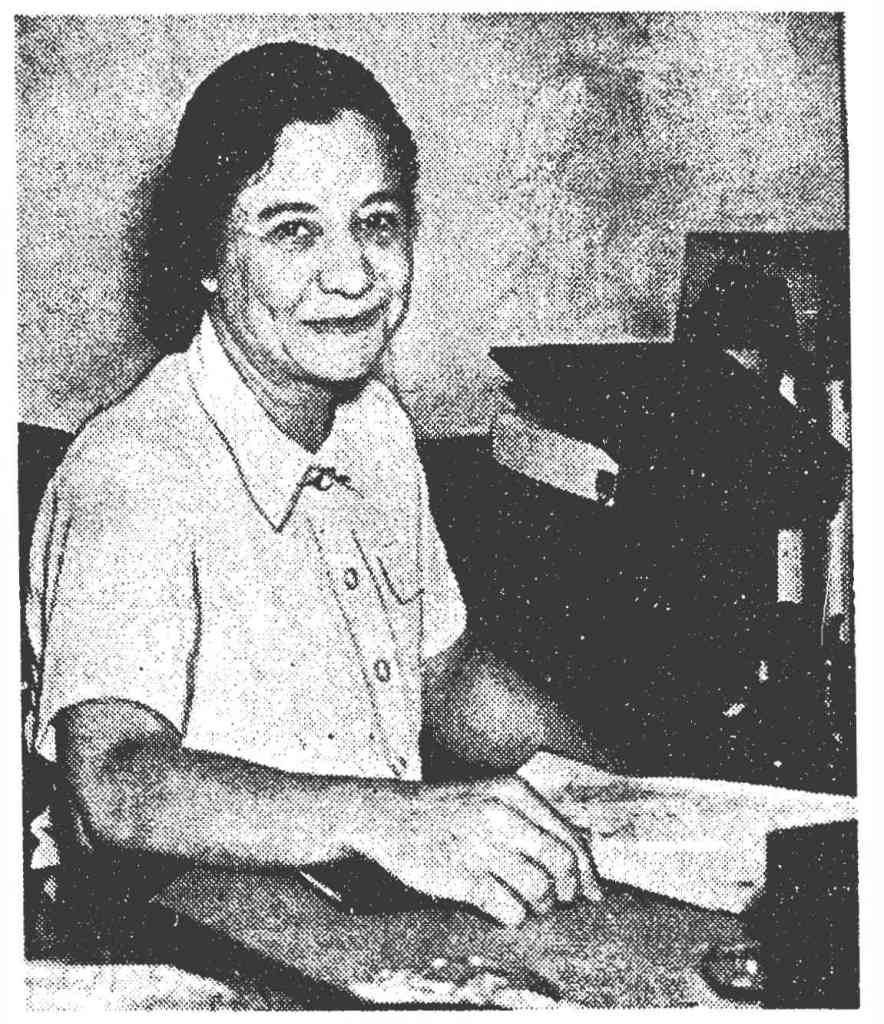

Caroline Bond Day

Class of 1930

Caroline Bond Day

Caroline Bond Day earned her A.M. in anthropology in 1930, making her one of the first Black people to earn a graduate degree from Radcliffe College. Her work in anthropology directly challenged the racial hierarchies advanced by eugenicists whose racist ideas dominated the field during her career.

School: Radcliffe College

Degree: A.B., A.M.

Area of Impact: Education, Anthropology, Social Work

HBCU Affiliation: Clark Atlanta University, Howard University, North Carolina Central University, Prairie View A&M

Early Life — and Two College Degrees

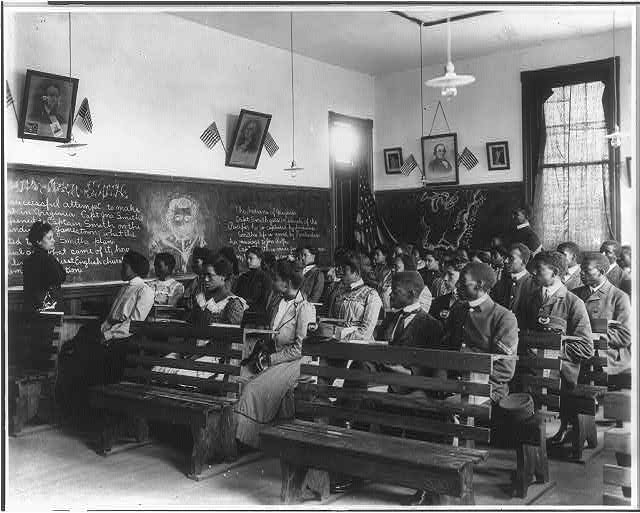

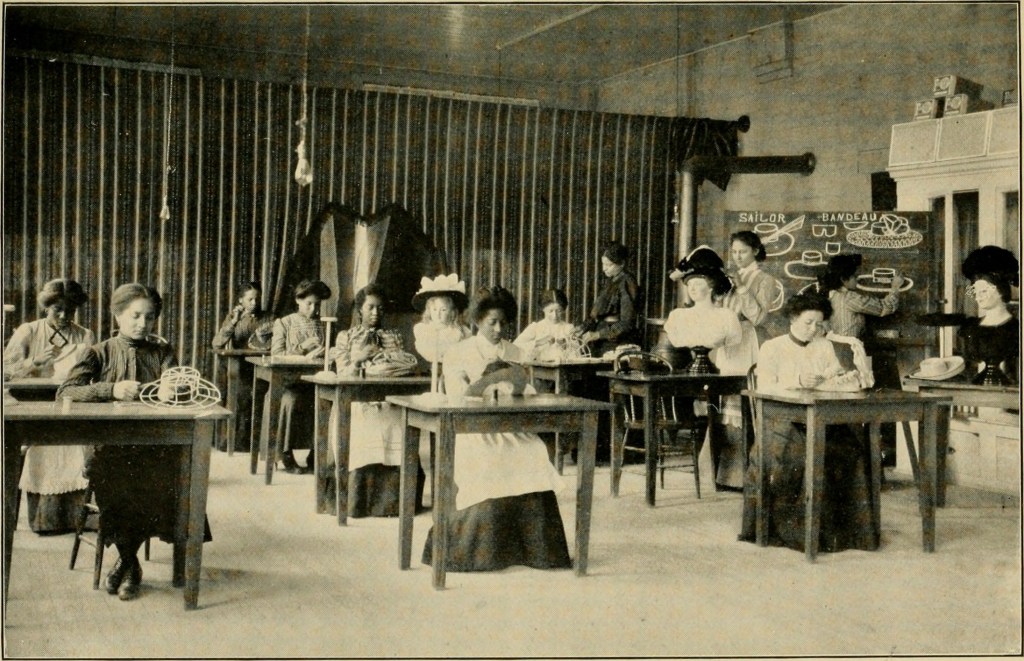

Caroline Bond Day was born in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1889. After her father’s death, Day’s mother — who had attended Fisk University prior to her marriage and was determined her daughter would receive a good education — moved them to Boston, where Day spent several formative years. During this time her mother served as a weekend guardian for the teenaged son of Tuskegee Institute (now Tuskegee University) principal Booker T. Washington. This connection led her to uproot again in 1902, moving with her daughter to Alabama where she taught laundering courses at the Tuskegee Institute in order to allow Day to attend the school.

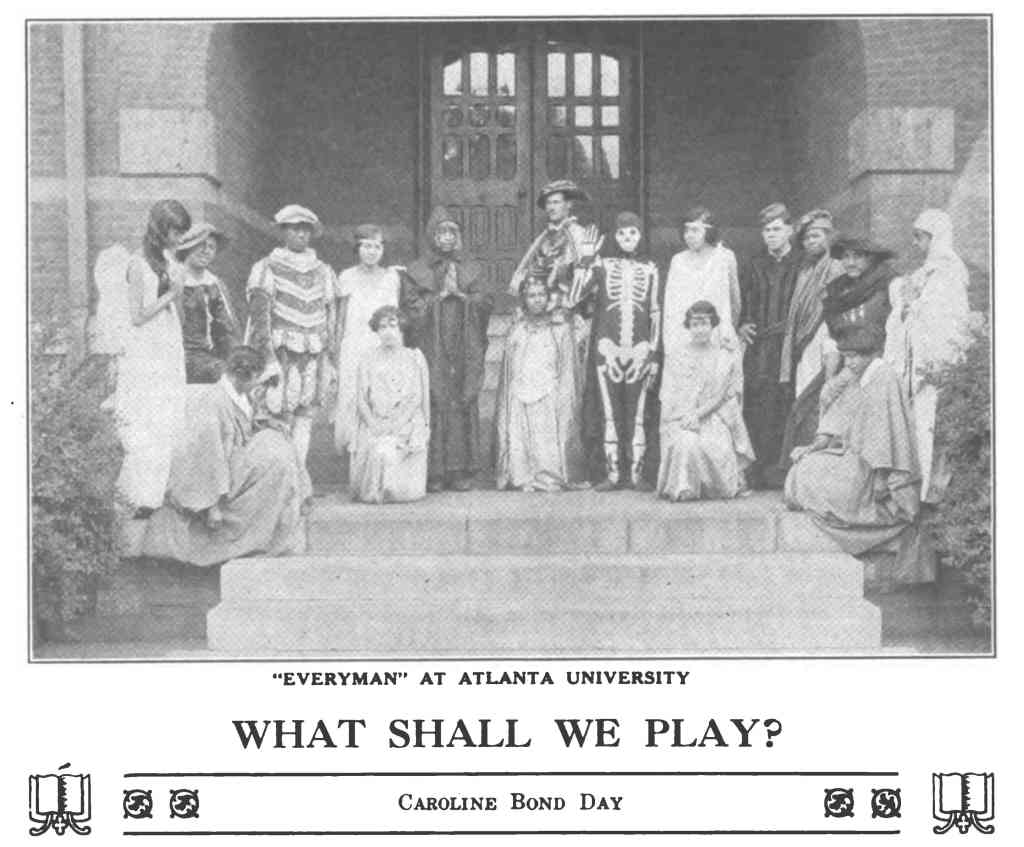

Day flourished in her three years at Tuskegee and, despite struggling with a chronic illness, went on to earn her first bachelor’s degree in 1912 at Atlanta University (today Clark Atlanta University). There she was mentored by Adrienne Herndon, the director of dramatics, and by Harvard alumnus, W.E.B. Du Bois (A.B. 1890, A.M. 1891, Ph.D. 1895), who encouraged her to pursue anthropology at Radcliffe. After graduation she spent a year teaching at the Normal School for Colored Students (now Alabama State University), followed by three years as director of the Montclair, New Jersey, Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) “For Colored Women.”

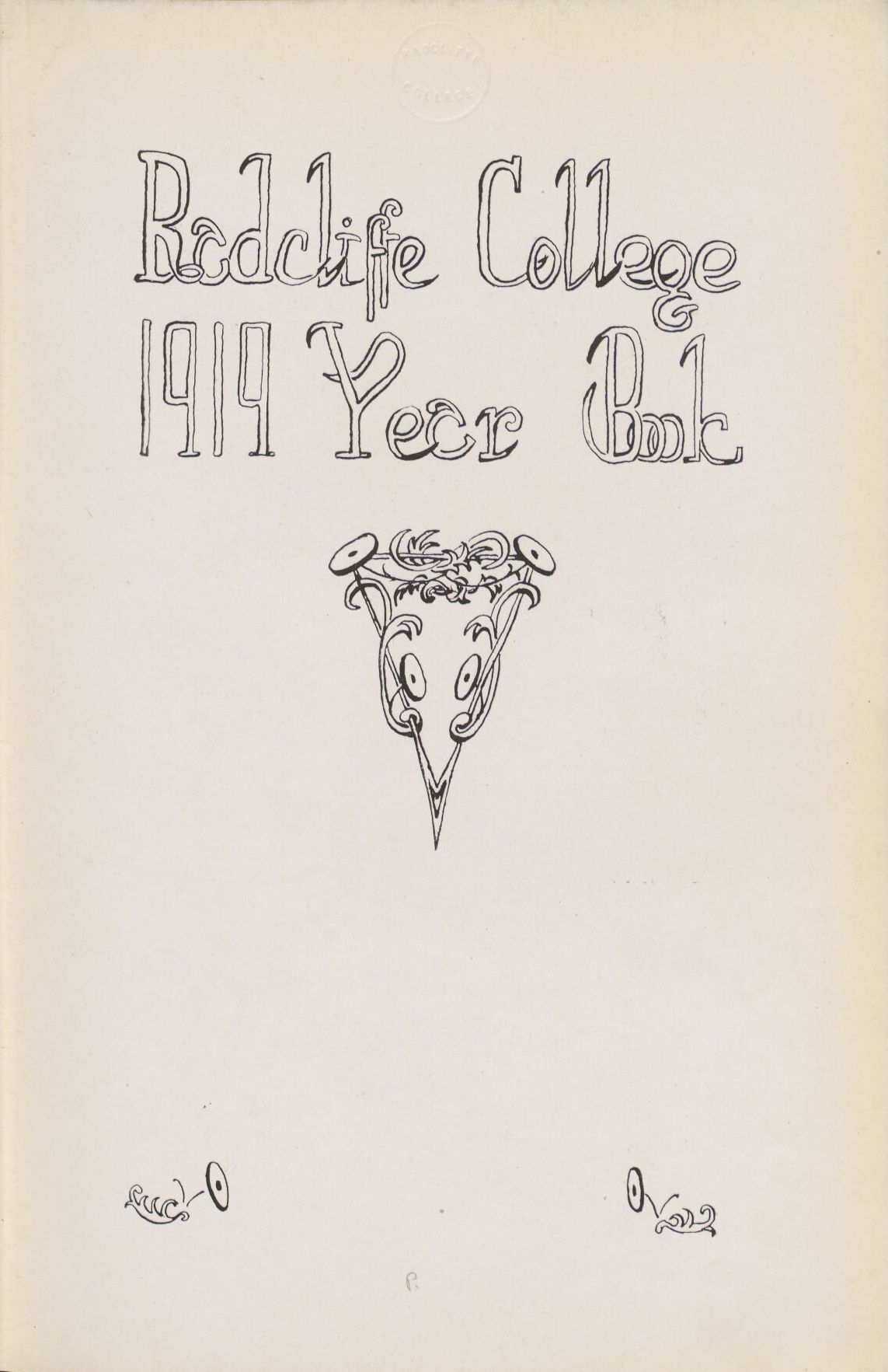

When she finally entered Radcliffe in 1916, the College would not recognize her degree from Atlanta University because, like many other Black institutions in this era, it was denied accreditation by the Southern Association of Colleges. She enrolled as an undergraduate; her profile in the 1919 Year Book noted that she “[t]ransferred from Atlanta University.” Despite her interest in anthropology — a field populated almost exclusively by men — she focused on her other passion, majoring in English and Classical Literature. Denied housing on campus in the 1916–1917 academic year, she commuted from lodgings five miles away in Boston’s South End.

After the United States entered World War I in 1917, Day stepped away from her studies for a year to work for the Circle for Negro War Relief in New York City.

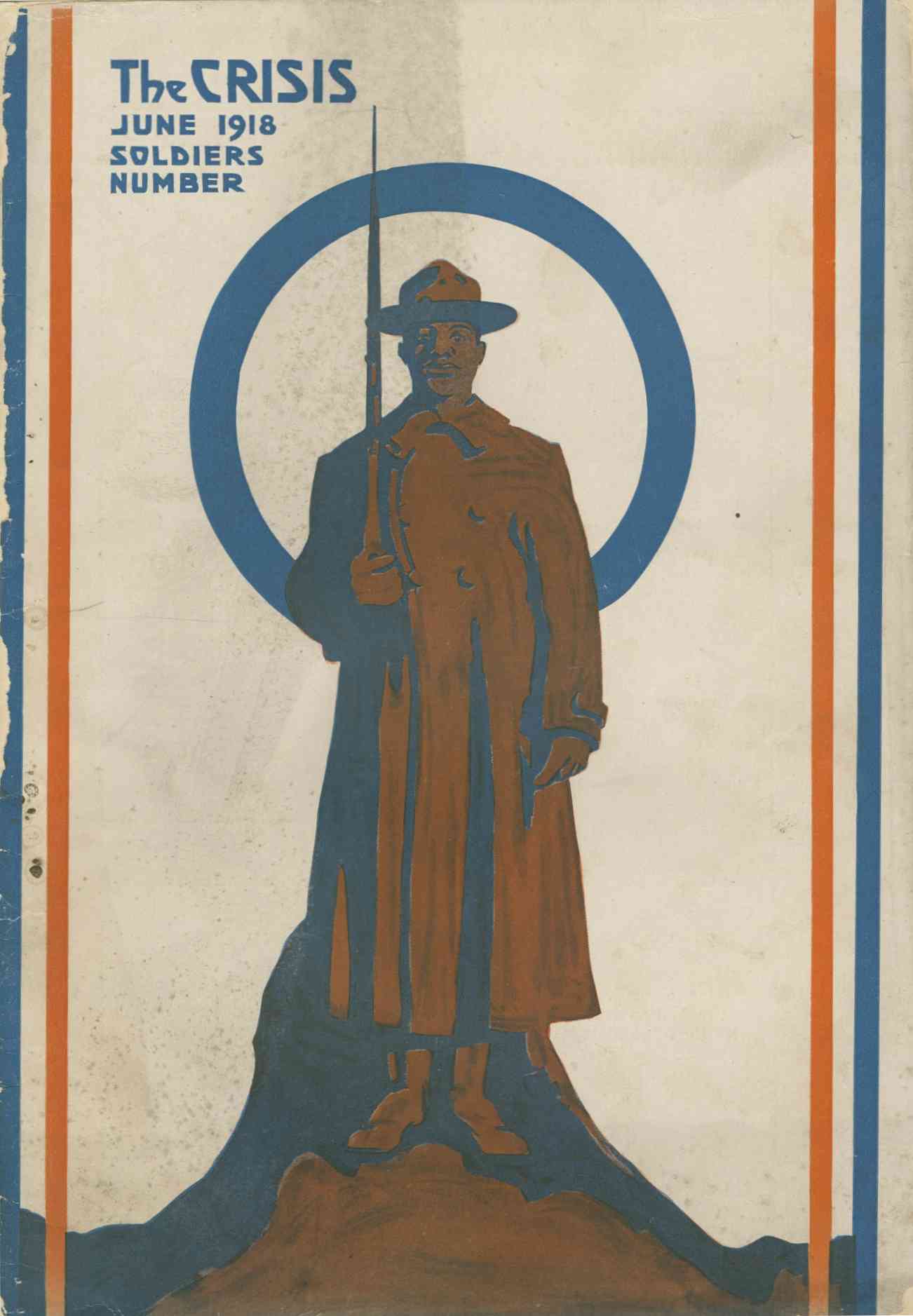

After the United States entered World War I, Day left Radcliffe for the 1917–1918 academic year to serve as executive secretary of the Circle for Negro War Relief. Robert Edmond Jones, illustrator. “Soldiers Number.” The Crisis 16, no. 2. New York, NY: National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, June 1918/Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of Bobbie Ross in memory of Elizabeth Dillard (Public Domain)

Open and scroll to read the page transcript

[page header] THE CRISIS ADVERTISER

[decorative patterned line border surrounds the remainder of the text on the page]

The Circle for Negro War Relief, Inc.

[horizontal line divider]

MRS. EMILIE BIGELOW HAPGOOD, President

VICE PRESIDENTS

Governor Charles S. Whitman Dr. W.E. Burghardt Du Bois

Dr. Robert R. Moton Colonel Charles Young Ray Stannard Baker

HARRISON RHODES, Treasurer MRS. JAMES W. JOHNSON, Secretary

CAROLINE S. BOND, Executive Secretary

DIRECTORS [presented in three columns]

Governor Chas. S. Whitman

Dr. W.E. Burghardt Du Bois

Col. Charles Young

George Foster Peabody

Mrs. Amos R. E. Pinchot

Mrs. James W. Johnson

Ray Stannard Baker

Mrs. Emilie Bigelow Hapgood

Charles S. Peabody

A. B. Spingarn

Russell Janney

Dr. Robert R. Motor.

[presented in two columns]

Edward Sheldon

Robert J. Coady

[horizontal line divider]

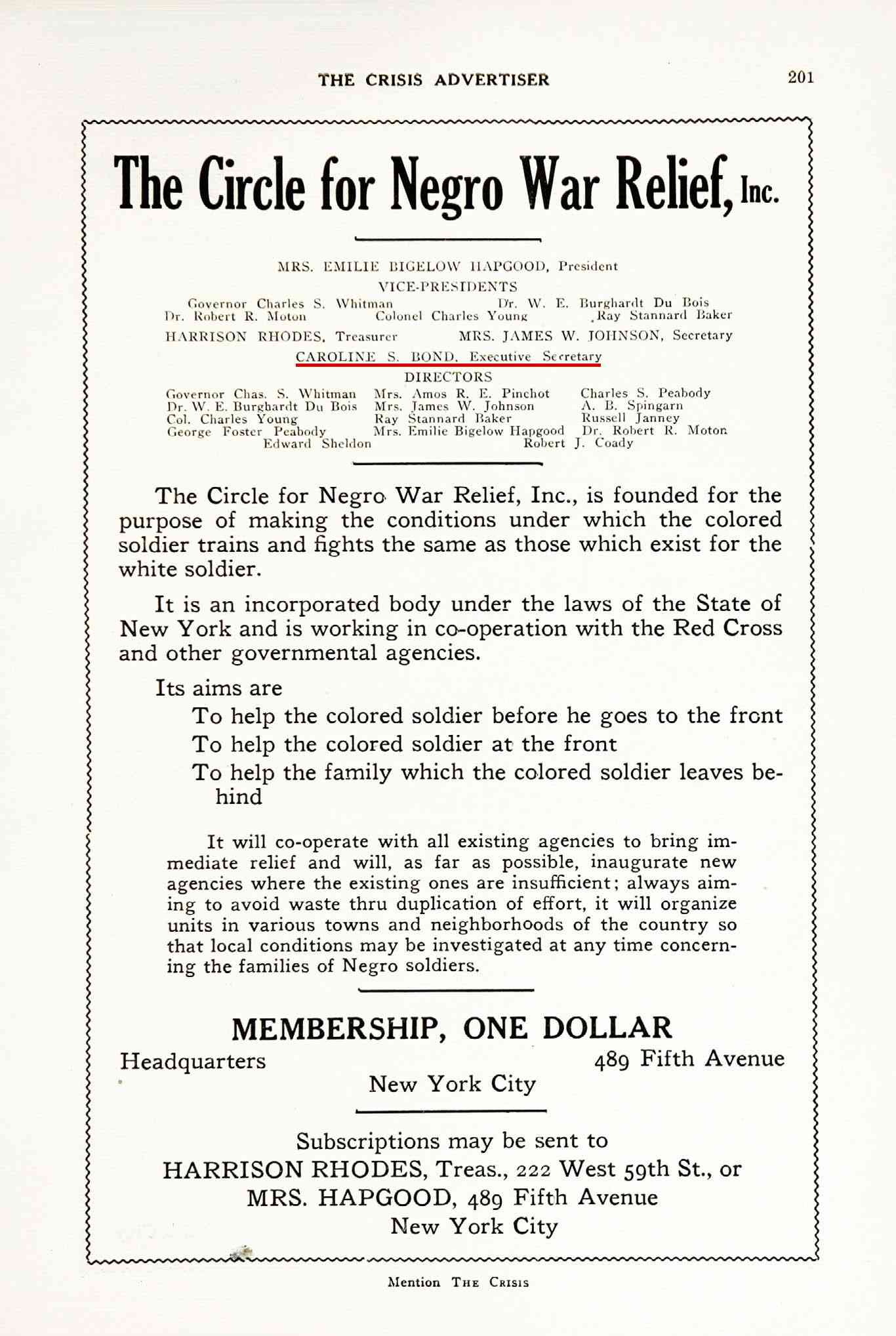

The Circle for Negro War Relief, Inc., is founded for the purpose of making the conditions under which the colored soldier trains and fights the same as those which exist for the white soldier.

It is an incorporated body under the laws of the State of New York and is working in co-operation with the Red Cross and other governmental agencies.

Its aims are

To help the colored soldier before he goes to the front

To help the colored soldier at the front

To help the family which the colored soldier leaves behind

It will co-operate with all existing agencies to bring immediate relief and will, as far as possible, inaugurate new agencies where the existing ones are insufficient; always aiming to avoid waste thru duplication of effort, it will organize units in various towns and neighborhoods of the country so that local conditions may be investigated at any time concerning the families of Negro soldiers.

[horizontal line divider]

MEMBERSHIP, ONE DOLLAR

Headquarters 489 Fifth Avenue

New York City

[horizontal line divider]

Subscriptions may be sent to HARRISON RHODES, Treas., 222 West 59th St., or

MRS. HAPGOOD, 489 Fifth Avenue

New York City

[below bottom border] Mention The Crisis

[end of advertisement]

The Circle for Negro War Relief was expressly “founded for the purpose of making the conditions under which the colored soldier trains and fights the same as those which exist for the white soldier.” Circle for Negro War Relief advertisement. The Crisis 15, no. 4. February 1918/Public Domain

Open and scroll to read the page transcript

[page header] THE CRISIS ADVERTISER

[line border surrounds the remainder of the text on the page]

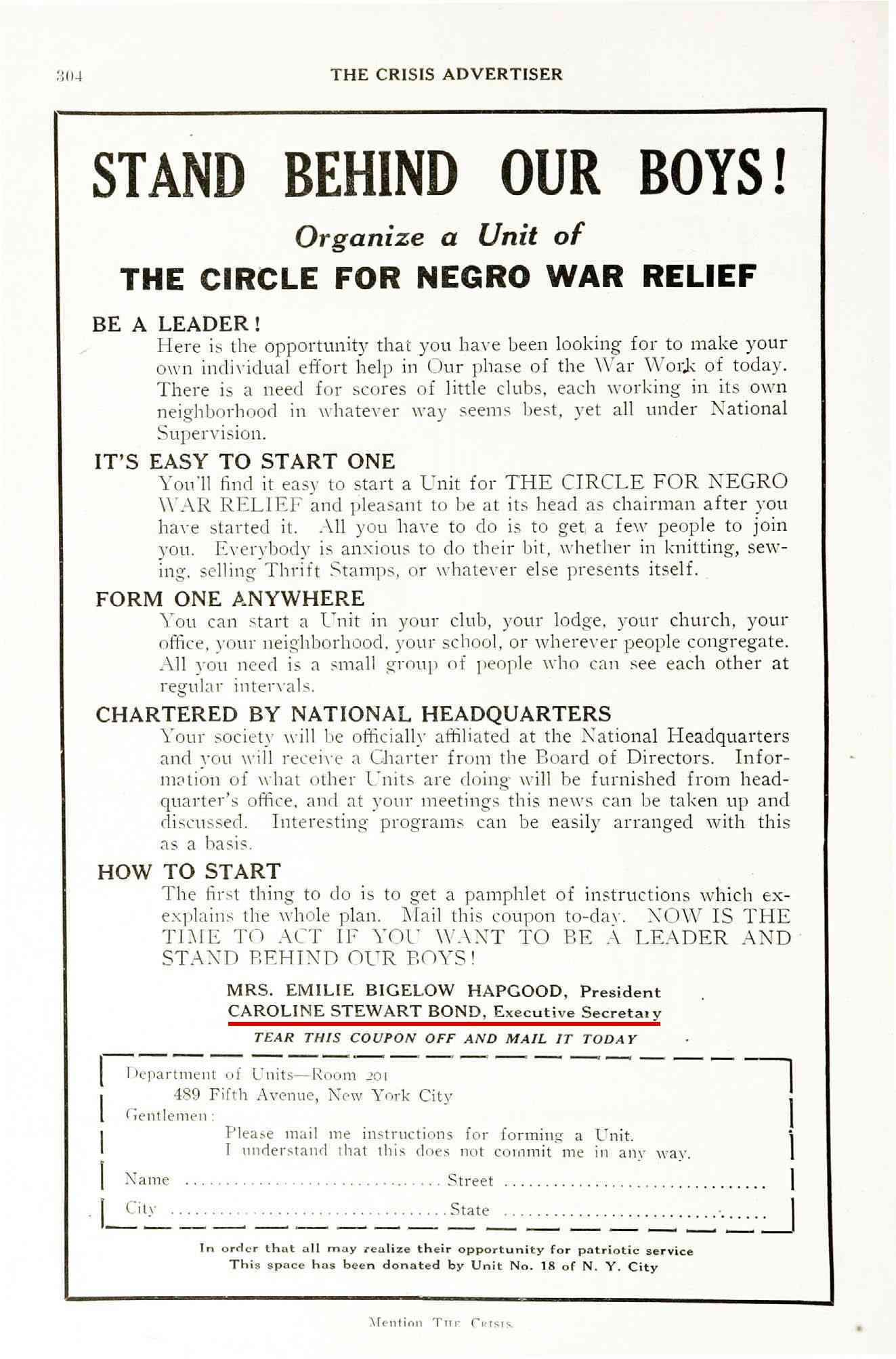

STAND BEHIND OUR BOYS!

Organize a Unit of

THE CIRCLE FOR NEGRO WAR RELIEF

BE A LEADER !

Here is the opportunity that you have been looking for to make your own individual effort help in Our phase of the War Work of today. There is a need for scores of little clubs, each working in its own neighborhood in whatever way seems best, yet all under National Supervision.

IT’S EASY TO START ONE

You’ll find it easy to start a Unit for THE CIRCLE FOR NEGRO WAR RELIEF and pleasant to be at its head as chairman after your have started it. All you have to do is to get a few people to join you. Everybody is anxious to do their bit, whether in knitting, sewing, selling Thrift Stamps, or whatever else presents itself.

FORM ONE ANYWHERE

You can start a Unit in your club, your lodge, your church, your office, your neighborhood, your school, or wherever people congregate. All you need is a small group of people who can see each other at regular intervals.

CHARTERED BY NATIONAL HEADQUARTERS

Your society will be officially affiliated at the National Headquarters and you will receive a Charter from the Board of Directors. Information of what other Units are doing will be furnished from headquarter’s office, and at your meetings this news can be taken up and discussed. Interesting programs can be easily arranged with this as a basis.

HOW TO START

The first thing to do is to get a pamphlet of instructions which ex- explains the whole plan. Mail this coupon to-day. NOW IS THE TIME TO ACT IF YOU WANT TO BE A LEADER AND STAND BEHIND OUR BOYS!

MRS. EMILIE BIGELOW HAPGOOD, President

[red underline inserted by website designers] CAROLINE STEWART BOND, Executive Secretary

TEAR THIS COUPON OFF AND MAIL IT TODAY

[dashed line forming a rectangular border around the following text]

Department of Units — Room 201

489 Fifth Avenue, New York City

Gentlemen:

Please mail me instructions for forming a Unit.

I understand that this does not commit me in any way.

Name …………………………Street…………………………

City …………………………State …………………………

[bottom of dashed rectangular border]

In order that all may realize their opportunity for patriotic service

This space has been donated by Unit No. 18 of N. Y. City

[below bottom border] Mention The Crisis

[end of advertisement]

The organization was made up of local units across the country — The Crisis reported in June 1918 that there were 50 units in 25 states — that fundraised to support Black soldiers in training and at the front, as well as the families they left behind. Circle for Negro War Relief advertisement. The Crisis vol. 15, no. 6. April 1918/Public Domain

Open and scroll to read the page transcript

BULLETIN OF

CIRCLE FOR NEGRO WAR RELIEF

(INCORPORATED)

[double horizontal dividing line]

JULY 1, 1918

[double horizontal dividing line]

[printed circle with one thin inner ring surrounded by a thicker outer ring]

[printed in two columns]

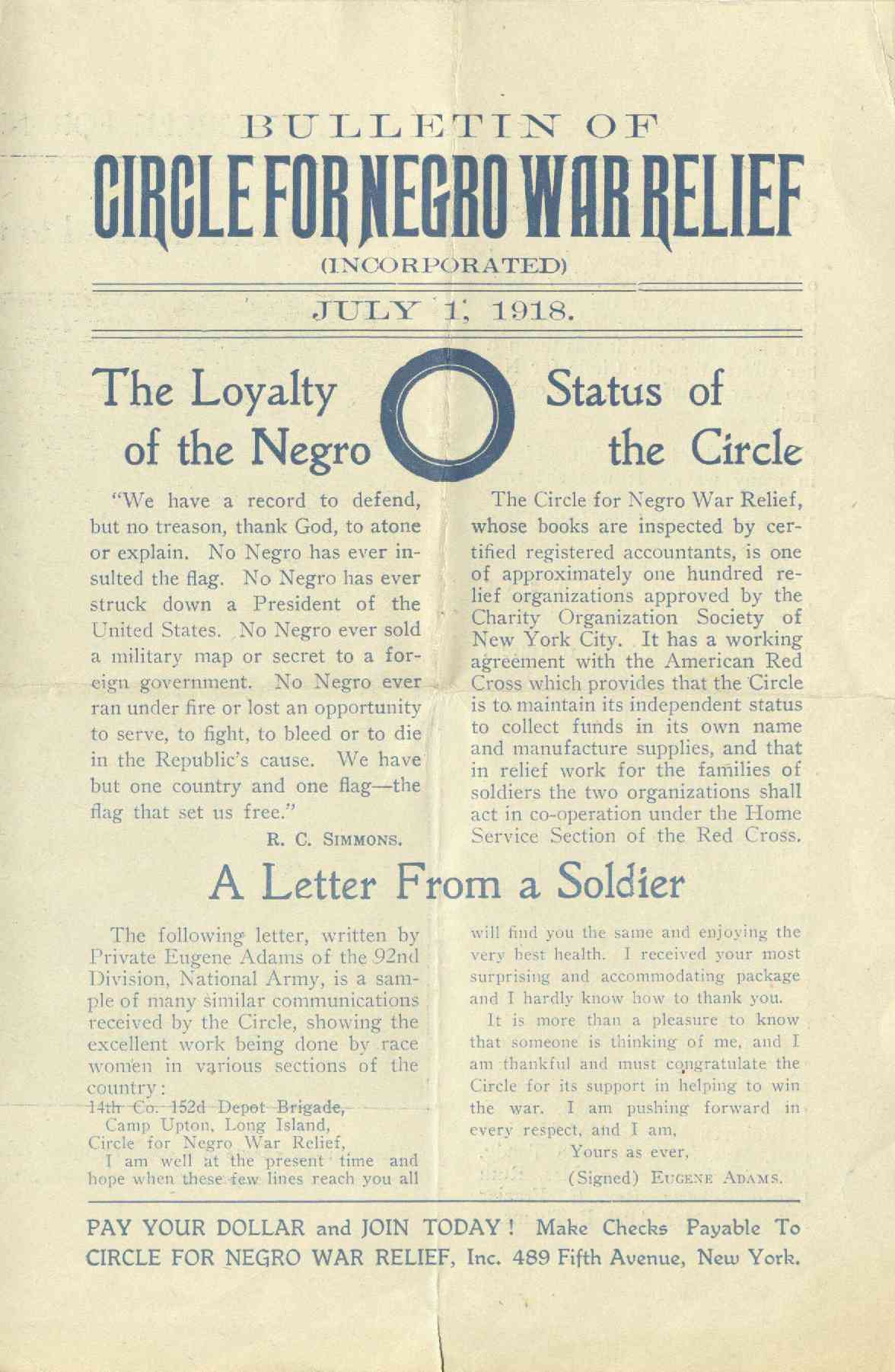

The Loyalty of the Negro

“We have a record to defend, but not reason, thank God, to atone or explain. No Negro has ever insulted the flag. No Negro has ever struck down a President of the United States. No Negro ever sold a military map or secret to a foreign government. No Negro ever ran under fire or lost an opportunity to serve, to fight, to bleed or to die in the Republic’s cause. We have but one country and one flag — the flag that set us free.”

R. C. SIMMONS.

Status of the Circle

The Circle for Negro War Relief, whose books are inspected by certified registered accountants, is one of approximately one hundred relief organizations approved by the Charity Organization Society of New York City. It has a working agreement with the American Red Cross which provides that the Circle is to maintain its independent status to collect funds in its own name and manufacture supplies, and that in relief work for the families of soldiers the two organizations shall act in co-operations under the Home Service Section of the Red Cross.

[centered on page]

A Letter From a Soldier

[two columns]

The following letter, written by Private Eugene Adams of the 92nd Division, National Army, is a sample of many similar communications received by the Circle, showing the excellent work being done by race women in various sections of the country:

14th Co. 152d Depot Brigade,

Camp Upton, Long Island,

Circle for Negro War Relief,

I am well at the present time and hope when these few lines reach you all will find you the same and enjoying the very best health. I received your most surprising and accommodating package and I hardly know how to thank you.

It is more than a pleasure to know that someone is thinking of me, and I am thankful and must congratulate the Circle for its support in helping to win the war. I am pushing forward in every respect, and I am,

Yours as ever,

(Signed) EUGENE ADAMS.

[horizontal dividing line]

[single column]

PAY YOUR DOLLAR and JOIN TODAY! Make Checks Payable To

CIRCLE FOR NEGRO WAR RELIEF, Inc. 489 Fifth Avenue, New York.

[end of page]

The organization had a working agreement with the American Red Cross that allowed it to raise funds to manufacture supplies and provide other supports to Black American soldiers and their families. Bulletin of Circle for Negro War Relief Incorporated. July 1, 1918/Neighborhood Union Collection, Atlanta University Center Robert W. Woodruff Library

Open and scroll to read the page transcript

THE CIRCLE FOR NEGRO WAR RELIEF

[double horizontal dividing line]

[column 1]

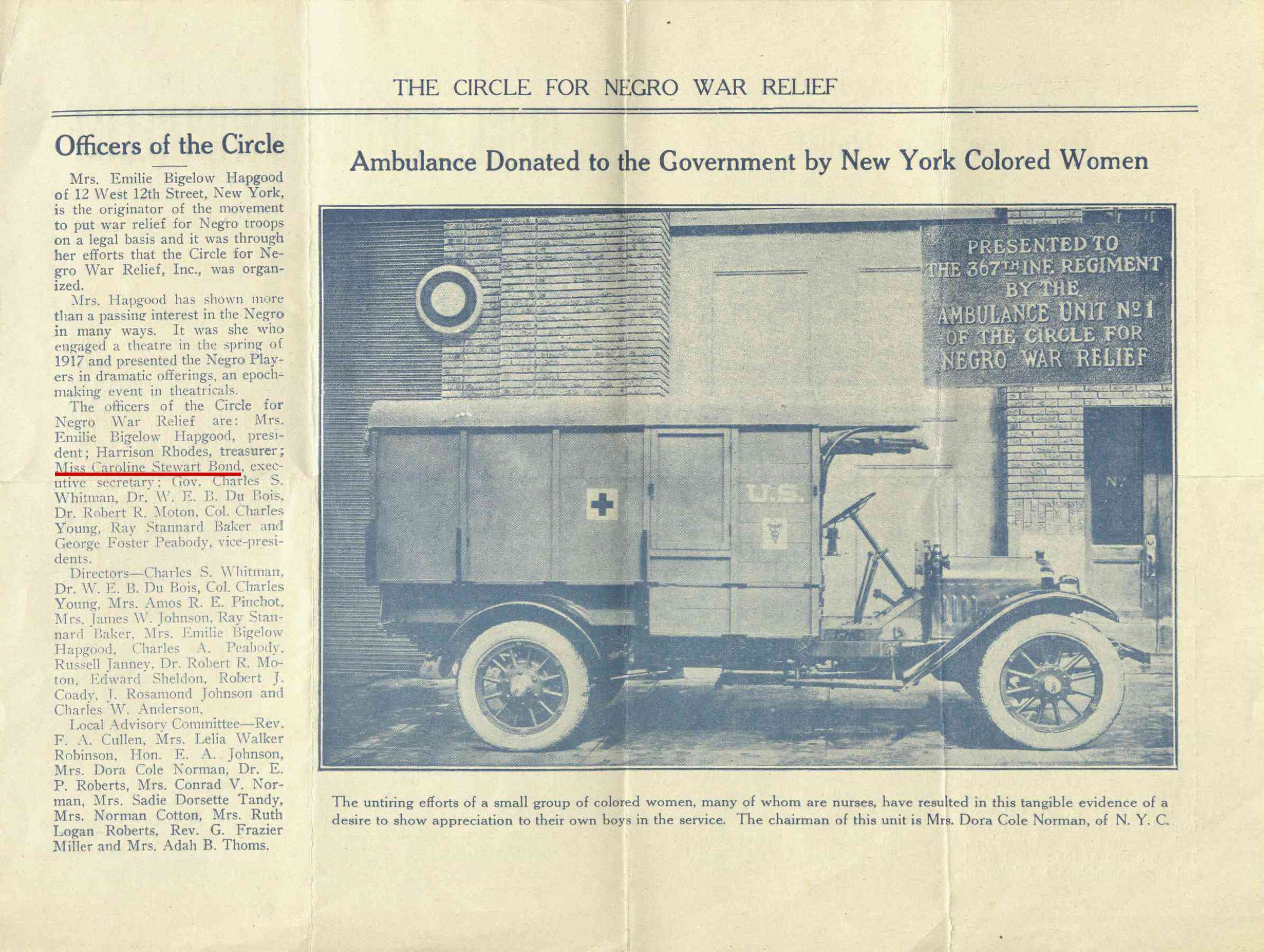

Officers of the Circle

Mrs. Emilie Bigelow Hapgood of 12 West 12th Street, New York, is the originator of the movement to put war relief for Negro troops on a legal basis and it was through her efforts that the Circle for Negro War Relief, Inc., was organized.

Mrs. Hapgood has shown more than a passing interest in the Negro in many ways. It was she who engaged a theatre in the spring of 1917 and presented the Negro Players in dramatic offerings, an epoch-making event in theatricals.

The officers of the Circle for Negro War Relief are: Mrs. Emily Bigelow Hapgood, president; Harrison Rhodes, treasurer; [name underlined in red by web designer] Miss Caroline Stewart Bond, executive secretary; Gov. Charles S. Whitman, Dr. W.E.B. Du Bois, Dr. Robert R. Moton, Col. Charles Young, Ray Stannard Baker and George Foster Peabody, vice-presidents.

Directors — Charles S. Whitman, Dr. W.E.B. Du Bois, Col. Charles Young, Mrs. Amos R. E. Pinchot, Mrs. James W. Johnson, Ray Stannard Baker, Mrs. Emilie Bigelow Hapgood, Charles A. Peabody, Russell Janney, Dr. Robert R. Moton, Edward Sheldon, Robert J. Coady, J. Rosamond Johnson and Charles W. Anderson.

Local Advisory Committee — Rev. F. A. Cullen, Mrs. Lelia Walker Robinson, Hon. E. A. Johnson, Mrs. Dora Cole Norman, Dr. E. P. Roberts, Mrs. Conrad V. Norman, Mrs. Sadie Dorsette Tandy, Mrs. Norman Cotton, Mrs. Ruth Logan Roberts, Rev. G. Frazier Miller and Mrs. Adah B. Thoms.

[displayed across columns 2–4]

Ambulance Donated to the Government by New York Colored Women

[black and white photograph taken from the side of what appears to be a Ford Model T ambulance with the Red Cross symbol and the letters “U. S.” painted on the side; text in the top right corner of the image reads, “PRESENTED TO THE 367TH INF. REGIMENT BY THEAMBULANCE UNIT NO 1 OF THE CIRCLE FOR NEGRO WAR RELIEF”]

The untiring efforts of a small group of colored women, many of whom are nurses, have resulted in this tangible evidence of a desire to show appreciation to their own boys in the service. The chairman of this unit is Mrs. Dora Cole Norman, of N. Y. C.

[end of page]

Caroline Bond Day served as executive secretary of the national organization, where her mentor W.E.B. Du Bois served on the integrated leadership team as both a vice president and director. Bulletin of Circle for Negro War Relief Incorporated. July 1, 1918/Neighborhood Union Collection, Atlanta University Center Robert W. Woodruff Library

Open and scroll to read the page transcript

THE CIRCLE FOR NEGRO WAR RELIEF

[double horizontal dividing line]

[centered on page]

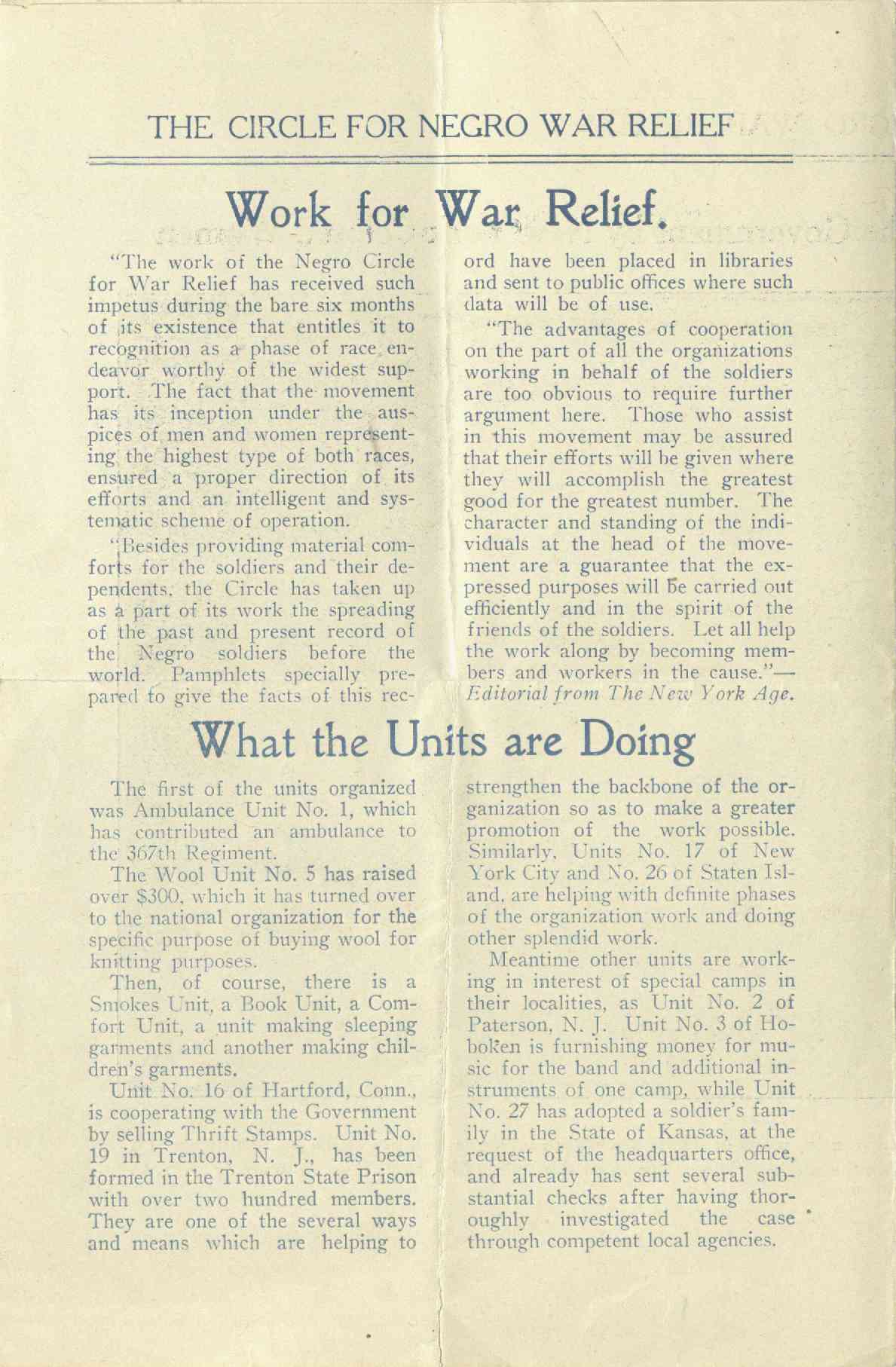

Work for War Relief.

[two columns]

“The work of the Negro Circle for War Relief has received such impetus during the bare six months of its existence that entitles it to recognition as a phase of race endeavor worthy of the widest support. The fact that the movement has its inception under the auspices of men and women representing the highest type of both races, ensured a proper direction of its efforts and an intelligent and systematic scheme of operation.

“Besides providing material comforts for the soldiers and their dependents, the Circle has taken up as a part of its work the spreading of the past and present record of the Negro soldiers before the world. Pamphlets specially prepared to give the facts of this record have been placed in libraries and sent to public offices where such data will be of use.

“The advantages of cooperation on the part of all the organizations working in behalf of the soldiers are too obvious to require further argument here. Those who assist in this movement may be assured that their efforts will be given where they will accomplish the greatest good for the greatest number. The character and standing of the individuals at the head of the movement are a guarantee that the expressed purposes will be carried out efficiently and in the spirit of the friends of all the soldiers. Let all help the work along by becoming members and works in the cause.” — Editorial from The New York Age.

[centered on page]

What the Units are Doing

[two columns]

The first of the units organized was Ambulance Unit No. 1, which has contributed an ambulance to the 367th Regiment.

The Wool Unit No. 5 has raised over $300, which it has turned over to the national organization for the specific purpose of buying wool for knitting purposes.

Then, of course, there is a Smokes Unit, a Book Unit, a Comfort Unit, a unit making sleeping garments, and another making children’s garments.

Unit No. 16 of Hartford, Conn., is cooperating with the Government by selling Thrift Stamps. Unit No. 19 in Trenton, N. J., has been formed in the Trenton State Prison with over two hundred members. They are one of the several ways and means which are helping to strengthen the backbone of the organization so as to make a greater promotion of the work possible. Similarly, Units No. 17 of New York City and No. 26 of Staten Island, are helping with definite phases of the organization work and doing other splendid work.

Meantime other units are working in interest of special camps in their localities, as Unit No. 2 of Paterson, N. J. Unit No. 3 of Hoboken is furnishing money for music for the band and additional instruments of one camp, while Unit No. 27 has adopted a soldier’s family in the State of Kansas, at the request of the headquarters office, and already has sent several substantial checks after having thoroughly investigated the case through competent local agencies.

[end of page; end of bulletin]

The organization’s work included knitting and making clothes for Black soldiers and their families, as well as buying equipment for segregated troops. One unit donated an ambulance to a Black regiment bound for France. Bulletin of Circle for Negro War Relief Incorporated. July 1, 1918/Neighborhood Union Collection, Atlanta University Center Robert W. Woodruff Library

She returned to Radcliffe in the fall of 1918, once again living several miles from campus in Boston’s South End neighborhood. She socialized with Black women enrolled at universities around the city, joining the chapter of the historically Black sorority Delta Sigma Theta organized that year by fellow English student Marita Bonner.

It was during her senior year that Day began her historic study of mixed-race families in the United States under renowned Harvard anthropologist Earnest Hooton’s tutelage. Hooton later recalled that when he first got to know her, he was impressed by “her abilities, her admirable strength and uprightness of character.” Furthermore,

She was not only clever and intellectual, but frank and outspoken. You could talk plainly to her and receive straight, unguarded answers.

When she graduated from Radcliffe with an A.B. — her second — in 1919, the project remained incomplete.

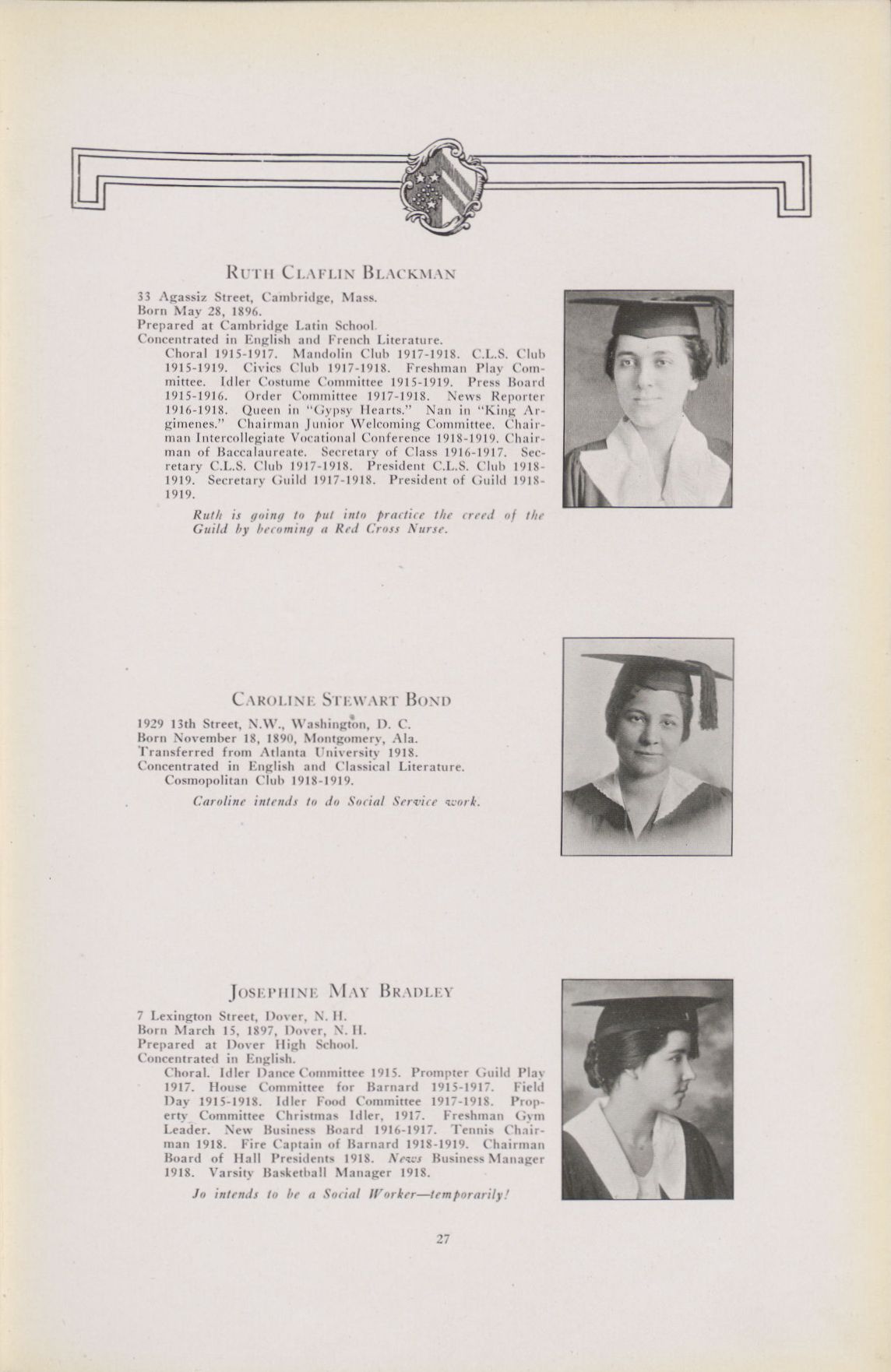

Radcliffe College Class of 1919. Cambridge, Massachusetts. 1919. Radcliffe Archives/Schlesinger Library

Radcliffe College Class of 1919. Cambridge, Massachusetts. 1919. Radcliffe Archives/Schlesinger Library

Open and scroll to read the yearbook transcript

[top of page features a decorate border with the Radcliffe shield at center]

[right: bust portrait photograph of a light skinned young woman in graduation cap and gown]

[to the left of the photo]

RUTH CLAFLIN BLACKMAN

13 Agassiz Street, Cambridge, Mass.

Born May 28, 1896.

Prepared at Cambridge Latin School.

Concentrated in English and French Literature.

Choral 1915-1917. Mandolin Club 1917-1918. C.L.S. Club 1915-1919. Civics Club 1917-1918. Freshman Play Committee. Idler Costume Committee 1915-1919. Press Board 1915-1916. Order Committee 1917-1918. News Reporter 1916-1918. Queen in “Gypsy Hearts.” Nan in “King Argimenes.” Chairman Junior Welcoming Committee. Chairman Intercollegiate Vocational Conference 1918-1919. Chairman of Baccalaureate. Secretary of Class 1916-1917. Secretary C.L.S. Club 1917-1918. President of C.L.S. Club 1918-1919. Secretary Guild 1917-1918. President of Guild 1918-1919.

Ruth is going to put into practice the creed of the Guild by becoming a Red Cross Nurse.

[right: bust portrait photograph of a light skinned young woman with wavy hair pulled back beneath a graduation cap and gown]

[to the left of the photo]

CAROLINE STEWART BOND

1929 135th Street, N.W., Washington, D. C.

Born November 18, 1890, Montgomery, Ala.

Transferred from Atlanta University 1918.

Concentrated in English and Classical Literature.

Cosmopolitan Club 1918-1919.

Caroline intends to do Social Service work.

[right: profile portrait photograph of a light skinned young woman in graduation cap and gown]

[to the left of the photo]

JOSEPHINE MAY BRADLEY

7 Lexington Street, Dover, N. H.

Born March 15, 1897, Dover, N. H.

Prepared at Dover High School.

Concentrated in English.

Choral. Idler Dance Committee 1915. Prompter Guild Play1917. House Committee for Barnard 1915-1917. Field Day 1915-1918. Idler Food Committee 1917-1918. Property Committee Christmas Idler, 1917. Freshman Gym Leader. New Business Board 1916-1917. Tennis Chairman 1918. Fire Captain of Barnard 1918-1919. Chairman Board of Hall Presidents 1918. News Business Manager 1918. Varsity Basketball Manager 1918.

Jo intends to be a Social Worker — temporarily!

[end of page]

As with other students who held degrees from historically Black colleges and universities in the late 19th and early 20th century, Caroline Bond Day’s senior profile in the Radcliffe Year Book ignored her previous degree and listed her as a transfer student./Schlesinger Library

After graduating, Day returned to New York to work at the national YWCA. The following year she married Aaron R. Day Jr. and joined him in Texas, where he taught chemistry at Prairie View State College (now Prairie View A&M University). Day found teaching positions of her own, first at the historically Black Paul Quinn College and later as head of the English Department at Prairie View. The couple moved to Georgia in 1922, where she taught English and directed theater productions at her alma mater, Atlanta University.

Finishing What She Started

During the 1927–28 and 1929–30 academic years, Hooton secured funding from the Bureau of International Research at Harvard and from Radcliffe College to fund Day’s return to Cambridge. She took leave from her position at Atlanta University to continue her earlier anthropological research at Radcliffe.

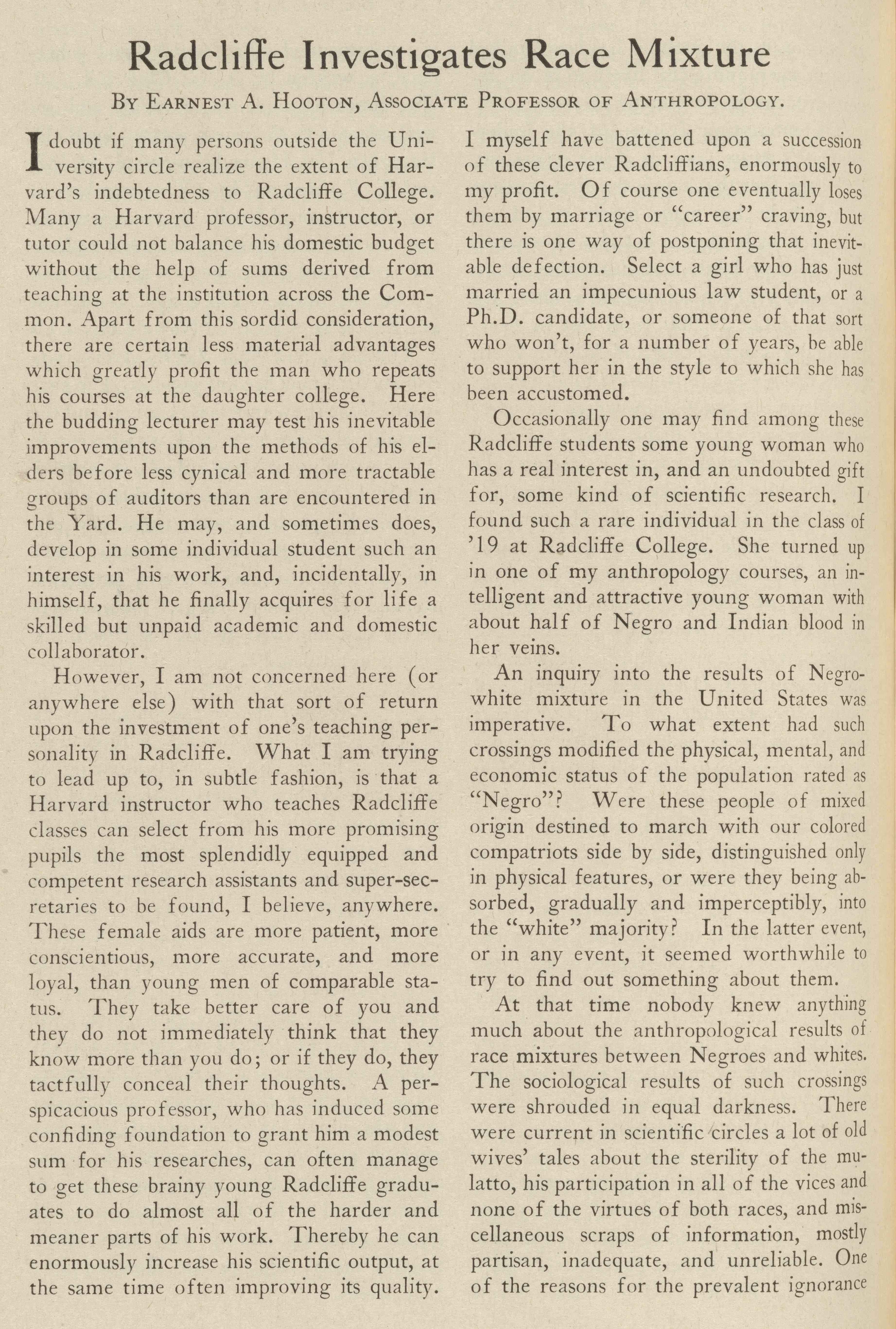

Writing about Day’s work, Hooton acknowledged that Black Americans were an “inaccessible class” for white anthropologists — and justly so:

Naturally, these colored Americans suspected the motives of the white investigator and were not only reluctant, but entirely unwilling, to submit themselves and their family history to his scrutiny. For these people have been the victims of a terrible social injustice and they have grown to expect only the worst.

Day, by contrast, was able to leverage her personal connections and her extended social networks to recruit participants. Her groundbreaking study ultimately included more than 2,500 multiracial individuals from 346 families, including her own. Exercising what Hooton described as “infinite tact and patience,” she recorded physical measurements and other descriptions, such as skin color and hair texture, and conducted in-depth interviews with her subjects about their family backgrounds and personal experiences. Many participants entrusted her with “treasured photos,” hair samples, and family stories that could be both deeply personal and difficult to share.

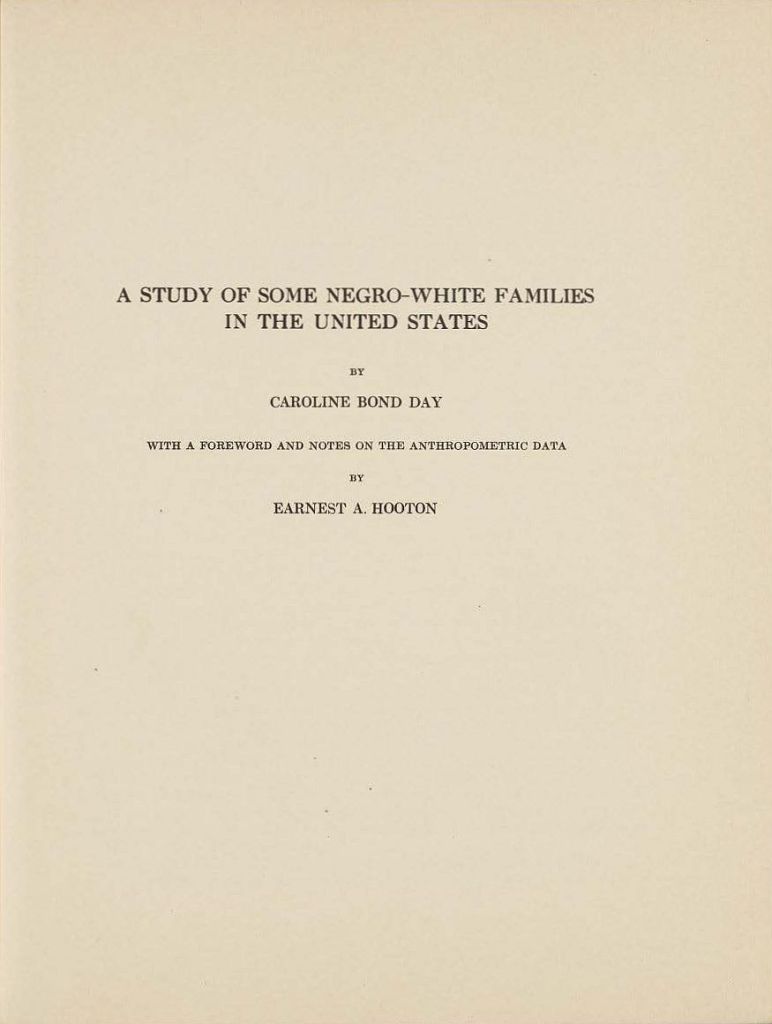

Day’s thesis, A Study of Some Negro-White Families in the United States, was published in 1932 by the Peabody Museum of Harvard University as part of a Harvard African Studies series. Pushing back against the race scientists and eugenicists at Harvard and beyond, Day’s highly technical work used the same tools deployed by racist scientists to demonstrate that race is not a fixed category and that people of color are not, as a group, inferior to whites by any measure. Her work is still hailed today as a groundbreaking.

Open and scroll to read the article transcript

Radcliffe Investigates Race Mixture

BY EARNEST A. HOOTON, ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF ANTHROPOLOGY

[text presented in two columns]

I doubt if many persons outside the University circle realize the extent of Harvard’s indebtedness to Radcliffe College. Many a Harvard professor, instructor, or tutor could not balance his domestic budget without the help of sums derived from teaching at the institution across the Common. Apart from this sordid consideration, there are certain less material advantages which greatly profit the man who repeats his courses at the daughter college. Here the budding lecturer may test his inevitable improvements upon the methods of his elders before less cynical and more tractable groups of auditors than are encountered in the Yard. He may, and sometimes does, develop in some individual student such an interest in his work, and, incidentally, in himself, that he finally acquires for life a skilled but unpaid academic and domestic collaborator.

However, I am not concerned here (or anywhere else) with that sort of return upon the investment of one’s teaching personality in Radcliffe. What I am trying to lead up to, in subtle fashion, is that a Harvard instructor who teaches Radcliffe classes can select from his more promising pupils the most splendidly equipped and competent research assistants and super-secretaries to be found, I believe, anywhere. These female aids are more patient, more conscientious, more accurate, and more loyal, than young men of comparable status. They take better care of you and they do not immediately think that they know more than you do; or if they do, they tactfully conceal their thoughts. A perspicacious professor, who has induced some confiding foundation to grant him a modest sum for his researches, can often manage to get these brainy young Radcliffe graduates todo almost all of the harder and meaner parts of his work. Thereby he can enormously increase his scientific output, at the same time often improving its quality. I myself have battened upon a succession of these clever Radcliffians, enormously to my profit. Of course one eventually loses them by marriage or “career” craving, but there is one way of postponing that inevitable defection. Select a girl who has just married an impecunious law student, or a Ph.D. candidate, or someone of that sort who won’t, for a number of years, be able to support her in the style to which she has been accustomed.

Occasionally one may find among these Radcliffe some young woman who has a real interest in, and an undoubted gift for, some kind of scientific research. I found such a rare individual in the class of ’19 at Radcliffe College. She turned up in one of my anthropology courses, an intelligent young woman with about half of Negro and Indian blood in her veins.

An inquiry into the results of Negro-white mixture in the United States was imperative. To what extent had such crossings modified the physical, mental, and economic status of the population rated as “Negro”? Were these people of mixed origin destined to march with our colored compatriots side by side, distinguished only in physical features, or were they being absorbed, gradually and imperceptibly, into the “white” majority? In the latter event, or in any event, it seemed worthwhile to try to find out something about them.

At that time nobody knew anything much about the anthropological results of race mixtures between Negroes and whites. The sociological results of such crossings were shrouded in equal darkness. There were current in scientific circles a lot of old wives’ tales about the sterility of the mulatto, his participation in all of the vices and none of the virtues of both races, and miscellaneous scraps of information, mostly partisan, inadequate, and unreliable. One of the reasons for the prevalent ignorance

[end of page]

Day’s advisor Earnest Hooton published an article about her research shortly before Day received her master’s degree in 1930. While he praised her abilities at great length, his condescending attitude toward women scholars hints at some of the challenges Day faced in completing her extraordinary study. “Radcliffe Investigates Race Mixture.” Harvard Alumni Bulletin vol. 32. April 3, 1930/Harvard University Archives

Open and scroll to read the article transcript

[page header] HARVARD ALUMNI BULLETIN

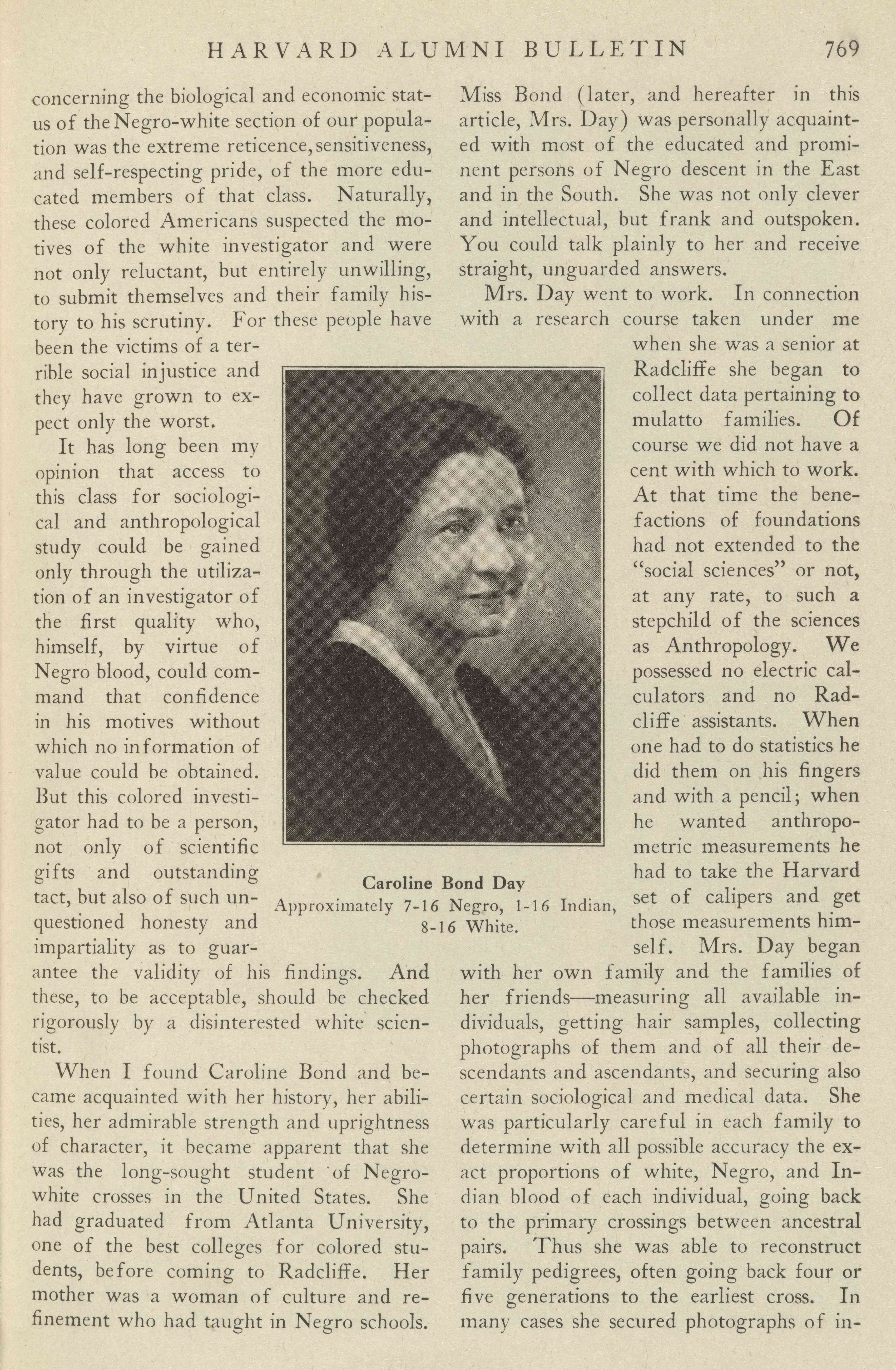

[centered on the page between two columns of text is a black and white bust portrait of a light skinned young woman in one-quarter profile]

[image caption]

Caroline Bond Day

Approximately 7-16 Negro, 1-16 Indian, 8-16 White.

[text presented in two columns]

concerning the biological and economic status of the Negro-white section of our population was the extreme reticence, sensitiveness, and self-respecting pride, of the more educated members of that class. Naturally, these colored Americans suspected the motives of the white investigator and were not only reluctant, but entirely unwilling, to submit themselves and their family history to scrutiny. For these people have been the victims of a terrible social injustice and they have grown to expect only the worst.

It has long been my opinion that access to this class for sociological and anthropological study could be gained only through the utilization of an investigator of the first quality who, himself, by virtue of Negro blood, could command that confidence in his motives without which no information of value could be obtained. But this colored investigator had to be a person, not only of scientific gifts and outstanding tact, but also of such unquestioned honesty and impartiality as to guarantee the validity of his findings. And these, to be acceptable, should be checked rigorously by a disinterested white scientist.

When I found Caroline Bond and became acquainted with her history, her abilities, her admirable strength of character, it became apparent that she was the long-sought student of Negro-white crosses in the United States. She had graduated from Atlanta University, one of the best colleges for colored students, before coming to Radcliffe. Her mother was a woman of culture and refinement who had taught in Negro schools. Miss Bond (later, and hereafter in this article, Mrs. Day) was personally acquainted with most of the educated and prominent persons of Negro descent in the East and in the South. She was not only clever and intellectual, but frank and outspoken. You could talk plainly to her and receive straight, unguarded answers.

Mrs. Day went to work. In connection with a research course taken under me when she was a senior at Radcliffe she began to collect data pertaining to mulatto families. Of course we did not have a cent with which to work. At that time the benefactions of foundations had not extended to the “social sciences” or not, at any rate, to such a stepchild of the sciences as Anthropology. We possessed no electric calculators and no Radcliffe assistants. When one had to do statistics he did them on his fingers and with a pencil; when he wanted anthropometric measurements he had to take the Harvard set of calipers and get those measurements himself. Mrs. Day began with her own family and the families of her friends — measuring all available individuals, getting hair samples, collecting photographs of them and of all their descendants and ascendants, and securing also certain sociological and medical data. She was particularly careful in each family to determine with all possible accuracy the exact proportions of white, Negro, and Indian blood of each individuals, going back to the primary crossings between ancestral pairs. Thus she was able to reconstruct family pedigrees, often going back four or five generations to the earliest cross. In many cases she secured photographs of in-[…]

[end of page; end of article excerpt]

Day included herself and members of her family as subjects of study in her research. Earnest Hooton. “Radcliffe Investigates Race Mixture.” Harvard Alumni Bulletin vol. 32. April 3, 1930/Harvard University Archives

Open and scroll to read the article transcript

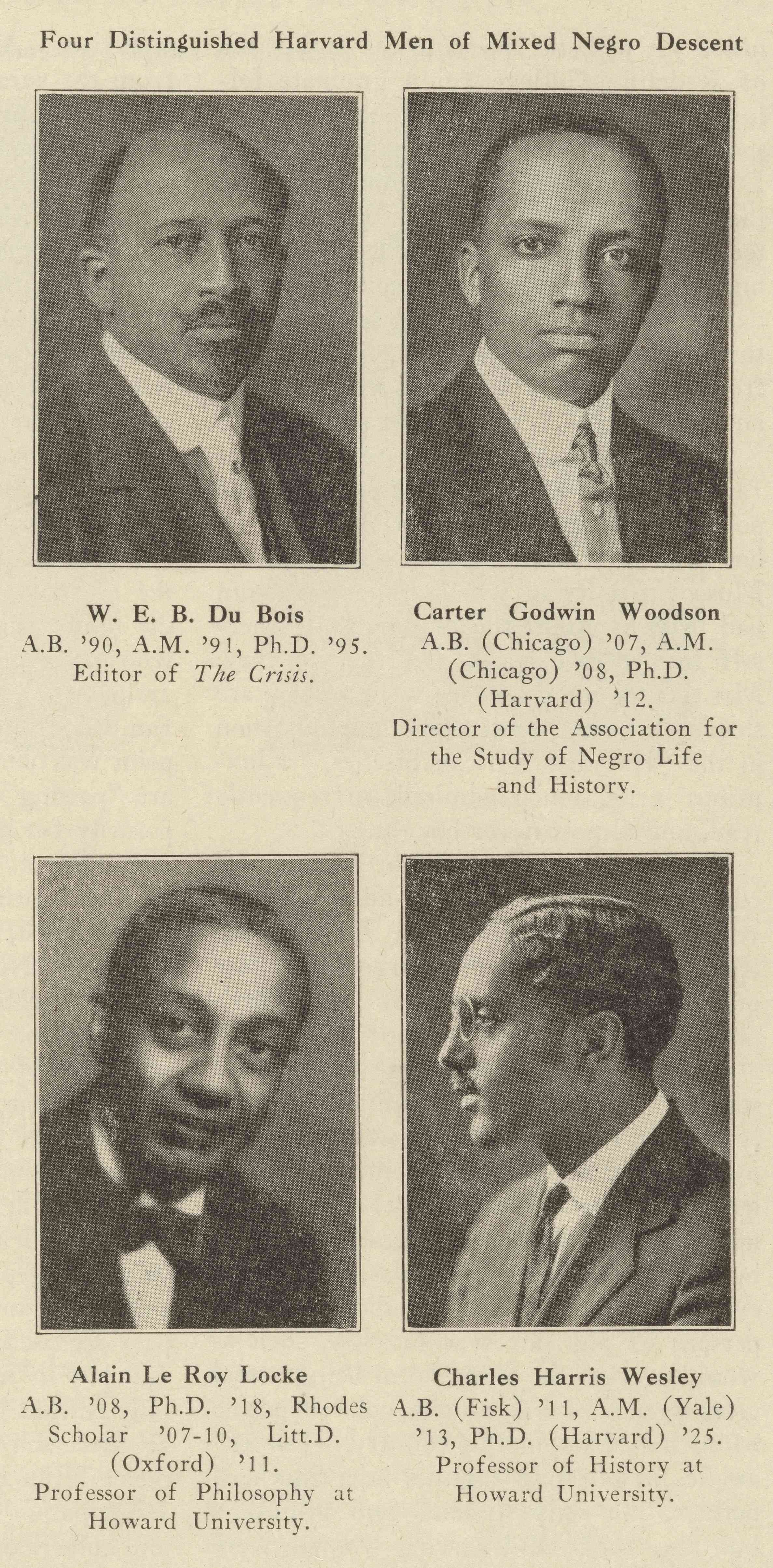

Four Distinguished Harvard Men of Mixed Negro Descent

[top left: black and white bust portrait photograph of W.E.B. Du Bois]

W.E.B. Du Bois

A.B. ’90, A.M. ’91, Ph.D. ’95.

Editor of The Crisis.

[top right: black and white bust portrait photograph of Carter G. Woodson]

Carter Godwin Woodson

A.B. (Chicago) ’07, A.M. (Chicago) ’08, Ph.D. (Harvard) ’12.

Director of the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History.

[bottom left: black and white bust portrait photograph of Alain Locke]

Alain Le Roy Locke

A.B. ’08, Ph.D. ’18, Rhodes Scholar ’07–10, Litt.D. (Oxford) ’11.

Professor of Philosophy at Howard University.

[bottom right: black and white bust portrait photograph of Charles H. Wesley]

Charles Harris Wesley

A.B. (Fisk) ’11, A.M. (Yale) ’13, Ph.D. (Harvard) ’25.

Professor of History at Howard University.

[end]

Day leveraged personal connections to recruit participants to her study, including prominent Black Harvard graduates activist and scholar W.E.B. Du Bois (A.B. 1891; A.M. 1891; Ph.D. 1895), historians Carter G. Woodson (Ph.D. 1912) and Charles H. Wesley (Ph.D. 1925), and writer Alain Locke (A.B. 1908; Ph.D. 1918). Earnest Hooton. “Radcliffe Investigates Race Mixture.” Harvard Alumni Bulletin vol. 32. April 3, 1930/Harvard University Archives

Open and scroll to read the article transcript

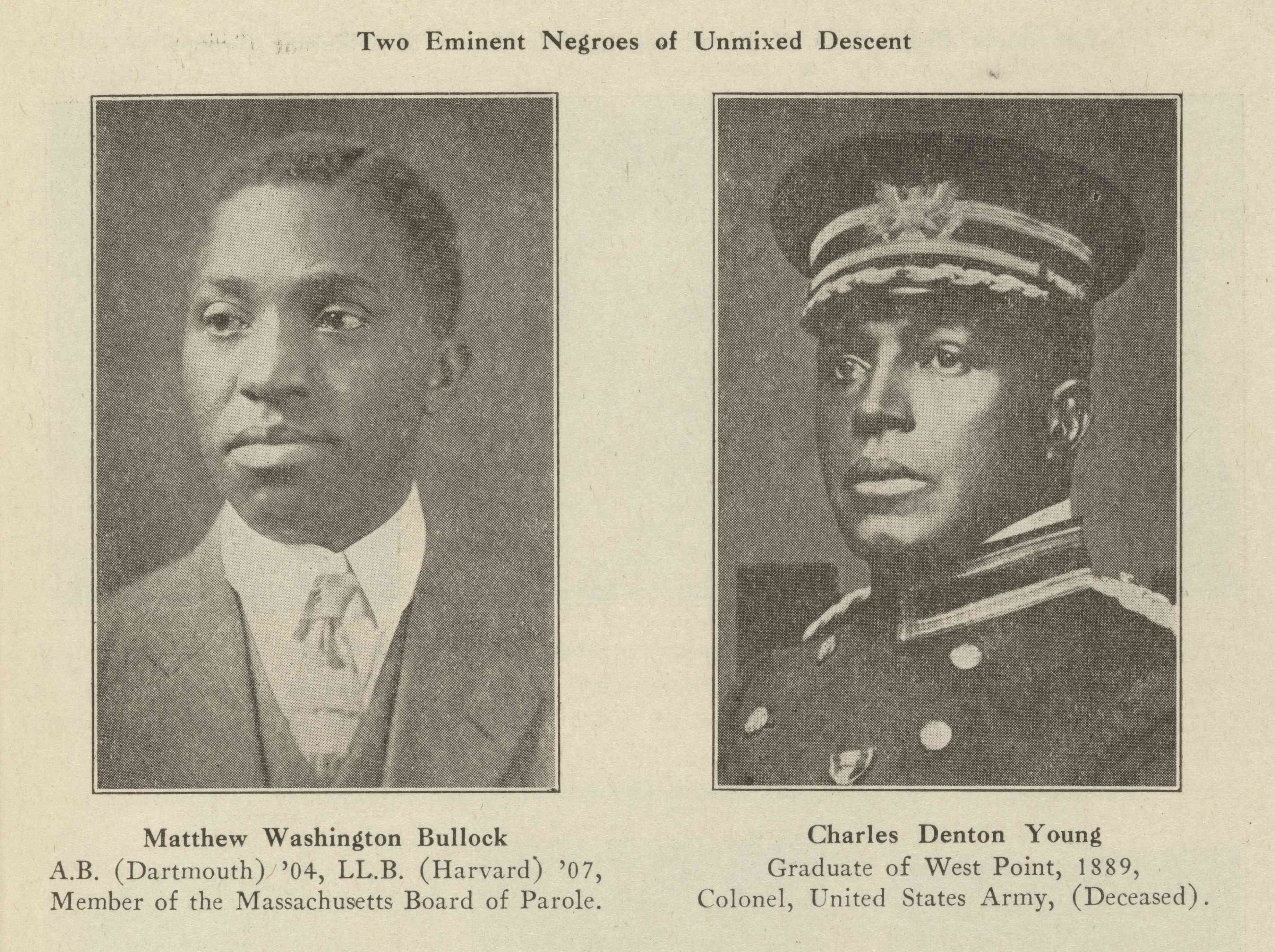

Two Eminent Negroes of Unmixed Descent

[left: black and white bust portrait photograph of Matthew W. Bullock]

Matthew Washington Bullock

A.B. (Dartmouth) ’04, LL.B. (Harvard) ’07,

Member of the Massachusetts Board of Parole.

[right: black and white bust portrait photograph of Col. Charles Young]

Charles Denton Young

Graduate of West Point, 1889,

Colonel, United States Army, (Deceased).

[end]

Hooton, like Day, was interested in highlighting accomplished and respected Black people with no discernible white ancestors — thus demonstrating, contrary to the popular beliefs of most eugenicists at the time, that Black excellence was not the result of mixed-race ancestry that included whites. Earnest Hooton. “Radcliffe Investigates Race Mixture.” Harvard Alumni Bulletin vol. 32. April 3, 1930/Harvard University Archives

Open and scroll to read the article transcript

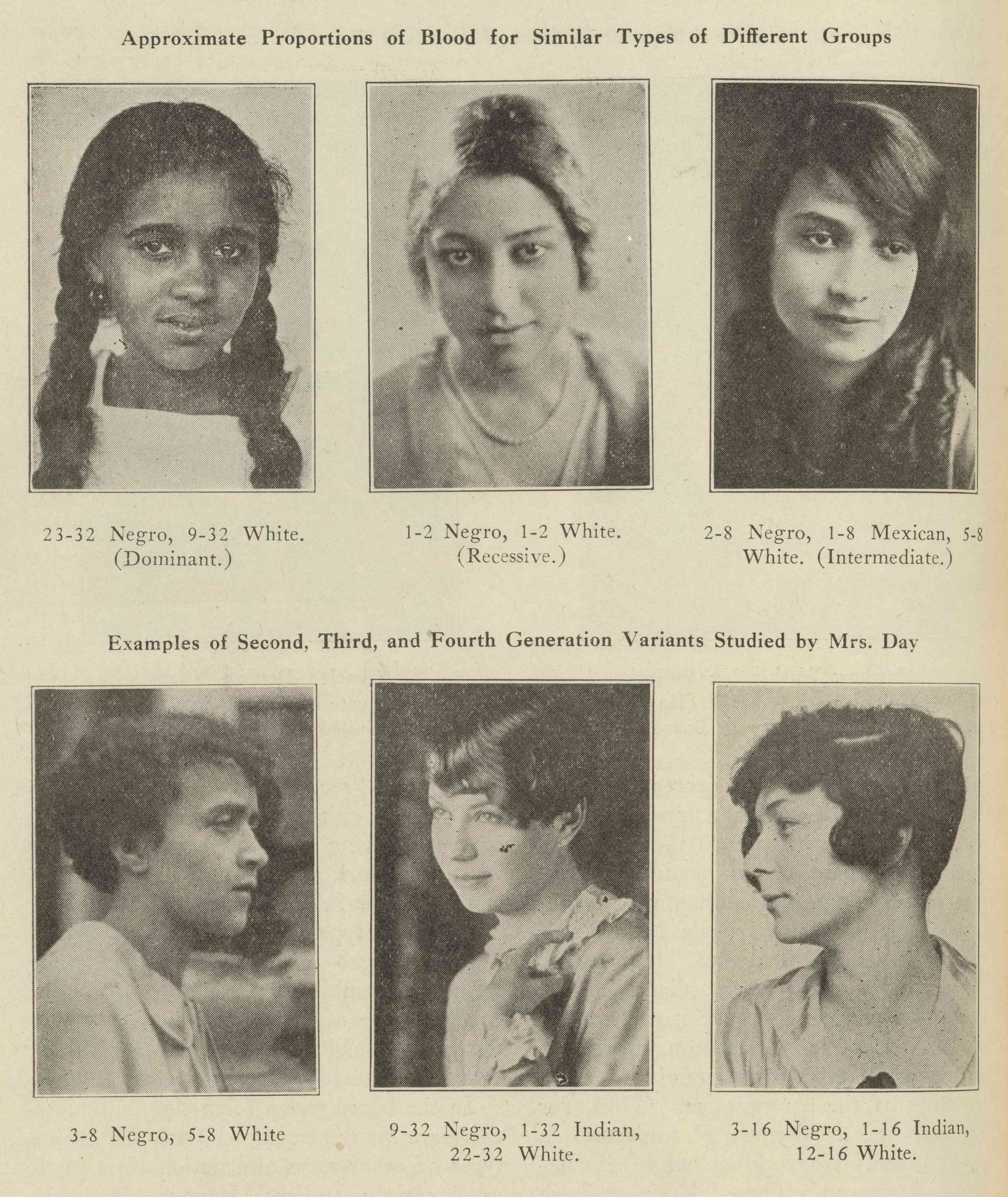

Approximate Proportions of Blood for Similar Types of Different Groups

[left: black and white bust portrait photograph of a young girl with dark skin, dark eyes, and dark hair in two long braids]

23-32 Negro, 9-32 White.

(Dominant.)

[center: black and white bust portrait photograph of a young girl with light skin, dark eyes, and straight hair pulled back from her face]

1-2 Negro, 1-2 White.

(Recessive.)

[right: black and white bust portrait photograph of a young girl with light skin, dark eyes, and dark hair falling in ringlets over her shoulders]

2-8 Negro, 1-8 Mexican, 5-8 White.

(Intermediate.)

Examples of Second, Third, and Fourth Generation Variants Studied by Mrs. Day

[right: black and white bust portrait photograph of a young girl with light skin and short dark curly hair]

3-8 Negro, 5-8 White.

[center: black and white bust portrait photograph of a young girl with very light skin, light eyes, and short dark straight hair]

9-32 Negro, 1-32 Indian, 22-32 White.

[right: black and white profile portrait photograph of a young girl with light skin and short dark wavy hair]

3-16 Negro, 1-16 Indian, 12-16 White.

[end of transcriptions from this article]

Hooton noted without judgement that people of African ancestry often could and did hide their race and live as white, often in order to get higher paying jobs than were available to Black people. Day documented that 35 of the 346 families in the study including at least one member who was “passing for white.” “Radcliffe Investigates Race Mixture.” Harvard Alumni Bulletin vol. 32. April 3, 1930/Harvard University Archives

Day’s study demonstrated that “race is not a fixed category and that by no measure are people of color as a group inferior to whites.” Hooton wrote that, for Day, “this study is a mission.” “Radcliffe Investigates Race Mixture.” Harvard Alumni Bulletin vol. 32. April 3, 1930/Harvard University Archives

A Lifetime Commitment to Community Service

While Day’s research is still recognized as groundbreaking today, she never held a full-time position in anthropology. From 1930 to 1933 she taught English at Howard University, before returning to social work and community philanthropy. In 1934, she accepted the role of director of the Southeast Settlement House, described by the Washington Times as “established in that section of the city for the last four years for social work among colored people.” In 1937, she became a leader of the historic Phyllis Wheatley YWCA in Washington, DC, as general secretary.

Creative Work

Literature was a constant in Day’s life; she won a prize for a short story when she was a high school student at Tuskegee, and continued to publish stories and essays throughout her life in Black literary magazines like Opportunity: Journal of Negro Life and the NAACP’s The Crisis.

Perhaps most notably “The Pink Hat,” published in 1926 and recognized with third prize in the National Urban League’s short story competition, explores questions of identity as well as the discrimination faced by mixed-race Black Americans like her. In the poignant short story, a light-skinned protagonist named Sarah discovers that, when wearing a particular pink straw hat as she goes about her daily life in a southern city, she is routinely mistaken for white. She takes advantage of her discovery to experience life as a white woman, enjoying access to segregated spaces and simple kindness from white strangers.

“It is at once my magic-carpet, my enchanted cloak, my Aladdin’s lamp,” says Sarah. But the magic ends when she falls and breaks an ankle while leaving a play at a local university. Homebound with her “colored family” in a “colored section of town,” Sarah is once again refused service — this time by the doctor she sought to treat her injury. When she has finally recovered and returned to work, the pink hat becomes “useless” as she finds new joy in her family, her students, and her community. Her “brown boys and girls” are again “reservoirs of interest,” and she celebrates that one of them is off to Radcliffe. She concludes: “Health, a job, young minds and souls to touch, a friend, some books, a child, a garden, Spring! Who’d want a hat?”

Final Years

In 1939, the Days moved to Durham, North Carolina, where her husband led an office of the Black-owned North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance Company and Caroline taught English and drama at the North Carolina College for Negroes (now North Carolina Central University). Her continuing struggles with chronic illness forced her to retire soon thereafter. She died in 1948.

Legacies

Caroline Bond Day paved the way for many women in her family to make outstanding contributions in social work, scholarship, teaching, and the arts. Like Day, each of these remarkable women have fostered greater understanding of and appreciation for Black history and culture in the United States.

Her sister, Wenonah Bond Logan, studied sociology at Atlanta University and Boston University, and earned a Masters degree in social work from Columbia University. Supported by a fellowship, she spent a year in Denmark and Great Britain studying international sociology, returning to the U.S. in 1931 and to work in social services. During her long career, she worked for the New York state employment service, the National Social Welfare Assembly, and the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA), where she eventually served as the national associate general secretary.

Logan’s daughter Adele Logan Alexander followed her aunt to Radcliffe, where she earned an A.B. in 1955 and met her future husband, Harvard graduate Clifford Alexander Jr. (A.B. 1955) — who went on to become chairman of the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (1967–1969) and the first Black American secretary of the Army (1977–1981). After nearly 30 years of marriage and two children, she entered Howard University and earned her Ph.D. in history in 1994. Dr. Alexander went on to build a career as a scholar of Black women and families in U.S. history. In her 1999 book, “Homelands and Waterways: The American Journey of the Bond Family, 1846–1926”, she explored her family’s journey from slavery to the middle class, including Day’s journey at Radcliffe.

Alexander’s daughter is renowned poet and scholar Elizabeth Alexander, who holds degrees from Yale University, Boston University, and the University of Pennsylvania, where she earned her Ph.D. in English in 1992. Alexander, who read an original poem at the first inauguration of President Barack Obama in 2009, has held teaching positions at the University of Chicago, Smith College, Yale University, and Columbia University, and was a 2007–2008 Fellow at the Harvard Radcliffe Institute. She is currently the president of the Mellon Foundation. In 2006, Alexander was the Phi Beta Kappa poet at Literary Exercises held by the organization’s Harvard chapter. Her original “Poem of a Thousand Stories” celebrated the importance of every individual’s story, and highlighted the achievements of her great-aunt Caroline Bond Day.

Selected Sources

Alexander, Adele Logan. Homelands and Waterways: The American Journey of the Bond Family, 1846-1926. New York: Pantheon Books, 2000.

Caroline Bond Day papers, 993–21;994–22. Peabody Museum Archives.

“Caroline Bond Day.” In Blacks at Harvard: A Documentary History of African-American Experience At Harvard and Radcliffe, ed. Werner Sollors et al., 169–188. New York, NY: NYU Press, 1993.

“Caroline Bond Day.” The Report of the Presidential Committee on Harvard & the Legacy of Slavery. Harvard Radcliffe Institute. Accessed July 10, 2023.

Curwood, Anastasia C. 2012. “Caroline Bond Day (1889-1948): A Black Woman Outsider Within Physical Anthropology.” Transforming Anthropology 20 (1): 79–89.

Day, Caroline Bond. “The Pink Hat.” Opportunity: A Journal of Negro Life 4, no. 48 (Dec. 1926), 379–380.

Parker, Lonnae O’Neal. “Repeating Family History: the National Book Festival’s Adele and Elizabeth Alexander are both Blood and Ink Relations.” The Washington Post, Sep 25, 2010.

More profiles

Alberta Virginia Scott

Alberta Virginia Scott created a quietly powerful legacy as the first Black woman to graduate from Radcliffe College.

Frances O. Grant

Frances O. Grant, the first Black woman elected to the Iota Chapter of Phi Beta Kappa, graduated from Radcliffe College in 1917. She went on to an extraordinary career as an educator, primarily at the…

Eva B. Dykes

Eva Beatrice Dykes made history at Radcliffe College in 1921 as the first Black woman to complete the requirements for a Ph.D. in the United States.