Abbott Lawrence Lowell and Discrimination in Admissions and Housing

Two major avenues for discrimination in the University setting, admissions and housing, figured prominently in the long Harvard presidency (1909–1933) of Abbott Lawrence Lowell. Lowell, who succeeded Charles William Eliot, guided Harvard through a period of significant growth—enrollment nearly doubled, and the endowment quintupled. His administration also gave rise to several highly publicized controversies related to discrimination on the basis of religion and race.Go to footnote 534 detail

Early in Lowell’s presidency, the Faculty of Arts and Sciences voted to supplement the University’s existing exam-based admissions system with an alternative “approved secondary school course” route.Go to footnote 535 detail In keeping with Harvard’s long-standing vision of itself as a national institution, the express purpose of this change was to increase enrollments from outside New England as well as from public high schools, where students were less likely to receive preparation for college entrance exams.Go to footnote 536 detail The decision attracted notice well beyond the Harvard community: in a letter to Lowell, the businessman and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie lauded the University for creating a “clear path for the poor boy from bottom to top.”Go to footnote 537 detail In practice, however, Lowell would work to limit the new process’s effect upon the socioeconomic makeup of the student body,Go to footnote 538 detail and to instead promote discriminatory admissions practices.

As part of Harvard’s evolving admissions policies, Lowell masterminded Harvard’s well-documented efforts to exclude Jewish students in the early 20th century. He did this in a variety of ways: first by privately tilting the admissions scale against Jewish transfer applicantsGo to footnote 539 detail and adopting a national recruitment strategy focused on regions of the country with smaller Jewish populations,Go to footnote 540 detail and then by capping the number of Jewish students admitted and introducing new admissions criteria.Go to footnote 541 detail These criteria, including personal interviews and the requirement that all candidates submit photographs with their application materials, were approved by the faculty in January 1926.Go to footnote 542 detail And, at Lowell’s behest, the Committee on Admission was granted discretion to execute, in his words, a “discrimination among individuals.”Go to footnote 543 detail

Inside and outside of the Ivy League, universities deployed many of these same policies and practices, including photo requirements, interviews, admissions tests, and recruitment from private preparatory and other urban feeder schools in ways that discriminated against or disadvantaged Black students.Go to footnote 544 detail

But plain indifference or outright exclusion from white institutions of higher education were the more pressing problems for African Americans, as evinced by the small number of Blacks admitted to Harvard before, during, and well after the 64-year tenure of Presidents Eliot and Lowell.Go to footnote 545 detail Despite access to civic organizations in major cities that could identify a pool of able Black students, the college enrolled meager numbers.Go to footnote 546 detail “The official view was that African Americans who had the grades and money to come to Harvard were welcome,” wrote two historians of the institution, but no effort was made to find, recruit, or welcome those students to campus.Go to footnote 547 detail Approximately 160 Black men matriculated to Harvard College during the 50-year period from 1890 to 1940, an average of 3 per year, 30 per decade.Go to footnote 548 detail Such vanishingly small numbers frequently left Black men isolated and marginalized on campus.Go to footnote 549 detail

Those Blacks who did manage to enter Harvard’s gates during the 19th and early-to-mid 20th centuries excelled academically, earning equal or better academic records than most white students, but encountered slavery’s legacies on campus.Go to footnote 550 detail

Lowell’s perspective on questions of race—rooted in racial hierarchy and eugenics—shaped campus life. He granted Charles B. Davenport and the Eugenics Record Office (ERO) access to “the physical and intellectual records” of Harvard students for eugenics research.Go to footnote 551 detail And in response to a request from a Harvard faculty member, Lowell lobbied a US senator to support immigration quotas,Go to footnote 552 detail in keeping with his views “that no democracy could be successful unless it was tolerably homogeneous; and that the presence of [different] races which did not intermingle was unfortunate, as indeed it has been in the case of the negro.”Go to footnote 553 detail

Lowell’s views resulted in a notorious example of Black marginalization on campus. In the summer of 1922, when Harvard was already under fire in the press over “the Jewish question”—the University’s anti-Jewish admissions policies—a new controversy developed: President Lowell’s signature innovation—a residential college experience for first years that was meant to build community—excluded the handful of Black Harvard students. The community Lowell sought to build included whites only.Go to footnote 554 detail

The seeds of this so-called “dormitory crisis” had been planted the previous spring when William J. Knox Jr., a newly admitted Black freshman from New Bedford, Massachusetts—and a great-nephew of the Black abolitionist Harriet JacobsGo to footnote 555 detail—was barred from living in the freshman dormitories.Go to footnote 556 detail Knox had initially been granted a room but, shortly after appearing in person for an entrance examination, he received a telegram asking that he return his registration card. One week later, Knox received a letter informing him that the freshman halls were full.Go to footnote 557 detail

Knox traveled to Cambridge with the fellow New Bedford native and recent Harvard College graduate Edwin B. Jourdain Jr. (AB 1921), then enrolled in Harvard Business School, to inquire after the change.Go to footnote 558 detail Jourdain had, after all, been permitted as a Black student to live in the freshman halls just a few years earlier. Dean Philip P. Chase informed Knox and Jourdain of Harvard’s policy: while Black students were allowed in voluntary residence and dining halls, they were excluded from the freshman halls because residence in those dormitories was compulsory (for whites).Go to footnote 559 detail In Lowell’s view, “Those students whose social prejudice against the negro is strong can hardly be compelled into an association that, rightly or wrongly, is repugnant to them.”Go to footnote 560 detail Jourdain’s admission into the halls was dismissed as a wartime inadvertence,Go to footnote 561 detail and Knox was offered a spot elsewhere.Go to footnote 562 detail

Jourdain pursued the matter further, seeking a conference with President Lowell.Go to footnote 563 detail According to Lowell, he told Jourdain “that negroes were well treated at Harvard and that it would be a mistake for them to urge admission to the Freshman Halls.” Lowell also cautioned that, if “faced by the alternative of either admitting negroes to those halls … or of excluding negroes altogether, we might, or should, be compelled to adopt the latter, like some other colleges.” News of this exchange spread, and Lowell’s words were interpreted as a warning to those who might protest the policy, though he denied this was his intent. Lowell affirmed Harvard’s duty to provide “the best possible opportunities for education,” but doubled down on his position that Harvard did not owe Black students “inclusion in a compulsory social system with other people when it is not mutually agreeable.”Go to footnote 564 detail Still focused on a national student body, it was, Lowell believed, “irrational to contend that on account of the two or three negroes in the freshman class, the College ought practically to drive away the large number of men from the South and West.”Go to footnote 565 detail

The issue gained public attention in the summer of 1922, when word leaked to the New York World that a committee of seven white Harvard alumni, including one Jewish graduate, was circulating a petition among fellow alumni to send to Lowell.Go to footnote 566 detail The petition, which gained more than 140 signatures,Go to footnote 567 detail “respectfully submit[ted]” that exclusion of Black students was a “Jim Crow policy” and argued that, while “the University owes the Southern man the best possible opportunity for education,” it does “not owe him the surrender of our Northern ideas of democracy and our Harvard ideals of justice.” If reversing the exclusionary policy meant a loss of Southerners “of intense race-consciousness,” the petitioners wrote, “the College should accept that loss rather than surrender its standards.”Go to footnote 568 detail

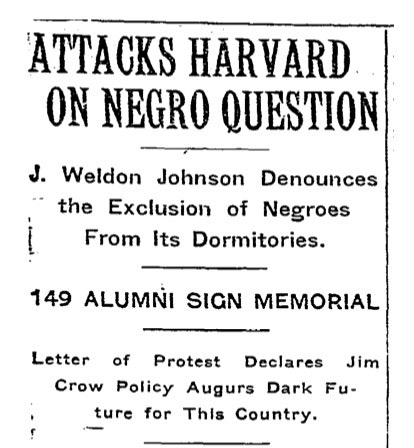

The administration showed no signs of budging until January, after added pressure from prominent Black alumni pushed the controversy onto the national stage and sparked another deluge of letters.Go to footnote 569 detail Roscoe Conkling Bruce (AB 1902), testing the policy, wrote to the registrar in December requesting a place in the freshman halls for his son.Go to footnote 570 detail Lowell’s reply and the ensuing correspondence with Bruce were published in the New York Times. The paper also printed a statement from William Monroe Trotter, on behalf of the National Equal Rights League, decrying Harvard’s “turn from democracy and freedom to race oppression, prejudice and hypocrisy.”Go to footnote 571 detail Another published letter, from James Weldon Johnson on behalf of the NAACP, charged that “by capitulating to anti-negro prejudice in the freshman dormitories or anywhere else, Harvard University affirms that prejudice and strengthens it, and is but putting into effect the program proclaimed by the infamous Ku Klux Klan and its apologists.”Go to footnote 572 detail

By the end of the month, Harvard’s overseers called a special meeting to appoint a faculty committee to consider the issue.Go to footnote 573 detail In March and April, the governing bodies amended Lowell’s policy on freshman housing; henceforth, “men of the white and colored races shall not be compelled to live and eat together, nor shall any man be excluded by reason of his color.” It was not clear what the new policy meant in practice; but it was hardly a ringing endorsement of racial mixing in campus housing.Go to footnote 574 detail

The chilly racial climate on campus extended beyond this notorious incident. In other ways, African Americans encountered impediments to full acceptance.

During the early decades of the 20th century, for instance, the talents of Black Harvard athletes earned them respect and recognition from University leaders and from other students on campus. But these athletes also encountered discrimination and exclusion, especially in intercollegiate play. Black football and baseball players sometimes faced harassment by other teams’ fans. And universities in both the South and the North sometimes refused to play against Harvard teams that included Black players. Harvard administrators often bowed to these demands.Go to footnote 575 detail A controversy over a 1941 lacrosse match under Lowell’s successor as president, James Bryant Conant, illustrated the problem and brought things to a head: William J. Bingham, Harvard’s athletic director, benched Lucien Victor Alexis Jr. (AB 1942; MBA 1947), an African American lacrosse player, after the United States Naval Academy objected. “We were guests of the Naval Academy,” Bingham said, “I had no choice.”Go to footnote 576 detail After an outcry by Harvard students, the Harvard Corporation “suggested” that the athletic director make the University “principle” of non-discrimination known to other institutions.Go to footnote 577 detail

Even as white Harvard students appreciated the Black athletes who contributed to victories on the field, many were indifferent to the overall plight of African Americans. At a time of rising racist violence against African Americans and an NAACP campaign against lynching, for example, Harvard students made light of the resurgent Ku Klux Klan. The white terrorist organization was responsible for anti-Black harassment and murder and the dispossession of Black-owned property across the country.Go to footnote 578 detail Yet the students’ general indifference was on full display at a Class Day ceremony in 1924: the “hit of the afternoon,” according to one Boston newspaper, “was undoubtedly the class of ’21”—the class to which Edwin B. Jourdain Jr. belongedGo to footnote 579 detail—“who came as a klavern of the Ku Klux Klan, white robes, pointed hoods with eyeholes and all.”Go to footnote 580 detail The incident apparently did not spark public outcry or a response from the administration; the Class of 1921 continued to make light of the Klan in its newsletter years later.Go to footnote 581 detail

This was not the first time Harvard students had made light of the Klan. In 1923, the Harvard Crimson published stories about Klan activities around Halloween, and the Harvard Lampoon printed an entire issue on the Klan.Go to footnote 582 detail Such “jokes” are unlikely to have escaped the notice of the University’s few Black students. In fact, the Crimson also reported on Harvard students’ involvement in the Klan, coverage that prompted another response—a telegram to the president and Board of Overseers—from Johnson on behalf of the NAACP.Go to footnote 583 detail

Still, Black students generally could and did participate in campus clubs and activities. They wrote for undergraduate publications, debated, and won academic honors. Appreciative of the opportunities they gained at Harvard, many African Americans spoke fondly of the University. Others reacted with “ambivalence” to the reality of marginalization despite inclusion at the University.Go to footnote 584 detail The decidedly mixed experiences of Blacks at Harvard illustrated a “half-opened door,” as one author aptly termed the Ivy League experience of African Americans during the early and middle decades of the 20th century.Go to footnote 585 detail

Footnotes

-

See “Collection Overview: The Lowell Presidency,” Records of the President of Harvard University, Abbott Lawrence Lowell, Hollis for Archival Discovery, February 25, 2022, https://id.lib.harvard.edu/ead/hua03003/catalog.

-

“At a Meeting of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, January 17, 1911,” box 1, folder 15, Admission -- New Plan for Records of the President of Harvard University, Abbott Lawrence Lowell, [Series 1909-1914] UAI 5.160, Harvard University Archives. The addition of the approved course route for admission became known as the “New Plan of Admission.” For confirmation that the New Plan was implemented in the 1910-1911 school year, see Harvard University, “Appendix -- Report of the Chairman of the Committee on Admission,” Reports of the President and the Treasurer of Harvard College 1912-1913 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University, 1914), 254-261, https://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.ARCH:30013263?n=256.

-

Lowell viewed the shift away from admission only by exam as a means to “make Harvard as national as possible.” Abbott Lawrence Lowell to Andrew Carnegie, January 19, 1911, and Andrew Carnegie to Abbott Lawrence Lowell, January 20, 1911, box 1, folder 15, Admission -- New Plan for Records of the President of Harvard University, Abbott Lawrence Lowell, [Series 1909-1914], UAI 5.160, Harvard University Archives.

-

Andrew Carnegie to Abbott Lawrence Lowell, January 19, 1911, Harvard University Archives; Abbott Lawrence Lowell to Andrew Carnegie, January 20, 1911, Harvard University Archives.

-

Synnott, The Half-Opened Door, 56-57; Karabel, The Chosen, 52.

-

Synnott, The Half-Opened Door, 58, 61.

-

To identify Jewish students, this 1922 Statistical Report used a three-tiered “J1, J2, J3” system, marking the level of certainty of a given individual’s Jewishness. Records consulted included admission forms, registration cards, bursar office records, and senior class albums, and involved looking at a student’s birthplace, school, home address, and parents’ vocations and names (including the mother’s family name in case the family had changed their name) see Synnott, The Half-Opened Door, 93-95. The statistical report is included in Limitation of Numbers, box 197, folder 387, Admission to Harvard College -- Report of Committee on Methods of Sifting Candidates, Records of the President of Harvard University, Abbott Lawrence Lowell, [Series 1925-1928], UAI 5.160, Harvard University Archives.

-

[Abbott Lawrence] Lowell to Henry James, November 3 and 6, 1925, Limitation of Numbers, box 227197, folder 184387, Admission to Harvard College—Report of Committee on Methods of Sifting Candidates, Records of the President of Harvard University, Abbott Lawrence Lowell, [Series 1925–1928], UAI 5.160, Harvard University Archives, quoted in Synnott, The Half-Opened Door, 108. Henry James, the son of William James and nephew of the novelist Henry James, served as a Harvard overseer and the chairman of the Special Committee on the Size of the Freshman Class, which oversaw this review of the admissions process.

-

Synnott, The Half-Opened Door, 109-110.

-

Synnott, The Half-Opened Door, 107-108.

-

On the use of such tactics, particularly interviews and character assessments, by public universities against African American students, see Tomiko Brown-Nagin, Civil Rights Queen: Constance Baker Motley and the Struggle for Equality (New York, NY: Pantheon, 2022), 91-93, 95-96, 100-04, 115-17, 152-53, 155-56, 157.

-

See Morton Keller and Phyllis Keller, Making Harvard Modern: The Rise of America’s University (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2001), 60–63.

-

Synnott, The Half-Opened Door, 38, 40, 47, 207-208, 220; Sollors et al., eds., Blacks at Harvard, 2-3.

-

Keller and Keller, Making Harvard Modern, 61.

-

Synnott, The Half-Opened Door, 47. The University did not keep records identifying students by race for much of its history. As a result, scholars, left to rely on scattered surveys, limited governmental documents, and class book photographs, have struggled to accurately document the Black presence at Harvard.

-

Synnott, The Half-Opened Door, 207-209.; Keller and Keller, Making Harvard Modern, 60-61.

-

Synnott, The Half-Opened Door, 47; Sollors et al., eds., Blacks at Harvard, xxi-xxiii; Perkins, “African American Female Elite,” 728-729.

-

[Abbott Lawrence] Lowell to Charles B. Davenport, April 12, 1913, box 2, unspecified: folder 34, American Breeders' Association, Records of the President of Harvard University, Abbott Lawrence Lowell, 1909-1933: folder lists, UAI 5.160, Harvard University Archives.

-

[Abbott Lawrence] Lowell to LeBaron B. Colt, March 21, 1922, box 174, unspecified: folder 1077, Immigration, Restriction of Records of the President of Harvard University, Abbott Lawrence Lowell, 1909-1933: folder lists, UAI 5.160, Harvard University Archives.

-

[Abbott Lawrence] Lowell to Sidney L. Gulick, August 28, 1918, box 105, unspecified: folder 399, Immigration, Records of the President of Harvard University, Abbott Lawrence Lowell, 1909-1933: folder lists, UAI 5.160, Harvard University Archives.

-

Painter, “Jim Crow at Harvard: 1923”; Sollors et al., eds., Blacks at Harvard, xxi–xxiii; Synnott, The Half-Opened Door, 49-50.

-

Knox's great-aunt Harriet Jacobs authored the famous memoir Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (Boston, MA: self pub., 1861). In the late 19th century, Jacobs lived in Cambridge and ran boarding houses that served Harvard students and faculty, including Harvard Law School Dean Christopher Langdell. See Jean Fagan Yellin, “Harriet Jacobs’s Family History,” American Literature 66, no. 4 (December 1994): 765–767; Jean Fagan Yellin, Harriet Jacobs: A Life (New York, NY: Basic Civitas Books, 2004), 222.

-

See Sollors et al., Blacks at Harvard, 195–227. Five Black freshmen were admitted to the school in the fall of 1921. While residence in the freshman halls was required except in special circumstances, just three of the five admitted Black freshman applied for dormitory residence and only one was granted it. See Raymond Pace Alexander, “Voices from Harvard’s Own Negroes,” Opportunity 1, no. 3 (March 1923): 29–31.

-

See the letter from petitioning Harvard alumni to the President and Fellows of Harvard College in 1922, “Memorial to the Corporation” box 171, unspecified: folder 981, Freshman Dormitories, Records of the President of Harvard University, Abbott Lawrence Lowell, 1909-1933: folder lists, UAI 5.160, Harvard University Archives.

-

Alexander, “Voices from Harvard’s Own Negroes.” See also Lewis, Du Bois (2000), 88-89.

Edwin Jourdain, Jr.’s son Spencer Jourdain—also a Harvard graduate—has chronicled the experiences of his father and other Black students at Harvard in this era in the family memoir The Dream Dancers: An American Reflection Upon Past, Present and Future. He describes his father’s activism during the Dormitory Crisis in vol. 1, New England Preservers of the Dream, 1620-1924 (Evanston, IL: Shorefront Press, 2016), 214-226.

-

“Memorial to the Corporation” (1922), Harvard University Archives.

-

[Abbott Lawrence] Lowell to Frederick L. Allen, October 22, 1921, box 171, folder 981, Freshman Dormitories, Records of the President of Harvard University, Abbott Lawrence Lowell, [Series 1919-1922] UAI 5.160, Harvard University Archives.

There had been incidents, before and after the freshman halls becoming mandatory in 1914, when students objected to their roommates or hall neighbors based on race. The administration always responded with alternative accommodations. See, for example, Richard E. Stifel to S. B. R. Briggs, July 22, 1910, box 12, folder 366, Dormitories -- General Correspondence Records of the President of Harvard University, Abbott Lawrence Lowell, [Series 1909-1914] UAI 5.160, Harvard University Archives, and N. S. Davis to Abbott Lawrence Lowell, October 6, 1915, box 57, folder 70a, Freshman Halls. Records of the President of Harvard University, Abbott Lawrence Lowell, [Series 1914-1917] UAI 5.160, Harvard University Archives.

-

One other Black student, Euclid P. Ghee, one year behind Jourdain, was also permitted to live in the freshman halls. See “NEGRO GRADUATE PROTESTS: Says University Forsakes Freedom for Race Oppression,” New York Times, January 13, 1923, https://nyti.ms/3LouWpE.

-

Andrew Schlesinger, Veritas: Harvard College and the American Experience, (Chicago, IL: I.R. Dee, 2005), 162.

-

“NEGRO GRADUATE PROTESTS,” New York Times.

-

President Lowell to Arthur Warner, November 12, 1921, box 171, folder 981, Freshman Dormitories, Records of the President of Harvard University, Abbott Lawrence Lowell, [Series 1919-1922] UAI 5.160, Harvard University Archives.

-

For untitled and undated drafts addressing “the negro question,” c. October 1922, see Freshman Dormitories, box 171, folder 981, Records of the President of Harvard University, Abbott Lawrence Lowell, [Series 1919-1922] UAI 5.160, Harvard University Archives.

-

R. C. Benchley to [Abbott Lawrence] Lowell, June 15, 1922, box 171, unspecified: folder 981, Freshman Dormitories, Records of the President of Harvard University, Abbott Lawrence Lowell, 1909-1933: folder lists, UAI 5.160, Harvard University Archives. Concerning the racial makeup of the committee, see Wolters, “The New Negro on Campus,” 199 and Louis Marshall, “Alfred Jaretzki,” Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society 31 (1928): 266-268.

-

Wolters, “The New Negro on Campus,” 199.

-

“Memorial to the Corporation” (1922), Harvard University Archives.

-

Painter, “Jim Crow at Harvard: 1923,” 628-634.

-

Schlesinger, Veritas, 165. In his initial response, Lowell explained his view of the compulsory nature of the freshman halls as a special case and wrote, “I am sure you will understand why, from the beginning, we have not thought it possible to compel men of different races to reside together.” Bruce’s response to Lowell was one of “shock” that such a well-cultivated young man as his son would be discriminated against for his race alone. “Not race, but culture, I had supposed, is the basis of sound nationality,” wrote Bruce. See Harvard Alumni Association and Associated Harvard Clubs, “Colored Students at Harvard,” Harvard Alumni Bulletin 25, no. 16 (January 18, 1923): 456-457. See also “Colored Students in the Freshman Halls,” Harvard Alumni Bulletin 25, no. 18 (February 1, 1923): 527-533.

-

“NEGRO GRADUATE PROTESTS,” New York Times.

-

“Attacks Harvard On Negro Question,” New York Times.

-

Wolters, “The New Negro on Campus,” 201.

-

Harvard Alumni Association and Associated Harvard Clubs, “Negroes in the Freshman Halls,” Harvard Alumni Bulletin 25, no. 28 (April 12, 1923): 830.

-

Synnott, The Half-Opened Door, 48.

-

Keller and Keller, Making Harvard Modern, 61.

-

Synnott, The Half-Opened Door, 49.

-

Courtney Suciu, “The NAACP’s Anti-Lynching Campaign,” ProQuest (blog), February 13, 2019, https://about.proquest.com/en/blog/2019/the-naacps-anti-lynching-campaign/.

-

The scholar William Leo Hansberry was also a member of the class of 1921. So too was Edward O. Gourdin, though he was in Paris competing at the Olympics on this date. See Daphne Abeel, “Edward Orval Gourdin: Brief Life of a Breaker of Barriers, 1897-1966,” Harvard Magazine, November 1997, https://harvardmagazine.com/sites/default/files/html/1997/11/vita.html.

The Cambridge Chronicle reported on a Klan meeting in North Cambridge in October 1922. See “The Ku Klux Klan Holds Meeting in North Cambridge, Tuesday Night,” The Cambridge Chronicle, October 7, 1922, https://cambridge.dlconsulting.com/?a=d&d=Chronicle19221007-01.2.2.

-

Boston Herald, June 18, 1924, as quoted in Harvard College Class of 1921: Report of the Triennial Reunion Report, June 1924, p. 33, Secretary’s Reports, Class Material, Class of 1921, HUD 321.4, Harvard University Archives.

A similar incident occurred at Princeton the same year. See John S. Weeren. “Shades of the Ku Klux Klan: The Class of 1920’s ‘Fiery Fourth’,” The Princeton University Library Chronicle 71, no. 1 (Autumn 2009): 89-98.

-

The Twenty-First Gun 2, no. 2 (May 6, 1927): 7, Class Material, Class of 1921, HUD 321.4, Harvard University Archives.

-

See, for example, Harvard Lampoon 84, no. 9 (January 18, 1923), box 17, The Harvard Lampoon, HUK 510 Copy A, Harvard University Archives, and “Klan Fills Cambridge With Horrible Manifestations--Opposes Quinn for Mayor--Names Kopey Its Klandidate,” Harvard Crimson, November 1, 1923, https://www.thecrimson.com/article/1923/11/1/klan-fills-cambridge-with-horrible-manifestations-opposes/.

-

“The Krimson K. K. K.,” Harvard Crimson, October 22, 1923, https://www.thecrimson.com/article/1923/10/22/the-krimson-k-k-k-pto/; “Ku Klux Klan At Harvard Awaits Moment To Strike,” Harvard Crimson, October 22, 1923; James Weldon Johnson to President and Board of Overseers of Harvard University, October 23, 1923, telegram, box 201, folder 507, Ku Klux Klan, Records of the President of Harvard University, Abbott Lawrence Lowell, UAI 5.160, Harvard University Archives. See also “More Facts Appear On Harvard Klan: Some Klansmen Seeking to Reorganize in University--College Rulings an Obstacle--Evasion Likely,” Harvard Crimson, October 25, 1923, https://www.thecrimson.com/article/1923/10/25/more-facts-appear-on-harvard-klan/; “Kollegiate Klansman,” Harvard Crimson, October 25, 1923, https://www.thecrimson.com/article/1923/10/25/kollegiate-klansmen-pdefinite-information-that-harvard/.

-

See Sollors et al., Blacks at Harvard, xxx.

-

Synnott, The Half-Opened Door, 47; on his exclusion from the glee club and social marginalization, see W. E. B. Du Bois, “A Negro Student at Harvard,” 439-458.