Black Students at Harvard: A Legacy of Resistance

Just as legacies of slavery continued to shape campus life long after the Civil War and well into the 20th century, so too did Black resistance. Throughout the postbellum era and into the 20th century, Black students confronted and resisted marginalization, earning their Harvard educations and, ultimately, reshaping the nation.

W. E. B. Du Bois

W. E. B. Du Bois once recalled: “I was in Harvard, but not of it, and realized all the irony of my singing ‘Fair Harvard.’”Go to footnote 608 detail Reflecting decades later on his experience as a Black student at Harvard, Du Bois declared that the University had “a galaxy of great men and fine teachers,” Albert Bushnell Hart among them. Yet, he wrote, “I went to Harvard as a Negro … recognizing myself as a member of a segregated caste whose situation I accepted.”Go to footnote 609 detail Of his social relationships, he wrote: “Following the attitudes which I had adopted in the South, I sought no friendships among my white fellow students, nor even acquaintanceships. Of course I wanted friends, but I could not seek them.”Go to footnote 610 detail A lover of music and singing, he was rejected from the Glee Club: “I ought to have known that Harvard could not afford to have a Negro on its Glee Club traveling about the country.”Go to footnote 611 detail

Even moments of triumph were tinged: When Du Bois and his fellow Black student Clement G. Morgan were selected as Commencement speakers, Francis Greenwood Peabody—Plummer Professor of Christian Morals at Harvard Divinity School and preacher to the University—moved to consult the Harvard Corporation as to whether it was appropriate to select two Black students for this honor.Go to footnote 612 detail Their answer was no; Du Bois spoke, but Morgan did not.Go to footnote 613 detail In the end, Du Bois was lauded for his address “Jefferson Davis: Representative of Civilization.”Go to footnote 614 detail Yet even a Harvard professor who recounted a “trustee’s” view that the paper was “masterly in every way” felt compelled to add that “Du Bois is from Great Barrington, Massachusetts, and doubtless has some white blood in his veins.”Go to footnote 615 detail

Du Bois arrived at Harvard having already completed his undergraduate studies at the historically Black Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee. Harvard, unwilling to accept his Fisk credential, required Du Bois to complete a second bachelor’s degree.Go to footnote 616 detail Fisk, like other Black institutions, was not accredited; the Southern Association of Colleges did not grant accreditation to Fisk or any other Black college in this era.Go to footnote 617 detail Du Bois enrolled in the College as a junior and graduated cum laude in history in 1890.Go to footnote 618 detail He completed a master’s degree in 1891 and earned his PhD in 1895.

During his time at Harvard, Du Bois’s financial struggles set him even further apart from many of his white classmates. As an undergraduate, he had to rely on outside funding and charitable loans to cover tuition and living expenses.Go to footnote 619 detail Unable to afford student housing, he did not live on campus; and his landlady, Mary Taylor, a Black woman from Nova Scotia, let him “owe the rent.”Go to footnote 620 detail As a graduate student, Du Bois was better financially equipped: he had inherited money from his grandfather, and, with the help of recommendations from Hart and another Harvard professor, James Bradley Thayer, Du Bois was awarded the Henry Bromfield Rogers Memorial Fellowship from 1890 to 1892.Go to footnote 621 detail

Du Bois’s experience as a Harvard alumnus mirrored, in some ways, the marginalization he faced on campus. In his autobiography, he wrote of his discomfort at visiting the Harvard Club of New York around 1950 as the guest of a white classmate and club member.Go to footnote 622 detail Some eight years earlier, in 1942, Du Bois had received what appears to be a form letter recruiting new members, prompted by the club’s loss of income with so many members leaving for the warfront.Go to footnote 623 detail Du Bois responded:

My dear Sir: Your letter … rather astonished me. I have been graduated from Harvard College over fifty years and this is the first time during that period that I have been asked to join a Harvard Club. I have assumed that the reason for this reticence was that I am of Negro descent. Possibly, however, Harvard is learning something from this war for democracy and has changed her attitudes. If this is true, I shall be very glad to hear from you and to become a member.Go to footnote 624 detail

There are no records of a reply from the club or a membership in Du Bois’s name.Go to footnote 625 detail

As much as Du Bois’s experience with the Harvard community—as both student and alumnus—illustrates the racism and disenfranchisement of that era on campus, it is also a powerful story of resistance. He directly and publicly challenged ideas and ideologies advanced by Harvard professors and administrators, including Dean Nathaniel Southgate Shaler and President Charles William Eliot.Go to footnote 626 detail His dissertation, titled “The Suppression of the African Slave Trade to the United States of America, 1638–1870,” pushed against the common understanding of slavery at the time, casting it as a moral failure with lasting consequences.Go to footnote 627 detail

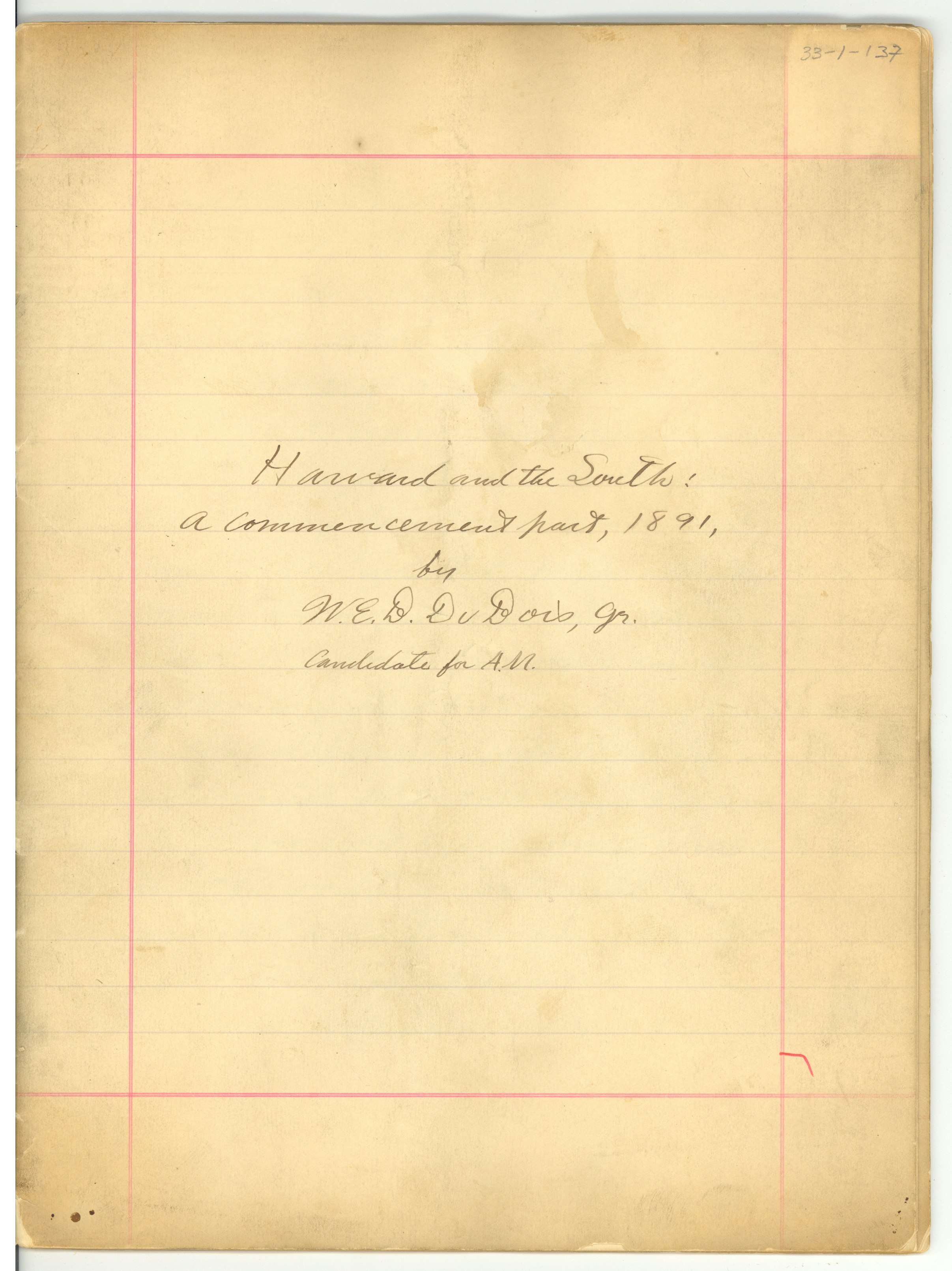

Another piece from Du Bois’s graduate student years, “Harvard and the South,” not only illustrates his willingness to enter the fraught discourse on the post–Civil War South but also offers glimpses into his experience, having been privy to intellectual discussions in which he was uniquely implicated because of his race. The paper argues that the Civil War was “at core the result of a vast economic mistake” and that the solution to the South’s problems of the day “lies in the trained leadership toward correct economic ideas” and “the intellectual impetus of the broadly trained university man.”Go to footnote 628 detail In one particularly telling passage, Du Bois notes his distance from the “Northern student of Southern affairs,” who, he writes, “wavers between calling the whites rascals, or the Negroes idiots.” The Northern student, he writes, “cannot decide whether to make out my Southern fellow student as a case of total depravity; or me as a specimen of the anthropoid ape.” Then, directly challenging his classmates’ stereotypes, he adds: “With as little personal bias as could be expected under the circumstances, I respectfully submit that he need do neither.”Go to footnote 629 detail Du Bois subtly acknowledges the prejudice—whether scientific, social, or religious in nature—of his Harvard audience:

If the Southern people can once be brought to see that it is to their highest economic advantage to have their working classes as intelligent and ambitious and with as great political privileges as possible, I care not what they or you think as to the origen and destiny of the Negro people.Go to footnote 630 detail

Long after earning his PhD, Du Bois remained active within the Harvard community, including attending reunions, and he continued to push Hart, with whom he stayed in regular contact, on matters of representation. For example, Du Bois responded to a letter from Hart wishing him well on his 50th birthday with the following note:

My dear Prof. Hart: I want to thank you very much for the kind letter which you sent on my birthday. I have been noticing that “The American Year Book” with which you are connected, always says surprisingly little about the Negro of America and elsewhere. Cannot something be done about this?Go to footnote 631 detail

Du Bois also worked to hold the University accountable.Go to footnote 632 detail In 1922 and 1923, leading up to the petition against President Abbott Lawrence Lowell’s exclusion of Black students from freshman dormitories, Du Bois consulted with the organizing alumni, sharing suggestions and contacts.Go to footnote 633 detail He was “shocked” and enraged by the exclusion of the high-achieving Blacks admitted to Harvard. And he brought national attention to the issue by unleashing what biographer David Levering Lewis called a “double-barreled” critique of anti-Black discrimination and the use of anti-Jewish quotas by “Fair (!) Harvard” in the August 1922 issue of Crisis, the magazine of the NAACP.Go to footnote 634 detail The dormitory exclusion distressed Du Bois, Lewis argued, because it showed that “mainstream America recognized no amount of merit, conceded not even the most minimal authority … however rarely talented, insofar as Negro citizens were concerned.”Go to footnote 635 detail

Du Bois’s role in cofounding the NAACP—the nation’s oldest civil rights organization—was his most profound act of resistance to the marginalization of African Americans in American society. Under the aegis of that organization and its lawyers, Black Americans struggled against discrimination in the political process, housing, public accommodations, the criminal legal system, and education.Go to footnote 636 detail The organization’s legal strategy against segregation prevailed in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), one of the most celebrated cases in the canon of American constitutional law.Go to footnote 637 detail Thurgood Marshall and a team that included the Harvard-educated Black lawyers Charles Hamilton Houston (LLB 1922, SJD 1923), William H. Hastie (LLB 1930; SJD 1933), and William T. Coleman Jr. (LLB 1946) played leading roles in the lawsuit that “reconsecrated American ideals.”Go to footnote 638 detail

Ewart G. Guinier

Ewart G. Guinier, who would go on to serve as chair of Harvard’s Department of Afro-American Studies at its founding in 1969,Go to footnote 639 detail was a student well after Du Bois had left campus. He enrolled at Harvard in 1929, during Abbott Lawrence Lowell’s presidency, and was subject to the admissions practices Lowell had put in place. After graduating with honors from Boston’s English High School, Guinier applied and was accepted to both Dartmouth College and Harvard.Go to footnote 640 detail While Dartmouth offered a full scholarship including room and board, Harvard offered nothing. But Guinier was determined to attend the University. He turned down the full scholarship at Dartmouth and worked summers and throughout the school year to pay his way at Harvard.Go to footnote 641 detail

Despite Harvard’s new, ostensibly nondiscriminatory housing policy, Guinier was notified that he “had been granted permission to live at home”—permission he had not requested. As a freshman, Guinier would commute to campus from Roxbury, and during his sophomore year, he stayed in Brookline.Go to footnote 642 detail Both locations are several miles from campus.

Guinier’s first week at Harvard was jarring.Go to footnote 643 detail When he attended the freshman assembly to hear Lowell speak, he recalled:

There seemed to be a thousand people in the hall. I was the only Black. As we left the meeting I could hear conversations being started all around me,—but no one looked me in the eye, no one spoke to me. As I walked toward a group, they would move away.Go to footnote 644 detail

Later, Guinier was excited to encounter a familiar face—a former schoolmate—working the desk of the freshman library, but again, he was ignored. It was not until shopping for textbooks at the Harvard Coop that Guinier met another Black student, Ralph Bunche (MA 1928; PhD 1934), who welcomed him to Harvard. Bunche, who became an acclaimed diplomat, would go on to receive the Nobel Peace Prize in 1950 and play an important role in the Civil Rights Movement.Go to footnote 645 detail “He was the first person who spoke to me voluntarily,” said Guinier, “and gave me some sense of community and connection with Harvard.”Go to footnote 646 detail Bunche also told Guinier to look for a job at one of the private student eating clubs that catered to wealthy white students, where he could work alongside other Black students.Go to footnote 647 detail

Classes were not much better, and Guinier’s professors rarely called on him.Go to footnote 648 detail He was “invisible to everyone around me,” treated as a “non-person,” he recalled.Go to footnote 649 detail Things improved when he joined Alpha Phi Alpha and Omega Psi Phi, two Black fraternities with local chapters, but he suffered from health problems, and his family faced financial difficulties.Go to footnote 650 detail Guinier was forced to transfer to City College in New York in 1931.Go to footnote 651 detail

Undeterred by these challenges, Guinier completed his undergraduate studies and went on to earn a master’s degree from Columbia University and a law degree from New York University. He became a prominent trade unionist, served as international secretary for the United Public Workers of America, and was the first Black candidate to be nominated by a political party—the American Labor Party—for the Manhattan borough presidency.Go to footnote 652 detail

In a turn of events that illustrates both Black intellectual resistance to inequality and institutional change over time, the history of the Guinier family and of Harvard remain deeply entwined. Both Guinier’s daughter, Lani Guinier (Radcliffe AB 1971), and his grandson, Nikolas Bowie (AM 2011, JD 2014, PhD 2018), followed him to Harvard first as students and later as members of the faculty.Go to footnote 753 detail In 1998, Lani Guinier made history as the first Black woman to hold a tenured professorship at Harvard Law School.Go to footnote 653 detail

Footnotes

-

Du Bois, “A Negro Student at Harvard,” 443.

-

Text quoted in this and the prior sentence is from Du Bois, “A Negro Student at Harvard,” 439.

-

Du Bois, “A Negro Student at Harvard,” 441. This sentiment is challenged to at least some degree by an account of Robert Morse Lovett, whom he called “perhaps the closest white student friend I made at Harvard.” See W. E. B. Du Bois The Autobiography of W. E. B. Du Bois: A Soliloquy on Viewing My Life from the Last Decade of Its First Century (New York, NY: International Publishers, 1968), 278.

-

Du Bois, “A Negro Student at Harvard,” 441.

-

Bruce A. Kimball, “‘This Pitiable Rejection of a Great Opportunity’: W. E. B. Du Bois, Clement G. Morgan, and the Harvard University Graduation of 1890,” The Journal of African American History 94, no. 1 (Winter 2009): 12. Kimball notes that Du Bois was at the time enrolled in Peabody’s course, “Ethics of Social Reform.” On Peabody, see “Francis Greenwood Peabody,” Harvard Divinity School Library, accessed February 1, 2022, https://library.hds.harvard.edu/exhibits/hds-20th-century/peabody.

-

Kimball, “‘Pitiable Rejection’, 12–14. Morgan was allowed to speak at Class Day, the day before Commencement.

-

Du Bois, Autobiography, 418.

-

Du Bois, “A Negro Student at Harvard,” 453. While this professor may be speaking by conjecture, Du Bois’s racial makeup was known to Harvard through Dudley Allen Sargent’s intake forms. See [measurement card and photograph of W. E. B. Du Bois], #3129, box 9, Records of the Department of Physical Education: anthropometric measurements of Harvard students, 1860–1920, UAV 689.270.7p, Harvard University Archives.

-

Lewis, Du Bois (1993), 82.

-

On Fisk, see “Fisk University Accreditation,” Fisk University, accessed January 7, 2022, https://www.fisk.edu/about/accreditation/. Saran Donahoo and Wynetta Y. Lee, “The Adversity of Diversity: Regional Associations and the Accreditation of Minority-Serving Institutions,” chap. 19 in Understanding Minority-Serving Institutions, ed. Marybeth Gassman, Benjamin Baez, and Caroline Sotello Viernes Turner (New York, NY: State University of New York Press, 2008), discusses the historical exclusion of HBCUs by accrediting organizations. The Southern Association of Colleges and Schools (SACS)—the regional accreditor for 80% of HBCUs—had “both written and unwritten policies denying membership to HBCUs” until the 1930s, when they began granting limited accreditation to some HBCUs without permitting them full membership. SACS only began granting HBCUs full membership in 1956, see Donahoo and Lee, “The Adversity of Diversity,” 294.

In one instance, an HBCU was denied accreditation based on “the quality and size of its library, the lack of advanced degrees among its faculty, and the low salary scales for members of its faculty who had advanced training, experience and responsibilities”—in other words, because of the lack of funding and high educational achievement that were systematically denied to educational organizations serving Black communities. James D. Anderson, “Philanthropy, the State and the Development of Historically Black Public Colleges: The Case of Mississippi,” Minerva 35, no. 3 (September 1997): 300.

-

Lewis, Du Bois (1993), 81–82.

-

Lewis, Du Bois (1993), 82–84, 96–97, 100.

-

Lewis, Du Bois (1993), 84. This home, at 20 Flagg St., is identified with a historical marker and is part of Cambridge’s African American Heritage Trail, accessed February 2, 2022, https://www.cambridgema.gov/historic/cambridgehistory/historicmarkers#aaht.

-

Lewis, Du Bois (1993), 103; Du Bois, “A Negro Student at Harvard,” 454; Du Bois, W. E. B. , Student Folder, Harvard University Archives.

-

Du Bois, Autobiography, 278.

-

Harvard Club of New York City to W. E. B. Du Bois, November 17, 1942, W. E. B. Du Bois Papers, MS 312, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries, http://credo.library.umass.edu/view/full/mums312-b098-i060.

-

W. E. B. Du Bois to Harvard Club of New York City, December 16, 1942, W. E. B. Du Bois Papers, MS 312, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries, http://credo.library.umass.edu/view/full/mums312-b098-i061.

-

See “Harvard Club of New York membership card, ca. 1900,” W. E. B. Du Bois Papers, MS 312, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries, https://credo.library.umass.edu/view/full/mums312-b158-i029. Despite the title of this archival record, the object does not in fact appear to be a permanent membership card.

-

Shaler, Dean of the Lawrence Scientific School from 1891 to 1906, wrote, “The African and European races must remain distinct in blood … it is their duty to remain apart.” See Livingstone, “Science and Society,” 193.

-

Lewis, Du Bois (1993), 154–155.

-

W. E. B. Du Bois. “Harvard and the South: A Commencement Part, 1891,” W. E. B. Du Bois Papers, MS 312, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries, 1, 10–11, http://credo.library.umass.edu/view/full/mums312-b230-i012.

-

Text quoted in this and the two prior sentences is from Du Bois, “Harvard and the South,” 10.

-

Du Bois, “Harvard and the South,” 15.

-

W. E. B. Du Bois to Albert Bushnell Hart, April 15, 1918, W. E. B. Du Bois Papers, MS 312, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries, http://credo.library.umass.edu/view/full/mums312-b011-i339.

-

Kimball, “Pitiable Rejection,” 16; Perkins, “African American Female Elite,” 720. See also Lewis, Du Bois (2000), 90–91, 99–100.

-

Lewis S. Gannett to W. E. B. Du Bois, March 3, 1922, W. E. B. Du Bois Papers, MS 312, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries, http://credo.library.umass.edu/view/full/mums312-b019-i274; W. E. B. Du Bois to Lewis S. Gannett, March 13, 1922, W. E. B. Du Bois Papers, MS 312, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries, http://credo.library.umass.edu/view/full/mums312-b019-i279; W. R. Valentine to W. E. B. Du Bois, May 11, 1922, W. E. B. Du Bois Papers, MS 312, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries, http://credo.library.umass.edu/view/full/mums312-b020-i205.

-

Text quoted in this and the prior sentence is from Lewis, Du Bois (2000), 90. Lewis is discussing Du Bois’s essays “Opinion of W. E. B. Du Bois” and “FAIR (!) HARVARD,” both published in The Crisis 24, no. 4 (August 1922), https://modjourn.org/issue/bdr521604/#.

-

Lewis, Du Bois (2000), 100.

-

See Mark V. Tushnet, The NAACP’s Legal Strategy against Segregated Education, 1925-1950 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1987); McNeil, Groundwork.

-

McNeil, Groundwork, 200–201.

-

McNeil, Groundwork, 53. See also “This Fight … Is Not an Isolated Struggle,” chap. 10 in ibid.. Notably, Dean Roscoe Pound and Professor Felix Frankfurter encouraged and mentored Houston.

-

“Department of African and African American Studies Timeline,” Harvard University, accessed February 4, 2022, https://hwpi.harvard.edu/files/aaas/files/department_of_african_and_african_american_studies_timeline.pdf.

-

Eugenia Guinier to Howard Dodson, n.d., box 1, folder 2, Eugenia Guinier—“Recollections and Insights into Ewart G. Guinier,” Ewart Guinier papers, 1910–1989, Sc MG 420, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library. This and many of the following details about Ewart Guinier’s experiences as a student at Harvard were also recounted in his daughter Lani Guinier’s essay “My Father’s Undergraduate Years at Harvard College,” The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education 21 (Autumn 1998): 104–105.

-

Ewart Guinier and Susan Gordon, “Trapped at Harvard,” unpublished manuscript, p. 1–2, 6, 10–11, box 1, folder 9, Autobiographical, Ewart Guinier papers, 1910–1989, Sc MG 420, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library.

-

Text quoted in this and the prior sentence is from Guinier and Gordon, “Trapped at Harvard,” p. 2–3, 10–11, New York Public Library.

-

Eugenia Guinier to Howard Dodson, n.d., Ewart Guinier papers, New York Public Library.

-

Guinier and Gordon, “Trapped at Harvard,” p. 4, New York Public Library. See also L. Guinier, “Father’s Undergraduate Years,” 104.

-

“The Nobel Peace Prize 1950: Ralph Bunche—Biographical,” The Nobel Prize, accessed January 11, 2022, https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/1950/bunche/biographical/.

-

Guinier and Gordon, “Trapped at Harvard,” p. 5–6, New York Public Library.

-

Guinier and Gordon, “Trapped at Harvard,” p. 6, New York Public Library.

-

Guinier and Gordon, “Trapped at Harvard,” p. 8, New York Public Library.

-

Guinier and Gordon, “Trapped at Harvard,” p. 9, New York Public Library.

-

Guinier and Gordon, “Trapped at Harvard,” p. 11, New York Public Library.

-

Eugenia Guinier to Howard Dodson, n.d., Ewart Guinier papers, New York Public Library. See also “Biographical/Historical Information,” Ewart Guinier Papers, 1910–1989, New York Public Library Archives and Manuscripts, accessed February 4, 2022, https://archives.nypl.org/scm/20650.

-

Information in this and the prior sentence is from “Biographical/Historical Information,” Ewart Guinier Papers, 1910-1989, New York Public Library.

-

See Brett Milano and HLS Correspondent, “In Memoriam: Lani Guinier 1950–2022,” Harvard Law Bulletin, January 7, 2022, https://hls.harvard.edu/today/in-memoriam-lani-guinier-1950-2022/; “Nikolas Bowie,” Harvard Law School, accessed April 23, 2024, https://hls.harvard.edu/faculty/nikolas-bowie/.

-

See Ethan Bronner, “Lani Guinier Joins Faculty Of Law School At Harvard,” New York Times, January 24, 1998, https://nyti.ms/3oI1eCg. For many years before Guinier’s appointment, Derrick Bell, the first Black professor appointed to the Harvard Law School faculty, and students staged protests seeking greater faculty diversity. See, for example, Fox Butterfield, “Harvard Law Professor Quits Until Black Woman is Named,” New York Times, April 24, 1990, https://nyti.ms/3oD2x5t.