Charles B. Davenport, William E. Castle, and the International Eugenics Movement

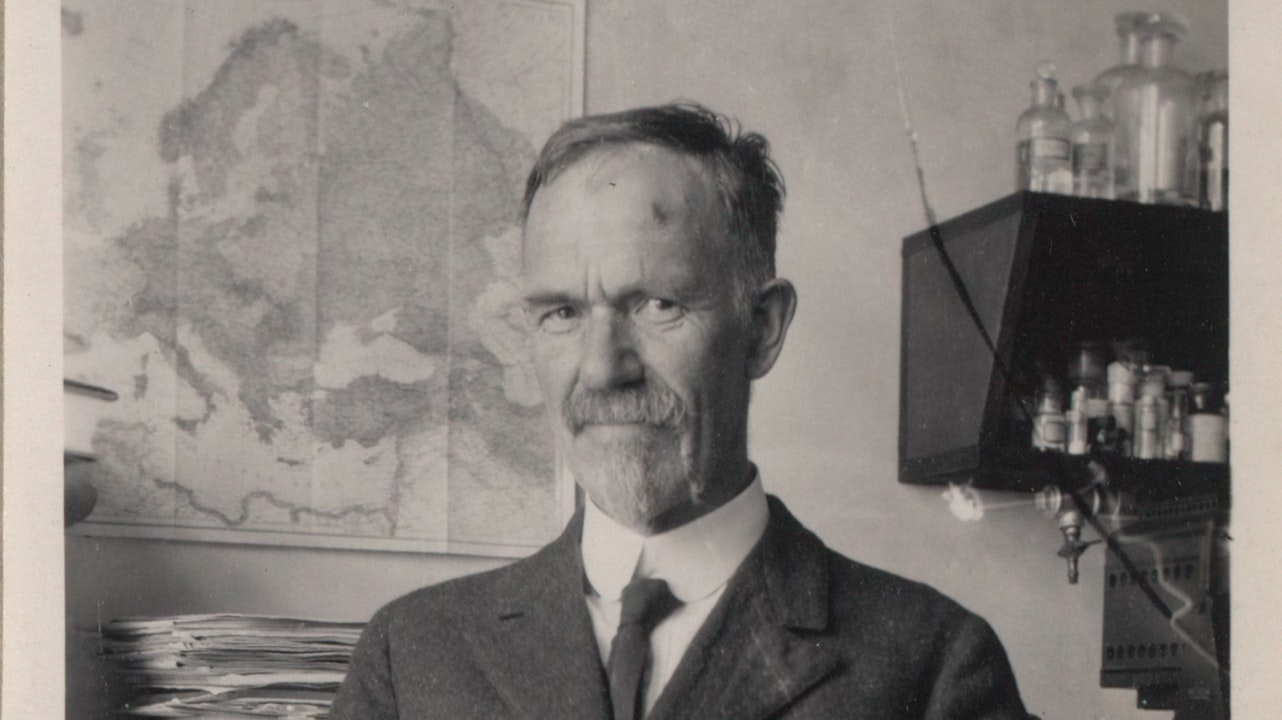

As the eugenics movement took hold in the early 20th century, another Harvard affiliate, Charles B. Davenport (AB 1889; AM 1890; PhD 1892), became one of its key leaders.Go to footnote 504 detail Davenport studied biology at Harvard and stayed on as an instructor until 1899, when he joined the faculty of the University of Chicago. In 1910, Davenport and his fellow eugenics leader Harry H. Laughlin established the Eugenics Record Office in Cold Spring Harbor, New York,Go to footnote 505 detail which became a center for the eugenics movement and produced a wide range of research and propaganda.Go to footnote 506 detail His 1911 book, Heredity in Relation to Eugenics, became the standard text for eugenics courses at colleges and universities across the country and was cited by more than a third of high-school biology textbooks of the era.Go to footnote 507 detail Like his fellow eugenicists, Davenport believed in biological differences among races and the distinctiveness and superiority of the white race, and he virulently opposed race mixing. He advocated for racial restrictions on immigration; “selective elimination” of undesirable people; and acceptance of “the principle of the inequality of generating strains” and “eugenical ideals … in mating,” such that “strains with new and better combinations of traits may arise and our nation take front rank in culture among the nations of ancient and modern times.”Go to footnote 508 detail

Davenport had a significant impact on his students during his decade as an instructor at the University. Among them was a young William Ernest Castle, who would himself go on to become a major figure in eugenics at Harvard and in the United States.Go to footnote 509 detail Castle enrolled at Harvard College in 1892, pursuing a second bachelor’s degree—he had previously graduated from Denison University—in botany and zoology. Castle worked as a laboratory assistant for Davenport and completed a PhD under the direction of E. L. Mark, the professor of zoology who had also advised Davenport.Go to footnote 510 detail After teaching for two years at the University of Wisconsin and Knox College, Castle returned to Harvard in 1897 as an instructor and researcher in animal breeding, first at the Museum of Comparative Zoology, later at the Bussey Institution, and then the University’s center for agriculture and horticulture.Go to footnote 511 detail

Castle was a prominent member of the American Breeders’ Association (today the American Genetic Association) and a founding member of the editorial board of the journal Genetics.Go to footnote 512 detail In 1912, he was chosen as a member of the American Consultative Committee at the First International Eugenics Congress in London, where Charles William Eliot was then serving as vice president.Go to footnote 513 detail

From 1910 to 1930, Castle taught Genetics and Eugenics, one of several courses on eugenics offered across Harvard at the time.Go to footnote 514 detail He published his lecture notes in 1916 in the textbook Genetics and Eugenics: A Text-book for Students of Biology and a Reference Book for Animal and Plant Breeders,Go to footnote 515 detail which deployed his research into the breeding of animals to advance eugenicist arguments about humans in a concluding chapter titled “The Possibility and Prospects of Breeding a Better Human Race.”Go to footnote 516 detail On race mixing, Castle argued that “from the viewpoint of a superior race there is nothing to be gained by crossing with an inferior race. … From the viewpoint of the inferior race also the cross is undesirable if the two races live side by side, because each race will despise individuals of mixed race and this will lead to endless friction.”Go to footnote 517 detail Moreover, to prevent the inheritance of undesirable traits, Castle concluded that “segregation” of the “feeble-minded” should be implemented in “schools and institutions under state control.” When “segregation is impracticable,” Castle argued, the “feeble-minded … should not be allowed to marry unless first sterilized.”Go to footnote 518 detail

Such ideas, which led to compulsory sterilization practices in approximately 30 states and between 60,000 and 70,000 cases of eugenic sterilization in the United States,Go to footnote 519 detail were also a primary focus of Davenport’s Eugenics Record Office (ERO).Go to footnote 520 detail The ERO quickly gained national and international prominence, and it sustained a dual mission to carry out research and advocate for eugenic research and eugenic policy among the public.Go to footnote 521 detail The organization received funding from the Gladys and Roland Harriman Foundation, the Rockefeller Foundation, and the Carnegie Corporation of New York—a total of $1.2 million between 1910 and 1940Go to footnote 522 detail—and established European connections, particularly with like-minded proponents of eugenics in interwar Germany.

Indeed, the ERO’s Eugenical News introduced German eugenics to an American audience, praised a Nazi sterilization law that drew on ERO research, and became “the main propagandists for the German eugenical cause.”Go to footnote 523 detail As president of the International Federation of Eugenic Organizations, Davenport himself helped restore German eugenicists to a place of prominence in the international movement after World War I.Go to footnote 524 detail At his alma mater, Davenport arranged for a delegation of German eugenicists to participate in Harvard’s 1936 tercentenary celebration.Go to footnote 525 detail