Indigenous Slavery and African Slavery

Slavery in New England began when early colonists enslaved and sold Indigenous people while dispossessing these Native peoples of the land on which they had lived for generations.Go to footnote 100 detail

In 1636, the year Harvard was founded, merchants at Marblehead built and rigged a ship, 120 tons and very fast, called Desire. That summer, the Desire set sail carrying 17 Pequot War prisoners who were to be sold as slaves in Bermuda on the instructions of John Winthrop.Go to footnote 101 detail A towering figure in early colonial history who served several terms as Governor and Lieutenant Governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, Winthrop was a member of the original “Comittee as to ye colledg at New Toune”—that is, Harvard.Go to footnote 102 detail Winthrop himself enslaved the wife of a Pequot sachem and her two children in what he seems to have regarded as an act of Christian benevolence, reciprocity for her protection of two captured English girls during the conflict.Go to footnote 103 detail

Two years later, on February 26, 1638, the Desire returned to Boston Harbor carrying cotton, tobacco, salt, and an unspecified number of enslaved Africans who had been purchased on Providence Island. The Desire was among the first American slave ships.Go to footnote 104 detail It is possible that the man known to us only as “The Moor”—who was enslaved by Harvard’s first schoolmaster, Nathaniel Eaton, and in that capacity served Harvard’s earliest students—arrived in New England aboard the Desire.Go to footnote 105 detail

Not long after, in the early 1640s, a Bermuda minister named Patrick Copeland, grateful for Winthrop’s “remembrance of us in sending 12 New England Indians to us,” began recruiting the children of wealthy Caribbean plantation owners to attend Harvard.Go to footnote 106 detail As one historian has noted, “education, like the flag, follows trade”—and many sons of West Indian planters indeed followed trade to the Massachusetts Bay Colony and Harvard.Go to footnote 107 detail

Harvard also benefited from land grants by the General Court (the colonial legislature) in 1653:

For the incouragement of Harvard Colledge and the society thereof, and for the more comfortable maintenance and provicon for the psident, ffellowes, and students thereof in time to come, this Court doth graunt unto the said society and corporation, for the ends aforesaid, two thousand acres of land wthin this jurisdiccion, not formerly graunted to any other, to be taken up in two or three places, where it may be found convenient; and to this end it is desired that the said corporation of the college doe appoint some persons in theire behalfe to finde out the places where such land may be freely taken, and to make retourne as soone as they may, that the Court may more pticcularly and expressly confirme the same.Go to footnote 108 detail

The Harvard treasurer Thomas Danforth personally selected four tracts in Rhode Island and Connecticut, territory from which the Pequot had been driven.Go to footnote 109 detail

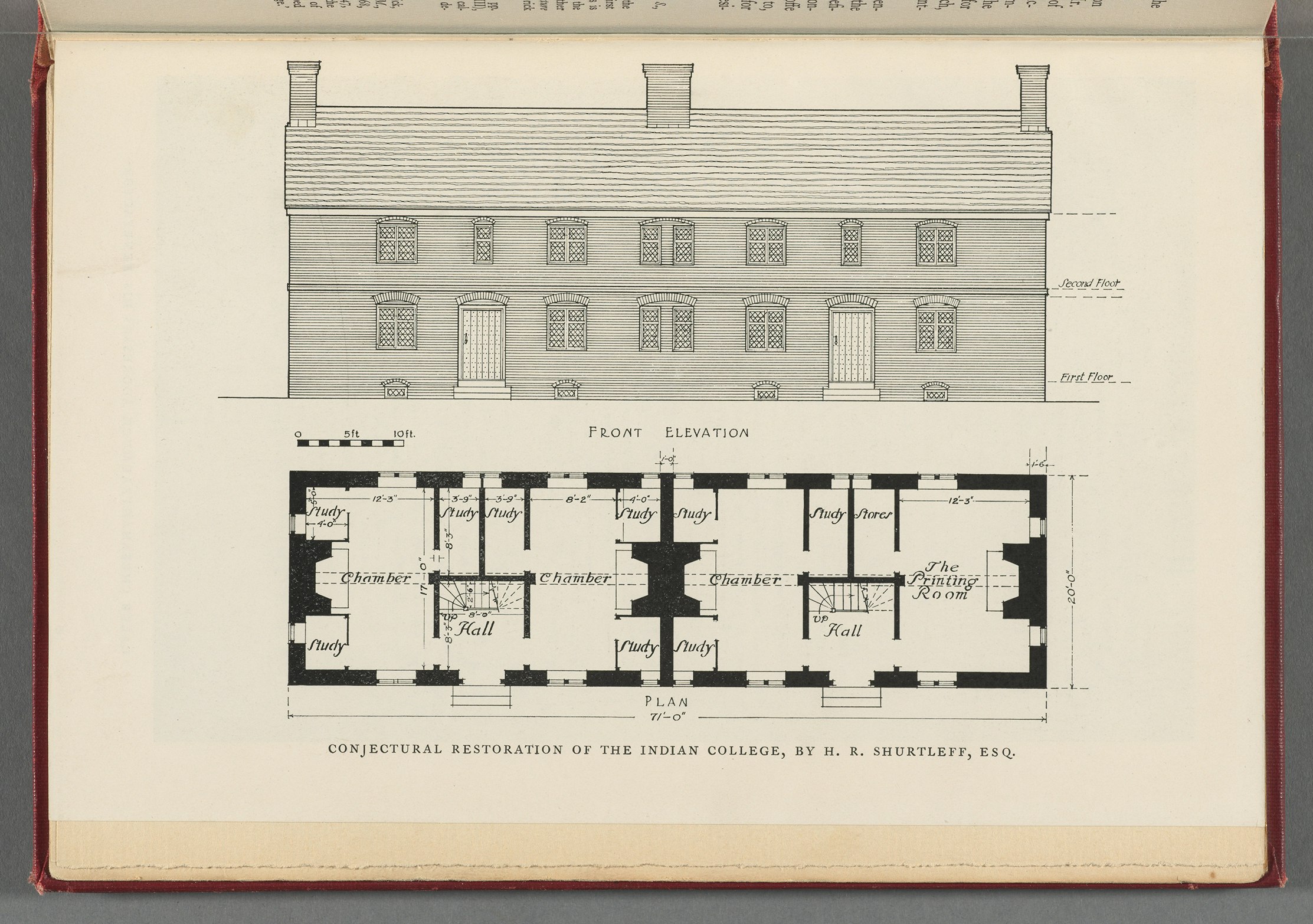

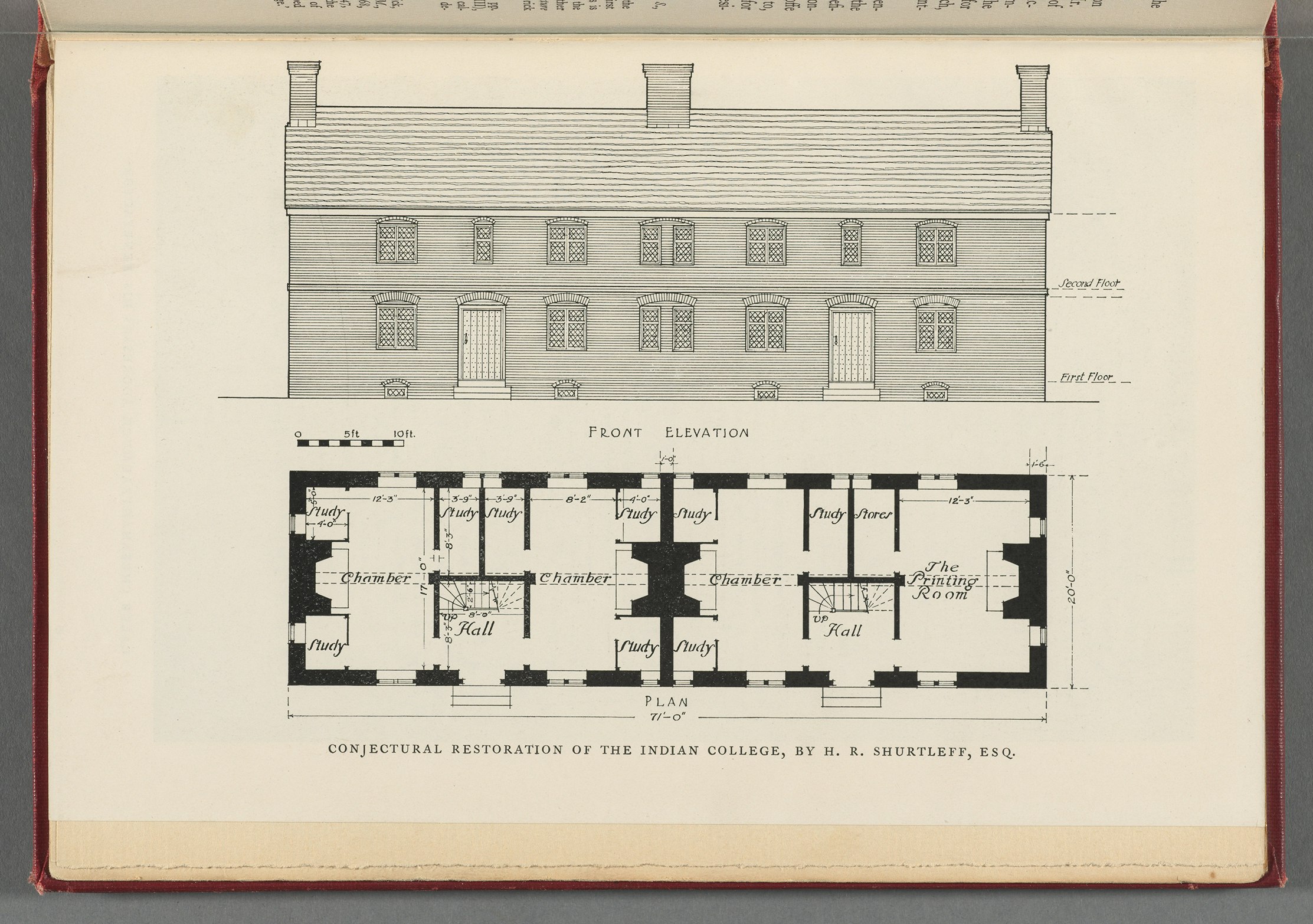

One aspect of the original mission of Harvard College was to educate (and convert) Native students alongside white classmates.Go to footnote 110 detail In the 1640s, the fledgling Colony was in the throes of an economic crisis, and the College was on the edge of collapse: Christianizing Indigenous people opened up vital new avenues of financial support. Devoted Puritans in England lined up to support the mission, and Parliament opened its coffers to aid the colonization effort by “civilizing” Natives.Go to footnote 111 detail The Charter of 1650, which has governed Harvard with few interruptions for more than 350 years, committed the institution to “the education of the English and Indian youth.”Go to footnote 112 detail The Indian College building—Harvard’s first made of brick—was constructed in 1655. Ultimately, however, Harvard enrolled only five Native students in this era, and only Caleb Cheeshahteaumuck (AB 1665) received a degree during his lifetime.Go to footnote 113 detail (Joel Iacoombs also completed the requirements of the AB degree but died in 1665 before he formally graduated. Harvard University posthumously presented Iacoombs’s degree to the Wampanoag community in 2011.Go to footnote 114 detail) By 1670, the Indian College building had been given over to the College’s printing press, and in 1698, it was dismantled, and its bricks were used to construct a new building for the use of white scholars.Go to footnote 115 detail

As the colony grew, slavery—now primarily, but not exclusively, African slavery—remained central. In the colonial era, the system that W. E. B. Du Bois would eloquently describe more than two centuries later was just beginning to take shape:

The giant forces of water and of steam were harnessed to do the world’s work, and the black workers of America bent at the bottom of a growing pyramid of commerce and industry; and they not only could not be spared, if this new economic organization was to expand, but rather they became the cause of new political demands and alignments, of new dreams of power and visions of empire. …

Black labor became the foundation stone not only of the Southern social structure, but of Northern manufacture and commerce, of the English factory system, of European commerce, of buying and selling on a world-wide scale; new cities were built on the results of black labor.Go to footnote 116 detail

The number of enslaved women, men, and children in Massachusetts, itself a small colony of some 33,000 inhabitants according to a 1675 census,Go to footnote 117 detail remained relatively low until the end of the 17th century, and enslaved people formed part of a larger world of unfree labor that also included indentured white servants.Go to footnote 118 detail In 1676, colonial administrator Edward Randolph wrote that there were “not above 200 slaves in the colony, and those are brought from Guinea and Madagascar.”Go to footnote 119 detail Four years later, Governor Simon Bradstreet told the Lords of the Committee for Trade and Foreign Plantations that “there are a very few blacks borne here, I think not above [five] or six at the most in a year.”Go to footnote 120 detail Unlike white indentured servants, who eventually left their unfree status behind, these enslaved Africans faced lifetimes of uncompensated labor, both for themselves and for their descendants.

The enslaved population of Massachusetts rose quickly after the British Parliament’s revocation of the Royal African Company’s monopoly on English trade with Africa in 1696.Go to footnote 121 detail It was also at this time that some New Englanders “began to rebel against the growth of actual slavery on New England soil.”Go to footnote 122 detail

Antislavery sentiment was not, however, at the root of resistance in this period.Go to footnote 123 detail Rather, limited opposition to slavery grew largely out of a concern about the growing presence of Black people and the effect that would have on society, fears that had gained salience in the wake of Bacon’s Rebellion in 1677. These concerns culminated in the passage in 1705 of an act “for the Better Preventing of a Spurious and Mixt Issue,” which put a prohibitive £4 tax on all slaves imported.Go to footnote 124 detail The colonial legislature also adopted other measures designed to maintain the racial balance, such as the 1709 “Act to Encourage the Importation of White Servants,” which promised payment of forty shillings per white male servant imported into the colony and extended the 1705 import tax to include enslaved Native Americans.Go to footnote 125 detail Despite such efforts, the number of enslaved people in the Massachusetts Bay Colony rose to 550 by 1708, and in 1720, Governor Samuel Shute wrote that “With respect to slaves either Negros or Indians (but most Negroes) they may be computed at about Two Thousand” alongside an English population of 94,000.Go to footnote 126 detail By the middle of the 18th century, enslaved Black people constituted the main source of bound labor in Massachusetts, outnumbering indentured servants, apprentices, and Indigenous workers.Go to footnote 127 detail

Footnotes

-

“Throughout New England before 1700, and in subregions thereafter, Native Americans represented the dominant form of nonwhite labor,” Newell, Brethren by Nature, 5. See also Warren, New England Bound and Jared Ross Hardesty, Black Lives, Native Lands, White Worlds: A History of Slavery in New England (Amherst and Boston: Bright Leaf, An Imprint of University of Massachusetts Press, 2019).

-

See Wilder, Ebony & Ivy, 25.

“The enslavement of the Pequots was the first large-scale, institutionalized distribution of people as property in the British North American colonies.” Franco Paz, “On the Edge of Freedom: The Re-enslavement of Elizabeth Watson,” MA thesis (University of Vermont, 2018), 32, accessed March 1, 2024, https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis/905/. Paz cites Greene, Negro in Colonial New England, 16, and George Henry Moore, Notes on the History of Slavery in Massachusetts (New York, NY: D. Appleton & Co., 1866), 7–8, https://books.google.com/books?id=ohsEAAAAYAAJ. See also Newell, “’David’s warre’ The Pequot War and the Origins of Slavery,” chap. 1 in, Brethren by Nature.

As several historians have noted, due to a navigational error the Pequot prisoners of war were in fact sold in the Puritan colony of Providence Island. They did not arrive in Bermuda until 1640. See Paz, “On the Edge of Freedom,” 32 n. 5, accessed March 1, 2024, https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis/905/; Newell, Brethren by Nature, 50–51; Ethel Boissevain, “Whatever Became of the New England Indians Shipped to Bermuda to be Sold as Slaves?” Man in the Northeast 21 (1981): 103–114; F. Van Wyck Mason, “Bermuda’s Pequots,” Harvard Alumni Bulletin 39 (February 26, 1937): 616–620; Karen Ordahl Kupperman, Providence Island, 1630–1641: The Other Puritan Colony (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1993).

-

John Langdon Sibley, Biographical Sketches of Graduates of Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Volume I, 1642–1658 (Cambridge, MA: Charles William Sever, University Bookstore, 1873), 1–7, https://books.google.com/books?id=SRZSAQAAMAAJ.

-

Newell, Brethren by Nature, 40–41, 79; Manegold, Ten Hills Farm, 42; Francis J. Bremer, John Winthrop: America’s Forgotten Founding Father (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003), 273. See also John Winthrop to William Bradford, Winthrop Family Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society, accessed August 27, 2021, https://www.masshist.org/publications/winthrop/index.php/view/PWF03d358.

-

George Francis Dow, Slave Ships and Slaving (Reprint, New York, NY: Dover Publications 2002), 267; George Henry Preble, “Notes on Early Ship-Building in Massachusetts,” The New-England Historical and Genealogical Register and Antiquarian Journal 25, no. 1 (1871): 17; James Kendall Hosmer, ed., Winthrop’s Journal: History of New England, 1630–1649, vol. 1, (New York, NY: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1908), 260, https://books.google.com/books?id=Iwo6FnGALocC.

-

On Eaton’s tenure as schoolmaster, see Morison, Three Centuries of Harvard, 7–10. See also Susan E. Maycock and Charles M. Sullivan, Building Old Cambridge: Architecture and Development (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2016), 8; Margery Somers Foster, Out of Smalle Beginnings: An Economic History of Harvard College in the Puritan Period (1636 to 1712) (Boston, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1962), 5–6. On “the Moor,” see John Winthrop, The History of New England from 1630 to 1649, vol. 1, ed. James Savage (Boston, MA: Little, Brown, 1853), 372–375, https://books.google.com/books?id=KIarrcIX7QAC. Winthrop’s description of the Moor was reprinted in Sibley, Biographical Sketches of Graduates, 5.

-

Patrick Copeland to John Winthrop, December 4, 1639, Papers of the Winthrop Family, vol. 4, Massachusetts Historical Society.

-

John Irwin Cooper, “The West Indies, Bermuda and American Mainland Colleges,” Jamaican Historical Review 2, no. 1 (December 1, 1949): 2.

-

Records of the Governor and Company of the Massachusetts Bay in New England, vol. 4, pt. 1, Records, 1650–1660 (Boston, MA: William White, 1854), 136, accessed February 4, 2022, https://books.google.com/books?id=XG9OAQAAMAAJ.

-

Robin Stephen McMahon, “Contested Boundaries: The Harvard Land Grants as an Archetype for Intercolonial Competition for Land,” Connecticut History Review 56, no. 2 (Fall 2017): 203–209.

-

Charter of 1650, Harvard University Archives, https://iiif.lib.harvard.edu/manifests/view/ids:6597921$1i. For a transcription, see “Harvard Charter of 1650,” Harvard Library, Harvard University, accessed February 4, 2022, https://guides.library.harvard.edu/c.php?g=880222&p=6323072; Foster, Smalle Beginnings, 2.

-

Lisa Brooks, Our Beloved Kin: A New History of King Philip’s War (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2018), 81–82, 97–99; Foster, Smalle Beginnings, 107–109, 117–118.

-

Charter of 1650, Harvard University Archives.

-

Brooks, Our Beloved Kin, 102–106. See also “Digging Veritas - The Indian College,” Peabody Museum of Archaeology & Ethnology, Harvard University, accessed January 25, 2022, https://peabody.harvard.edu/galleries/digging-veritas-indian-college.

-

“A Degree Delivered: Harvard honors Native American who completed course work in 1665,” Harvard Gazette, May 26, 2011, https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2011/05/a-degree-delivered/.

-

Maycock and Sullivan, Building Old Cambridge, 755.

-

Du Bois, Black Reconstruction, 7.

-

United States Bureau of the Census, A Century of Population Growth from the First Census of the United States to the Twelfth, 1790–1900 (Baltimore, MD: Genealogical Publishing Company, 1969), 5, https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1900/century-of-growth/1790-1900-century-of-growth-part-1.pdf.

-

White indentured servants in the New England colonies faced harsher conditions than those in England, but in general could count on masters to honor the agreed upon duration of their indenture and release them at the end of their terms. For Native people, however, masters routinely ignored terms of indenture and held servants for life—sometimes forcing their children into servitude as well—effectively rendering them enslaved in practice regardless of whether the law allowed it or not. See Newell, 12–15, “‘As good if not better then the Moorish Slaves’: Law, Slavery, and the Second Native Diaspora,” chap. 7, and “To be sold ‘in any part of ye kings Dominyons’: Judicial Enslavement of New England Indians,” chap. 9 in Brethren by Nature.

-

Edward Randolph: Including His Letters and Official Papers from the New England, Middle, and Southern Colonies in America, with Other Documents Relating Chiefly to the Vacating of the Royal Charter of the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, 1676–1703, with historical illustrations and a memoir by Robert Noxon Toppan, 5 vols. (Boston, MA: The Prince Society, 1898), 2:236, https://books.google.com/books?id=iaAUAAAAYAAJ, quoted in Paz, “On the Edge of Freedom,” 38, accessed March 1, 2024, https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis/905/.

-

Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society, 3rd ser., vol. 8 (Boston, MA: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1843), 337, https://archive.org/details/s3collections07massuoft/page/304/mode/2up?view=theater, quoted in Moore, History of Slavery, 49, https://books.google.com/books?id=ohsEAAAAYAAJ. Brackets in original.

-

The monopoly’s revocation allowed the colonists to legally enter the African slave trade. Prior to this change they had relied on New England traders who enslaved people off the eastern coast of Africa and smuggled them into the colonies—a much longer though altogether less perilous journey. Paz, “On the Edge of Freedom,” 38 n. 28, accessed March 1, 2024, https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis/905/, citing “An Act to Settle the Trade to Africa,” July 5, 1698, in Documents Illustrative of the History of the Slave Trade to America, 4 vols., ed. Elizabeth Donnan (Washington, DC: Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1930), 1:421–429.

-

W. E. B. Du Bois, The Suppression of the African Slave Trade to the United States of America, 1638–1870 (New York, NY: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1896), 31, https://books.google.com/books?id=fUgXAAAAYAAJ.

-

Warren, “The Selling of Adam,” chap. 7 in New England Bound.

-

The import duties were part of a clause attached to a law prohibiting interracial sexual relations. See “An Act for the Better Preventing of a Spurious and Mixt Issue, 1705” in ed. Donnan, Slave Trade to America, 3:20.

-

“An Act to Encourage the Importation of White Servants, 1709,” in The Acts and Resolves, Public and Private, of the Province of the Massachusetts Bay: to Which Are Prefixed the Charters of the Province. With Historical and Explanatory Notes, and an Appendix. Published under Chapter 87 of the Resolves of the General Court of the Commonwealth for the Year 1867, vol. 1 (Boston, MA: Wright & Potter, printers to the state, 1869), 634, https://books.google.com/books?id=fQZHAQAAIAAJ.

-

Paz, “On the Edge of Freedom,” 38–39 and n. 29, accessed March 1, 2024, https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis/905/. For 1708 figures, see Moore, History of Slavery, 49. For 1720 figures, see “An Answer to the First Query Propos’d by the Right Honorable the Lords of Trade &c Referring to the Province of the Massachusetts Bay,” in James Phinney Baxter, ed., History of the State of Maine Containing the Baxter Manuscripts, 24 vols. (Portland, ME: Lefavor-Tower Company, 1907), 10:106–107, https://archive.org/details/baxtermanuscript02lcbaxt/page/n7/mode/2up.

“Though enslaved people never made up more than 5 or 10 percent of the population in New England’s largest towns, and far less than that in rural areas, they nonetheless played a significant role in keeping the region’s premodern economy functioning and growing,” Warren, New England Bound, 133.

-

Lawrence William Towner, A Good Master Well Served: Masters and Servants in Colonial Massachusetts, 1620–1750 (New York, NY: Garland Publishing, 1998), 88.