Marita Bonner

Class of 1922

Marita Bonner

Marita Bonner Occomy, an award-winning author and song writer who published under her maiden name Marita Bonner, graduated from Radcliffe College in 1922.

School: Radcliffe College

Degree: A.B.

Area of Impact: Arts

HBCU Affiliation:

Bluefield State University

A Born Writer

Born in Boston on July 16, 1899, Marita Bonner grew up in nearby Brookline, Massachusetts. She attended Brookline High School where, as a budding writer, she contributed to the school magazine The Sagamore. Following graduation in 1918, she enrolled at Radcliffe College.

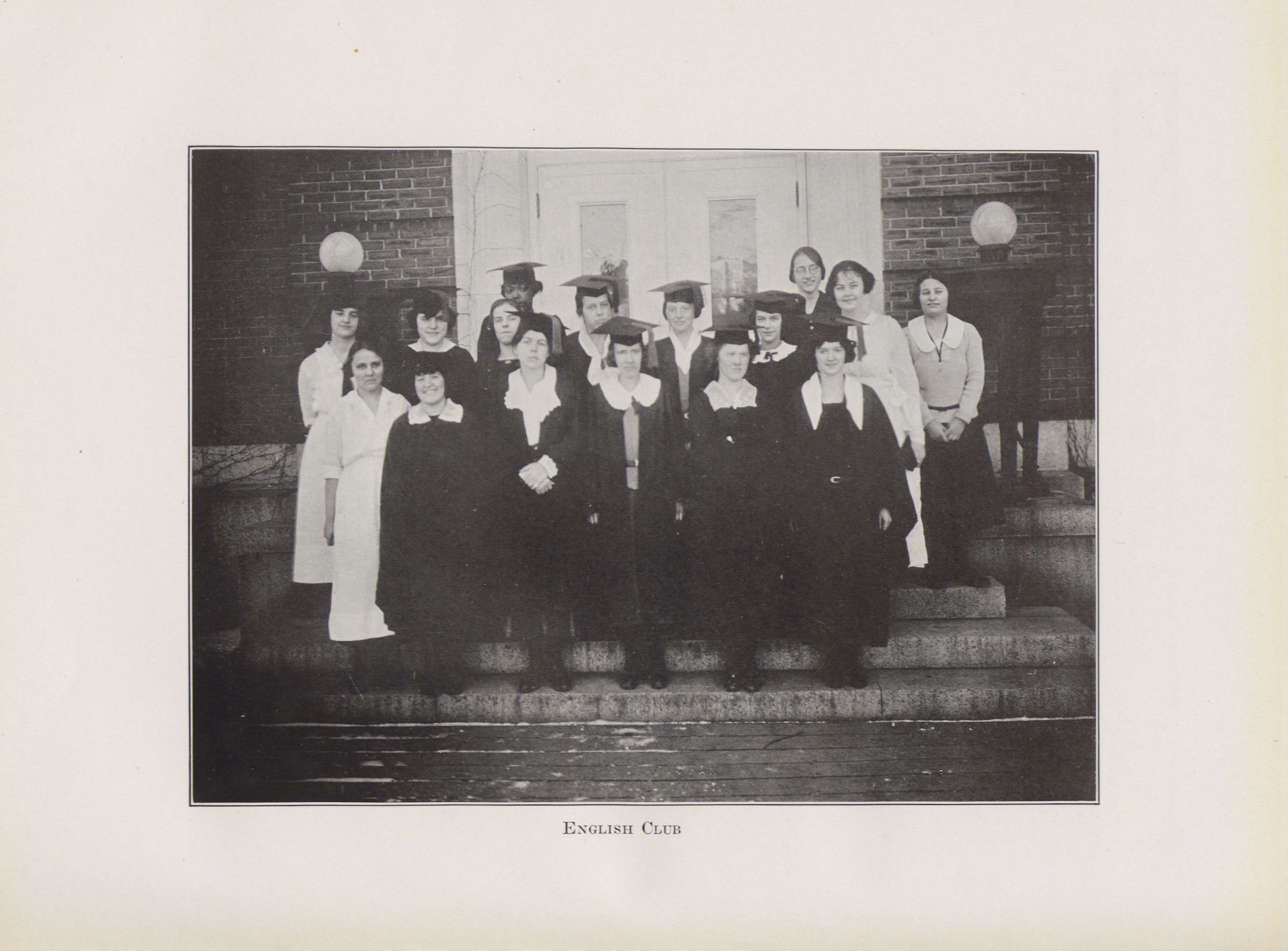

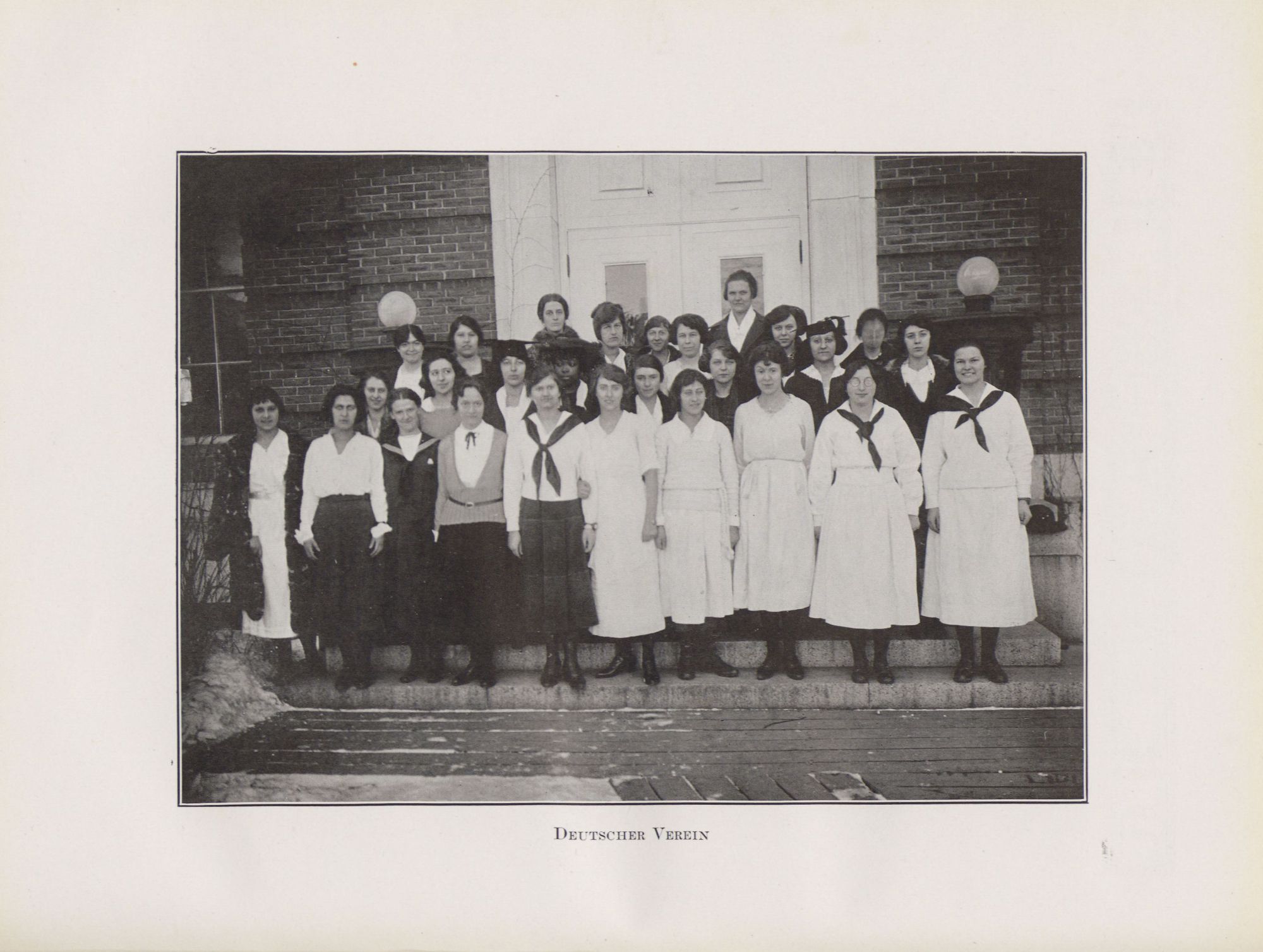

Bonner studied English and Comparative Literature at Radcliffe, and was active in campus life as a member of the Music Club, the Mandolin Club, the German Club, and the English Club. But because Black students were not allowed to live in campus dormitories, she had to commute to Radcliffe from several miles away in the Boston neighborhood of Roxbury.

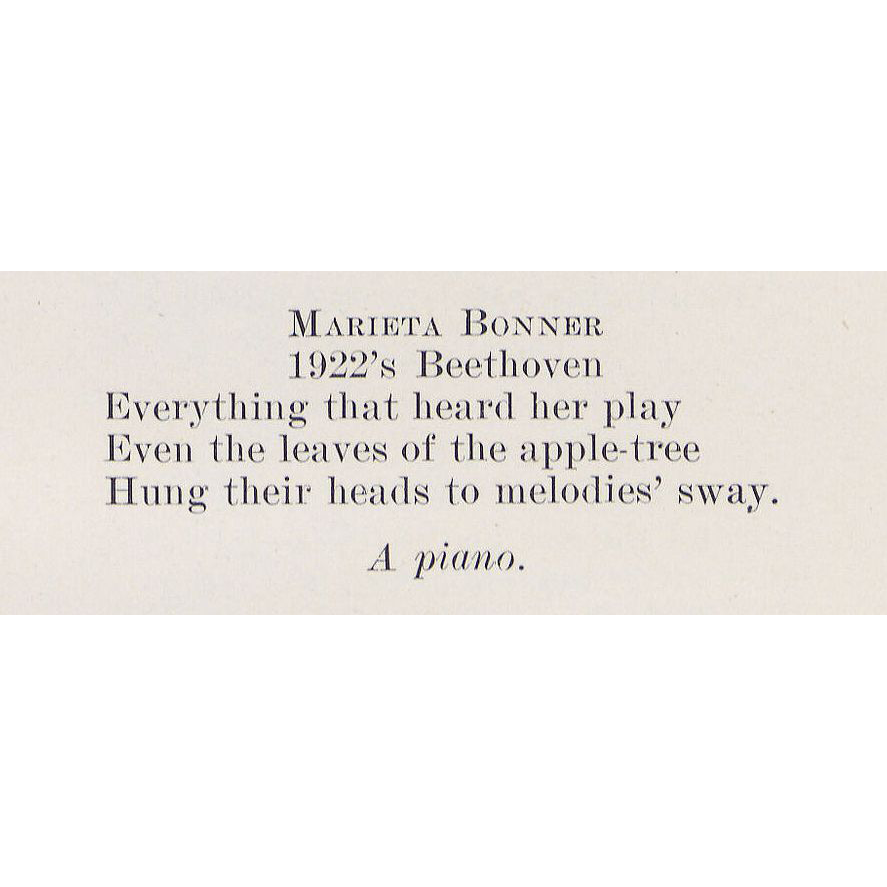

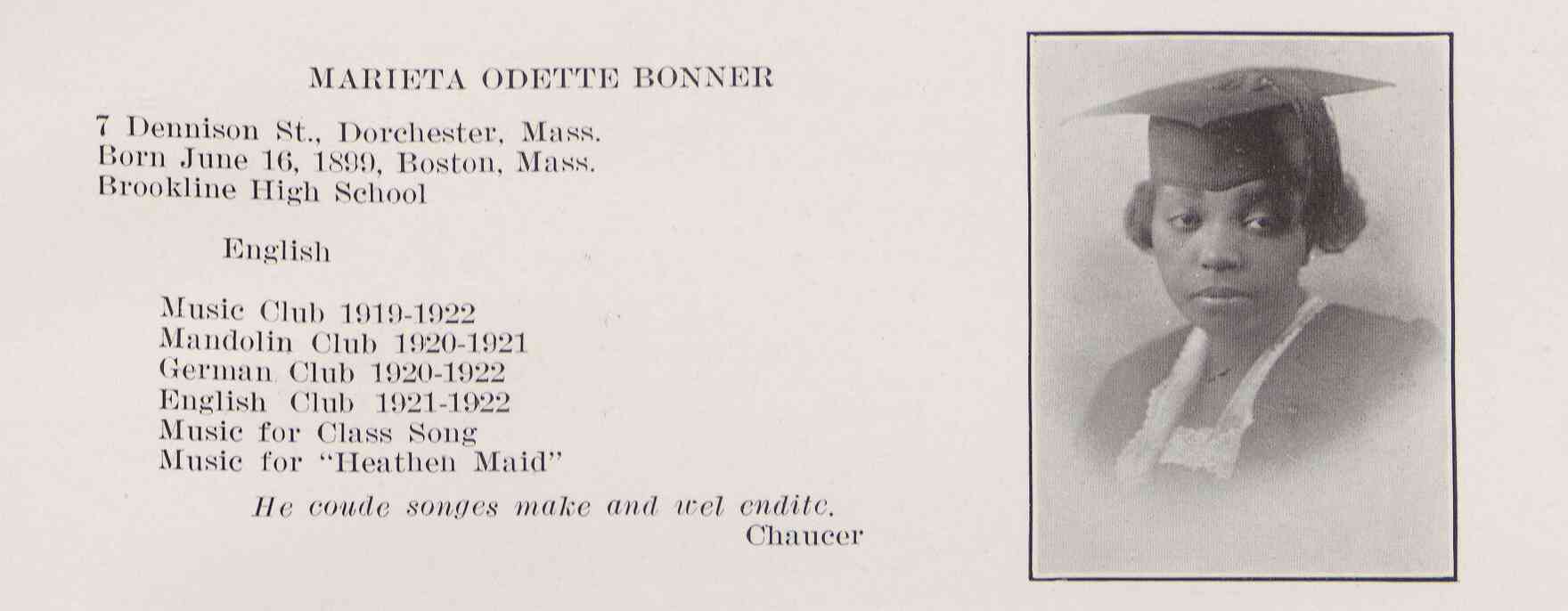

Yearbook transcript

[At right: Black and white head-and-shoulders photograph of Marita Bonner in graduation cap.]

[At left, alongside photograph]

MARIETA ODETTE BONNER

7 Dennison St., Dorchester, Mass.

Born June 16, 1899, Boston, Mass.

Brookline High School

English

Music Club 1919-1922

Mandolin Club 1920-1921

German Club 1920-1922

English Club 1921-1922

Music for Class Song

Music for “Heathen Maid”

He coude songes make and wel endite.

Chaucer

[end of year book entry]

Marita Bonner’s senior profile in the 1922 Radcliffe Year Book misspelled her name and incorrectly listed her address as Dorchester, a predominantly Black Boston neighborhood adjacent to her own neighborhood of Roxbury./Schlesinger Library

Young, Gifted — and Black

A gifted composer and pianist since high school, Bonner was praised in a Radcliffe class poem as “1922’s Beethoven.” She composed the music for the winning songs in the Radcliffe song competitions in 1919 and 1922.

Bonner’s writing talent was also recognized, and her work was featured in the Harvard Review and the Boston Post. In her junior year, she earned a spot in the writing seminar of legendary Harvard professor Charles Townsend Copeland. “Dandelion Season,” one of the sketches she wrote during this period, was chosen to be read annually to Radcliffe classes.

Despite her obvious talents, Bonner faced obstacles to her ambitions to become a writer. She later recorded, in family papers shared by her children with scholars Lorraine Elena Roses and Ruth Elizabeth Randolph, that Professor Copeland “urged me to write — but not to be ‘bitter’ — a cliché to colored people who write.”

While Bonner engaged in many activities at Radcliffe, she was one of only a handful of Black students there. She sought — and created — community with young Black women enrolled at other local colleges and universities when she founded the Boston-area chapter of the historically Black Delta Sigma Theta Sorority.

In the winter of her senior year, Bonner had fulfilled all the requirements for her degree in just three and a half years. But because Radcliffe did not grant mid-year degrees, she continued her studies and received her bachelor’s degree in June 1922. Despite the challenges she faced at Radcliffe, she later described her childhood in Brookline and her years at the College as “the happiest days of my life.”

Open and scroll to read the document transcript

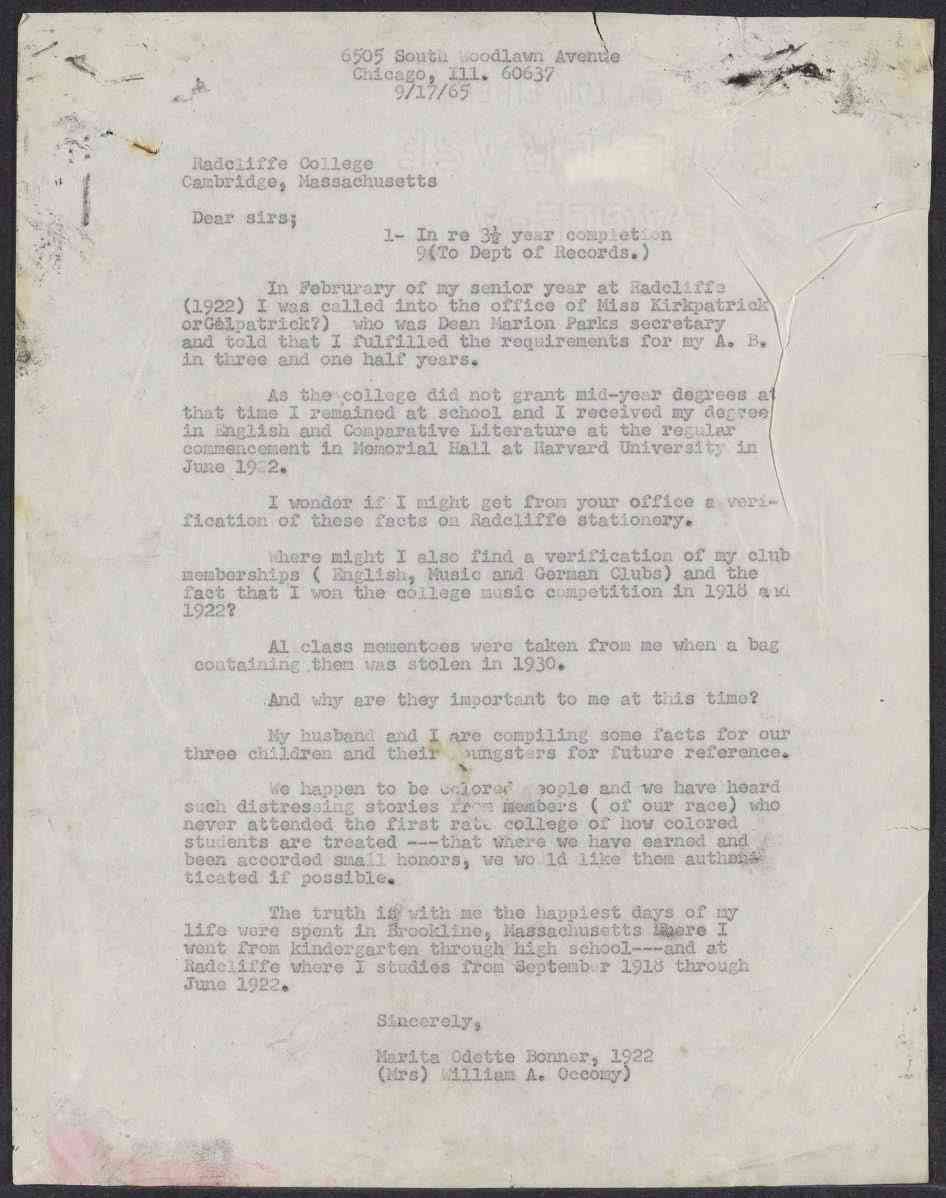

6505 South Woodlawn Avenue

Chicago, Ill. 60637

9/17/65

Radcliffe College

Cambridge, Massachusetts

Dear sirs;

1- In re 3½ year completion

9(To Dept of Records.)

In Februrary of my senior year at Radcliffe (1922) I was called into the office of Miss Kirkpatrick or Gelpatrick?) who was Dean Marion Parks secretary and told that I fulfilled the requirements for my A. B. in three and one half years.

As the college did not grant mid-year degrees at that time I remained at school and I received my degree in English and Comparative Literature at the regular commencement in Memorial Hall at Harvard University in June 1922.

I wonder if I might get from your office a verification of these facts on Radcliffe stationary.

Where might I also find a verification of my club memberships ( English, Music and German Clubs) and the fact that I won the college music competition in 1918 and 1922?

Al class mementoes were taken from me when a bag containing them was stolen in 1930.

And why are they important to me at this time?

My husband and I are compiling some facts for our three children and their youngsters for future reference.

We happen to be colored people and we have heard such distressing stories from members ( of our race) who never attended the first rate college of how colored students are treated —that where we have earned and been accorded small honors, we would like them authenticated if possible.

The truth is with me the happiest days of my life were spent in Brookline, Massachusetts where I went from kindergarten through high school—and at Radcliffe where I studies from September 1918 through June 1922.

Sincerely,

Marita Odette Bonner, 1922

(Mrs.) William A. Occomy)

[end of page]

In 1965, Bonner wrote to the Radcliffe College registrar requesting verification of her degree, activities, and awards. She was documenting her Radcliffe experiences as part of a family history to share with her children and future generations. Marita Bonner Papers, 1940–1986. Correspondence with children, with institutions, family data, 1963–1968. SC 97, folder 3. Radcliffe College Archives/Schlesinger Library

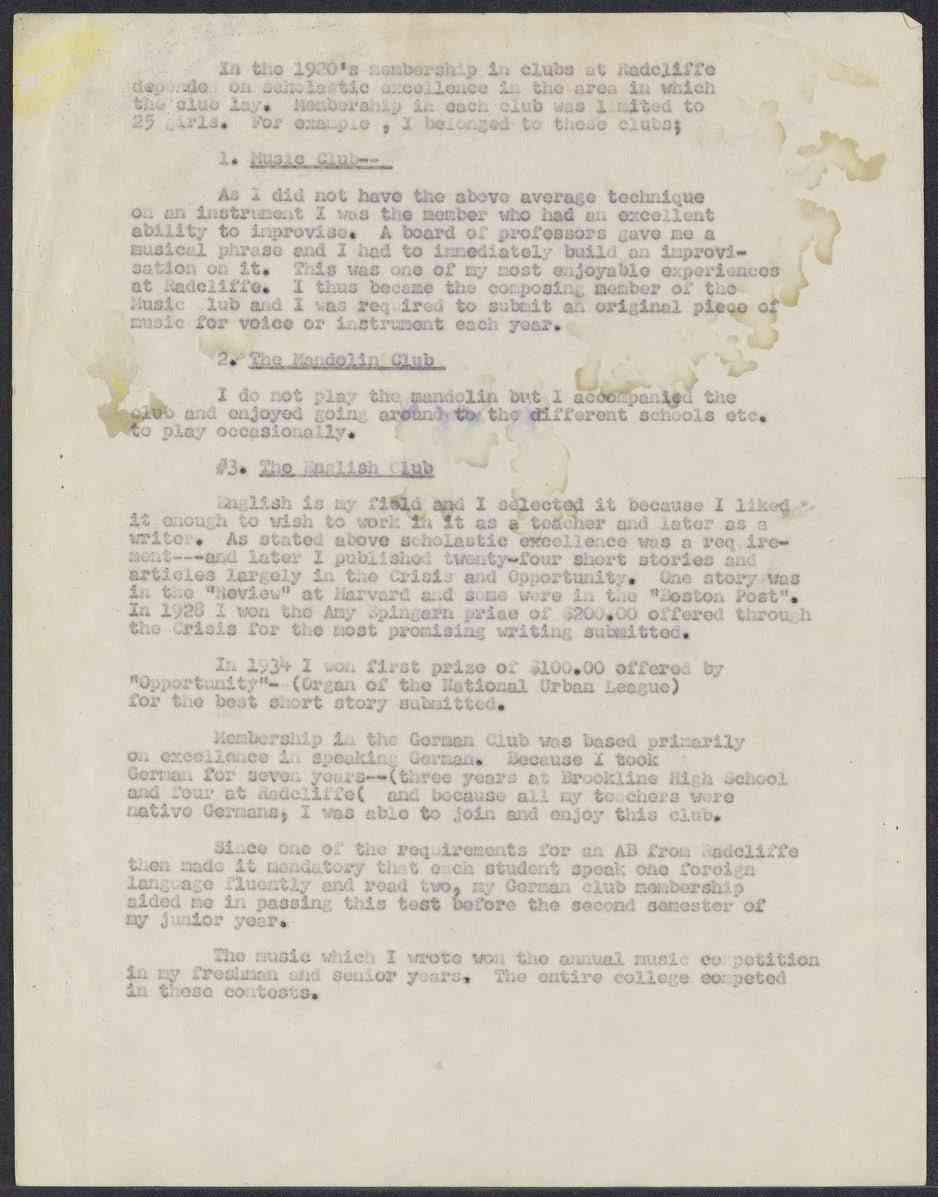

Open and scroll to read the document transcript

In the 1920’s membership in clubs at Radcliffe depended on scholastic excellence in the area in which the club lay. Membership in each club was limited to 25 girls. For example , I belonged to these clubs;

1. Music Club–

As I did not have the above average technique on an instrument I was the member who had an excellent ability to improvise. A board of professors gave me a musical phrase and I had to immediately build an improvisation on it. This was one of my most enjoyable experiences

at Radcliffe. I thus became the composing member of the Music Club and I was required to submit an original piece of music for voice or instrument each year.

2. The Mandolin Club

I do not play the mandolin but I accompanied the club and enjoyed going around to the different schools etc. to play occasionally.

#3. The English Club

English is my field and I selected it because I liked it enough to wish to work in it as a teacher and later as a writer. As stated above scholastic excellence was a requirement—and later I published twenty-four short stories and articles largely in the Crisis and Opportunity. One story was in the “Review” at Harvard and some were in the “Boston Post”. In 1928 I won the Amy Spingern prise of $200.00 offered through the Crisis for the most promising writing submitted.

In 1934 I won first prize of $100.00offered by “Opportunity”- (Organ of the National Urban League) for the best short story submitted.

Membership in the German Club was based primarily on excellence in speaking German. Because I took German for seven years–(three years at Brookline High School and four at Radcliffe( and because all my teachers were native Germans, I was able to join and enjoy this club.

Since one of the requirements for an A.B. from Radcliffe then made it mandatory that each student speak one foreign language fluently and read two, my German club membership aided me in passing this test before the second semester of my junior year.

The music which I wrote won the annual music competition in my freshman and senior years. The entire college competed in these contests.

[end of page; end of letter]

Bonner’s letter outlined her membership in the Music, Mandolin, English, and German Clubs, as well as prizes she won for both her writing and her musical compositions. Marita Bonner Papers, 1940–1986. Correspondence with children, with institutions, family data, 1963–1968. SC 97, folder 3. Radcliffe College Archives/Schlesinger Library

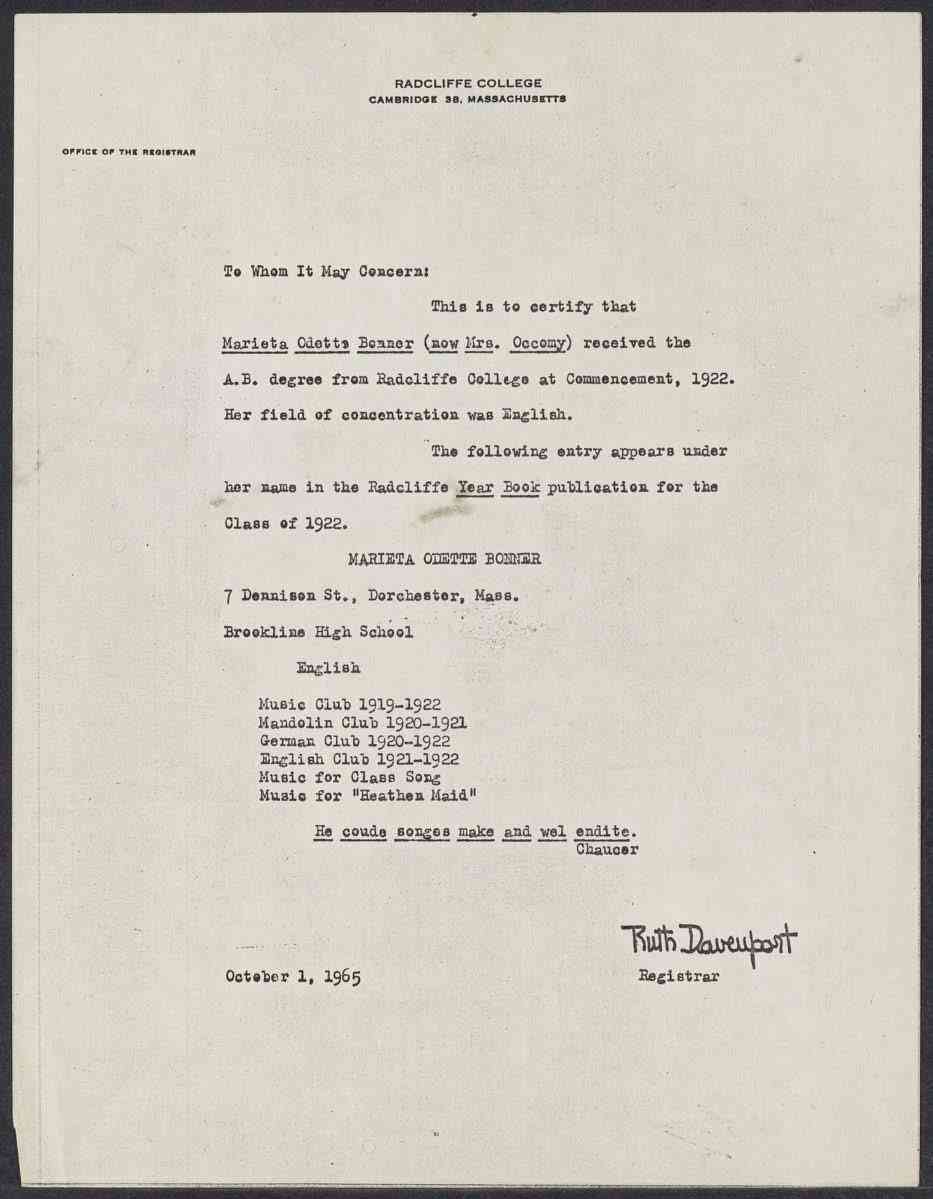

Open and scroll to read the document transcript

[preprinted letterhead]

RADCLIFFE COLLEGE

CAMBRIDGE 38, MASSACHUSETTS

OFFICE OF THE REGISTRAR

To Whom It May Concern:

This is to certify that [name underlined] Marieta Odette Bonner (now Mrs. Occomy) received the A. B. degree from Radcliffe College at Commencement, 1922. Her field of concentration was English.

The following entry appears under her name in the Radcliffe [title underlined] Year Book publication for the Class of 1922.

MARIETA ODETTE BONNER

7 Dennison St., Dorchester, Mass.

Brookline High School

English

Music Club 1919-1922

Mandolin Club 1920-1921

German Club 1920-1922

English Club 1921-1922

Music for Class Song

Music for “Heathen Maid”

[sentence underlined] He coude songes make and wel endite.

Chaucer

[stamp of signature] Ruth Davenport

Registrar

October 1, 1965

[end of letter]

The registrar referred to the 1922 Radcliffe Year Book to confirm Bonner’s memberships and song prizes. Marita Bonner Papers, 1940–1986. Correspondence with children, with institutions, family data, 1963–1968. SC 97, folder 3. Radcliffe College Archives/Schlesinger Library

Remembering Radcliffe

Bonner wrote of her time at Radcliffe in a 1965 letter to the College registrar, in which she requested a verification of her degree, club activities, and music awards. The bag in which she had stored her class mementoes had been stolen in 1930, Bonner explained, and now she hoped to document her Radcliffe experiences as she and her husband were compiling their family history to share with their children and future generations.

We happen to be colored people and we have heard such distressing stories from members (of our race) who never attended the [sic] first rate college of how colored students are treated — that where we have earned and been accorded small honors, we would like them authenticated if possible.

The experiences Bonner described were in stark contrast to the extreme racism she confronted after leaving Radcliffe in 1922. She relocated first to the segregated state of West Virginia to teach at the Bluefield Colored Institute, now Bluefield State University. In 1924, she moved to Washington, DC, where she taught at the all-Black Armstrong High School.

A Writer and a Teacher

During this period, Bonner continued to write short stories, essays, and plays. Her essay “On Being Young — A Woman — and Colored” was published in the December 1925 edition of the NAACP magazine, The Crisis, edited by W.E.B. Du Bois (A.B. 1891, Ph.D. 1895). The piece highlighted the contrasts between the happiness that young girls dream of and the harsh realities young women face as a result of discrimination — especially when they are Black.

You long to explode and hurt everything white; friendly; unfriendly. But you know that you cannot live with a chip on your shoulder even if you can manage a smile around your eyes — without getting steely and brittle and losing the softness that makes you a woman.

[…]

So — being a woman — you can wait.

You must sit quietly without a chip. Not sodden — and weighted as if your feet were cast in the iron of your soul. Not wasting strength in enervating gestures as if two hundred years of bonds and whips had really tricked you into nervous uncertainty.

The magazine awarded Bonner first prize for the essay, and two years later gave the same honor to her story “Drab Rambles.” Bonner’s writing was also featured during this period in the National Urban League’s magazine, Opportunity.

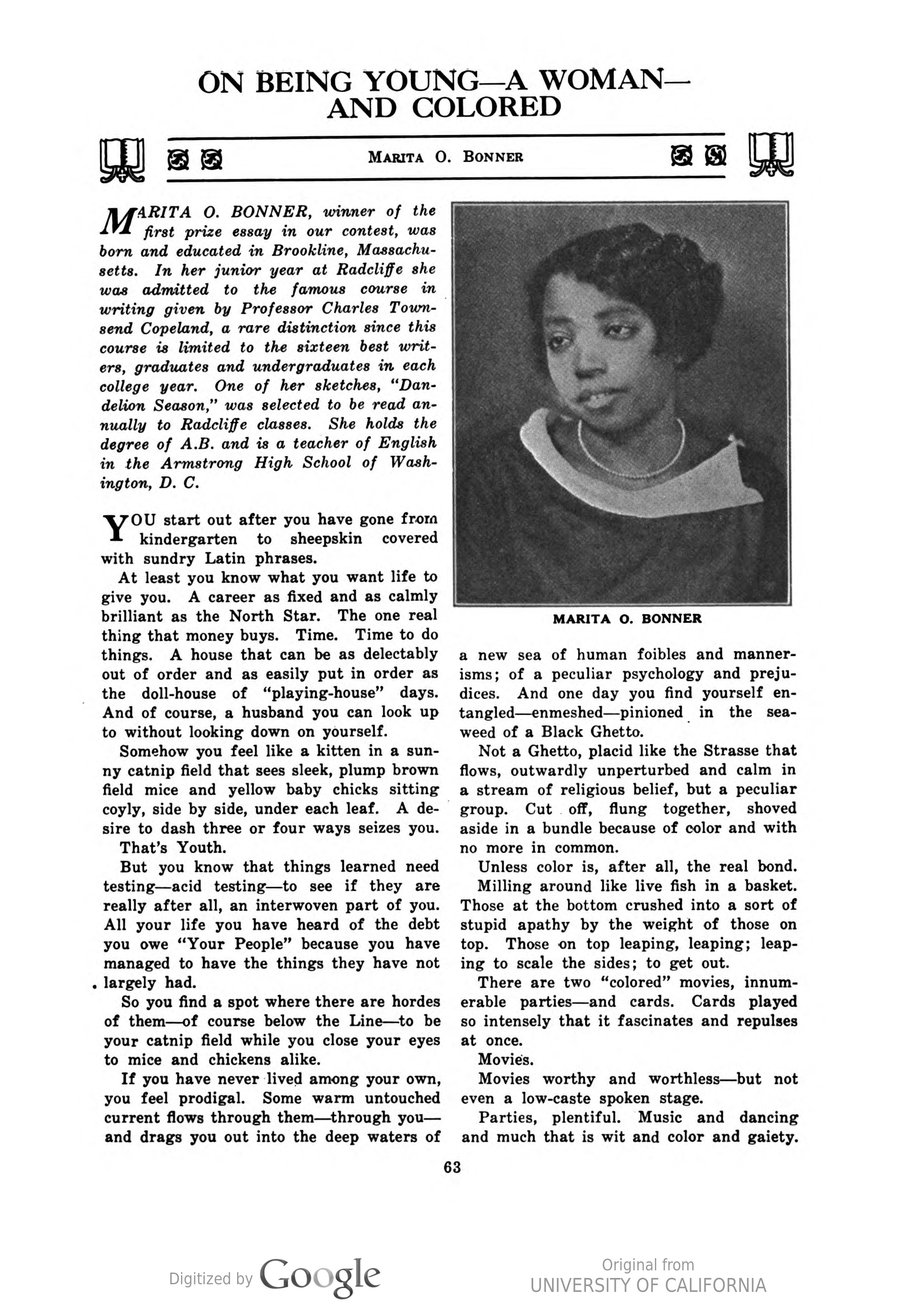

Open and scroll to read the essay transcript

ON BEING YOUNG–A WOMAN–

AND COLORED

Marita O. Bonner

Marita O. Bonner, winner of the first prize essay in our contest, was born and educated in Brookline, Massachusetts. In her junior year at Radcliffe she was admitted to the famous course in writing given by Professor Charles Townsend Copeland, a rare distinction since this course is limited to the sixteen best writers, graduates and undergraduates in each college year. One of her sketches, “Dandelion Season,” was selected to be read annually to Radcliffe classes. She holds the degree of A. B. and is a teacher of English in the Armstrong High School of Washington, D. C.

You start out after you have gone from kindergarten to sheepskin covered with sundry Latin phrases.

At least you know what you want life to give you. A career as fixed and as calmly brilliant as the North Star. The one real thing that money buys. Time. Time to do things. A house that can be as delectably out of order and as easily put in order as the doll-house of “playing-house” days. And of course, a husband you can look up to without looking down on yourself.

Somehow you feel like a kitten in a sunny catnip field that sees sleek, plump brown field mice and yellow baby chicks sitting coyly, side by side, under each leaf. A desire to dash three or four ways seizes you.

That’s Youth.

But you know that things learned need testing — acid testing — to see if they are really after all, an interwoven part of you. All your life you have heard of the debt you owe “Your People” because you have managed to have the things they have not largely had.

So you find a spot where there are hordes of them — of course below the Line — to be your catnip field while you close our eyes to mice and chickens alike.

If you have never lived among your own, you feel prodigal. Some warm untouched current flows through them — through you — and drags you out into the deep waters of a new sea of human foibles and mannerisms; of a peculiar psychology and prejudices. And one day you find yourself entangled — enmeshed — pinioned in the seaweed of a Black Ghetto.

Not a Ghetto, placid like the Strasse that flows, outwardly unperturbed and calm in a stream of religious belief, but a peculiar group. Cut off, flung together, shoved aside in a bundle because of color and with no more in common.

Unless color is, after all, the real bond.

Milling around like live fish in a basket. Those at the bottom crushed into a sort of stupid apathy by the weight of those on top. Those on top leaping, leaping; leaping to scale the sides; to get out.

There are two “colored” movies, innumerable parties — and cards. Cards played so intensely that it fascinates and repulses at once.

Movies.

Movies worthy and worthless — but not even a low-caste spoken stage.

Parties, plentiful. Music and dancing and much that is wit and color and gaiety.

[end of page]

Marita Bonner’s 1925 essay “On Being Young, a Woman — and Colored,” won first prize from the NAACP’s magazine The Crisis in 1925. The Crisis vol. 31, no. 2. Dec. 1925/Public Domain

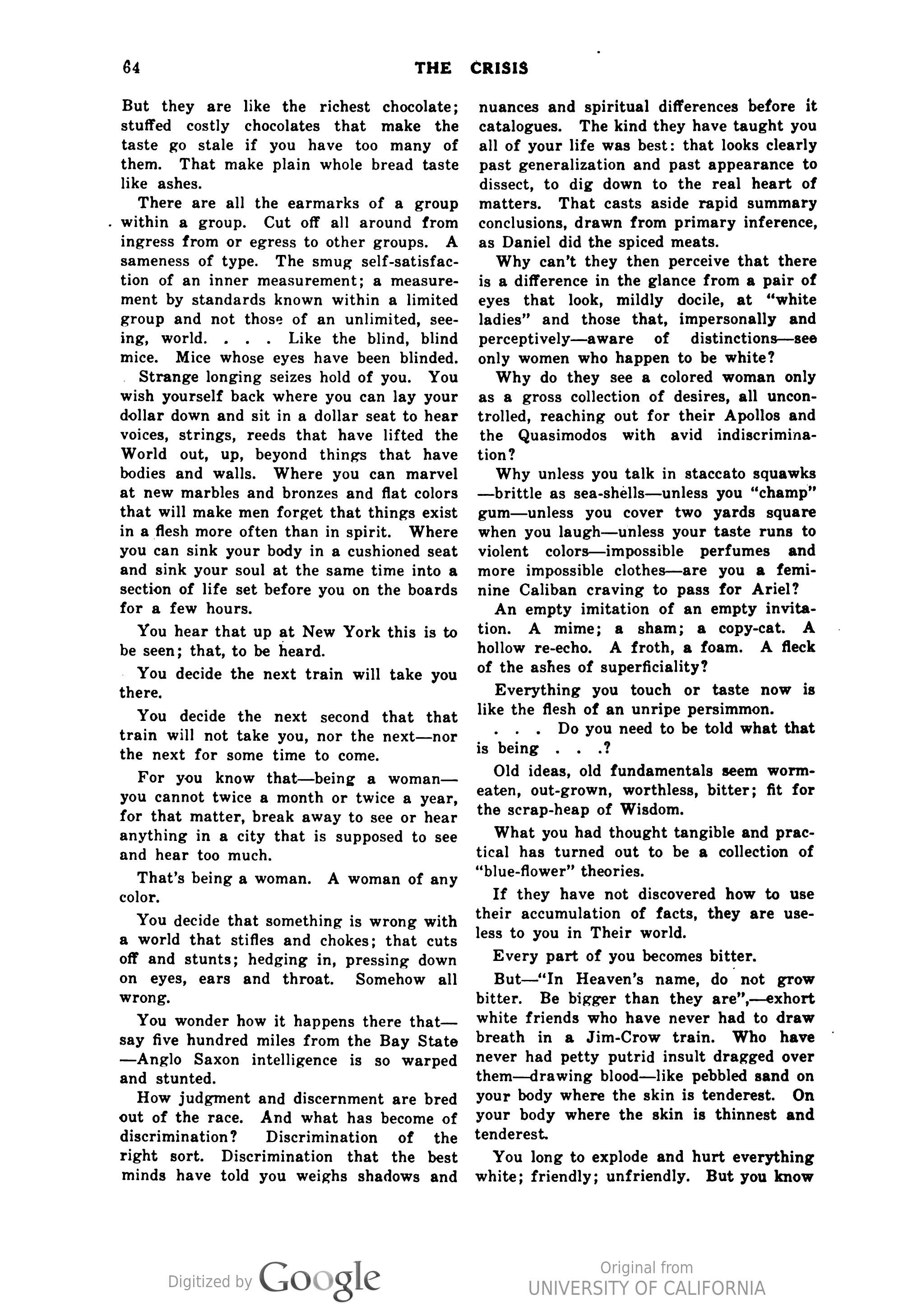

Open and scroll to read the essay transcript

[page header] THE CRISIS

But they are like the richest chocolate; stuffed costly chocolates that make the taste go stale if you have too many of them. That make plain whole bread taste like ashes.

There are all the earmarks of a group within a group. Cut off all around from ingress from or egress to other groups. A sameness of type. The smug self-satisfaction of an inner measurement; a measurement by standards known within a limited group and not those of an unlimited, seeing, world. … Like the blind, blind mice. Mice whose eyes have been blinded.

Strange longing seizes hold of you. You wish yourself back where you can lay your dollar down and sit in a dollar seat to hear voices, strings, reeds that have lifted the World out, up, beyond things that have bodies and walls. Where you can marvel at new marbles and bronzes and flat colors that will make men forget that things exist in a flesh more often than in spirit. Where you can sink your body in a cushioned seat and sink your soul at the same time into a section of life set before you on the boards for a few hours.

You hear that up at New York this is to be seen; that, to be heard.

You decide the next train will take you there.

You decide the next second that that train will not take you, nor the next — nor the next for some time to come.

For you know that — being a woman — you cannot twice a month or twice a year, for that matter, break away to see or hear anything in a city that is supposed to see and hear too much.

That’s being a woman. A woman of any color.

You decide that something is wrong with a world that stifles and chokes; that cuts off and stunts; hedging in, pressing down on eyes, ears and throat. Somehow all wrong.

You wonder how it happens there that — say five hundred miles from the Bay State — Anglo Saxon intelligence is so warped and stunted.

How judgment and discernment are bred out of the race. And what has become of discrimination? Discrimination of the right sort. Discrimination that the best minds have told you weighs shadows and nuances and spiritual differences before it catalogues. The kind thy have taught you all of your life was best: that looks clearly past generalization and past appearance to dissect, to dig down to the real heart of matters. That casts aside rapid summary conclusions drawn from primary inference, as Daniel did the spiced meats.

Why can’t they then perceive that there is a difference in the glance from a pair of eyes that look, mildly docile, at “white ladies” and those that, personally and perceptively — aware of distinctions — see only women who happen to be white?

Why do they see a colored woman only as a gross collection of desires, all uncontrolled, reaching out for their Apollos and the Quasimodos with avid indiscrimination?

Why unless you talk in staccato squawks — brittle as sea-shells — unless you “champ” gum — unless you cover two yards square when you laugh — unless your taste runs to violent colors — impossible perfumes and more impossible clothes — are you a feminine Caliban craving to pass for Ariel?

An empty imitation of an empty invitation. A mime; a sham; a copy-cat. A hollow re-echo. A froth, a foam. A fleck of the ashes of superficiality?

Everything you touch or taste now is like the flesh of an unripe persimmon.

…Do you need to be told what that is being…?

Old ideas, old fundamentals seem worm-eaten, out-grown, worthless, bitter; fit for the scrap-heat of Wisdom.

What you had thought tangible and practical has turned out to be a collection of “blue-flower” theories.

If they have not discovered how to use their accumulation of facts, they are useless to you in Their world.

Every part of you becomes bitter.

But — “In Heaven’s name, do not grow bitter. Be bigger than they are”,–exhort white friends who have never had to draw breath in a Jim-Crow train. Who have never had petty putrid insult dragged over them — drawing blood — like pebbled sand on your body where the skin is tenderest. On your body where the skin is thinnest and tenderest.

You long to explode and hurt everything white; friendly; unfriendly. But you know

[end of page]

Bonner’s powerful essay highlighted the harsh realities young women face as a result of discrimination — especially when they are Black. “On Being Young, A Woman — and Colored,” The Crisis vol. 31, no. 2. Dec. 1925./Public Domain

Open and scroll to read the essay transcript

[page header] DECEMBER, 1925

That you cannot live with a chip on your shoulder even if you can manage a smile around your eyes — without getting steely and brittle and losing the softness that makes you a woman.

For chips make you bend your body to balance them. And once you bend, you lose your poise, your balance, and the chip gets into you. The real you. You get hard.

…And many things in you can ossify…

And you know, being a woman, you have to go about it gently and quietly, to find out and to discover just what is wrong. Just what can be done.

You see clearly that they have acquired things.

Money; money. Money to build with, money to destroy. Money to swim in. Money to drown in. Money.

An ascendancy of wisdom. An incalculable hoard of wisdom in all fields, in all things collected from all quarters of humanity.

A stupendous mass of things.

Things.

So, too, the Greeks … Things.

And the Romans. …

And you wonder and wonder why they have not discovered how to handle deftly and skillfully, Wisdom, stored up for them — like the honey for the Gods on Olympus — since time unknown.

You wonder and you wonder until you wander out into Infinity, where — if it is to be found anywhere — Truth really exists.

The Greeks had possessions, culture. They were lost because they did not understand.

The Romans owned more than anyone else. Trampled under the heel of Vandals and Civilization, because they would not understand.

Greeks. Did not understand.

Romans. Would not understand.

“They.” Will not understand.

So you find, they have shut Wisdom up and have forgotten to find the key that will let her out. They have trapped, trammeled, lashed her to themselves with thews and thongs and theories. They have ransacked sea and earth and air to bring every treasure to her. But she sulks and will not work for a world with a whitish hue because it has snubbed her twin sister, Understanding.

You see clearly — off there is Infinity — Understanding. Standing alone, waiting for someone to really want her.

But she is so far out there is no way to snatch at her and drag her in.

So — being a woman — you can wait.

You must sit quietly without a chip. Not sodden — and weighted as if you feet were cast in the iron of your soul. Not wasting strength in enervating gestures as if two hundred years of bonds and whips had really tricked you into nervous uncertainty.

But quiet; quiet. Like Buddha — who brown like I am — sat entirely at ease, entirely sure of himself; motionless and knowing, a thousand years before the white man knew there was so very much difference between feet and hands.

Motionless on the outside. But inside?

Silent.

Still… “Perhaps Buddha is a woman.”

So you too. Still; quiet; with a smile, ever so slight, at the eyes so that Life will flow into and not by you. And you can gather, as it passes, the essences, the overtones, the tints, the shadows; draw understanding to your self.

And then you can, when Time is ripe, swoop to your feet — at your full height — at a single gesture.

Ready to go where?

Why… Wherever God motions.

[beginning of following story, “Cantabile,” by Effie Lee Newsome]

[end of page; end of story]

Bonner’s essay did not shy away from uncomfortable truths. Despite the guidance of one white professor at Radcliffe “to write — but not to be bitter”, she delivered a blunt assessment of the prejudices that constrained Black women. “On Being Young, A Woman — and Colored,” The Crisis vol. 31, no. 2. Dec. 1925/Public Domain

Music also continued to be a part of her creative portfolio, and in 1927 Bonner won the Wanamaker Music Contest for Black composers.

As a participant in the Harlem Renaissance, she engaged with celebrated writers such as poet Langston Hughes, philosopher Alain Locke (A.B. 1907, Ph.D. 1918), and novelist, poet, and editor Jessie Redmond Faucet at the S Street salon in Washington, DC, hosted by poet and playwright Georgia Douglass Johnson.

Open and scroll to read the notebook transcript

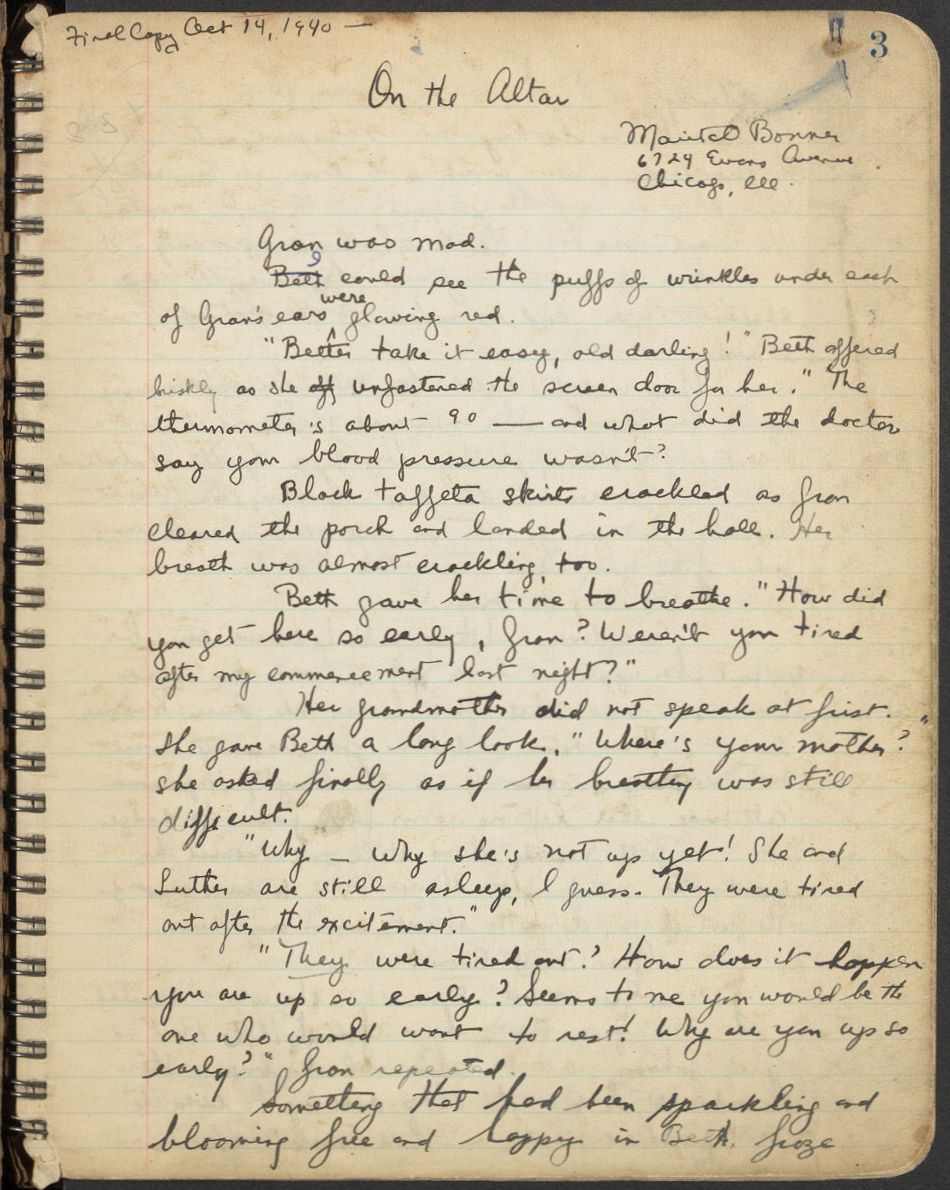

Final Copy Oct 14, 1940 —

On the Altar

Marita O Bonner

6724 Evans Avenue

Chicago, Ill.

Gran was mad.

Beth I could see the puffs of wrinkles under each of Gran’s ears ^were glowing red.

“Better take it easy, old darling!” Beth offered briskly as she off unfastened the screen door for her. “The thermometer’s about 90 — and what did the doctor say your blood pressure wasn’t?

Black taffeta skirts crackled as Gran cleared the porch and landed in the hall. Her breath was almost cracking, too.

Beth gave her time to breathe. “How did you get here so early, Gran? Weren’t you tired after my commencement last night?”

Her grandmother did not speak at first. She gave Beth a long look. “Where’s your mother?” she asked finally as if her breathing was still difficult.

“Why — Why she’s not up yet! She and Luther are still asleep, I guess. They were tired out after the excitement.”

“They were tired out? How does it happen you are up so early? Seems to me you would be the one would want to rest! Why are you up so early?” Gran repeated.

Something that had been sparkling and blooming free and happy in Beth froze

[end of page]

Bonner returned to teaching in 1941 and gave up writing. Handwritten draft of short story “On the Altar.” Dated October 14, 1940. Notebook of stories, published and unpublished, 1940. Marita Bonner Papers, 1940–1986. SC 97, folder 4. Radcliffe College Archives/Schlesinger Library

Open and scroll to read the notebook transcript

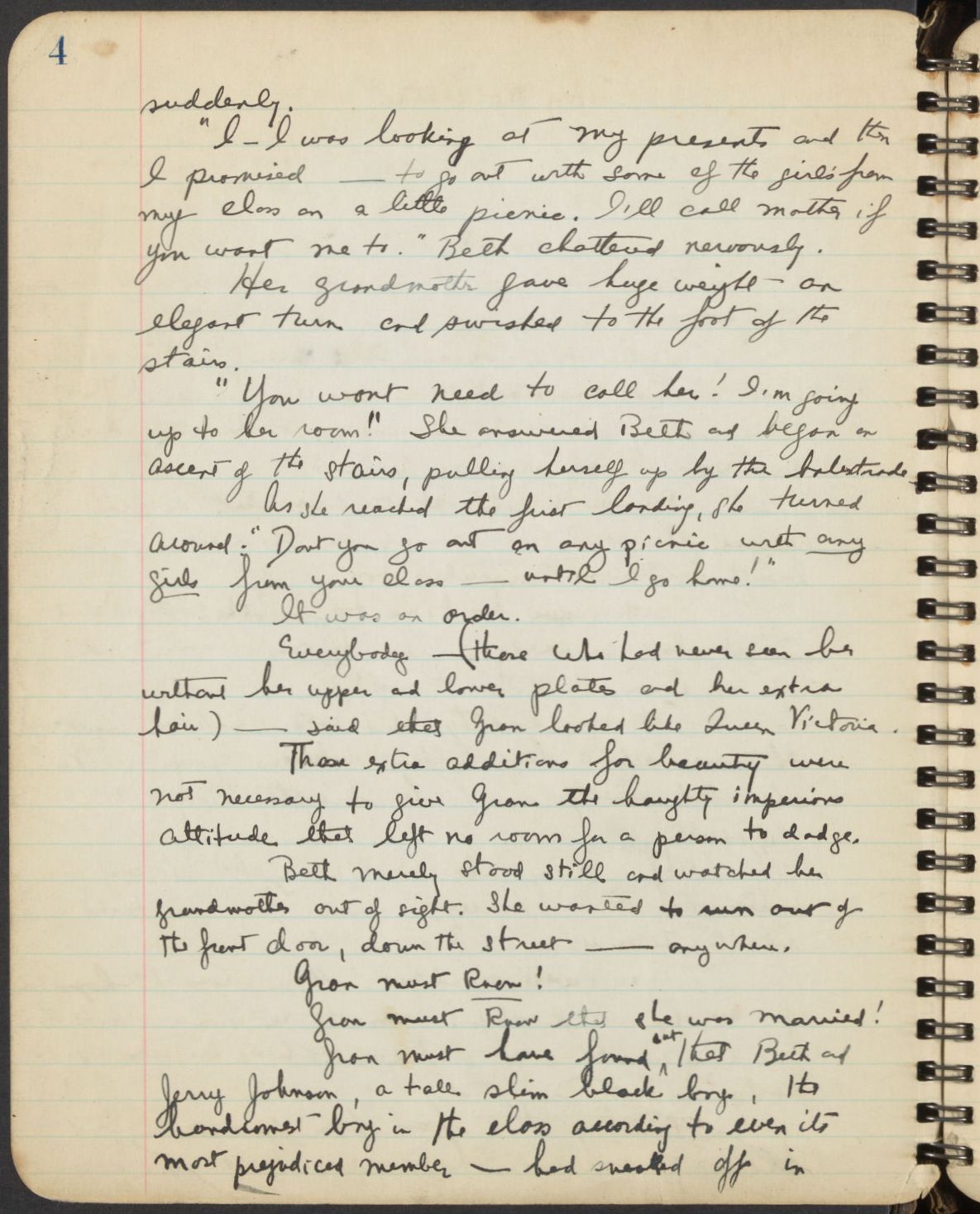

suddenly.

“I_I was looking at my presents and then I promised __ to go out with some of the girls from my class on a little picnic. I’ll call mother if you want me to.” Beth chattered nervously.

Her grandmothr gave huge weight an elegant turn and swished to the foot of the stairs.

“You wont need to call her! I’m going up to her room.” She answered Beth and began an ascent of the stairs, pulling herself up by the balustrade.

As she reached the first landing, she turned around. “Dont you go out on any picnic with [next two words underlined] any girls from your class __ until I go home!” It was an order.

Everybody __(those who had never seen her without her upper and lower plates and her extra hair) __ said that Gran looked like Queen Victoria.

Those extra additions for beauty were not necessary to give Gran the haughty imperious attitude that left no room for a person to dodge.

Beth merely stood still and watched her grandmother out of sight. She wanted to run out of the front door, down the street __ anywhere.

Gran must [underlined] know!

Gran must know that she was married!

Gran must have found ^out that Beth and Jerry Johnson, a tall slim black boy, the handsomest boy in the class according to even its most prejudiced member __ had sneaked off in

[end of page]

At the time of her death her work had not received wide recognition, but her essays, plays, and stories remain powerful and all too familiar. Handwritten draft of short story “On the Altar.” Dated October 14, 1940. Notebook of stories, published and unpublished, 1940. Marita Bonner Papers, 1940–1986. SC 97, folder 4. Radcliffe College Archives/Schlesinger Library

Open and scroll to read the notebook transcript

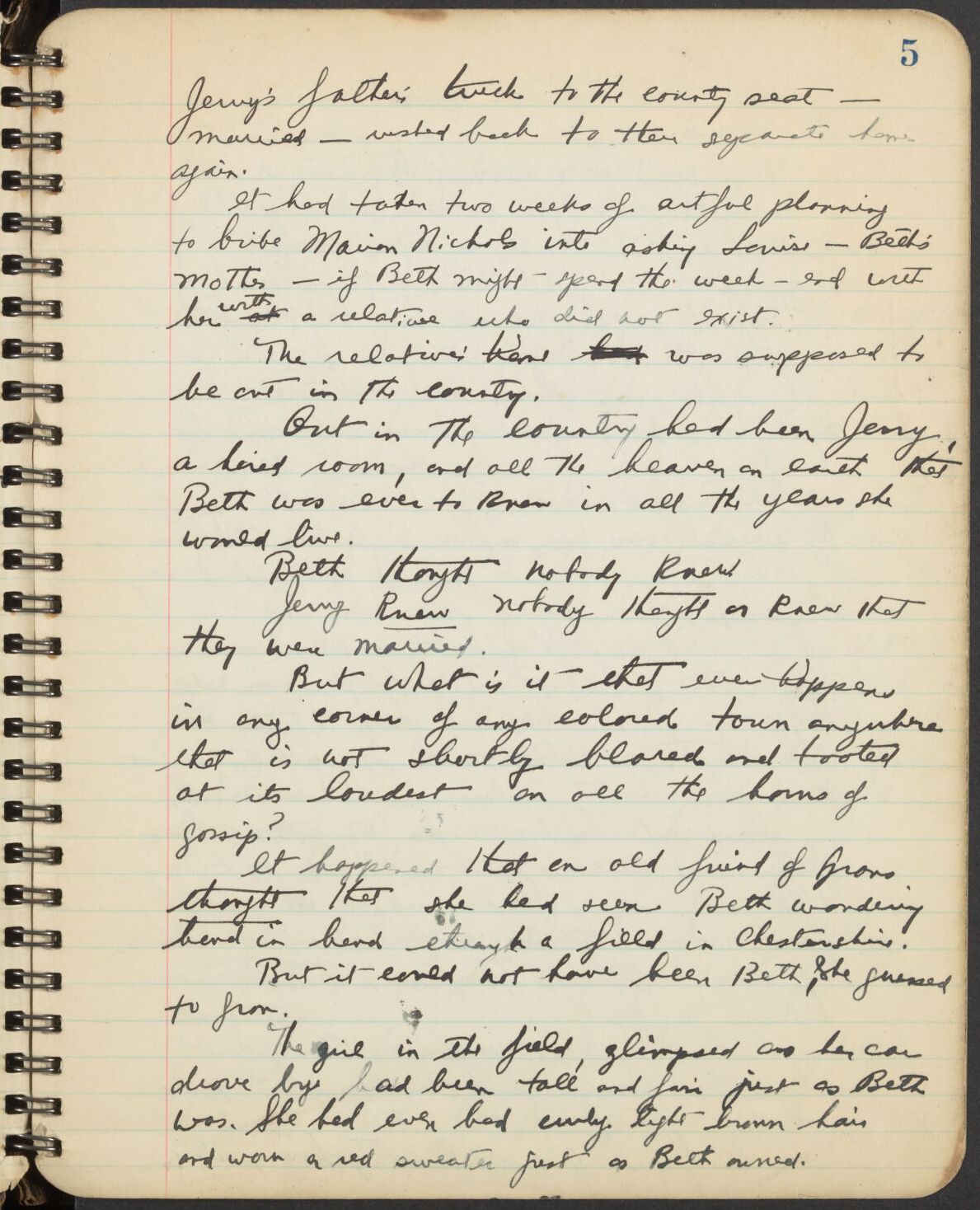

Jerry’s father’s truck to the county seat — married __ rushed back to their separate homes again.

It had taken two weeks of artful planning to bribe Marion Nichols into asking Louise — Beth’s mother — if Beth might spend the week-end with her with [crossed out] at a relative who did not exist.

The relative’s home [scribbled out] had was supposed to be out in the country.

“You wont need to call her! I’m going up to her room.” She answered Beth and began an ascent of the stairs, pulling herself up by the balustrade.

Out in the country had been Jerry, a hired room, and all the heaven on earth that Beth was ever to know in all the years she would live.

Beth thought nobody knew.

Jerry[underlined] knew nobody thought or knew that they were married.

But what is it that ever happens in any corner of any colored town anywhere that is not shortly blared and tooted at its loudest on all the horns of gossip?

It happened that an old friend of Grans [underlined] thought that she had seen Beth wandering hand in hand through a field in Chestershire.

But it could not have been Beth, she guessed to Gran.

The girl in the field, glimpsed as her car drove by had been tall and fair just as Beth was. She had even had curly light brown hair and worn a red sweater just as Beth owned. […]

[end of page; end of notebook transcript]

Handwritten draft of short story “On the Altar.” Dated October 14, 1940. Notebook of stories, published and unpublished, 1940. Marita Bonner Papers, 1940–1986. SC 97, folder 4. Radcliffe College Archives/Schlesinger Library

A Lasting Legacy

In 1941, Bonner returned to teaching and stopped writing to spend more time with her husband and three children. Living in Chicago at the time, she taught at the predominantly Black Phillips High School from 1944 to 1949 and at the Doolittle School from 1950 to 1963.

Bonner died in 1971. At the time of her death her work had not received wide recognition, but her essays, plays, and stories remain powerful and their themes all too familiar. A collection of her writings, Frye Street & Environs: The Collected Works of Marita Bonner, was published to acclaim in 1986. A review in the New York Times called it “a life work of significance,” and Publisher’s Weekly noted that Bonner’s “Depression-era characters exude an air of universality that makes them pungently relevant for our times.”

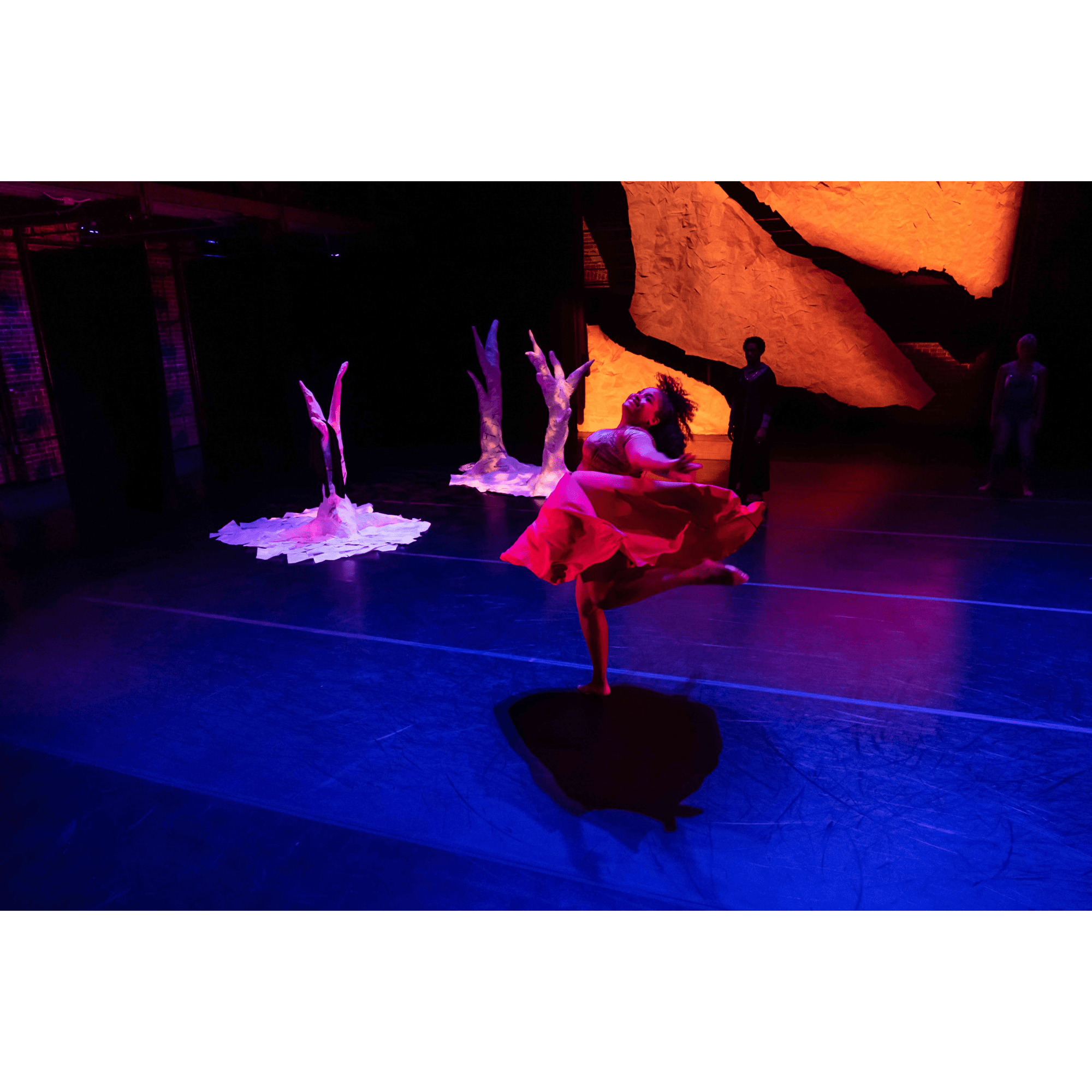

In 2021, playwright NaTasha Thompson revitalized Bonner’s prize-winning play “The Purple Flower.” Her adaptation Lavender Terrace, which premiered at the New Hazlett Theater in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, brings Bonner’s artistry to 21st century audiences, demonstrating how her ideas continue to speak to the Black experience today.

NaTasha Thompson, playwright. Lavender Terrace. New Hazlett Theater, Pittsburgh, PA: 2021/Courtesy of NaTasha Thompson [click here for an extended clip of the performance]

Selected Sources

Bonner, Marita, Joyce Flynn and Joyce Occomy Stricklin. Frye Street & Environs: The Collected Works of Marita Bonner. Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1998.

“Marita O. Bonner,” in Blacks at Harvard: A Documentary History of African-American Experience At Harvard and Radcliffe, ed. Werner Sollors et al. (New York, NY: NYU Press, 1993), 229–234.

Interview with Gale and William Occomy re: their mother Marita Bonner Occomy. Side 1. Radcliffe College Archives sound recordings collection, 1951-2008, RG XX, Series 8-9, 87-T11. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute.

Marita Bonner Papers, 1940-1986. SC 97, folder #. Radcliffe College Archives, Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

Roses, Lorraine Elena, and Ruth Elizabeth Randolph. “Marita Bonner: In Search of Other Mothers’ Gardens.” Black American Literature Forum 21, no. 1/2 (1987): 165–83.

More profiles

Alberta Virginia Scott

Alberta Virginia Scott created a quietly powerful legacy as the first Black woman to graduate from Radcliffe College.

Caroline Bond Day

Caroline Bond Day earned her A.M. in anthropology in 1930, making her one of the first African Americans to earn a graduate degree from Radcliffe College. Her work in anthropology directly challenged the racial hierarchies…

Frances O. Grant

Frances O. Grant, the first Black woman elected to the Iota Chapter of Phi Beta Kappa, graduated from Radcliffe College in 1917. She went on to an extraordinary career as an educator, primarily at the…