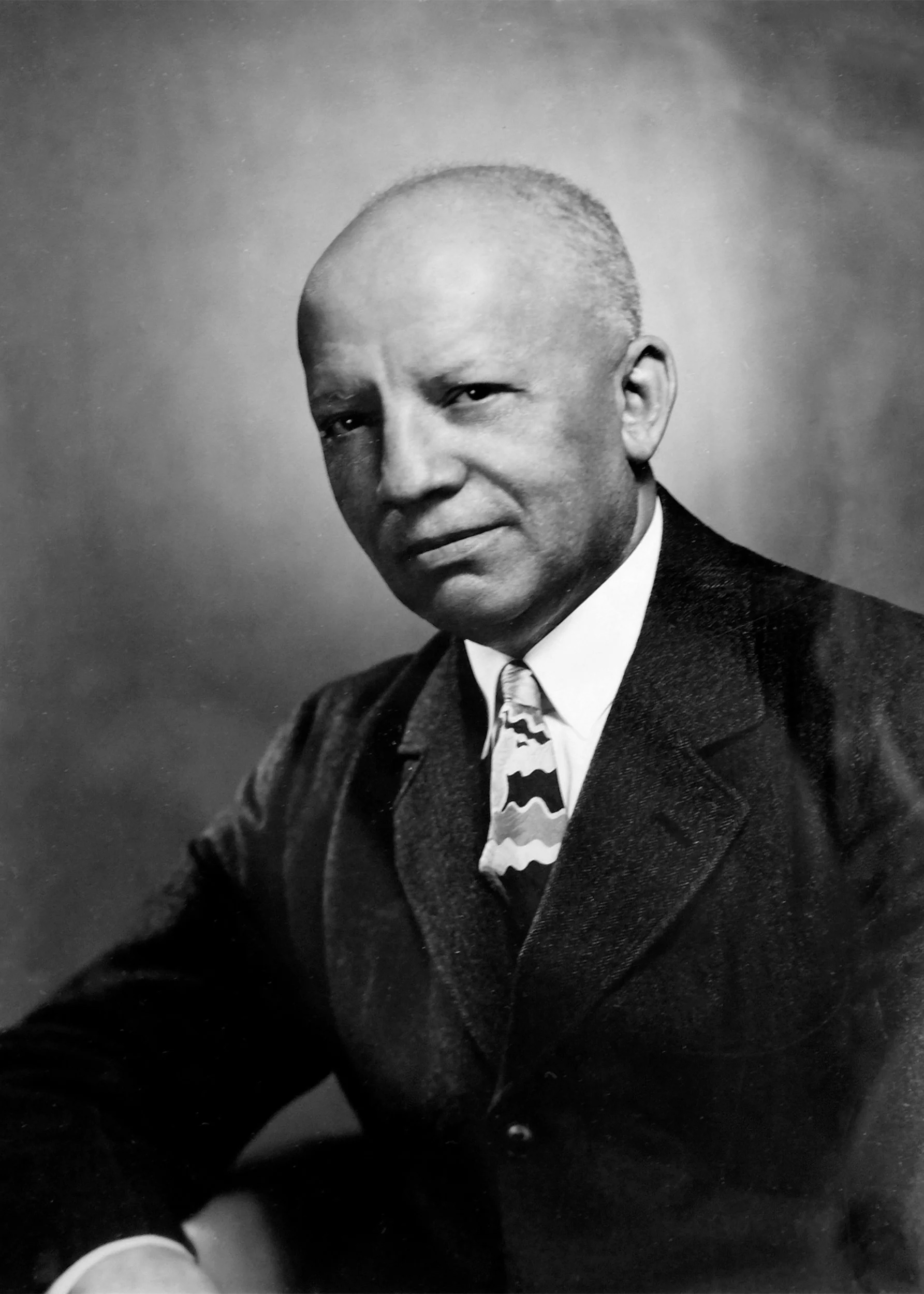

Carter G. Woodson

Class of 1912

Carter G. Woodson

Carter G. Woodson, known as “The Father of Black History,” was the second Black person to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard University. He created Negro History Week — the forerunner to Black History Month — and established the Association for the Study of African American Life and History.

School: Harvard College

Degree: Ph.D.

Area of Impact: Education, History, African and African American Studies

HBCU Affiliation: Howard University, West Virginia State University

A World Traveler and a Scholar

Carter Godwin Woodson was born on December 19, 1875, to formerly enslaved parents in New Canton, Virginia. As a young man, Woodson worked as a farm laborer and coal miner in Huntington, West Virginia, to contribute to the family finances while attending the all-Black Douglass High School. He then worked as a grade school teacher and principal in West Virginia, before matriculating at Berea College in Kentucky, where he earned a two-year B.L. degree in 1903 after years of balancing school with work as a high school teacher and principal. After graduating, he traveled to the Philippines where he spent several years as a school supervisor working under the U.S. War Department.

Open and scroll to read the article transcript

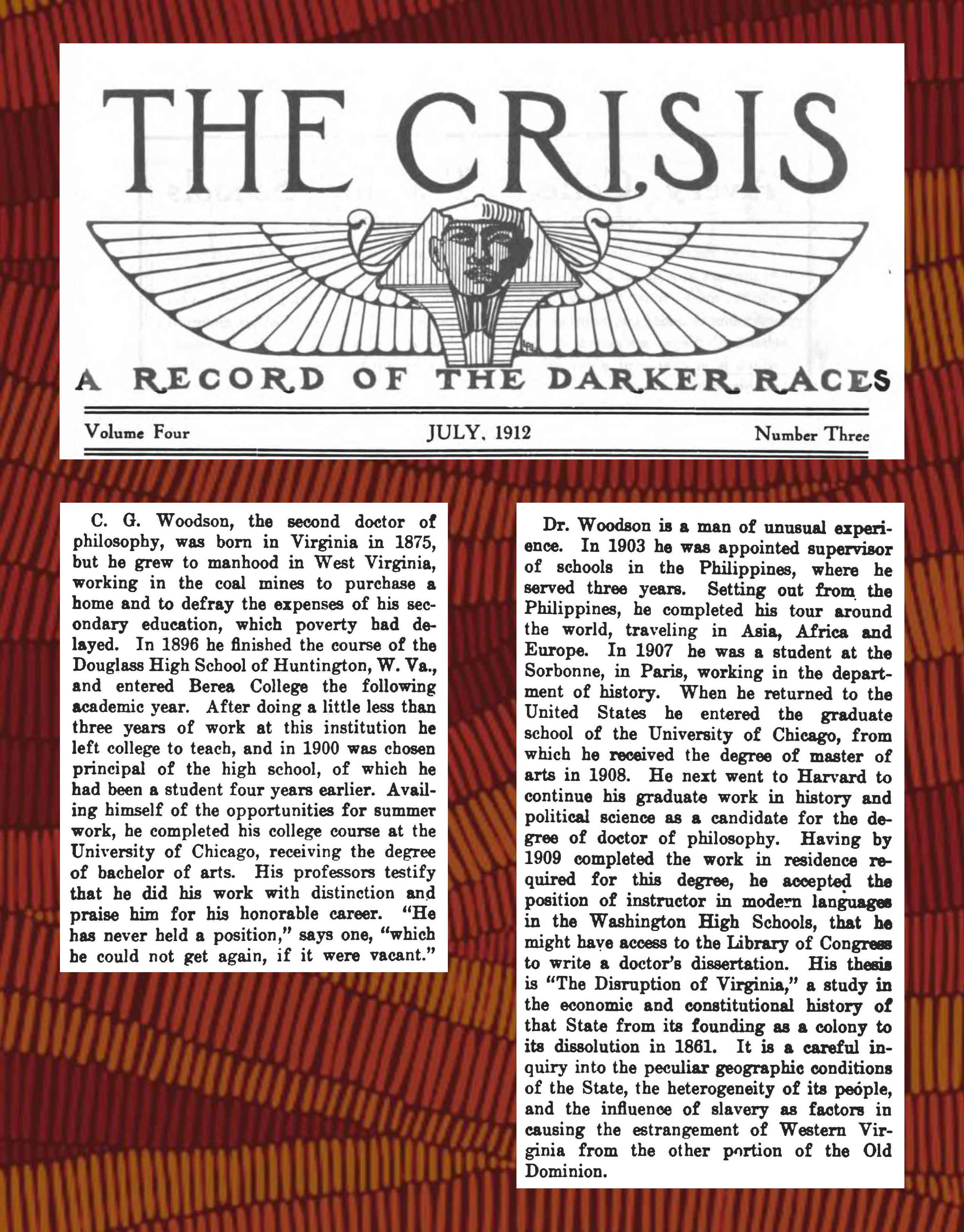

THE CRISIS

[line drawing of a dark-skinned face wearing an Egyptian pharaonic headdress and backed by two outspread wings]

A RECORD OF THE DARKER RACES

[double horizontal line divider]

Volume Four JULY, 1912 Number Three

[double horizontal line divider]

C. G. Woodson, the second doctor of philosophy, was born in Virginia in 1875, but he grew to manhood in West Virginia, working in the coal mines to purchase a home and to defray the expenses of his secondary education, which poverty had delayed. In 1896 he finished the course of the Douglass High School of Huntington, W. Va., and entered Berea College the following academic year. After doing a little less than three years of work at this institution he left college to teach, and in 1900 was chosen principal of the high school, of which he had been a student four years earlier. Availing himself of the opportunities for summer work, he completed his college course at the University of Chicago, receiving the degree of bachelor of arts. His professors testify that he did his work with distinction and praise him for his honorable career. “He has never held a position,” says one, “which he could not get again, if it were vacant.”

Dr. Woodson is a man of unusual experience. In 1903 he was appointed supervisor of schools in the Philippines, where he served three years. Setting out from the Philippines, he completed his tour around the world, traveling in Asia, Africa and Europe. In 1907 he was a student at the Sorbonne, in Paris, working in the department of history. When he returned to the United States he entered the graduate school of the University of Chicago, from which he received the degree of master of arts in 1908. He next went to Harvard to continue his graduate work in history and political science as a candidate for the doctor of philosophy. Having by 1909 completed the work in residence required for this degree, he accepted the position of instructor in modern languages in the Washington High Schools, that he might have access to the Library of Congress to write a doctor’s dissertation. His thesis is “The Disruption of Virginia,” a study in the economic and constitutional history of that State from its founding as a colony to its dissolution in 1861. It is a careful inquiry into the peculiar geographic conditions of the State, the heterogeneity of its people, and the influence of slavery as factors in causing the estrangement of Western Virginia from the other portion of the Old Dominion.

[end of excerpt]

The Crisis, the national magazine of the NAACP, named Woodson one of its “Men of the Month” in July 1912, alongside George E. Haynes of Columbia University — the only other Black person to complete a doctorate that year. The Crisis vol. 4, no. 3. July 1912/Public Domain

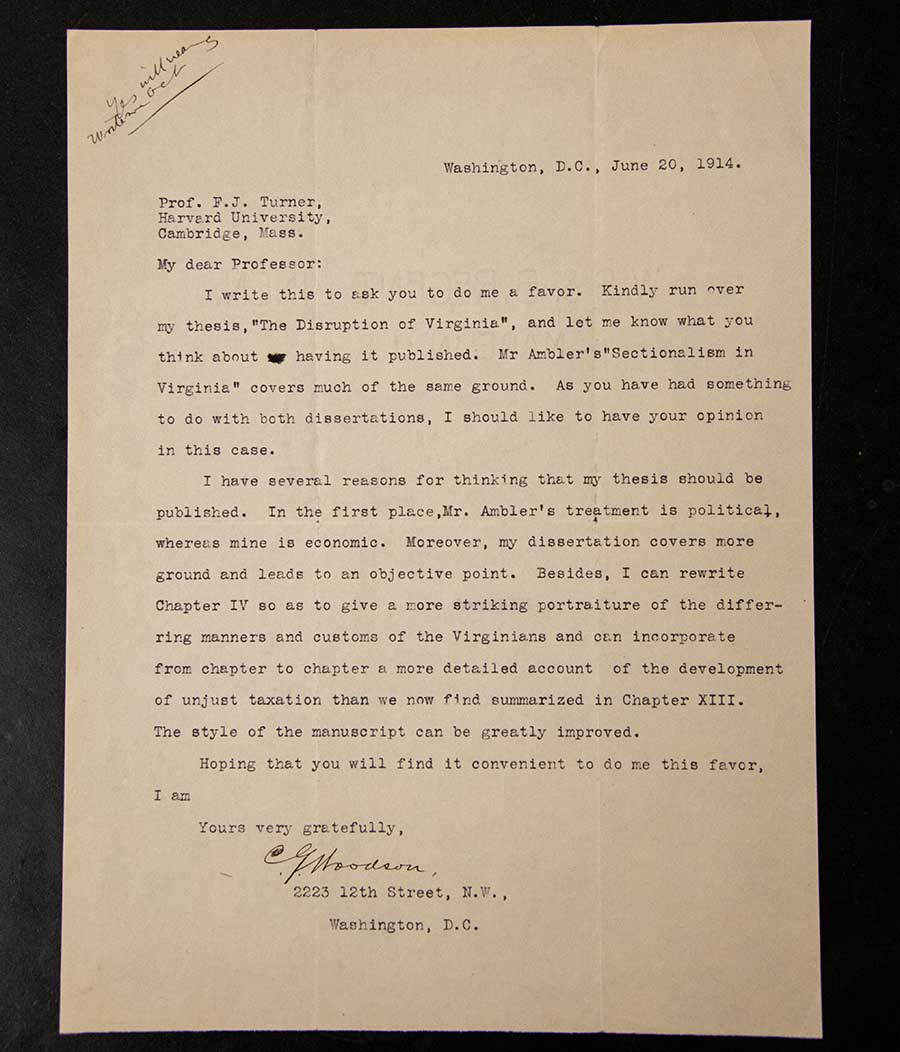

Despite the casual racism he faced from faculty — many of whom consistently minimized the role of Black Americans in U.S. history — Woodson successfully completed his Ph.D. in 1912. Carter G. Woodson. “The Disruption of Virginia.” Ph.D. dissertation. Harvard University. 1912/Harvard University Archives

Open and scroll to read the article transcript

[handwritten in top left corner] Yes will [illegible]

Washington, D.C., June 20, 1914.

Prof. F.J. Turner,

Harvard University,

Cambridge, Mass.

My dear Professor:

I write this to ask you to do me a favor. Kindly run over my thesis, “The Disruption of Virginia”, and let me know what you think about [letters marked out] having it published. Mr Ambler’s“Sectionalism in Virginia” covers much of the same ground. As you have had something to do with both dissertations, I should like to have your opinion in this case.

I have several reasons for thinking that my thesis should be published. In the first place,Mr. Ambler’s treatment is political, whereas mine is economic. Moreover, my dissertation covers more ground and leads to an objective point. Besides, I can rewrite Chapter IV so as to give a more striking portraiture of the differing manners and customs of the Virginians and can incorporate from chapter to chapter a more detailed account of the development of unjust taxation than we now find summarized in Chapter XIII. The style of the manuscript can be greatly improved.

Hoping that you will find it convenient to do me this favor,

I am

Yours very gratefully,

[handwritten in cursive] C.G.Woodson

2223 12th Street, N.W.,

Washington, D.C.

[end of letter]

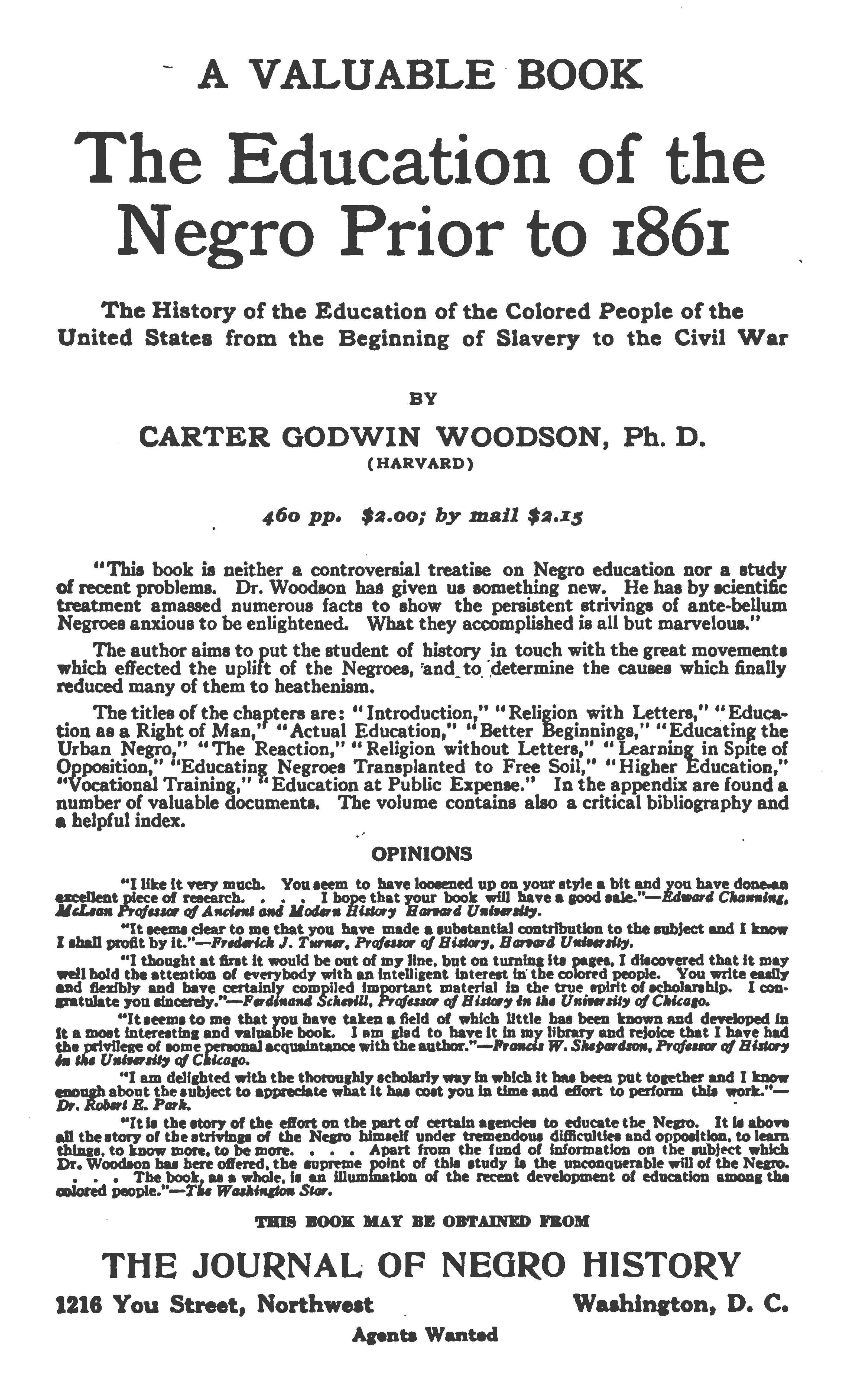

Immediately after completing his Ph.D., Woodson dedicated intense effort to expanding scholarship on Black history, revising his dissertation and developing new projects — such as his groundbreaking work The Education of the Negro Prior to 1861 (1919) — all while teaching full time. Carter G. Woodson to F. J. Turner. June 20, 1914/Courtesy of the Huntington Library, Art Collections and Botanical Gardens

Woodson had a cosmopolitan spirit. He spoke French and Spanish, and traveled to several countries on three continents, including France, where he studied at the Sorbonne in Paris. This worldview and love for languages led him to complete both a B.A. and M.A. degree in history at the University of Chicago.

Woodson then decided to further his graduate education in history and enrolled at Harvard University in 1908. Despite the casual racism he faced from faculty — many of whom believed, as his advisor Albert Bushnell Hart wrote in 1910, that “[r]ace measured by race, the Negro [was] inferior,” and consistently minimized the role of Black Americans in U.S. history — Woodson successfully completed his Ph.D. in 1912. His dissertation, “The Disruption of Virginia,” examines the causes for the separation of West Virginia from the state of Virginia during the Civil War, countering the popular belief that West Virginia broke away from the Confederacy due to opposition to slavery and instead identifying as the cause the economic and class differences between the “aristocracy” of the east and “dissenters” on the state’s Western frontier. When he graduated in 1912, Woodson became only the second Black person — W.E.B. Du Bois (A.B. 1890, A.M. 1891, Ph.D. 1895) had been the first — to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard University.

The Father of Black History

Just a few years after graduating from Harvard, he published The Education of the Negro Prior to 1861 (1919) and, after being banned from attending conferences of the almost exclusively white scholarly association the American Historical Association, founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life & History (ASNLH, now known as the Association for the Study of African American Life and History, or ASALH). While building a reputation as a leading scholar of Black history, he maintained his commitment to educating Black youth. He served as the principal of Armstrong Manual Training School in Washington, DC (1918), as well as Dean the School of Liberal Arts at Howard University (1919–1920) and West Virginia Collegiate Institute (1920–1922; now West Virginia State University) — both historically Black schools. He retired from teaching in 1922 to focus on the development of the ASNLH.

Determined to make Black history available to the masses, Woodson established Negro History Week in 1926.

All American News, Inc. All-American news, 1945-02, no. 2. Produced by William D. Alexander, E. M. Glucksman, and Claude Barnett. Feb. 25, 1945./Library of Congress, Motion Picture, Broadcasting, and Recorded Sound Division (Public Domain)

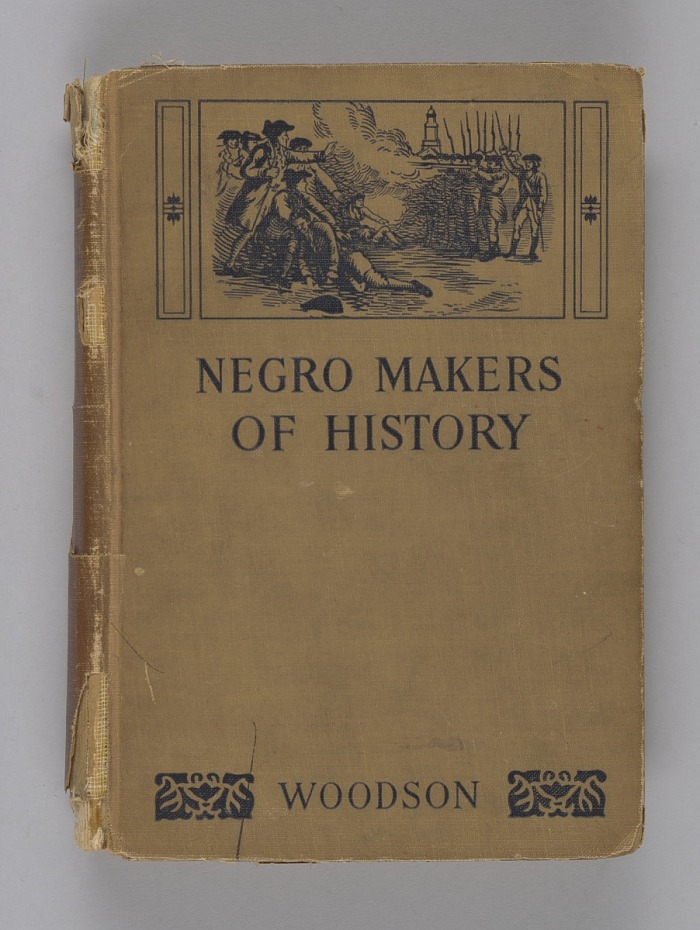

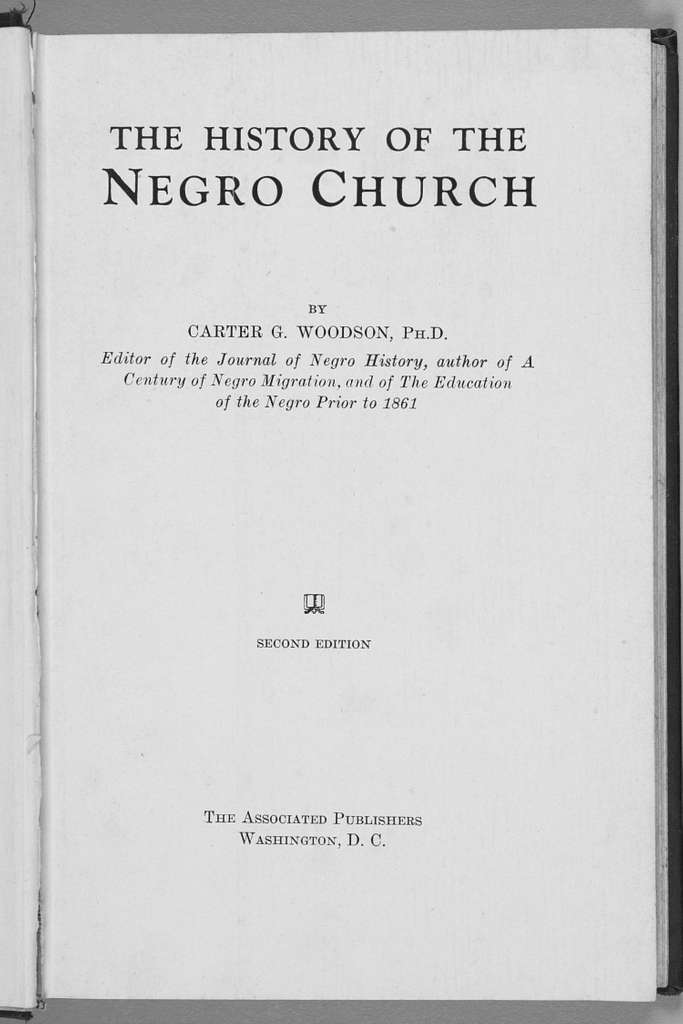

Alongside his essays and publications like “The History of the Negro Church” (1921), “Negro Makers of History” (1928), and “African Heroes and Heroines” (1939), he also created The Negro History Bulletin — still published today, as The Black History Bulletin — for educators and students to use in their history curricula. The popularity of Negro History Week eventually led to the establishment of the national Black History Month.

Carter G. Woodson. “Negro Makers of History”. Washington, DC. The Associated Publishers, Inc.. 1928/Public Domain

Carter G. Woodson. “The History of the Negro Church.” Washington, DC. The Associated Publishers, Inc.. 1921/Public Domain

Woodson founded The Journal of Negro History — now The Journal of African American History — in 1916. The Journal of Negro History vol. 1, no. 1. Carter G. Woodson, editor. The Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, Inc.. Washington, DC. 1916/Public Domain

Open and scroll to read the advertisement transcript

[double-line rectangular border surrounds the text]

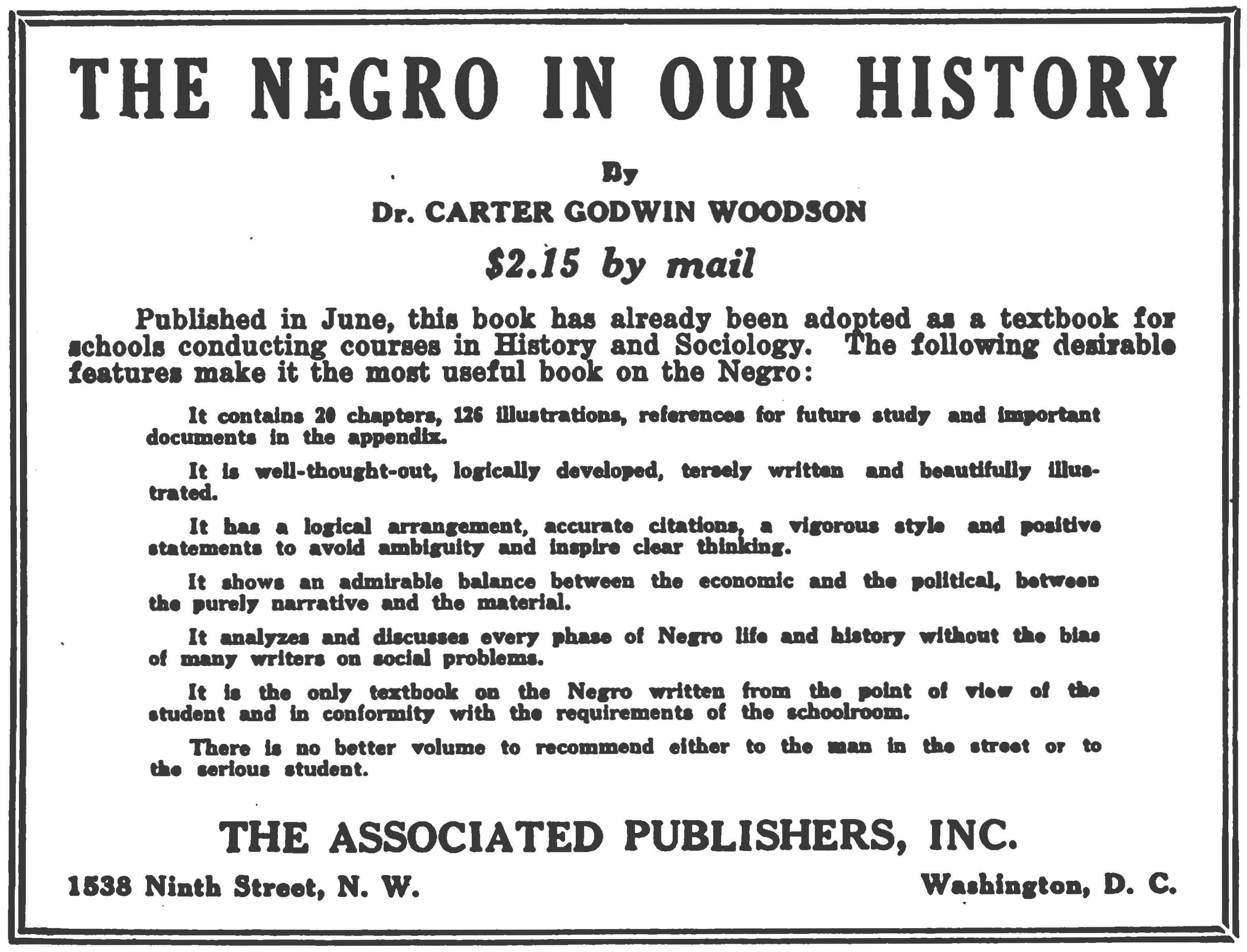

THE NEGRO IN OUR HISTORY

By

Dr. CARTER GODWIN WOODSON

$2.15 by mail

Published in June, this book has already been adopted as a textbook for schools conducting courses in History and Sociology. The following desirable features make it the most useful book on the Negro:

It contains 20 chapters, 126 illustrations, references for future study and important documents in the appendix.

It is well-thought-out, logically developed, tersely written and beautifully illustrated.

It has a logical arrangement, accurate citations, a vigorous style and positive states to avoid ambiguity and inspire clear thinking.

It shows an admirable balance between the economic and the political, between the purely narrative and the material.

It analyzes and discusses every phase of Negro life and history without the bias of many writers on social problems.

It is the only textbook on the Negro written from the point of view of the student and in conformity with the requirements of the schoolroom.

There is no better volume to recommend either to the man in the street or to the serious student.

THE ASSOCIATED PUBLISHERS, INC.

1538 Ninth Street, N. W. Washington, D. C.

[end of advertisement]

Woodson’s groundbreaking book “The Negro in Our History” (1922) remained a standard text in Black history for decades. Advertisement. The Crisis vol. 28, no. 1. May 1924/Public Domain

Open and scroll to read the advertisement transcript

A VALUABLE BOOK

The Education of the

Negro Prior to 1861

The History of the Education of the Colored People of the

United States from the Beginning of Slavery to the Civil War

BY

CARTER GODWIN WOODSON, Ph. D.

(Harvard)

460 pp. $2.00; by mail $2.15

“This book is neither a controversial treatise on Negro education nor a study of recent problems. Dr. Woodson has given us something new. He has by scientific treatment amassed numerous facts to show the persistent strivings of ante-bellum Negroes anxious to be enlightened. What they accomplished is all but marvelous.”

The author aims to put the student of history in touch with the great movements which effected the uplift of the Negroes, and to determine the causes which finally reduced many of them to heathenism.

The titles of the chapters are: “Introduction,” “Religion with Letters,” “Education as a Right of Man,” “Actual Education,” “Better Beginnings,” “Educating the Urban Negro,” “The Reaction,” “Religion without Letters,” Learning in Spite of Opposition,” “Educating Negroes Transplanted to Free Soil,” “Higher Education,” “Vocational Training,” “Education at Public Expense.” In the appendix are found a number of valuable documents. The volume contains also a critical bibliography and a helpful index.

OPINIONS

“I like it very much. You seem to have loosened up on your style a bit and you have done an excellent piece of research. … I hope that your book will have a good sale.” — Edward Channing, McLean Professor of Ancient and Modern History Harvard University.

“It seems clear to me that you have made a substantial contribution to the subject and I know I shall profit by it.” — Frederick J. Turner, Professor of History, Harvard University.

“I thought at first it would be out of my line, but on turning its pages, I discovered that it may well hold the attention of everybody with an intelligent interest in the colored people. You write easily and flexibly and have certainly compiled important material in the true spirit of scholarship. I congratulate you sincerely.” — Ferdinand Scherill, Professor of History in the University of Chicago.

“It seems to me that you have taken a field of which little has been known and developed in it a most interesting and valuable book. I am glad to have it in my library and rejoice that I have had the privilege of some personal acquaintance with the author.” — Francis W. Shepardson, Professor of History in the University of Chicago.

“I am delighted with the thoroughly scholarly way in which it has been put together and I know enough about the subject to appreciate what it has cost you in time and effort to perform this work.” — Dr. Robert E. Park.

“It is the story of the effort on the part of certain agencies to educate the Negro. It is above all the story of the strivings of the Negro himself under tremendous difficulties and opposition, to learn things, to know more, to be more. … Apart from the fund of information on the subject which Dr. Woodson has here offered, the supreme point of the study is the unconquerable will of the Negro. … The book, as a whole, is an illumination of the recent development of education among the colored people.” — The Washington Star.

THIS BOOK MAY BE OBTAINED FROM

THE JOURNAL OF NEGRO HISTORY

1216 You Street, Northwest Washington, D. C.

Agents Wanted

[end of advertisement]

Of “The Education of the Negro Prior to 1861” (1919), Professor Frederick Jackson Turner — one of Woodson’s supporters on the Harvard faculty — wrote, “It seems clear to me that you have made a substantial contribution to the subject and I know I shall profit by it.” Advertisement. Journal of Negro History vol. 1, no. 1. 1920/Public Domain

Open and scroll to read the article transcript

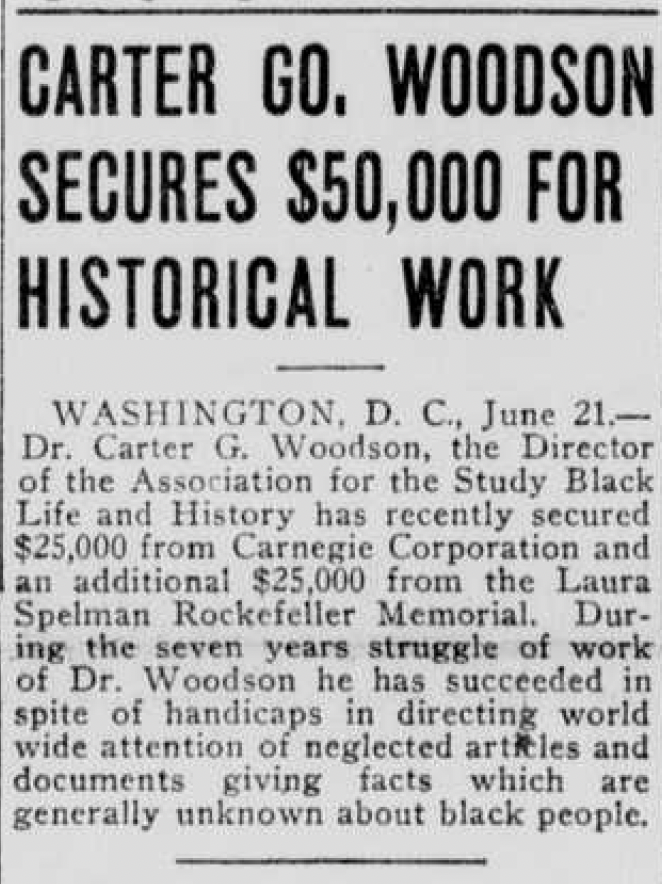

CARTER GO. WOODSON SECURES $50,000 FOR HISTORICAL WORK

WASHINGTON, D. C., June 21. — Dr. Carter G. Woodson, the Director of the Association for the Study Black Life and History has recently secured $25,000 from Carnegie Corporation and an additional $25,000 from the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial. During the seven years struggle of work of Dr. Woodson he has succeeded in spite of handicaps in directing world wide attention of neglected articles and documents giving facts which are generally unknown about black people.

[end of article]

Woodson was tireless in his efforts to illuminate Black history. One 1922 article noted that he “has succeeded in spite of handicaps in directly worldwide attention [to…] facts which are generally unknown about black people.” “Carter Go. Woodson Secures $50,000 for Historical Work.” The Chicago Whip. June 24, 1922/Public Domain

Memorial Legacy

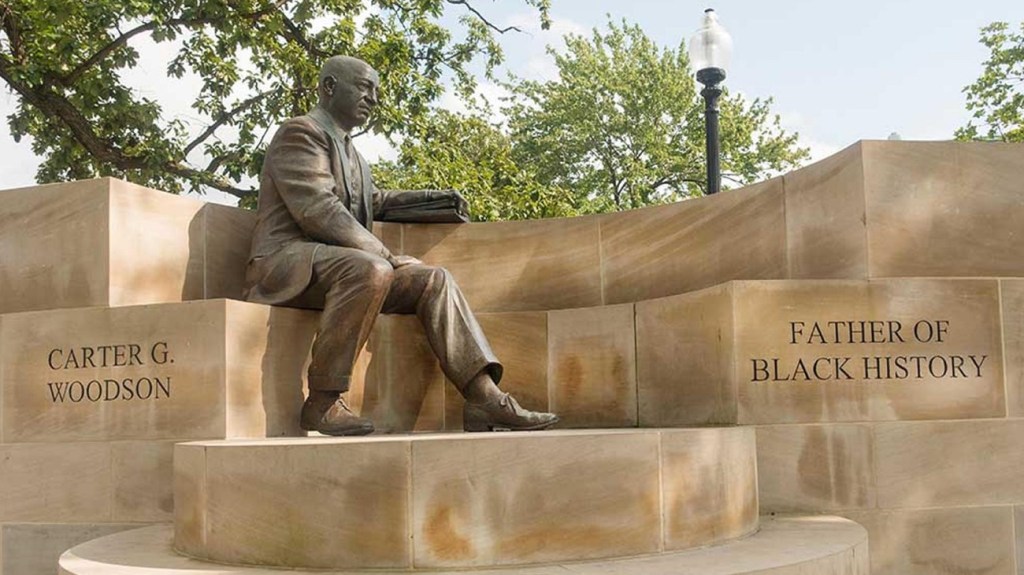

After Woodson’s death in 1950, he was widely lauded for his groundbreaking work in the field of Black history in the United States. In addition to a U.S. postage stamp issued in February 1984, memorials honoring Woodson’s legacy include the Carter G. Woodson Institute at the University of Virginia, founded in 1981; the Carter G. Woodson Memorial Park in Washington DC, established by Congress in December 2003; and a host of other parks, memorials, and national historic sites in New York, West Virginia, and Florida.

More than a century after he founded the Association for the Study of African American Life and History, the organization and its members continue the work Woodson began, to “promote, research, preserve, interpret and disseminate information about Black life, history and culture to the global community.”

Selected Sources

“Carter G. Woodson.” NAACP. Accessed August 10, 2023.

Goggin, Jacqueline Anne. Carter G. Woodson: A Life in Black History. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1993.

Givens, Jarvis R. Fugitive Pedagogy: Carter G. Woodson and the Art of Black Teaching. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2021.

Morris, Burnis R. “Carter G. Woodson: The Early Years, 1875–1903.” ASALH: The Association for the Study of African American Life and History. Accessed September 13, 2023.

Stevenson, Brenda E. “‘Out of the Mouths of Ex-Slaves’: Carter G. Woodson’s Journal of Negro History “Invents” the Study of Slavery.” The Journal of African American History 100, no. 4 (2015): 698–720.

More profiles

Charles Hamilton Houston

Known as “The Man Who Killed Jim Crow,” Charles Hamilton Houston was the first Black person to both serve on the Harvard Law Review and earn a Doctor of Juridical Science (S.J.D.) from Harvard Law…

Ewart Guinier

Ewart G. Guinier was the founding chair of Harvard’s first Department of Afro-American Studies in 1969—a bittersweet return to Harvard decades after he faced a dispiriting student experience from 1929 to 1931. Guinier devoted his…

Richard T. Greener

Harvard College’s first Black graduate, Richard T. Greener went on to become the first Black professor at the University of South Carolina and dean of the Howard University School of Law.