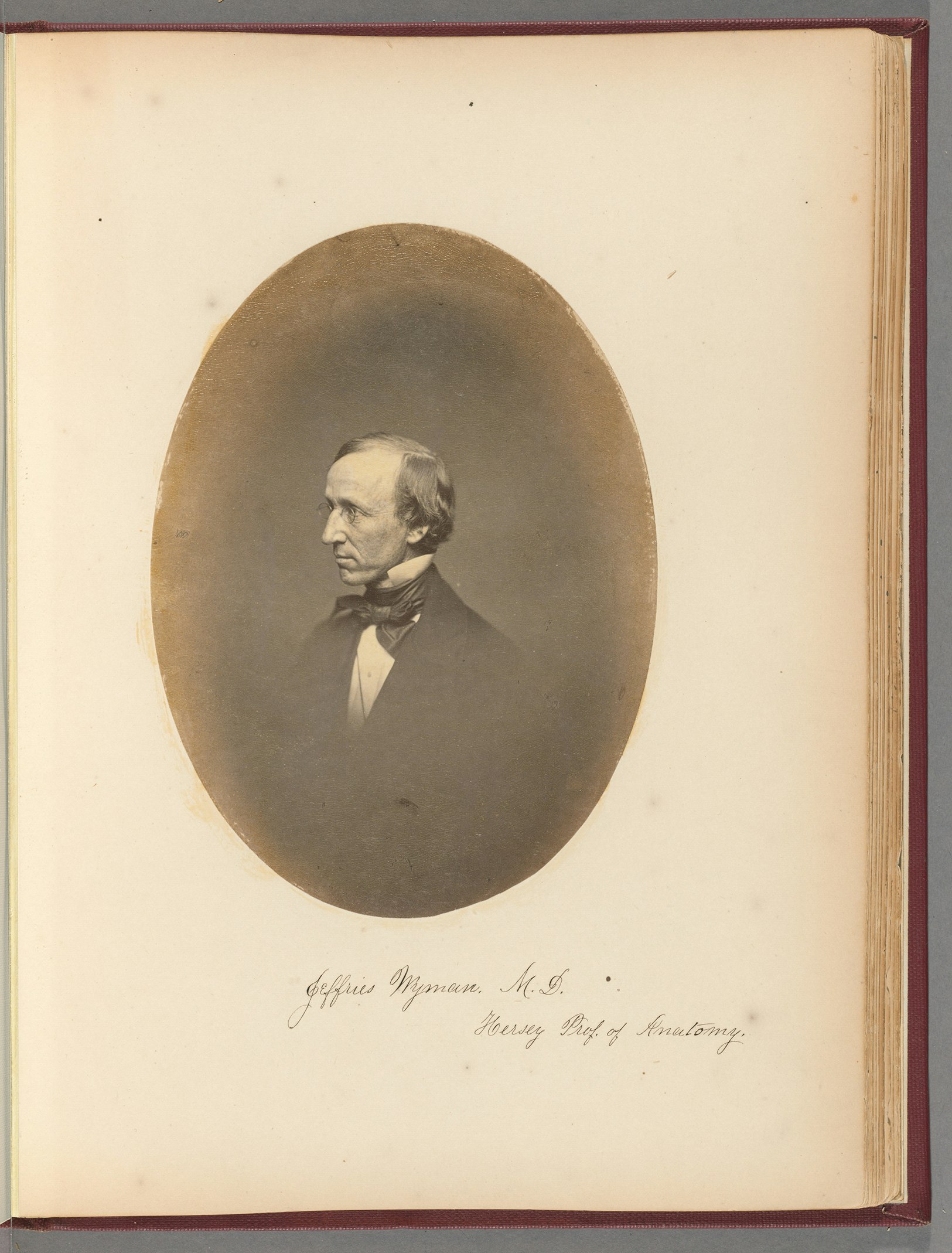

This episode took place in the context of the growth of race science at Harvard, which provided an intellectual framework to justify the exclusion and marginalization of Blacks that would endure into the 20th century. Along with Holmes, those engaging with racial difference at Harvard included John Collins Warren (AB 1797; dean, 1816–1819; faculty, 1809–1856), the son of one of the Medical School’s cofounders and himself the first dean of the faculty of medicine, and Holmes’s contemporaries Jeffries Wyman (faculty, 1838–1840 and 1847–1874) and Louis Agassiz (hon. 1848; faculty, 1847–1873). No one was as influential in this area as the renowned Swiss-born scientist Agassiz, yet each of these men—Warren, Wyman, and Agassiz—left powerful legacies on Harvard’s campus and in the wider world.

Agassiz and Wyman both joined Harvard at a time of institution-building, Agassiz at the new Lawrence Scientific School and Wyman, like Holmes, at the Medical School.Go to footnote 396 detail Wyman succeeded Warren as a professor of anatomy, but Warren remained active in the University until his death in 1856. These three men, as colleagues and collaborators, were instrumental in the creation of major Harvard institutions.

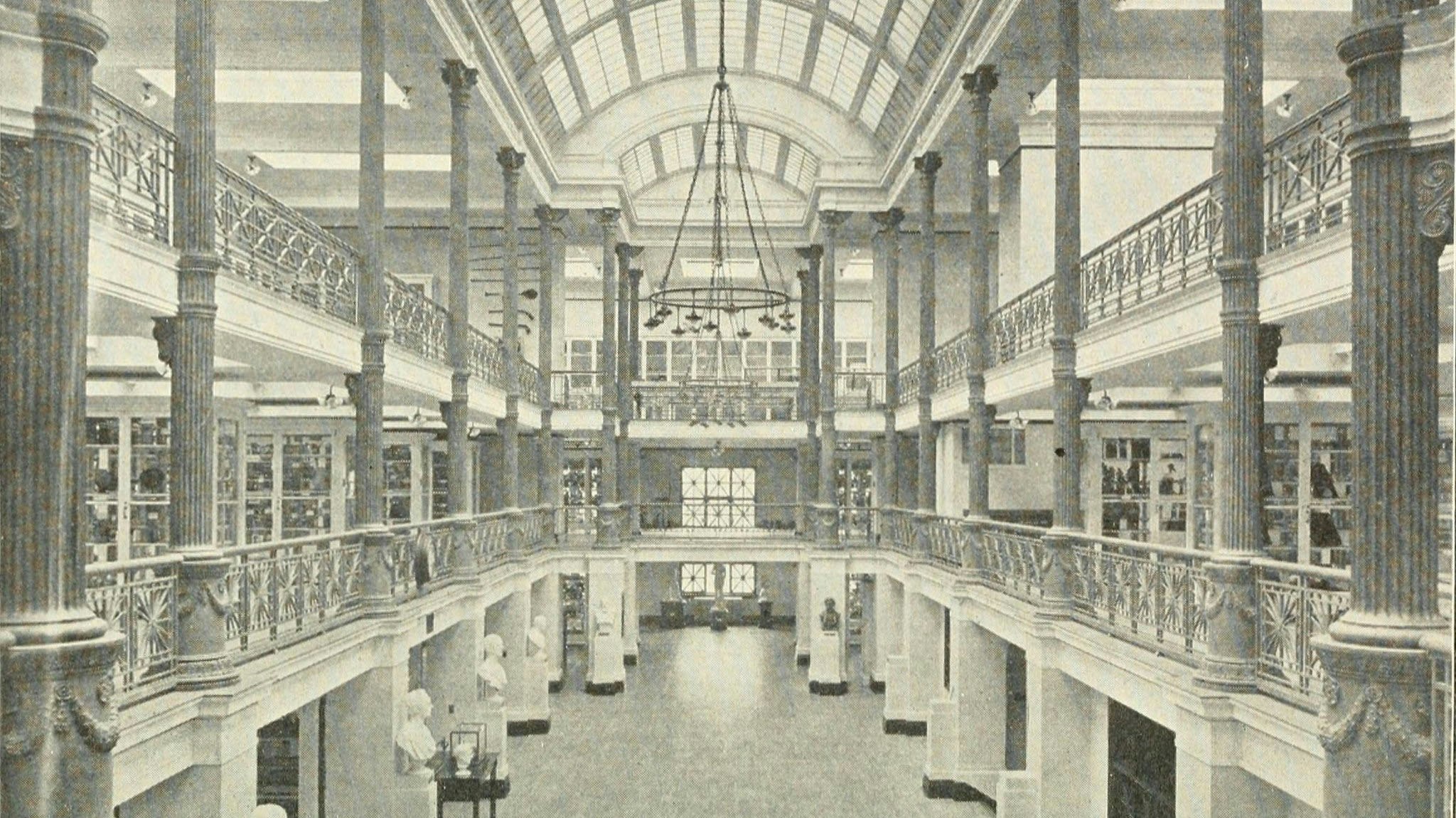

The Warren Anatomical Museum, now housed within Harvard Medical School’s Countway Library, was established when Warren donated his and his father’s vast collections of “pathological and other specimens” to Harvard, including human skulls and “phrenological” casts.Go to footnote 397 detail Wyman led the creation of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, where he served as inaugural curator. And Agassiz established and served as the first curator of the Museum of Comparative Zoology.Go to footnote 398 detail

The Agassiz name remains visible across Harvard’s campus and the City of Cambridge. Louis, who served as professor of zoology and geology from 1847 to 1873 and as curator of the Museum of Comparative Zoology from its founding in 1862 until 1873,Go to footnote 399 detail is the most well-known member of the Agassiz family. Yet the memorials that remain are generally named for his wife, Elizabeth Cary Agassiz (for instance a professorship, a gate in Radcliffe Yard, and Elizabeth Cary Agassiz House, home of the Harvard College Admissions Visitor Center), or for his son, Alexander Agassiz (namesake of Harvard professorships).

Elizabeth is credited as coauthor of A Journey in Brazil (1868), a travelogue about their yearlong scientific expedition in the country, discussed below.Go to footnote 400 detail She also left her own powerful mark at Harvard: in 1879, she was among a group of reformers who founded the Harvard Annex, where women could receive instruction from Harvard faculty. The Annex was soon incorporated as the Society for the Collegiate Instruction of Women, and in 1894, it was chartered as Radcliffe College. Elizabeth served as the first president of Radcliffe College and was a pioneering leader in the history of women’s education.Go to footnote 401 detail Alexander, an engineer and investor in copper mining as well as a scholar of natural history, also worked closely with his father. He handled much of Louis’s correspondence in the final years of his life and succeeded Louis as curator of the Museum of Comparative Zoology in 1874.Go to footnote 402 detail Alexander donated substantial sums to several organizations in the final years of his life, including more than $200,000 to the museum to support research, publications, and the professorships that still bear his name.Go to footnote 403 detail

Agassiz’s Early Career and the Zealy Daguerreotypes

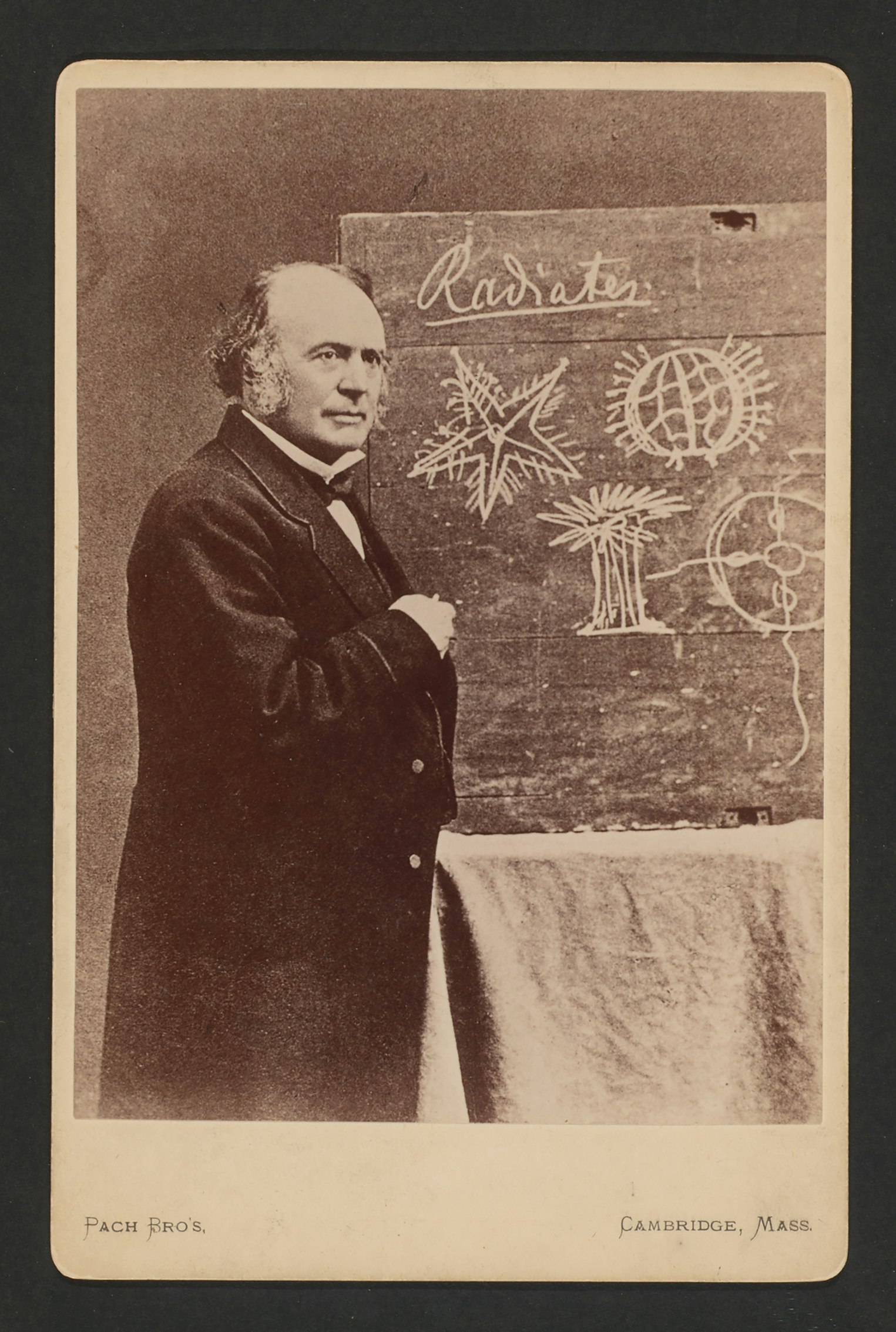

Louis Agassiz’s journey to Harvard began when he was invited to deliver the Lowell Institute’s Lowell Lectures.Go to footnote 404 detail While the institute was not affiliated with Harvard, it was a forum that attracted many esteemed Harvard affiliates as lecturers and guests. Agassiz’s 1845 invitation came on the recommendation of the German naturalist Alexander von Humboldt, who was able to secure funding for Agassiz’s Atlantic crossing through his position as an advisor to the king of Prussia.Go to footnote 405 detail Agassiz was by then a prominent naturalist, known in Europe’s scientific circles for his work on glaciation and the classification of ancient fish species.Go to footnote 406 detail In this work, he was part of a movement toward classifying flora and fauna according to geographic origin, building upon Carl Linnaeus’s universal system of classification.Go to footnote 407 detail Naturalists of the era were known for their splendid depictions of nature and often went on scientific expeditions in the Americas to collect specimens for their research. Their preoccupation with nature also extended to the classification of humans “into a single natural hierarchy of difference and similarity,” organized under the rubric of race.Go to footnote 408 detail

The field of anthropology emerged in this context to study diversity among human groups as a function of visible racial difference.Go to footnote 409 detail Medical scientists contributed to the field’s growth by investigating relationships among racial typology, geography, and disease. Phrenology, which related the shape and size of the cranium to intellectual and moral faculties, became a popular racial scientific field; craniometry, the measurement and dissection of human skulls, was its primary method. By the 19th century, race science had become a global enterprise,Go to footnote 410 detail and Agassiz was fully immersed when he arrived in the United States in the fall of 1846.

Among the first things Agassiz did in America was to view the prominent anatomist Samuel George Morton’s skull collection in Philadelphia,Go to footnote 411 detail an early stop on his tour of the scientific community in the United States, which warmly embraced him.Go to footnote 412 detail Agassiz spent “four hours in contemplation” of the skulls of Native Americans and received a personal copy of Morton’s Crania Americana, inscribed by the author. In a letter to his mother, Agassiz wrote that Morton’s “collection alone merits a trip to the United States.”Go to footnote 413 detail He also reflected on his first encounter with African Americans:Go to footnote 414 detail “It is impossible for me to repress the feeling that they are not the same blood as us.”Go to footnote 415 detail

At this time, the United States was on the verge of establishing its own scientific institutions and schools of thought independent from those of Europe. Polygenism—which proposed not only a hierarchy of races but also separate creations of different races—was “an important agent in this transformation” because it was “of largely American origin” yet acquired authority from European scientists who had long pursued scientific theories of racial difference themselves.Go to footnote 416 detail Agassiz understood the importance of this moment in the nation’s intellectual life and saw an opportunity. Some two years later, now a member of the Harvard faculty and building a celebrity status matched by few other scientists, he declared to the Boston Society of Natural History that American scientists “had been obliged to look up to Europe as our leader and guide in this pursuit,” but “a short period of persevering labor … would place America in the position hitherto occupied by the Old World.”Go to footnote 417 detail

Agassiz first formally articulated his embrace of polygenism at an 1850 meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) in Charleston, South Carolina.Go to footnote 418 detail In an essay published soon thereafter, he set out to disprove the “prevailing opinion, which ascribes to all living beings upon earth one common centre of origin, from which it is supposed they, in the course of time, spread over wider and wider areas, till they finally came into their present distribution.”Go to footnote 419 detail His primary objective was “to show that there is no such statement in the book of Genesis: that this doctrine … is of very modern invention, and that it can be traced back for scarcely more than a century in the records of our science.”Go to footnote 420 detail In another essay, he concluded that Blacks were at the bottom of a racial hierarchy ordained in nature and contended that “there has never been a regulated society of black men developed” in Africa, suggesting a “peculiar apathy … to the advantages afforded by civilized society.”Go to footnote 421 detail

Such views were controversial even then. The first half of the 19th century represented a period of hardening of race as a scientific concept in the United States, at the height of debate over “monogenesis” versus “polygenesis,” or the single versus separate origins of races.Go to footnote 422 detail Monogenists, who believed in a single human creation, immediately criticized Agassiz’s arguments. Writing to her then fiancé, Elizabeth Cary noted the opposition building to his ideas: “Some of the Church people are out upon you in the papers, for your disrespect of Adam as the common father of mankind.”Go to footnote 423 detail Congress was also, at this time, debating the Fugitive Slave Act, the passage of which would galvanize antislavery sentiment in New England.Go to footnote 424 detail Agassiz flatly denied that his research had bearing on the fraught political question of slavery,Go to footnote 425 detail although he asserted that it was “mock-philanthropy and mock-philosophy to assume that all races have the same abilities, enjoy the same powers, and show the same natural dispositions, and that in consequence of this equality they are entitled to the same position in human society.”Go to footnote 426 detail

Agassiz was celebrated in the South, where he was invited to the homes of prominent slaveholders and gave iterations of his 1850 AAAS lecture.Go to footnote 427 detail Some of these visits were arranged by a local paleontologist and physician who welcomed Agassiz to plantations in Columbia, South Carolina, to examine enslaved Africans as live research specimens. Following Agassiz’s examination, Joseph T. Zealy made daguerreotype images of seven men and women for Agassiz’s further study: Delia, Jack, Renty, Drana, Jem, Alfred, and Fassena.Go to footnote 428 detail In so doing, Zealy created what the New York Times described in 2020 as “some of history’s cruelest, most contentious images—the first photographs, it is believed, of enslaved human beings.”Go to footnote 429 detail

It was more than a century before historians retraced the identities and origins of the individuals represented in Agassiz’s daguerreotypes. We now know that Delia, Renty’s daughter, was an enslaved girl from Columbia, and that Jack was Drana’s father. Fassena, noted in the daguerreotype as a carpenter, was Mandingo, originally from modern southern Mali and Northern Guinea. They are each pictured nude or nearly so.Go to footnote 430 detail

Agassiz returned to the South in 1851–1852 with his new wife, Elizabeth, who would become his frequent collaborator. The collection of research specimens—including human specimens—remained his focus.Go to footnote 431 detail In an 1852 letter, he begged pardon for his delayed arrival at his next destination, explaining that he “found … an excellent opportunity of examining the negros, of which I must avail myself.”Go to footnote 432 detail

Agassiz’s wide-ranging specimen collections were a celebrated part of life and learning at Harvard. In an 1850 report to the overseers, University President Jared Sparks highlighted Agassiz’s, Wyman’s, and the University’s collections. Some of these were on display in Holden Chapel, used by the Medical School as a lecture hall and then assigned to the new Lawrence Scientific School, including a “curious collection of casts of skulls … which was purchased and presented to the University several years ago.”Go to footnote 433 detail

Wyman, Agassiz, and Sturmann

In September of 1860, “an extraordinary importation from South Africa” arrived in Boston—five human beings described as “a Fuigo, a Zulu, a Kaffir, a Bushman, and a Hottentot, all sons of the forests and the desert who have hitherto lived the life of savages.”Go to footnote 434 detail These living “specimens,” had been acquired by the owners of the Boston Aquarial and Zoological Gardens for public exhibition. The announcement promised a one-of-a-kind experience, “seeing these specimens of human nature in a savage condition just as they appear in their native forests and wilds”—including “monkey tricks.” Their names were given as Machiado, Macormo, Macuolo, Quaggu, and Sturmann.Go to footnote 435 detail

Advertisements described how the museum space was divided into two departments: the aquarial and the zoological.Go to footnote 436 detail The Africans were to be displayed alongside an assortment of “rare and beautiful animals and birds” including seals, kangaroos, and “Serpents.”Go to footnote 437 detail “[R]efined and intellectual” ticketholders were promised performances of savagery on a regular schedule:

They will appear through the day, CLAD IN THEIR NATIVE DRESSES OF SKINS, ORNAMENTED WITH BEADS, FEATHERS AND PORCUPINE QUILLS, and every evening will go through the WAR, LOVE and FESTIVE DANCES,—(armed with their SPEARS, CLUBS, SHELLS, AND OTHER WEAPONS OF WAR AND OF THE CHASE,) and will also SING the NATIONAL SONGS of their SEVERAL TRIBES.Go to footnote 438 detail

The museum’s owners created a scholarly veneer by commissioning a detailed pamphlet purporting to describe “the early life of each individual specimen of the nomadic tribes.”Go to footnote 439 detail And Agassiz lent his scientific authority to the proceedings, addressing an inaugural gala on October 4, 1860.Go to footnote 440 detail

Three months later, when the popular showman P. T. Barnum exhibited the Africans in New York City, public outcry over the questionable nature of their “importation” prompted him to print a statement from Agassiz in local newspapers. Agassiz “testified” that they were not enslaved but “were shipped with the knowledge and consent of the local authorities,” and that “nothing was done in securing them that would be objectionable either in a moral point of view or with reference to the laws of nations.”Go to footnote 441 detail He did not identify these “local authorities,” nor did he address the consent of Machiado, Macormo, Macuolo, Quaggu, and Sturmann themselves.

One of the five, Sturmann, took his own life on April 28, 1861, after more than six months on display.Go to footnote 442 detail The Boston Evening Transcript announced his death in a brief editorial:

The young Hottentot at the Aquarial Gardens, yesterday terminated his life by hanging. He was seventeen years of age and used to drive a wagon at Port Natal. For several days he was noticed to act strangely, and, just before the commission of the fatal act, conveyed from the room, where he and his four companions domesticated, nearly every moveable article, in accordance with the practice of all suicides among his people. The other Africans at the Gardens are deeply affected by the death of their companion.Go to footnote 443 detail

Regardless of their distress, Machiado, Macormo, Macuolo, and Quaggu were “again on exhibition” on April 30.Go to footnote 444 detail

Sturmann’s time as an object of study in the service of race science was only beginning: Wyman, who had met Sturmann while he was on display, dissected the teenager’s body at Harvard, ultimately publishing his observations in an 1865 issue of the journal the Anthropological Review.Go to footnote 445 detail He took extensive measurements and compared them to those of a chimpanzee, a gorilla, and two Europeans. In a protracted discussion of Sturmann’s pelvis, he noted that in some respects it came “nearer to that of the anthropoids [apes] than of the Caucasians”Go to footnote 446 detail but concluded it “belonged to the human family.”Go to footnote 447 detail

Ultimately, Sturmann’s remains were recorded in the catalog of the Warren Anatomical Museum:

Item # 3237 cast of the head of a native Hottentot. The boy was seventeen years old, had been on exhibition for several months in this city; and finally hung himself. His skeleton is in the Museum of Comparative Zoology, at Cambridge, 1861.Go to footnote 448 detail

The casts of Sturmann’s head remain in Harvard’s collections.

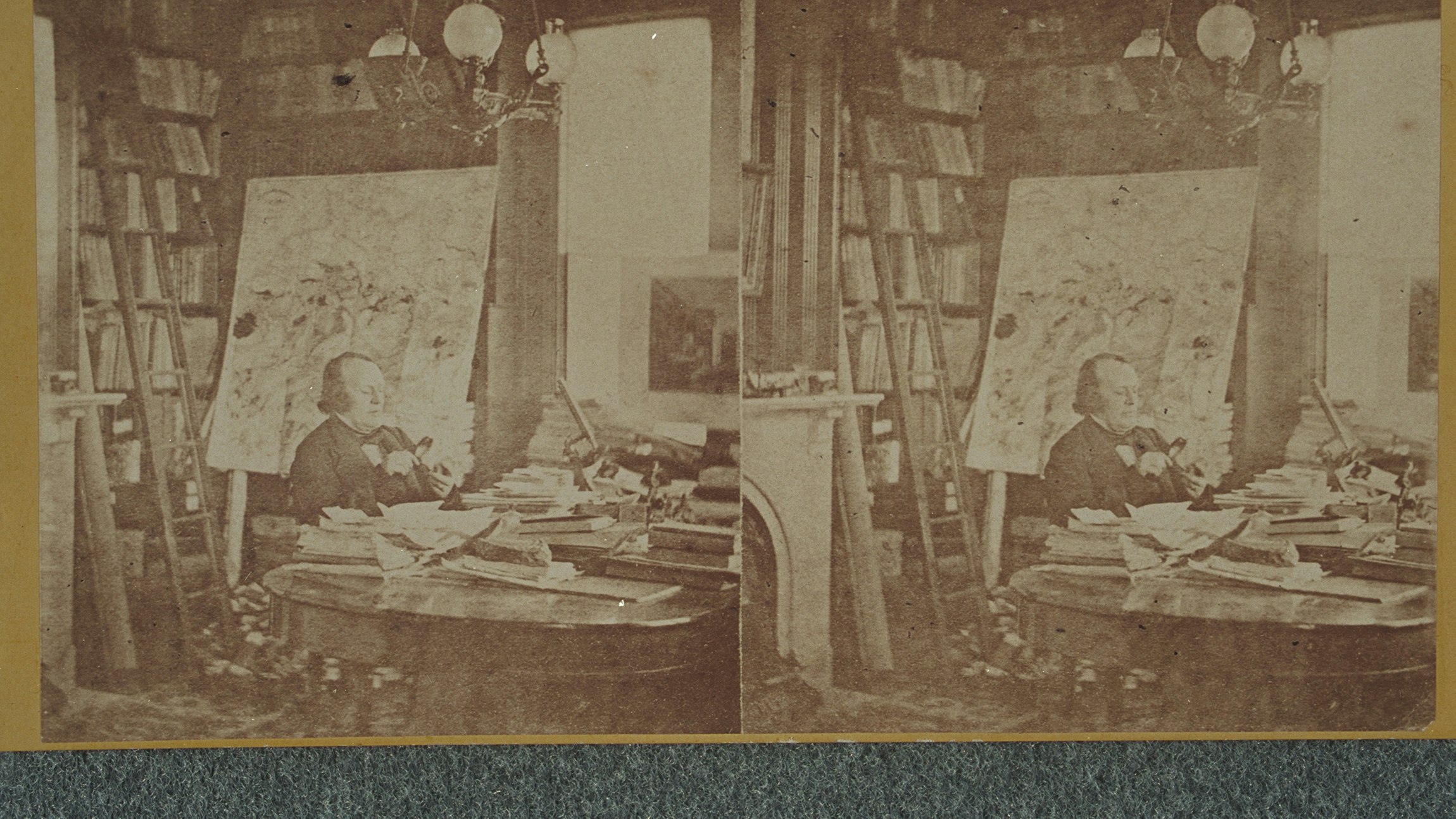

Global Collecting and the Brazil Expedition

Over nearly three decades, Agassiz also engaged colleagues across the United States and around the world, especially in the Caribbean and Latin America, to collect and classify the natural world for what would become the Museum of Comparative Zoology.Go to footnote 449 detail He instructed his collectors—including patrons, friends, readers, and lecture audiences—to send him animals of all kinds from across New England, the United States, and the world.Go to footnote 450 detail His aim was to endow the United States with a museum that would rival the best collections in Europe. Agassiz initially acquired and stored most of the collection at his own cost, raising funds to support the effort from private donors, including Elizabeth Cary Agassiz’s connections among the Boston elite.Go to footnote 451 detail

The search for specimens motivated Agassiz to organize his expedition to Brazil in 1865, in the midst of the Civil War. Polygenist ideas were losing favor following the publication of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species in 1859, and Agassiz identified Brazil as a prime location to continue his research and defend his claims.Go to footnote 452 detail In April 1865, with the support of a Boston financier,Go to footnote 453 detail Agassiz left for Brazil accompanied by Elizabeth and several Harvard students—including William James,Go to footnote 454 detail who would become an influential Harvard psychologist. Meanwhile Alexander Agassiz, now a naturalist in his own right and directly involved in his father’s work, assumed responsibility for the museum and handled Louis’s correspondence, including discussions of the procurement of human remains from South America.Go to footnote 455 detail

Because of the country’s racial diversity and its significant mixed-race population, Brazil had particular significance for Agassiz and other natural scientists of the 19th century.Go to footnote 456 detail In fact, race scientists had long identified Brazil as the embodiment of the dangers of race mixture, which they argued had produced a population that doomed the nation to backwardness.Go to footnote 457 detail Race mixture was Agassiz’s focus when he commissioned a new set of photographs of Brazilian enslaved and free people. Agassiz personally oversaw the production of these images, which were taken by a local photographer and a Harvard student assistant.Go to footnote 458 detail The photographs likely were staged in the courtyard of the house in Brazil where Louis and Elizabeth had at one point resided with the research crew.Go to footnote 459 detail

Louis and Elizabeth cowrote A Journey in Brazil, published in 1868, which documented the expedition and presented their findings to a general audience in the travel narrative genre of the time. In the book’s preface, Louis specifically acknowledged the important role his wife played in the endeavor:

Partly for the entertainment of her friends, partly with the idea that I might make some use of it in knitting together the scientific reports of my journey by a thread of narrative, Mrs. Agassiz began this diary. I soon fell into the habit of giving her daily the more general results of my scientific observations, knowing that she would allow nothing to be lost which was worth preserving.Go to footnote 460 detail

Elizabeth’s own correspondence confirms her deep involvement in writing and editing the manuscript.Go to footnote 461 detail Given this, it is interesting to note that the book remains silent about the Brazil photographs, even as it provides detailed depictions of other episodes, including Louis’s sketch of their house maid. Elizabeth is also thought to have expunged from other publications Louis’s most flagrantly racist views.Go to footnote 462 detail

It is unclear whether the omission of the photographs reflects Elizabeth’s discomfort with Louis’s production of the images, all nude or seminude, her effort to safeguard Louis’s reputation, or some other motivation. Whatever the reason, these omissions underscore Elizabeth’s active participation in the expedition and publication. It is also evident from her work on A Journey in Brazil that she accepted prevailing racial hierarchies and stereotypes. For example, one passage in the book describes a gathering of enslaved people that Elizabeth and the crew witnessed while Louis was elsewhere:

The dance and the song had, like the amusements of the negroes in all lands, an endless monotonous repetition. Looking at their half-naked figures and unintelligent faces, the question arose, so constantly suggested when we come in contact with this race, “What will they do with this great gift of freedom?” The only corrective for the half doubt is to consider the whites side by side with them: whatever one may think of the condition of slavery for the blacks, there can be no question as to its evil effects on their masters.Go to footnote 463 detail

Both Louis and Elizabeth were also interested in educational reform, so it is not surprising that they took time to observe the state of education across Brazil in the course of their travels. In one striking passage, they connect the deficits they perceive in Brazilians’ education with the close contact between enslavers and the enslaved in private homes:

Behind all defects in methods of instruction, there lies a fault of domestic education, to be lamented throughout Brazil. This is the constant association with black servants, and, worse still, with negro children. … Whether the low and vicious habits of the negroes are the result of slavery or not, they cannot be denied; and it is singular to see persons, otherwise careful and conscientious about their children, allowing them to live in the constant companionship of their blacks. … It shows how blind we may become, by custom, to the most palpable dangers.Go to footnote 464 detail

A complicated figure in her own right, some 11 years after the publication of A Journey in Brazil—and 6 years after her husband’s death—Elizabeth played a critically important role in promoting educational access for women through the Harvard Annex, later Radcliffe College. Notably, and notwithstanding the racial prejudices she entertained while working alongside Louis in Brazil, Radcliffe College admitted and graduated Alberta Virginia Scott, its first black alumna, as part of its first graduating class in 1898, during Elizabeth’s tenure as president (1882–1899).Go to footnote 465 detail

Footnotes

-

Harvard University, Quinquennial Catalogue, 1636-1915, 34, 111.

-

Jackson, Warren Anatomical Museum, iii, v.

-

Harvard University, Quinquennial Catalogue, 1636-1890, 32.

-

Harvard University, Quinquennial Catalogue, 1636-1915, 34.

-

Louis Agassiz and Elizabeth Cary Agassiz, A Journey in Brazil (Boston, MA: Ticknor and Fields, 1868), https://books.google.com/books?id=TNo8AAAAcAAJ.

-

“Radcliffe: From College to Institute,” Harvard Radcliffe Institute, accessed August 16, 2021, https://www.radcliffe.harvard.edu/about-the-institute/history.

-

Harvard University, Quinquennial Catalogue, 1636-1890, 32.

-

Will of Alexander Agassiz, Probate Record Books (1900-1916), and Probate Docket Books (1901-1916), Suffolk County, Massachusetts, Probate Record Book, vol. 960-970, 1910, digital images, Ancestry.com, accessed February 8, 2022.

Alexander’s will also designates bequests of books and scientific apparatus to the Lawrence Scientific School and various museums at Harvard, as well as $50,000 for the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in Boston (now Cambridge) and $50,000 for the National Academy of Sciences at Washington, DC.

-

The Lowell Institute was founded in 1846 as an educational institution in Boston. It was endowed by a substantial bequest from John Lowell, Jr. to support the Institute’s activities, including free public lectures by experts. “Lowell Institute,” The Boston Recorder 31, no. 29 (July 16, 1846): 114. See also Margaret W. Rossiter, “Benjamin Silliman and the Lowell Institute: The Popularization of Science in Nineteenth-Century America,” The New England Quarterly 44, no. 4 (1971): 602–626.

-

Irmscher, Louis Agassiz, 80. Agassiz was already well known among Boston and Harvard scientists associated with the Boston Society of Natural History, where Jeffries Wyman referenced Agassiz’s work at the society’s February 1843 meeting; see, Boston Society of Natural History, Proceedings of the Boston Society of Natural History. Boston etc.: Boston Society of Natural History, 1841–1844, vol. 1, 100.

-

Irmscher, Louis Agassiz, 44-51.

-

Phillip Sloan, “The Gaze of Natural History,” chap. 5 in Inventing Human Science: Eighteenth-Century Domains, ed. Christopher Fox, Roy Porter, and Robert Wokler (Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press, 1995), 112-151; Mary P. Winsor, Reading the Shape of Nature: Comparative Zoology at the Agassiz Museum (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1991).

-

Nancy Stepan, Picturing Tropical Nature (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2001), 16.

-

Stepan, Picturing Tropical Nature, 13-18.

-

James Poskett, Materials of the Mind: Phrenology, Race, and the Global History of Science, 1815-1920 (Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press, 2019), 3-13.

-

Today, the Morton Cranial Collection is held by the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaelogy and Anthropology. In 2020, in response to student protests, the collection was removed from public display. In 2021, the university announced that it was beginning a process of repatriating or reburying the remains of the individuals in the collection. See Christopher D. E. Willoughby, “Medicine, Racism, and the Legacies of the Morton Skull Collection,” History of Anthropology Review 45 (2021), https://histanthro.org/news/observations/medicine-racism-and-the-legacies-of-the-morton-skull-collection/, and Jill DiSanto, “Penn Museum Announces the repatriation of the Morton Cranial Collection,” Penn Today, April 13, 2021, https://penntoday.upenn.edu/news/penn-museum-announces-repatriation-morton-cranial-collection.

-

Brian Wallis, “Black Bodies, White Science: Louis Agassiz’s Slave Daguerreotypes,” American Art 9, no. 2 (Summer 1995): 39-61; Louis Agassiz, “Transcript of letter to R. M. Agassiz et al. [Boston], December 2, 1846,” Louis Agassiz Correspondence and Other Papers, MS Am 1419, Houghton Library, Harvard University, https://iiif.lib.harvard.edu/manifests/view/drs:12379926$326i.

-

Agassiz, “Transcript of letter to R. M. Agassiz et al. [Boston], December 2, 1846.”

-

Agassiz visited scientists and research institutions like Yale, Columbia, and Princeton before stopping in Philadelphia where he observed the Morton skulls. His encounter with African American hotel workers occurred in Philadelphia following his meeting with Morton. Agassiz, “Transcript of letter to R. M. Agassiz et al. [Boston], December 2, 1846,” esp. seq. 335–336. See also Stephen Jay Gould, The Mismeasure of Man, revised and expanded ed. (New York: NY: W.W. Norton & Company, 1996), 76–77.

-

Agassiz, “Transcript of letter to R. M. Agassiz et al. [Boston], December 2, 1846,” seq. 335–336; see Gould, Mismeasure of Man, 76–77.

-

Gould, Mismeasure of Man, 74.

-

Proceedings of the Boston Society of Natural History, vol. 3, 1848-1851 (Cambridge, MA: Printed for the Society by Bolles and Houghton, 1851), 36-37.

-

Molly Rogers, Delia’s Tears: Race, Science, and Photography in Nineteenth-Century America (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010), 202-205.

-

Louis Agassiz, “Geographical Distribution of Animals,” The Christian Examiner and Religious Miscellany 48, no. 2, 4th ser., 13 (March 1850): 181–204, https://books.google.com/books?id=CgEZAAAAYAAJ. For the quote, see p. 181.

-

Agassiz, “Geographical Distribution of Animals,” 181.

-

Louis Agassiz, “The Diversity of the Origin of the Human Races,” The Christian Examiner and Religious Miscellany 49, no. 1, 4th ser., 14 (July 1850): 110-145, https://books.google.com/books?id=XwEZAAAAYAAJ. For the quote, see p. 143.

-

Scott Podolsky and colleagues at Harvard Medical School provided valuable input to the discussion of this intellectual history. See also William Stanton, The Leopard’s Spots: Scientific Attitudes toward Race in America, 1815-1859 (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1960); Thomas F. Gossett, Race: The History of an Idea in America (New York, NY: Schocken Books, 1963); Bruce Dain, A Hideous Monster of the Mind: American Race Theory in the Early Republic (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002); Ibram X. Kendi, Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America (New York, NY: Bold Type Books, 2016).

-

Elizabeth Cary Agassiz, “Letters to Louis Agassiz, 1849-1850,” Papers of Elizabeth Cabot Cary Agassiz, 1838-1920 (inclusive), 1838-1908 (bulk), A-3, 9, Schlesinger Library, Harvard Radcliffe Institute.

-

See Bosco, “Fugitive Slave Act.”

-

Agassiz, “Diversity of Origins,” 112.

-

Agassiz, “Diversity of Origins,” 142.

-

Elizabeth Cabot Cary to her mother, April 15-16, “Letters from South Carolina, Washington, New Orleans, etc., 1851-1852,” folder 10, seq. 29, Elizabeth Cary Agassiz Papers, 1838-1920, A-3, Schlesinger Library, Harvard Radcliffe Institute, https://iiif.lib.harvard.edu/manifests/view/drs:10431489$29i. See also Rogers, Delia’s Tears, 205.

-

Gregg Hecimovich, “The Life and Times of Alfred, Delia, Drana, Fassena, Jack, Jem, and Renty,” chap. 2 in To Make Their Own Way in the World: The Enduring Legacy of the Zealy Daguerreotypes, ed. Ilisa Barbash, Molly Rogers, and Deborah Willis (Cambridge, MA: Peabody Museum Press, Aperture, 2020), 106-108. See also Make Their Own Way, 279-280.

-

See the book review of Make Their Own Way, Parul Sehgal, “The First Photos of Enslaved People Raise Many Questions About the Ethics of Viewing,” New York Times, September 29, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/29/books/to-make-their-own-way-in-world-zealy-daguerreotypes.html.

-

Hecimovich, “Life and Times.”

-

In 1859, Agassiz presented his entire collection—including human remains, animal specimens, fossils, and more—to the Trustees. He estimated that he spent more than $10,000 of his own money—derived at least in part from the salary he received from the University, paid until 1855 by Abbott Lawrence and funded for some time thereafter by Lawrence’s bequest to the University—in collecting and preserving the specimens, see Museum of Comparative Zoology, Report of the Committee of the Overseers of Harvard College appointed to visit The Lawrence Scientific School during the year 1860; together with The Reports Submitted by the professors (Cambridge, MA: Welch, Bigelow, and Company, 1873), 45-46.

-

[Louis] Agassiz to Harriot Pinckney Holbrook, Monday 25, [1852?], Louis Agassiz Correspondence and Other Papers, MS Am 1419, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

-

Harvard University, Twenty-Sixth Annual Report of the President of Harvard University to the Overseers on the state of the university for the academic year 1850-1851 (Cambridge, MA: Metcalf and Company, printers to the University, 1852), 5-7, https://iiif.lib.harvard.edu/manifests/view/drs:427074869$1i.

-

“An Extraordinary Importation from South Africa,” The Boston Evening Transcript, September 28, 1860.

Christopher D. E. Willoughby provided valuable input on race science at Harvard Medical School generally and on the story of Sturmann in particular, based on research for “Skull Collecting, Medical Museums, and the International Dimensions of Racial Science,” chap. 5 in Masters of Health: Racial Science and Slavery in U.S. Medical Schools (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, forthcoming fall 2022).

-

“An Extraordinary Importation from South Africa,” The Boston Evening Transcript.

-

“Amusements – Boston Aquarial and Zoological Garden,” The Boston Evening Transcript, October 3, 1860.

-

“Amusements – The Aquarial Gardens,” The Boston Evening Transcript, October 3, 1860.

-

“Amusements – Boston Aquarial and Zoological Garden,” The Boston Evening Transcript.

-

Walter Clarence, The aborigines of South Africa, now on exhibition at the Boston Aquarial and Zoölogical Gardens in Central Court, Washington Street: giving a brief description of the southern portion of the African continent, and a sketch of the early life of each individual specimen of the nomadic tribes (Boston, MA: Printed for Cutting & Butler by J. P. Plumer, 1860).

-

“Amusements – Boston Aquarial and Zoological Garden,” The Boston Evening Transcript.

-

“Specimens of the South African Tribes,” New York Tribune, January 5, 1861; “Advertisement,” New York Herald, January 3, 1861. See also Matthew Smith Miller, “Surely his mother mourns for him: Africans on exhibition in Boston and New York, 1860-1861,” (AB thesis, Harvard University, 2011).

-

Sturmann’s name has been transcribed with a variety of different spellings. Here we are using the spelling that appears in the first Boston Evening Transcript announcement of the exhibition: “An Extraordinary Importation from South Africa.” It is likely that the names reported were not only printed inaccurately, but were in at least some cases assigned stage names.

-

“Suicide at the Aquarial Gardens,” The Boston Evening Transcript, April 29, 1861.

-

“Amusements—Boston Aquarial and Zoological Gardens,” The Boston Evening Transcript, April 30, 1861.

-

Jeffries Wyman, “Observations on the Skeleton of a Hottentot,” The Anthropological Review 3, no. 11 (October 1865): 330-335.

-

Wyman, “Observations on the Skeleton of a Hottentot,” 334.

-

Wyman, “Observations on the Skeleton of a Hottentot,” 333.

-

Jackson, Warren Anatomical Museum, 702.

-

Winsor, “‘In the Prime of His Admirable Manhood,’” chap. 1 and “‘I Have Been Disappointed in My Collaborators,’” chap. 2 in Reading the Shape of Nature; Irmscher, Louis Agassiz.

-

Louis Agassiz’s letters on the collections of specimens for the museum can be found in Alexander Agassiz, “Agassiz letter books, 1859-1910,” vol. 4, Alexander Agassiz and Louis Agassiz letters, June 18, 1866-July 30, 1868, Spec. Coll. MCZ F890, Ernst Mayr Library, Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, https://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:FMUS.MCZ:2709033.

-

In her biography of Louis, Elizabeth wrote that their marriage “connected him by the closest ties with a large family circle,” including his brother-in-law, future Harvard President Cornelius Felton (president, 1860–1862; faculty, 1832–1860; tutor, 1829–1832), quoted in Irmscher, Louis Agassiz, 278. Elizabeth was the granddaughter of wealthy merchant Thomas Handasyd Perkins (see Section III of this report), and her family ties included her namesakes, the prominent Boston (and Harvard) families the Cabots and the Carys. See “Collection Overview: Biography,” Papers of the Cabot family, 1786–2013, A-99, Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, accessed February 10, 2022, https://id.lib.harvard.edu/ead/sch00131/catalog; “Biographical Sketch,” Thomas Greaves Cary Papers, 1832–1885, accessed February 10, 2022, https://www.masshist.org/collection-guides/view/fa0339.

-

Irmscher, Louis Agassiz, 297-308.

-

Irmscher, Louis Agassiz, 297.

-

Irmscher, Louis Agassiz, 298-300.

-

“Agassiz letter books, 1859-1910,” Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University.

-

Stepan, Picturing Tropical Nature.

-

Stepan, Picturing Tropical Nature; Dain Borges, “‘Puffy, Ugly, Slothful and Inert’: Degeneration in Brazilian Social Thought, 1880-1940,” Journal of Latin American Studies 25, no. 2 (May 1993): 235-256.

-

Christoph Irmscher, “Mr. Agassiz’s ‘Photographic Saloon’,” chap. 7 in Make Their Own Way, ed. Barbash et al., 205, 208-209, 214, 226-227.

-

Agassiz and Agassiz, Journey in Brazil, 251-252; Irmscher, “Mr. Agassiz’s ‘Photographic Saloon’,” 215-216.

-

Agassiz and Agassiz, Journey in Brazil, ix-x.

-

See Elizabeth Cary Agassiz to Sallie and Emma, January 6, 1868, seq. 87, folder 17, Letters to Mrs. Cary, Sally and Emma while they were in Europe, 1867–1868, Elizabeth Cary Agassiz Papers, 1838–1920, A-3, Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, https://nrs.lib.harvard.edu/urn-3:rad.schl:2026876?n=87.

See also Irmscher, Louis Agassiz, 297: “In 1868, Elizabeth Agassiz published A Journey in Brazil, a vivid account of her husband’s research trip to Brazil … Here there was no more ventriloquizing for Agassiz. He was no longer her mask; instead, he had become her topic.”

-

Harvard biologist and historian Stephen Jay Gould, who held an Alexander Agassiz Professorship of Zoology, wrote that Elizabeth “expurgated without indication” racist passages in the collection of Louis Agassiz’s correspondence that she edited and published in 1885. Gould published many of these passages, see Mismeasure of Man, 77, quote on 79. See also Agassiz, Louis Agassiz.

Agassiz biographer Christoph Irmscher also presents evidence that Elizabeth revised her husband’s correspondence prior to publication, citing multiple letters that Louis Agassiz wrote to Samuel Gridley Howe, a member of the American Freedmen’s Inquiry Commission, in which Agassiz sought to convince Howe of the dangers of miscegenation. Irmscher, Louis Agassiz, 245-251, 390, n. 61.

-

Agassiz and Agassiz, Journey in Brazil, 49.

-

Agassiz and Agassiz, Journey in Brazil, 481.

-

Sollors et al., eds., Blacks at Harvard, 2. Scott graduated from the Cambridge Latin School in 1894. See Helen Fuller, “The Valedictory,” The Cambridge Tribune, June 30, 1894, https://cambridge.dlconsulting.com/cgi-bin/cambridge?a=d&d=Tribune18940630-01.2.29. Radcliffe was chartered as a degree-granting institution the same year. See “Radcliffe: From College to Institute,” Harvard Radcliffe Institute.