W.E.B. Du Bois

Class of 1895

W.E.B. Du Bois

W.E.B. Du Bois, the first Black person to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard, used his talent and intellect to pave a path toward racial uplift.

School: Harvard College

Degree: A.B., A.M., Ph.D.

Area of Impact: Education, Scholarship, Civil Rights, Sociology

HBCU Affiliation: Clark Atlanta University, Fisk University, Wilberforce University

Much has been written about W.E.B. Du Bois and his tremendous impact as a scholar and activist. His role in cofounding the NAACP — the nation’s oldest civil rights organization — was perhaps his most profound act of resistance to the marginalization of Black people in the United States. Under the aegis of that organization and its lawyers, Black Americans fought against discrimination in the politics, housing, public accommodations, the criminal justice system, and education.

Du Bois traveled and spoke extensively on behalf of the NAACP, advocating for full equality for Black Americans. All American News, Inc. All-American news. 1945-07, no. 3. “Dr. Du Bois at Denver”. Produced by William D. Alexander, E. M. Glucksman, and Claude Barnett. July 1945/Library of Congress, Motion Picture, Broadcasting, and Recorded Sound Division (Public Domain)

Embracing “the companionship of those of my own color”

Born three years after the end of the Civil War, Du Bois grew up in predominantly white Great Barrington, Massachusetts, a small, rural town in the western part of the state. His childhood in Great Barrington was a central influence in his life, as was his mother, Mary, who cultivated young Du Bois’s understanding of what it meant to be Black in America.

In 1885, Du Bois left home for the historically Black Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee. There, for the first time in his life, Du Bois felt the embrace of a large Black community.

He also witnessed firsthand a level of overt racism he had not encountered before. He recalled decades later in a convocation address at Atlanta University (today Clark Atlanta University),

It was to me an extraordinary experience. I was thrilled to be for the first time among so many people of my own color or rather of such various and such extraordinary colors, which I had not seen before, but who seemed close bound to me by new and exciting ties. […] The three years here were years of growth, strength and expanding ambition. I learned new things about the world. I came in contact for the first time with a sort of violence that I had never realized in New England.

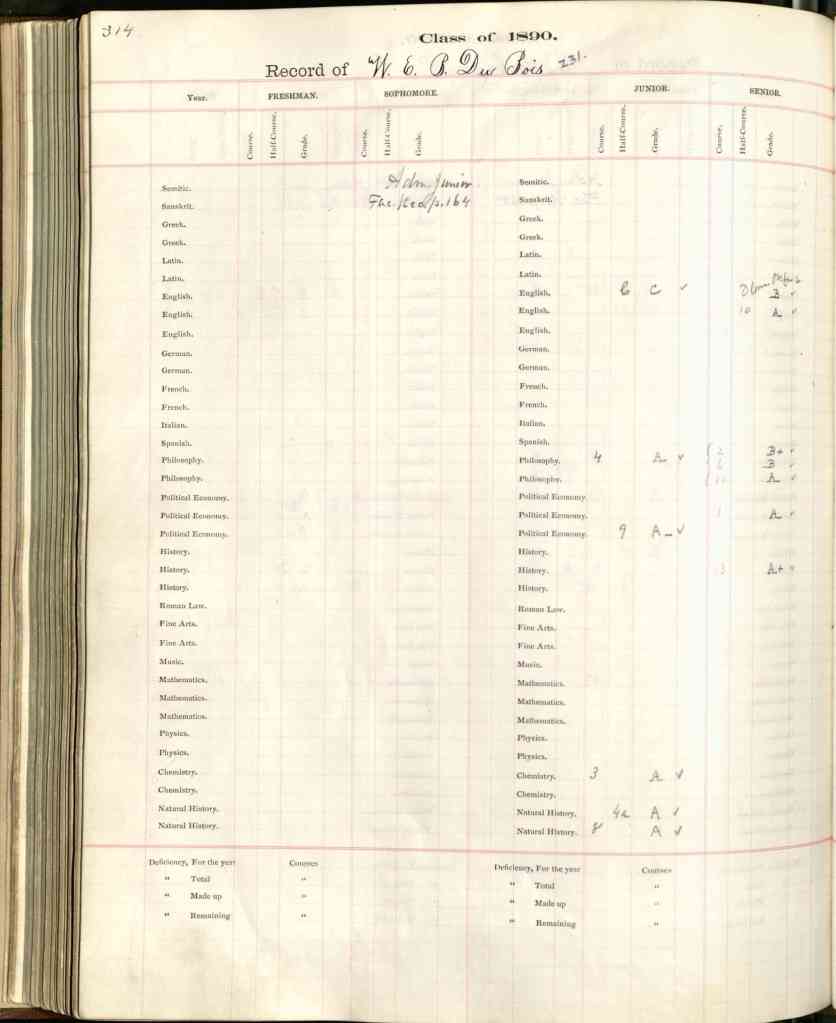

Upon graduation from Fisk and with financial assistance from his family and supporters as well as Harvard, Du Bois headed to Cambridge in 1888 with the goal of earning a Ph.D. in philosophy.

“I was in Harvard, but not of it”

At Harvard, Du Bois was thrilled to have access to professors renowned in their fields and to the University’s impressive facilities. But because inadequate resources and racism prohibited historically Black colleges and universities from being nationally accredited, Du Bois was forced to enter Harvard as a junior and complete a second bachelor’s degree before continuing on to graduate studies. He had no illusions about how he would be received on campus. In his 1960 essay “A Negro Student at Harvard at the End of the 19th Century,” he wrote,

To make my own attitude toward the Harvard of that day clear, it must be remembered that I went to Harvard as a Negro, not simply by birth, but recognizing myself as a member of a segregated caste whose situation I accepted. But I was determined to work from within that caste to find my way out.

He famously reflected that he was “in Harvard but not of it.”

Unable to afford to live on campus, Du Bois sought private lodging and found a room that suited both his taste and his budget in a house owned by a “colored woman from Nova Scotia” located a mile from campus at 20 Flagg Street. “My room is, for a college man’s abode very ordinary, indeed,” he later recalled writing at the time, but it was “pleasantly situated” on the second floor with a bay window and enough room to start a library. “In this commonplace den I am quite content,” Du Bois said of what would be his home for four years.

Du Bois was deliberate in his choice not to pursue close relationships with many of his white fellow students, whom he believed had little desire to befriend him. As he noted in a graduate school paper titled “Harvard and the South,” the “Northern student of Southern affairs . . . wavers between calling the whites rascals, or the Negroes idiots.” He sought to challenge his classmates’ stereotypes, arguing: “I respectfully submit that he need do neither.”

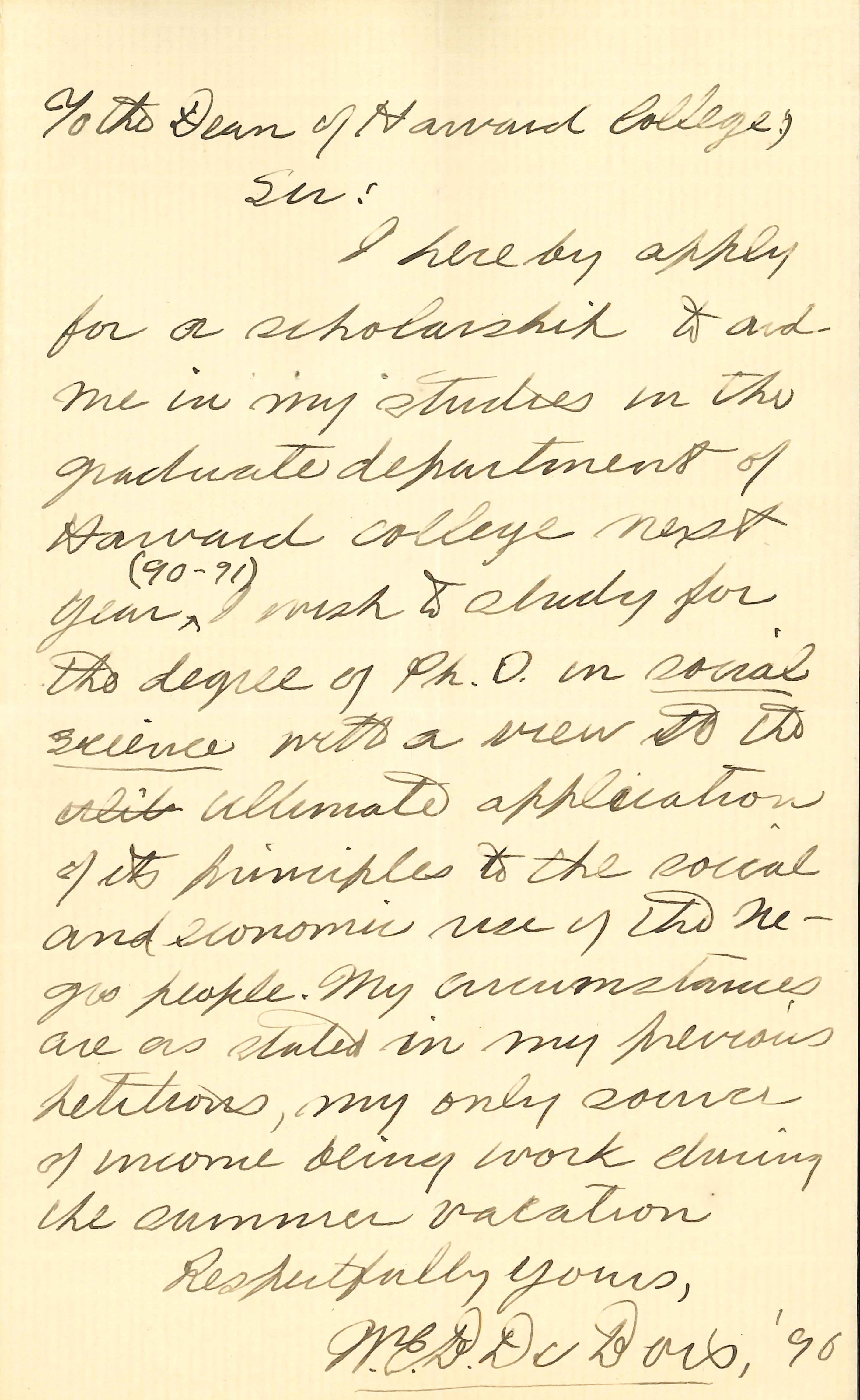

Open and scroll to read the note transcript

Sir:

I hereby apply for a scholarship to aid me in my studies in the graduate department of Harvard College next year ^(90–91) I wish to study for the degree of Ph. D. in [discipline underlined] social science with a view to the [next word struck through] ulit ultimate application of its principles to the social and economic rise of the negro people. My circumstances are as stated in my previous petitions, my only source of income being work during the summer vacation

Respectfully yours,

[signature underlined] W.E.B. Du Bois, ’90

[end of page]

Du Bois wrote in 1890 to request much-needed financial aid from the University to support him while a student at Harvard. Although he received some funding, he was still unable to afford a room “in the college yard in the old and venerable buildings […] under the magnificent elms.” W.E.B. Du Bois student folder. Harvard College Student Folders, ca. 1890–1995. UAIII 15.88.10 Box 120 VT/Harvard University Archives

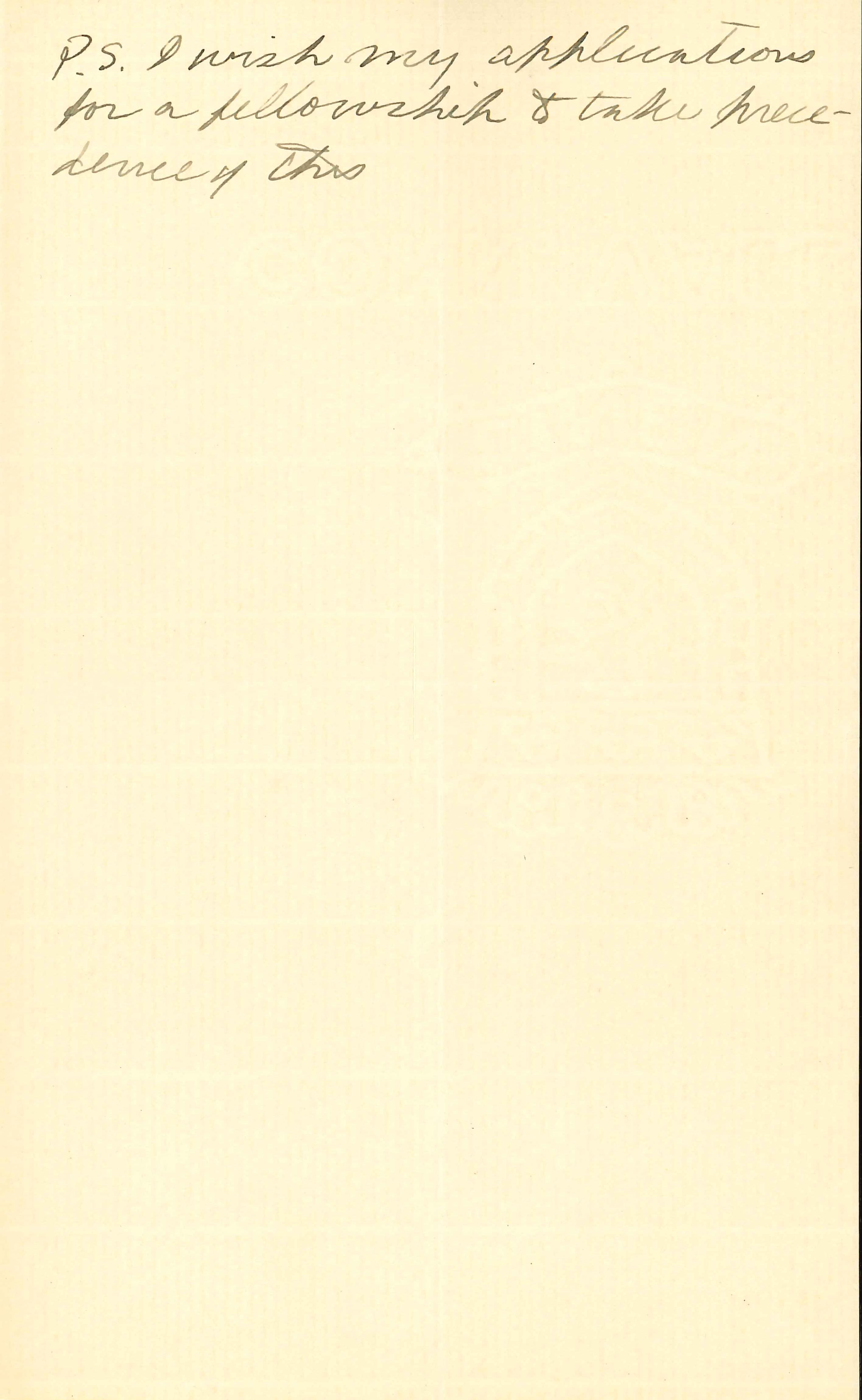

Open and scroll to read the note transcript

P.S. I wish my applications for a fellowship to take precedence of this

[end of page; end of document]

Du Bois was clear that he preferred more prestigious merit-based fellowships to need-based financial aid. W.E.B. Du Bois student folder. Harvard College Student Folders, ca. 1890–1995. UAIII 15.88.10 Box 120 VT/Harvard University Archives

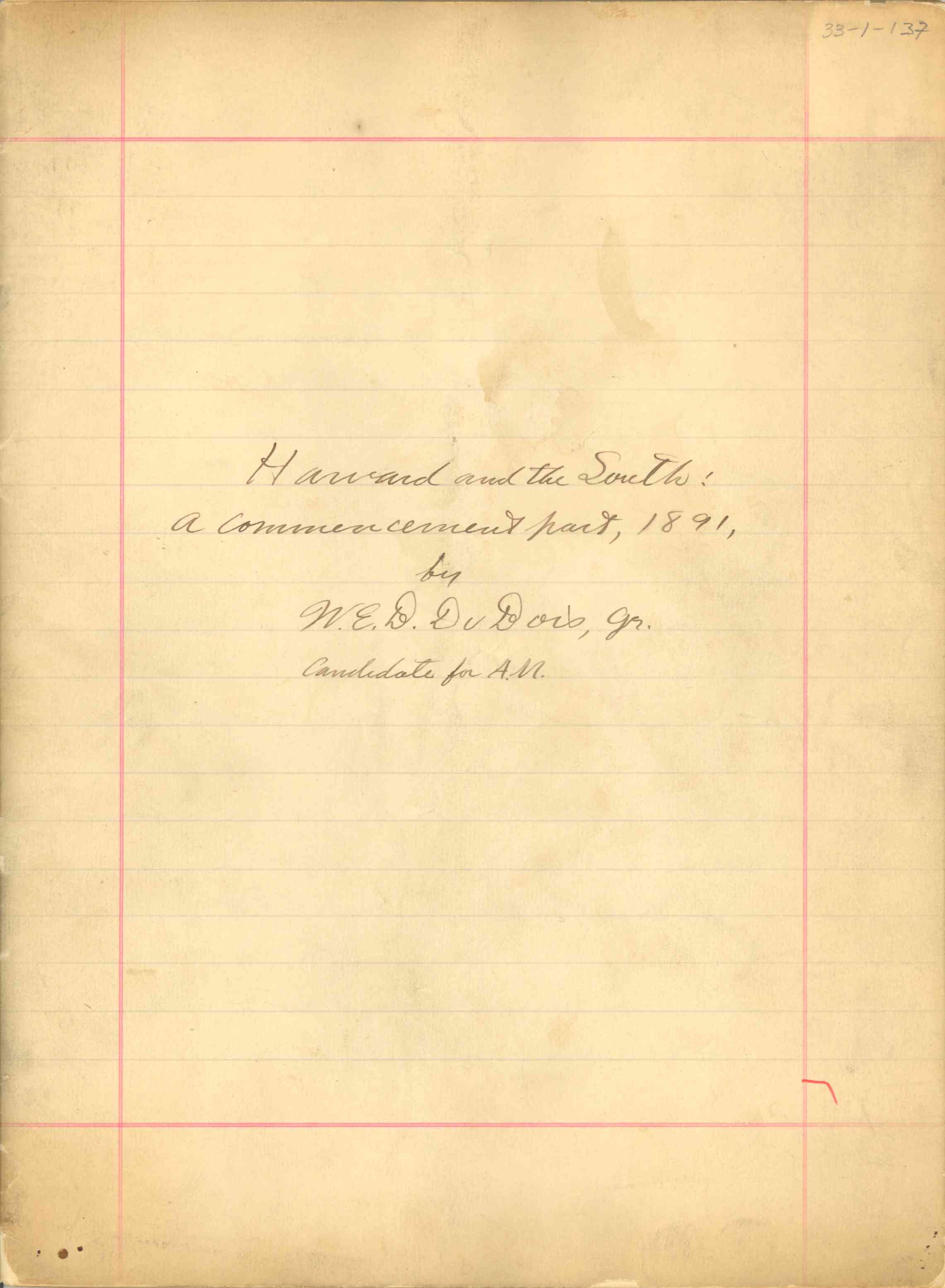

Open and scroll to read the paper transcript

[handwritten in pencil in top right corner] 33-1-137

[handwritten in ink; centered vertically and horizontally on the page]

Harvard and the South:

A commencement part, 1891,

By

W.E.B. Du Bois, Jr.

Candidate for AM

[end of document]

In a graduate school paper titled “Harvard and the South,” Du Bois noted that the “Northern student of Southern affairs […] wavers between calling the whites rascals, or the Negroes idiots.” Challenging his classmates’ stereotypes, he argued: “I respectfully submit that he need do neither.” W.E.B. Du Bois Papers/Robert S. Cox Special Collections and University Archives Research Center, UMass Amherst Libraries

Had he matriculated at Harvard immediately after graduating from his integrated high school in Great Barrington, and not experienced racial segregation during his years at Fisk, he wrote, he would have sought friendships with white students “and been disappointed and embittered by a discovery of social limitations to which I had not been used.” Instead, he largely made friends with Black students at Harvard and other local institutions and with the “colored folk of Boston and surrounding towns.”

With them I led a happy and inspiring life. There were among them many educated and well-to-do folk, many young people studying or planning to study, many charming young women. We met and ate, danced and argued, and planned a new world.

This approach was “self-protective coloration, with perhaps an inferiority complex, but with belief in the ability and future of black folk.” And while Du Bois’s fellow Black students tended to be firmly on the side of integration, Du Bois was steadfast in his “dream of a self-sufficient Negro culture, even in America.”

Du Bois did not completely isolate himself within Harvard, however. He joined the Philosophical Club and the Foxcroft dining club, the latter providing a place where students who lived off campus could study during the day and get inexpensive meals. A singer, he tried out for the glee club but was denied a place. The club members reasoned that it would be too difficult to tour nationally, at a time when public accommodations in the South were segregated, with a Black member.

Du Bois excelled academically and got along well with his professors, some of whom, such as the historian Albert Bushnell Hart and philosopher and psychologist William James, befriended him and invited him into their homes. While always aware of the power dynamics between white professor and Black student, Du Bois observed, “they were on the whole glad to receive a serious student, to whom extracurricular activities were not of paramount importance, and one who in a general way knew what he wanted.”

To support himself during his studies, Du Bois participated in oratory competitions. In his first year at Harvard, he won second place in the competition for the Boylston Prize in Elocution. First prize went to Clement G. Morgan, another Black student who, because of this victory — and despite what Du Bois described as the outrage of whites across the nation — was selected to be class orator.

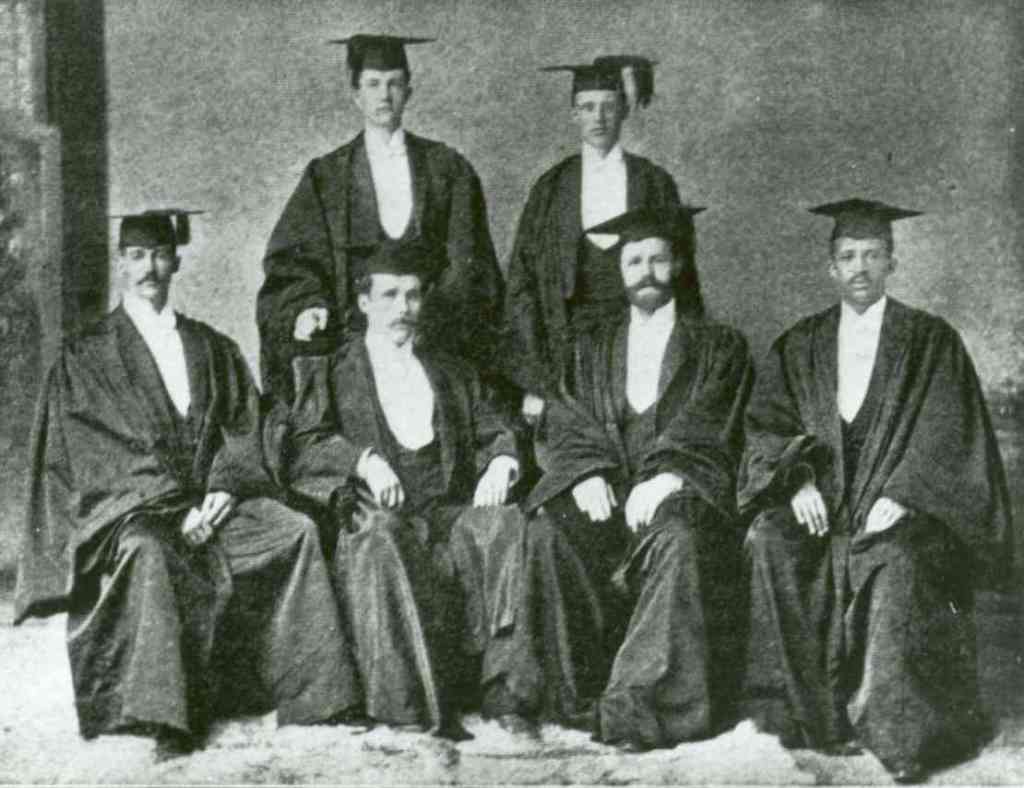

According to Du Bois, Morgan’s success inspired several other colleges to confer similar honors on their Black students. The following year, it was Du Bois who took first place in the Boylston competition. He was also one of five seniors chosen to speak at Commencement. Morgan was also initially selected, but after a faculty member moved to consult the Harvard Corporation as to whether it was appropriate to bestow such an honor on multiple Black students, the Corporation limited the number of Black speakers to one. Du Bois delivered a bold address on Jefferson Davis “with the deliberate intent of facing Harvard and the nation with a discussion of slavery as illustrated in the person of the president of the Confederate States of America.”

Bishop Henry C. Potter wrote in the Boston Herald after hearing Du Bois’s address, “Here is what an historic race can do if they have a clear field, a high purpose, and a resolute will.” Potter was not alone. The audience’s reaction was so positive that Du Bois later wrote that he “walked home on pink clouds of glory.”

What Du Bois wanted above all was to become a philosopher. And he believed that studying at a German university was a prerequisite for achieving that lofty goal and gaining recognition in the rarefied field.

It was in Berlin, DuBois wrote, “where I first met white folk who treated me as a human being.”

No Was Not an Option

Without viable prospects for Harvard scholarships or fellowships to study in Europe, Du Bois learned that the John F. Slater Fund, headed by former U.S. President Rutherford B. Hayes, was seeking “colored men worth educating,” to fund their studies in the United States and abroad. Du Bois applied, but Hayes responded that what Du Bois had read about the program was incorrect; the organization had provided scholarships in the past, but no longer.

Undeterred, Du Bois challenged Hayes in a second letter,

I find men willing to help me thro’ cheap theological schools, I find men willing to help me use my hands before I have got my brains in working order, I have an abundance of good wishes on hand, but I never found a man willing to help me get a Harvard Ph.D.

He wrote letter after letter, and his persistence paid off. The following year, the Slater Fund awarded him a $750 fellowship (half gift, half loan) for a year of study at the University of Berlin. Du Bois later wrote that, after he received word that he could study abroad: “I remember rushing down to New York and talking with ex-President Hayes in the old Astor House and emerging on air. I saw an especially delectable shirt in a shop window. I went in and asked about it. It cost three dollars, which was about four times as much as I had ever paid for a shirt in my life, but I bought it.”

In 1895, Du Bois famously became the first Black person to earn a Ph.D. (in history, rather than philosophy) from Harvard. He would go on to become one of the most influential figures in American history, producing seminal scholarship on Black history and the Black experience in the United States, co-founding the Niagara Movement and its successor the NAACP and serving as a leading voice in the fight for equality until his death in 1963.

Selected Sources

“W.E.B. Du Bois.” The Report of the Presidential Committee on Harvard & the Legacy of Slavery. Harvard Radcliffe Institute. Accessed July 10, 2023.

Du Bois, W.E.B.. W.E.B. Du Bois Speaks: Speeches and Addresses, 1920–1963. Edited by Philip S. Foner. New York: Pathfinder, 1970. Transcription available online via archive.org.

Du Bois, W.E.B.. “A Negro Student at Harvard at the End of the 19th Century.” The Massachusetts Review 1, no. 3 (Spring 1960): 439–458.

Du Bois, W.E.B., and Moses. Asch. W.E.B. Du Bois: A Recorded Autobiography. n.p.: Folkways Records FH 5511, 1961.

Du Bois, W.E.B.. The Autobiography of W.E.B. Du Bois: A Soliloquy on Viewing My Life from the Last Decade of Its First Century. New York, NY: International Publishers, 1968.

Lewis, David Levering. W.E.B. Du Bois: A Biography. New York, NY: Henry Holt and Co., 2009.

More profiles

Charles Hamilton Houston

Known as “The Man Who Killed Jim Crow,” Charles Hamilton Houston was the first Black person to both serve on the Harvard Law Review and earn a Doctor of Juridical Science (S.J.D.) from Harvard Law…

Clement G. Morgan

In 1893, Clement Garnett Morgan became the first Black student to graduate from both Harvard College and Harvard Law School. He went on to make history as the first Black alderman in New England and…

Carter G. Woodson

Carter G. Woodson, known as “The Father of Black History,” was the second African American to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard University. He created Negro History Week — the forerunner to Black History Month —…