A Legacy of African American Resistance

This report uncovers Harvard’s complicity with slavery and its legacies, and in so doing, also recognizes as a part of the University’s history enslaved people of African and Native descent whose contributions have been overlooked. These individuals include Titus, Venus, Juba, and Bilhah, whose service in bondage to Presidents Wadsworth and Holyoke and their families supported their leadership of the University and enabled their lives as scholars.Go to footnote 82 detail It also includes Cuba, once owned by Penelope Royall Vassall—sister of the slaveholding benefactor of Harvard Law School—as well as Darby Vassall, the son of Cuba and her husband, Anthony (Tony). Darby Vassall went on to play an important role in Boston’s free Black community, and his life and activism illustrate a critically important theme embedded in this report: Black resilience, agency, and achievement in the face of persistent discrimination.

The theme of Black resilience, agency, and achievement is especially relevant to the report’s discussion of late 19th- and 20th-century vestiges of slavery at Harvard. During the era of segregation, small numbers of African American students arrived on campus. Despite the oftentimes inhospitable learning environment, these Black Harvardians made vital contributions to the nationwide struggle against slavery’s legacies. A few examples make the point.

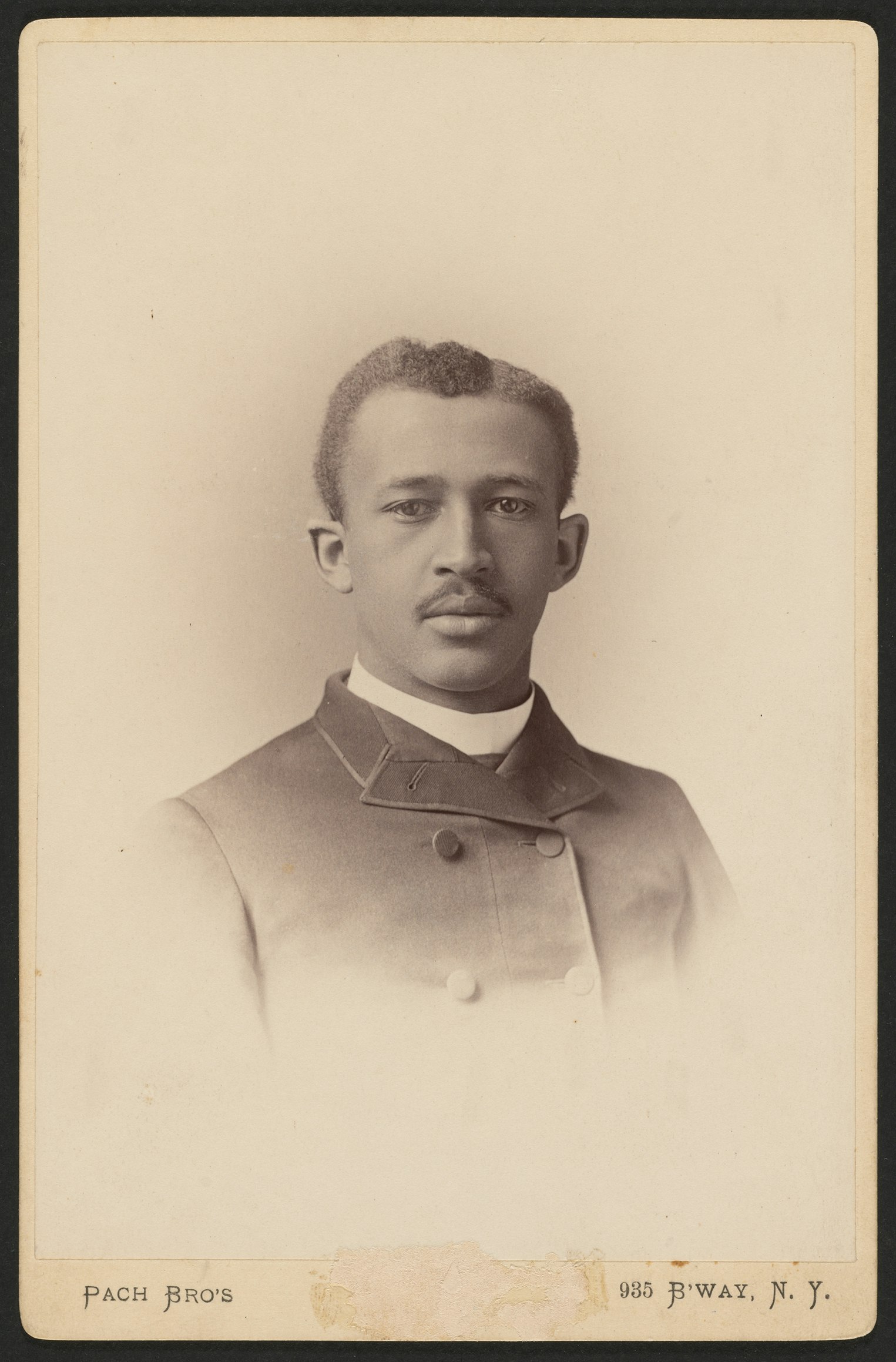

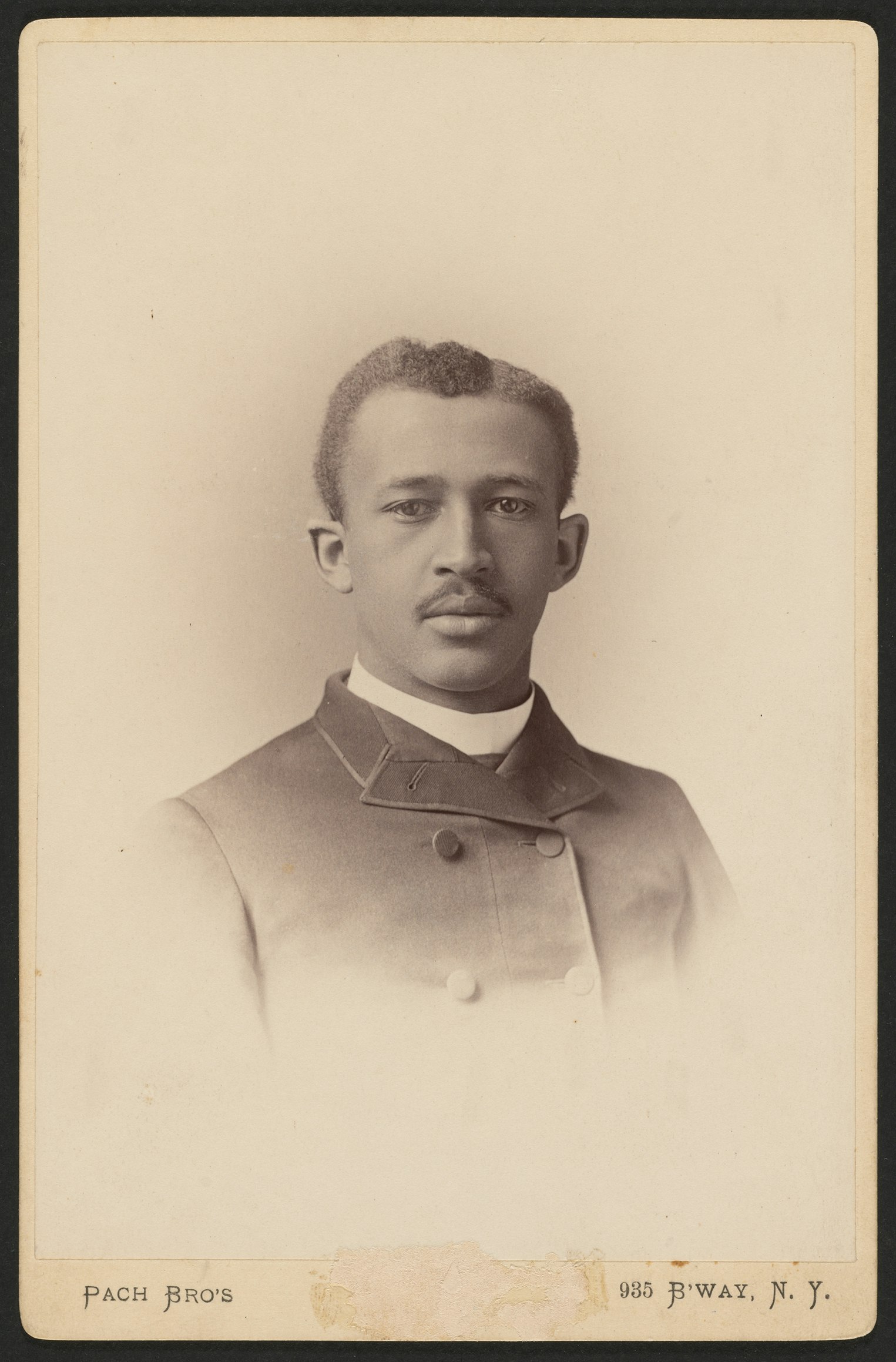

W. E. B. Du Bois, a graduate of Harvard College (1890) and the first African American to earn a PhD from Harvard (1895), made towering intellectual contributions even as he experienced racism on and off campus. Building on work he had first explored as a Harvard student, Du Bois, as a faculty member at HBCUs—first at Wilberforce University in Ohio and then at Atlanta University—described and analyzed the persistent problem of the American “color line.”Go to footnote 83 detail Moreover, Du Bois and the Black Harvard graduate William Monroe Trotter (AB 1895; AM 1896) cofounded the Niagara Movement, the precursor to the nation’s oldest civil rights organization, the NAACP.Go to footnote 84 detail

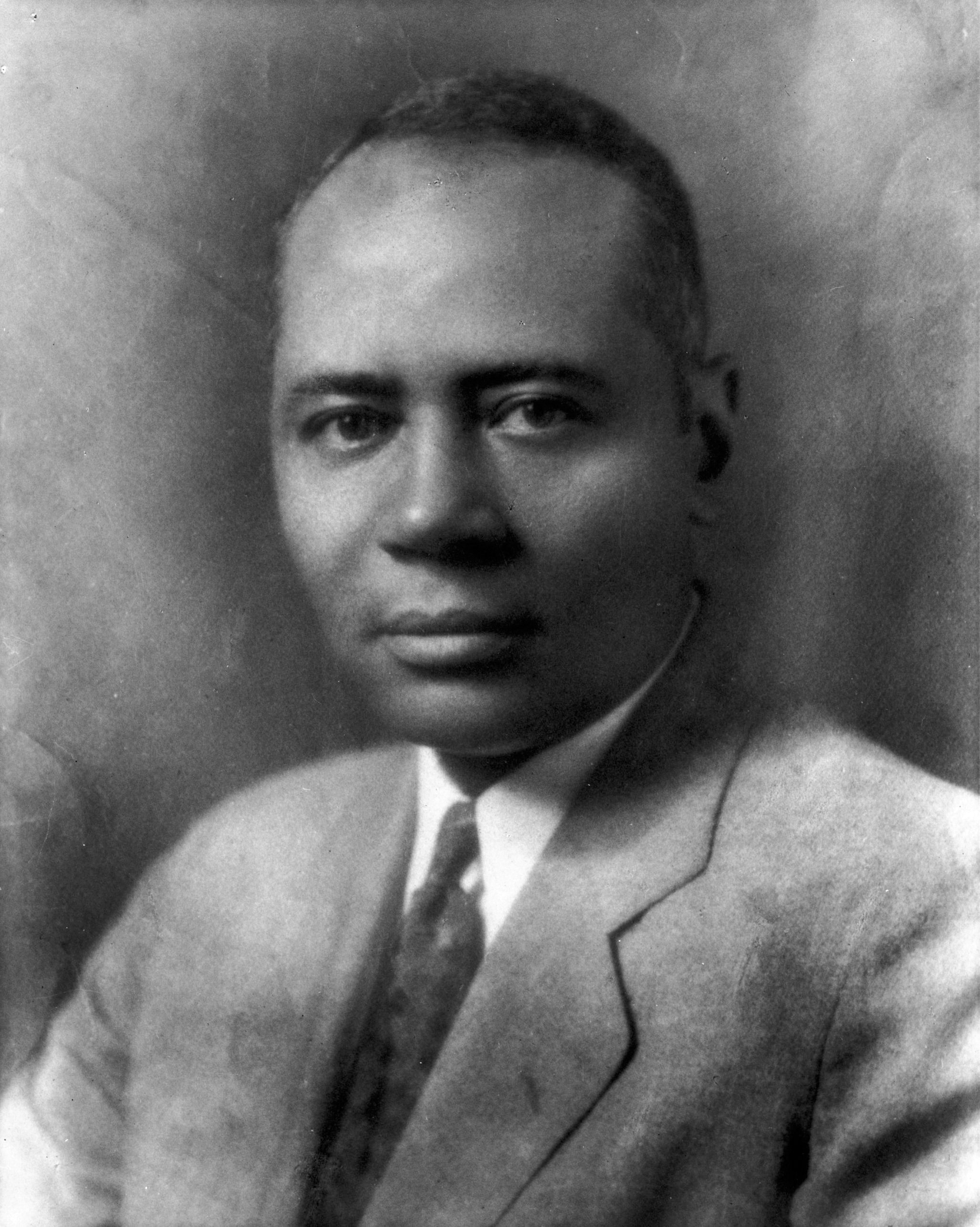

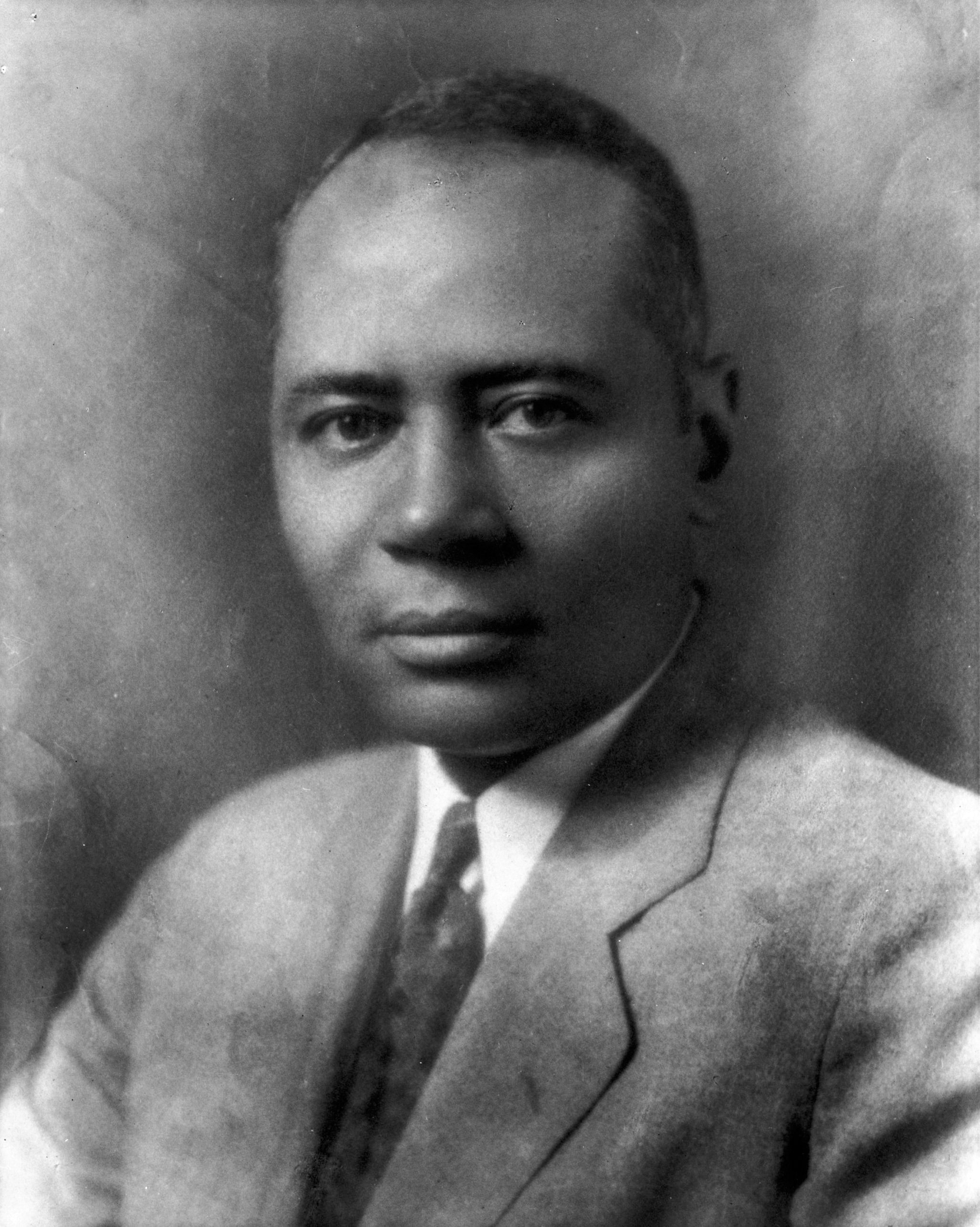

Charles Hamilton Houston (LLB 1922; SJD 1923), the first African American editor of the Harvard Law Review, went on to become the vice-dean of Howard Law SchoolGo to footnote 85 detail and special counsel to the NAACP. A brilliant lawyer who was called “the man who killed Jim Crow,” Houston laid the legal groundwork for the reshaping of American law and society during the Civil Rights Movement.Go to footnote 86 detail

And Eva Beatrice Dykes, the first summa cum laude graduate of Howard University, completed a master’s degree and, in 1921, earned a PhD from Radcliffe—the first African American woman to complete the requirements for a doctorate in the United States and one of three Black women in the country to complete a PhD that year. A daughter of enslaved people, Dykes went on to an illustrious career as a professor of English at historically Black colleges, first at Howard and then at Oakwood University.Go to footnote 87 detail But when she had first sought admission to graduate studies at Radcliffe College,Go to footnote 88 detail administrators were unimpressed by her credential earned at the historically Black Howard, and they required a do-over; Dykes, like some other HBCU graduates who enrolled at Harvard and Radcliffe, was forced to earn a second bachelor’s degree. She did, graduating magna cum laude and Phi Beta Kappa in 1917.Go to footnote 735 detail

The efforts of these African Americans, with support from white allies, including some at Harvard,Go to footnote 89 detail gave rise to Brown v. Board of Education, the landmark 1954 US Supreme Court decision that outlawed state-sponsored school segregation and was “nothing short of a reconsecration of American ideals.”Go to footnote 90 detail Brown and the Civil Rights Movement prepared the way for passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, groundbreaking legislation that barred discrimination in key American institutions and helped create the more equitable world in which we live today.Go to footnote 91 detail

These individuals, too, represent Harvard. They are important actors in the University’s history and in the making of a more perfect American union; and they must be made visible in this report. Through struggles against racial oppression and for human freedom, these graduates created legacies of professional leadership and civic engagement, and they made profound legal and social changes. The achievements of Black graduates of Harvard illustrate the entwining of the nation’s racial progress and access to a Harvard, and a Radcliffe, education.

Footnotes

-

See Beckert et al., Harvard and Slavery, 9–10.

-

See, for example, W. E. B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2015); W. E. B. Du Bois, The Problem of the Color Line at the Turn of the Twentieth Century: The Essential Early Essays (New York, NY: Fordham Scholarship Online, 2015); W. E. B. Du Bois, The Negro (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014); see generally David Levering Lewis, W. E. B. Du Bois, 1868-1919: Biography of a Race (New York, NY: H. Holt, 1993) and W. E. B. Du Bois: The Fight for Equality and the American Century, 1919-1963 (New York, NY: Holt and Company, 2000).

-

See Patricia Sullivan, Lift Every Voice: The NAACP and the Making of the Civil Rights Movement (New York, NY: The New Press, 2010); see also Kerri K. Greenidge, Black Radical: The Life and Times of William Monroe Trotter (New York, NY: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2020).

-

Although formally vice-dean, Houston “had the responsibilities of a dean” and was Howard Law School’s “dean in all but title,” according to a Howard University profile. See Steven D. Jamar, “Charles Hamilton Houston (1895-1950),” Brown@50, Howard University School of Law, accessed February 17, 2022, http://law.howard.edu/brownat50/BrownBios/BioCharlesHHouston.html.

-

See Genna Rae McNeil, Groundwork: Charles Hamilton Houston and the Struggle for Civil Rights (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1984).

-

Sollors et al., eds., Blacks at Harvard, 3.

-

On the history of Radcliffe College, see “History,” Harvard Radcliffe Institute, accessed November 5, 2021, https://www.radcliffe.harvard.edu/about-the-institute/history; see also Sally Schwager, “Taking up the Challenge: The Origins of Radcliffe,” in Ulrich, Yards and Gates, 87–116.

-

“Eva Dykes, Transcript,” Interviews of the Black Women Oral History Project, 1976–1981, OH- 31; T-32, Schlesinger Library, Harvard Radcliffe Institute, i–iii, https://nrs.lib.harvard.edu/urn-3:rad.schl:10041689. Dykes was also profiled in Sollors et al., Blacks at Harvard, 160–167.

-

For example, Harvard Law Professor Felix Frankfurter, a Jewish immigrant to the United States from Austria, who went on to become Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, mentored Houston. See McNeil, Groundwork, 53, 63–64. Du Bois counted William James and Albert Bushnell Hart as mentors. See Sollors et al., eds., Blacks at Harvard, xx, 5.

-

Richard Kluger, Simple Justice: The History of Brown v. Board of Education and Black America’s Struggle for Equality (New York, NY: Vintage, 2004), 713.

-

William T. Martin Riches, The Civil Rights Movement: Struggle and Resistance (New York, NY: Red Globe Press, 2017).