Eva B. Dykes

Class of 1921

Eva B. Dykes

Eva Beatrice Dykes made history at Radcliffe College in 1921 as the first Black woman to complete the requirements for a Ph.D. in the United States.

School: Radcliffe College

Degree: A.B., A.M., Ph.D.

Area of Impact: Education, Arts

HBCU Affiliation: Oakwood University, Howard University, Walden University

Radcliffe College: Becoming a First

Eva Beatrice Dykes, a Washington, DC, native, was not new to the world of scholarship when she arrived at Radcliffe College. She was part of the second generation of her family to attend Howard University — her father, three uncles, and sister were all graduates of the eminent historically Black institution. Dykes’s mother also studied at Howard until illness forced her to withdraw.

Dykes earned her bachelor’s degree from Howard University, summa cum laude, in 1914.

Many of the images in this profile appear here courtesy of the Oakwood University Archives at the Eva B. Dykes Library.

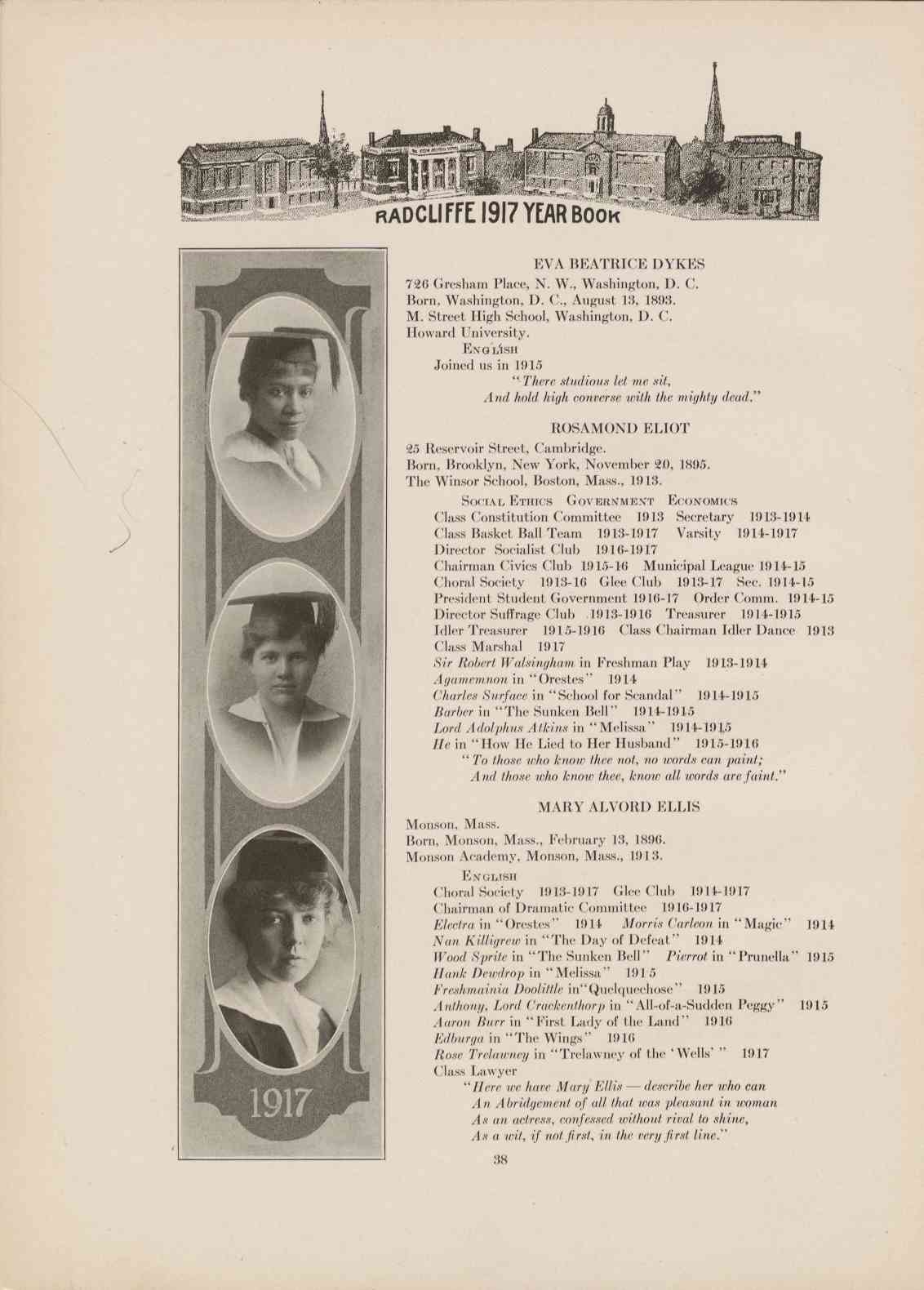

Following a year spent teaching English and Latin at Walden University, a historically Black college in Nashville, Tennessee, she applied to Radcliffe to pursue a master’s degree. Because of limited resources and racist policies, Howard and other historically Black colleges and universities were not nationally accredited at that time. So, like many early Black students who entered Harvard and Radcliffe, Dykes was forced to enroll as an undergraduate and earn a second bachelor’s degree before she was allowed to begin her graduate studies.

Dykes explained in an interview for the Black Women Oral History Project, conducted with support from the Schlesinger Library at Radcliffe in the 1970s, “the registrar wrote back and said I would have to attend Radcliffe so that they could determine what type of work I would do. So my uncle decided to have me go there as an unclassified student, and also get another A.B. from a school that was accredited at that time. That’s what I did. I went to Radcliffe as an unclassified student, and after I had been there one year, then I was classified as a senior.”

In 1917, she earned a Radcliffe A.B., magna cum laude, with concentrations in English, Latin, German, and Greek, and completed her A.M. in 1918.

Open and scroll to read the diploma transcript

[visibly aged and badly water-stained]

[printed in a curved arch at the top of the page]

Procuratores

[remaining text printed in horizontal lines]

UNIVERSITATIS HOWARDIANAE

IN

Agro Columbiae

Omnibus has literas perlecturis salute in Domino sempiternam.

Vobis notum sit quod Dominum [name handwritten] Eva Beatrice Dykes juvenem studiis doctrinae colendis cognitum. PROCURATORES commendatibus PROFESORIBUS HONORANDES titulo graduques [degree and honors handwritten] Artium Baccalaurei summa cum laude adornareiunt et condecoraveiunt et ei fruenda contuleiunt omnia et singular jura, privilegia, honores, dignitates, insignia, quae hic aut uspiam gentium ad cunde in gradum [handwritten] Artium evectis concede solent.

Cujus rei publicum UNIVERSITATIS sigillum ei Praesidis autographum literis hisce affixa, testimonio sint___________________

anno salutis millisimo nongentisimi [handwritten] quarto decimo annoque Universitatis [handwritten] quadragesimo septimo,

[left: handwritten signature] GeorgeWCook [pre-printed] Secretarius

[right: handwritten signature] S.M. Newman [pre-printed] Praeses

[end of document]

Dykes was part of the second generation of her family to attend Howard University. Alvin Goulbourne, photographer. “Eva B. Dykes’ Howard University degree”/Courtesy of Oakwood University Archives

Open and scroll to read the diploma transcript

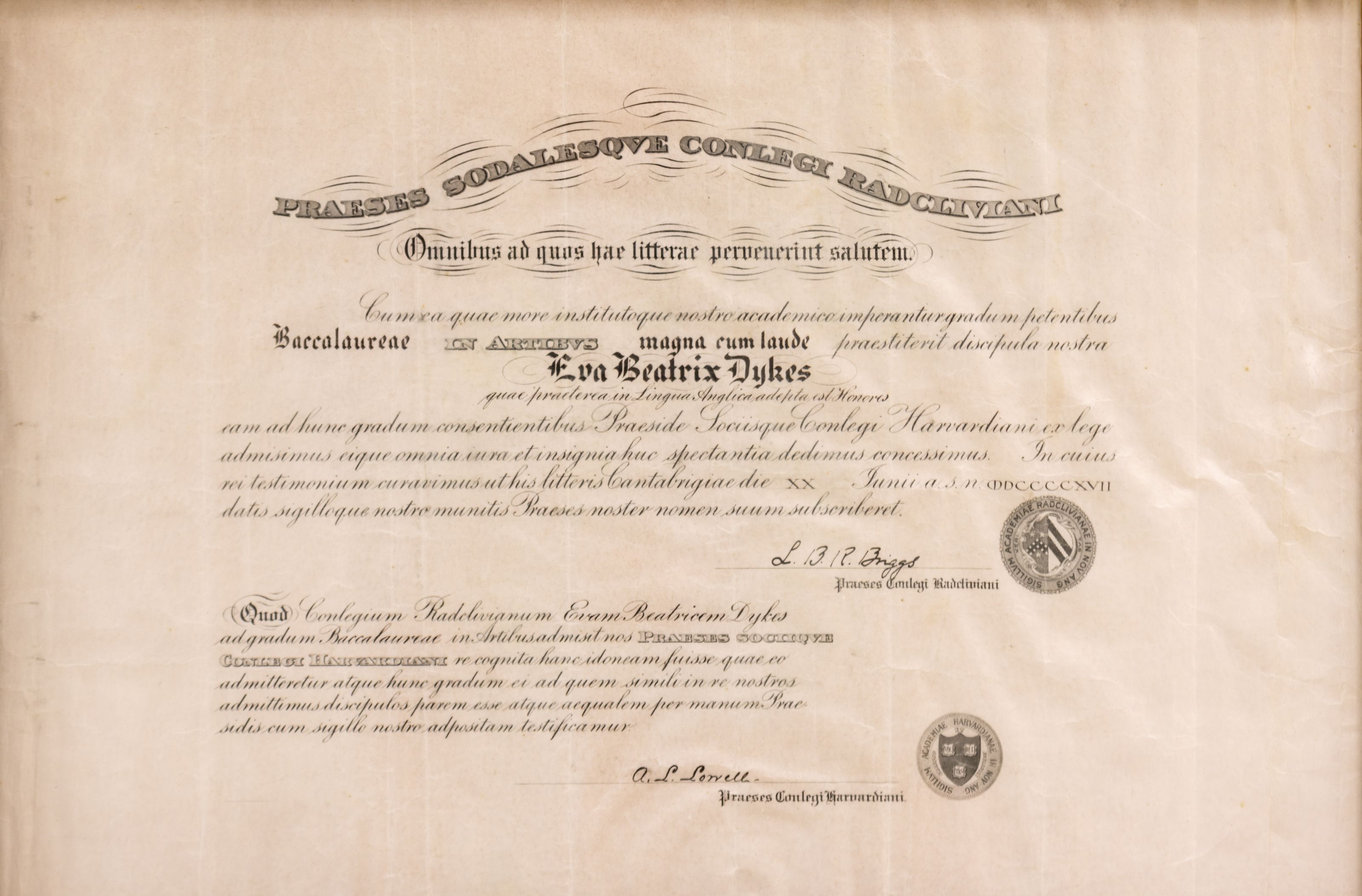

[printed in a curved arch at the top of the page]

PRAESES SODALESQUE CONLEGI RADCLIVIANI

[remaining text printed in horizontal lines]

Omnibus ad quos hae litterae pervenerint salutem.

Cum ea quae more institutoque nostro academico imperanturgradum petentibus [handwritten] Baccalaureae [pre-printed] IN ARTIBUS [handwritten] magna cum laude [pre-printed] praestiterit discipula nostra

[handwritten] Eva Beatrix Dykes

[handwritten] quae praeterea in Lingua Anglica adepta est Honores

[pre-printed] eam ad hunc gradum consentientibus Praeside Sociisque Conlegi Harvardiani ex lege admisimus eique omnia iura et insignia huc spectantia dedimus concessimus. In cuius rei testimonium curavimus ut his litteris Cantabrigiae die XX Junii a. s. n. DDCCCCXVII datis sigilloque nostro munitis Praeses noster nomen suum subscriberet.

[handwritten signature] L. B. R. Briggs

Praeses Conlegi Radcliviani

[to the right of the signature: round official seal with Radcliffe shield encircled by the words “SIGILLUM ACADEMIAE RADCLIVIANAE IN NOV ANG”]

Quod Conlegium Radclivianum [handwritten] Evam Beatricem Dykes

[pre-printed] ad gradum [handwritten] Baccalureae [pre-printed] in Artibus admisit nos PRAESES SOCIIQUE CONLEGI HARVARDIANI re cognita hanc idoneam fuisse quae eo admitteretur atque hunc gradum ei ad quem simili in re nostros admittimus discipulos parem esse atque aequalem per manum Praesidis cum sigillo nostro adpositam testificamur.

[handwritten signature] A. L. Lowell.

Praeses Conlegi Harvardiani.

[to the right of the signature: round official seal with Harvard shield encircled by the words “SIGILLUM ACADEMIAE HARVARDIANAE IN NOV ANG”]

[end of document]

Because of limited resources and racist policies, historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) were not nationally accredited before 1956. Like many early Black students of Harvard and Radcliffe, Dykes was forced to earn a bachelor’s degree from Radcliffe before pursuing graduate studies. Alvin Goulbourne, photographer. “Eva B. Dykes’ Radcliffe College bachelor’s degree.” 1917/Courtesy of Oakwood University Archives

Open and scroll to read the diploma transcript

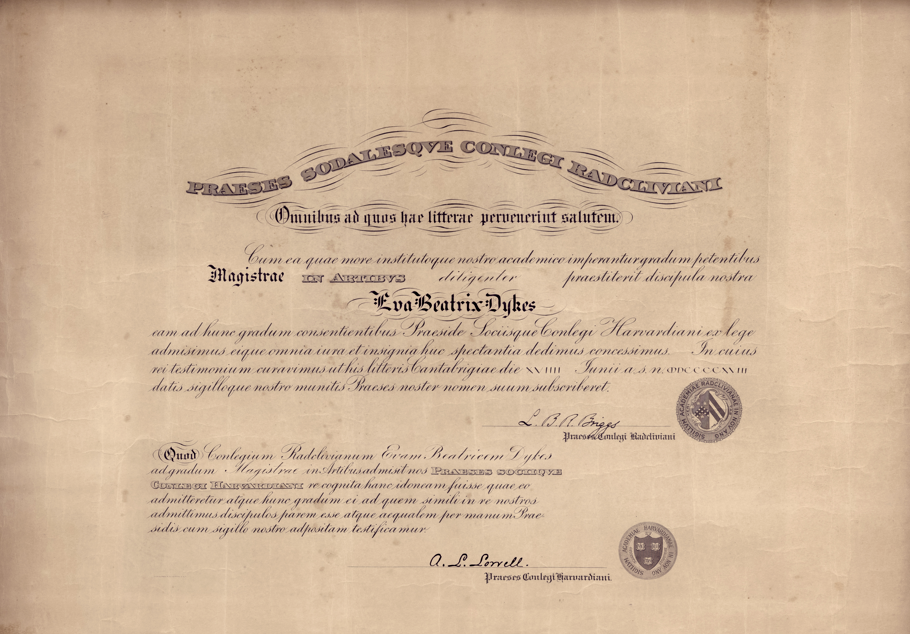

[printed in a curved arch at the top of the page]

PRAESES SODALESQUE CONLEGI RADCLIVIANI

[remaining text printed in horizontal lines]

Omnibus ad quos hae litterae pervenerint salutem.

Cum ea quae more institutoque nostro academico imperanturgradum petentibus [handwritten] Magistrae [pre-printed] IN ARTIBUS [handwritten] diligenter [pre-printed] praestiterit discipula nostra

[handwritten] Eva Beatrix Dykes

[pre-printed] eam ad hunc gradum consentientibus Praeside Sociisque Conlegi Harvardiani ex lege admisimus eique omnia iura et insignia huc spectantia dedimus concessimus. In cuius rei testimonium curavimus ut his litteris Cantabrigiae die XVIIII Junii a. s. n. DDCCCCXVIII datis sigilloque nostro munitis Praeses noster nomen suum subscriberet.

[handwritten signature] L. B. R. Briggs

Praeses Conlegi Radcliviani

[to the right of the signature: round official seal with Radcliffe shield encircled by the words “SIGILLUM ACADEMIAERADCLIVIANAE IN NOV ANG”]

Quod Conlegium Radclivianum [handwritten] Evam Beatricem Dykes

[pre-printed] ad gradum [handwritten] Magistrae [pre-printed] in Artibus admisit nos PRAESES SOCIIQUECONLEGI HARVARDIANI re cognita hanc idoneam fuisse quae eo admitteretur atque hunc gradum ei ad quem simili in re nostros admittimus discipulos parem esse atque aequalem per manum Praesidis cum sigillo nostro adpositam testificamur.

[handwritten signature] A. L. Lowell.

Praeses Conlegi Harvardiani.

[to the right of the signature: round official seal with Harvard shield encircled by the words “SIGILLUM ACADEMIAE HARVARDIANAE IN NOV ANG”]

[end of document]

Dykes earned her Radcliffe A.B., magna cum laude, in 1917 with concentrations in English, Latin, German, and Greek. She completed her A.M. just a year later in 1918. Alvin Goulbourne, photographer. “Eva B. Dykes’ Radcliffe College master’s degree.” 1918. Eva B. Dykes Collection/Courtesy of Oakwood University Archives

While Dykes almost certainly experienced discrimination and isolation, her Cambridge years also provided a welcome respite from the more pervasive racism and Jim Crow segregation she faced at home in the South. In the same oral history interview, Dykes described how segregation forced her to conduct her doctoral research only in northern states, including at historical societies in Pennsylvania and Massachusetts.

My teacher wanted me to go to North Carolina, but I couldn’t go, because I was black. So I couldn’t attend the historical society there. But on the other hand, I was able to get through without meeting prejudice […].

In 1921, Dykes completed her dissertation — on the English poet Alexander Pope — and became the first Black woman to complete the requirements for the Ph.D. in the United States. Because of the date of Harvard’s commencement, Dykes was the third Black woman to graduate with the Ph.D. degree that year.

When asked to discuss her achievement later in life in her oral history interview, she steadfastly refused to call herself the first. Instead, she focused on the fact that she was one of the first three Black women to earn the Ph.D. in 1921, naming Sadie Mossell Alexander at the University of Pennsylvania and Georgiana Simpson at the University of Chicago as the others.

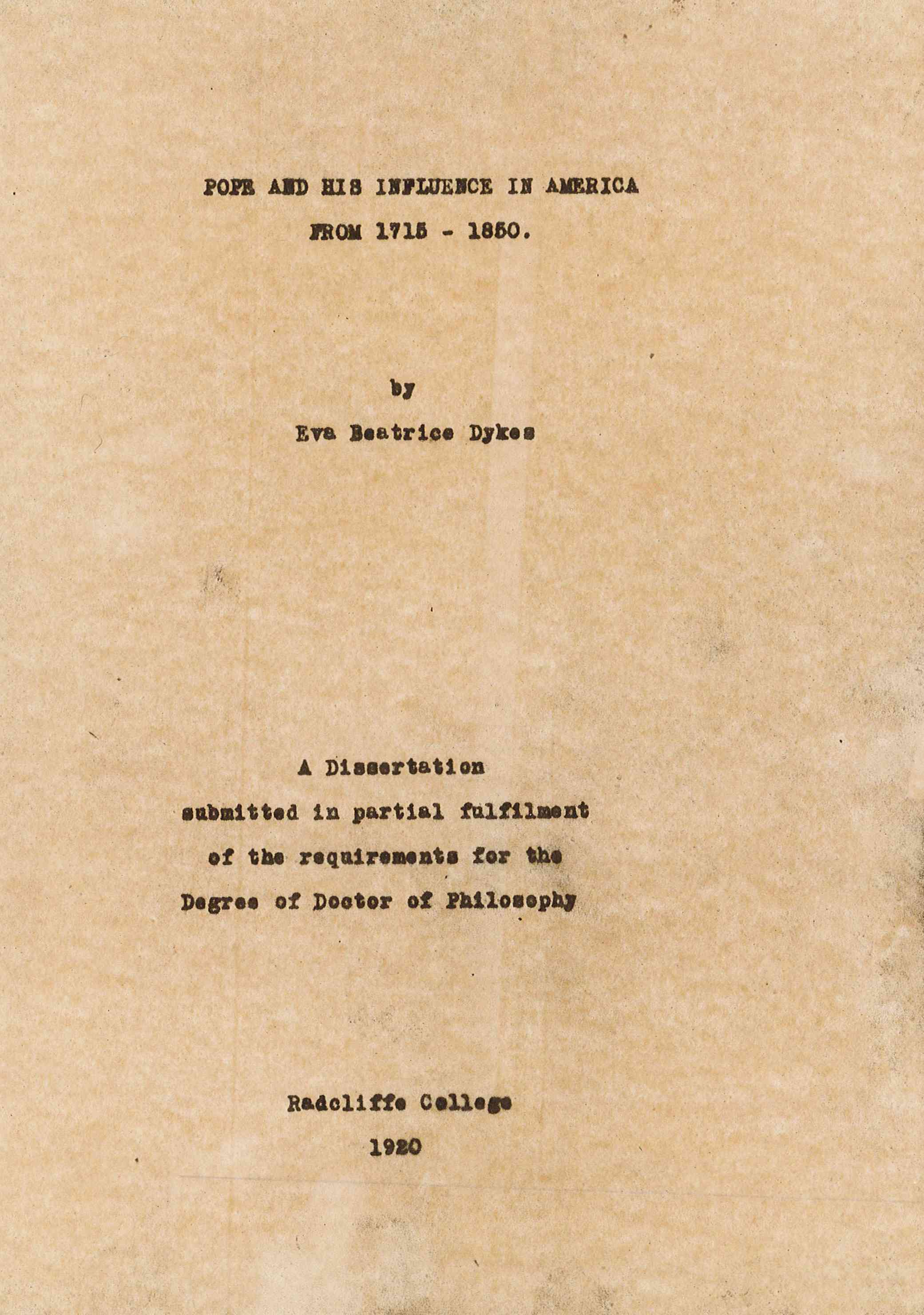

Open and scroll to read the dissertation transcript

[all text centered on the page]

POPE AND HIS INFLUENCE IN AMERICA

FROM 1715 – 1850.

by

Eva Beatrice Dykes

A Dissertation

submitted in partial fulfilment

of the requirements for the

Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

Radcliffe College

1920

[end of page]

When Dykes completed her dissertation in 1921, she became the first Black woman to complete the requirements for the Ph.D. Eva B. Dykes. Title page of “Pope and His Influence in America from 1715–1850.” Ph.D. dissertation. Radcliffe College, 1921/Courtesy of Oakwood University Archives

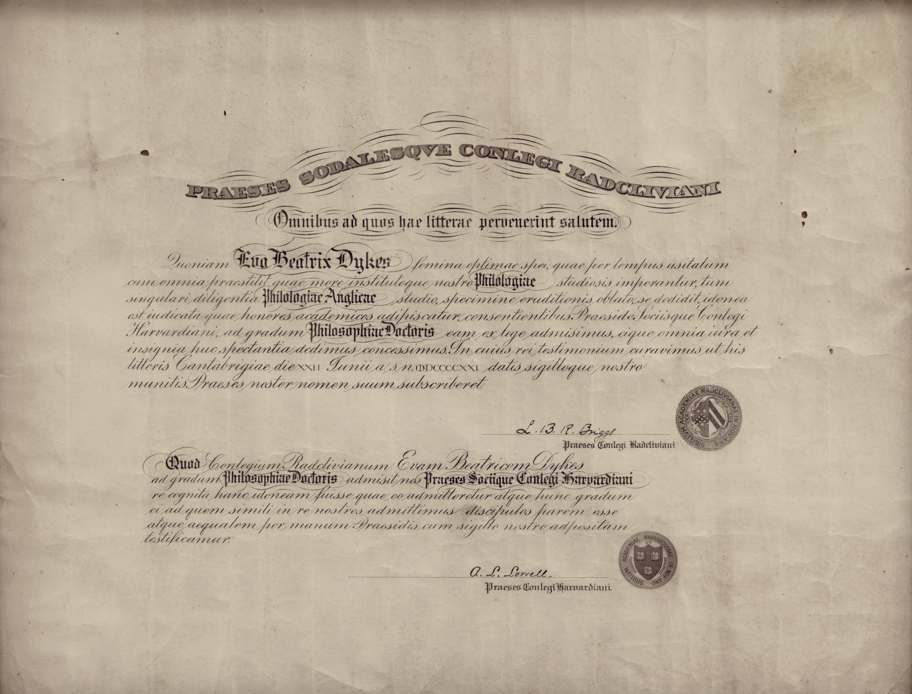

Open and scroll to read the diploma transcript

[printed in a curved arch at the top of the page]

PRAESES SODALESQUE CONLEGI RADCLIVIANI

[remaining text printed in horizontal lines]

Omnibus ad quos hae litterae pervenerint salutem.

Quoniam Eva Beatrix Dykes [pre-printed] femina optimae spei, quae per tempus usitatum cum omnia praestitit quae more institutoque nostro [handwritten] Philologiae [pre-printed] studiosis imperantur, tum singulari diligentia [handwritten] Philologiae Anglicae [pre-printed] studio, specimine eruditionis oblate, se dedidit idonea est indicate quae honores academicos adipiscatur, consentientibus Praeside Sciisque Conlegi Harvariani ad gradum [handwritten] Philosophiae Doctoris [pre-printed] eam ex lege admisimus, eique omnia iura et insignia huc spectantia dedimus concessimus. In cuius rei testimonium curavimus ut his litteris Cantabrigiae die XXII Junii a. s. n. DDCCCCXXI datis sigilloque nostro munitis Praeses noster nomen suum subscriberet.

[handwritten signature] L. B. R. Briggs

Praeses Conlegi Radcliviani

[to the right of the signature: round official seal with Radcliffe shield encircled by the words “SIGILLUM ACADEMIAE RADCLIVIANAE IN NOV ANG”]

Quod Conlegium Radclivianum [handwritten] Evam Beatricem Dykes

[pre-printed] ad gradum [handwritten] Philosophiae Doctoris [pre-printed] admisit nos [handwritten] PRAESES SOCIIQUE CONLEGI HARVARDIANI re cognita hanc idoneam fuisse quae eo admitteretur atque hunc gradum ei ad quem simili in re nostros admittimus discipulos parem esse atque aequalem per manum Praesidis cum sigillo nostro adpositam testificamur.

[handwritten signature] A. L. Lowell.

Praeses Conlegi Harvardiani.

[to the right of the signature: round official seal with Harvard shield encircled by the words “SIGILLUM ACADEMIAE HARVARDIANAE IN NOV ANG”]

[end of document]

Because of the relatively late date of Harvard’s commencement, Dykes was the third Black woman to formally receive the Ph.D. degree that year. Alvin Goulbourne, photographer. “Eva B. Dykes’ Radcliffe College doctoral degree.” Eva B. Dykes Collection/Courtesy of Oakwood University Archives

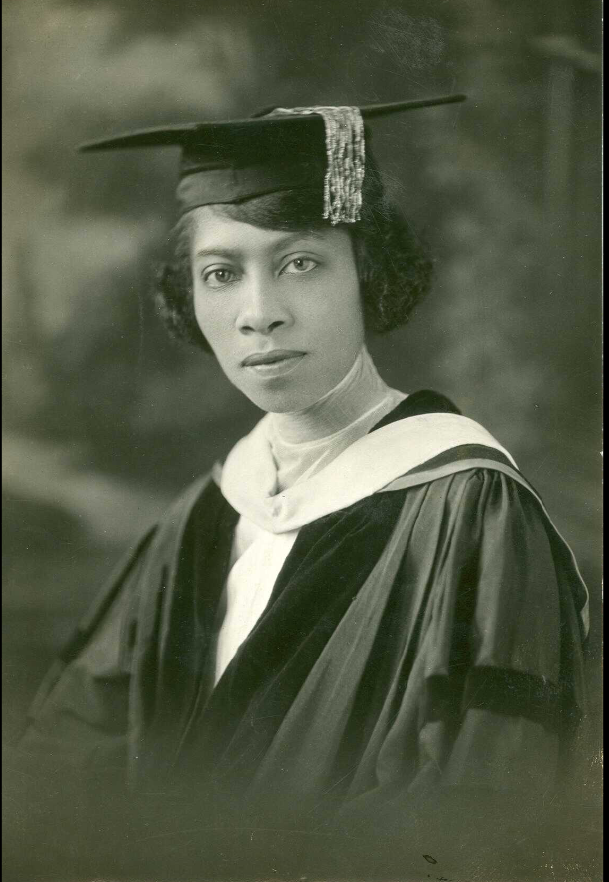

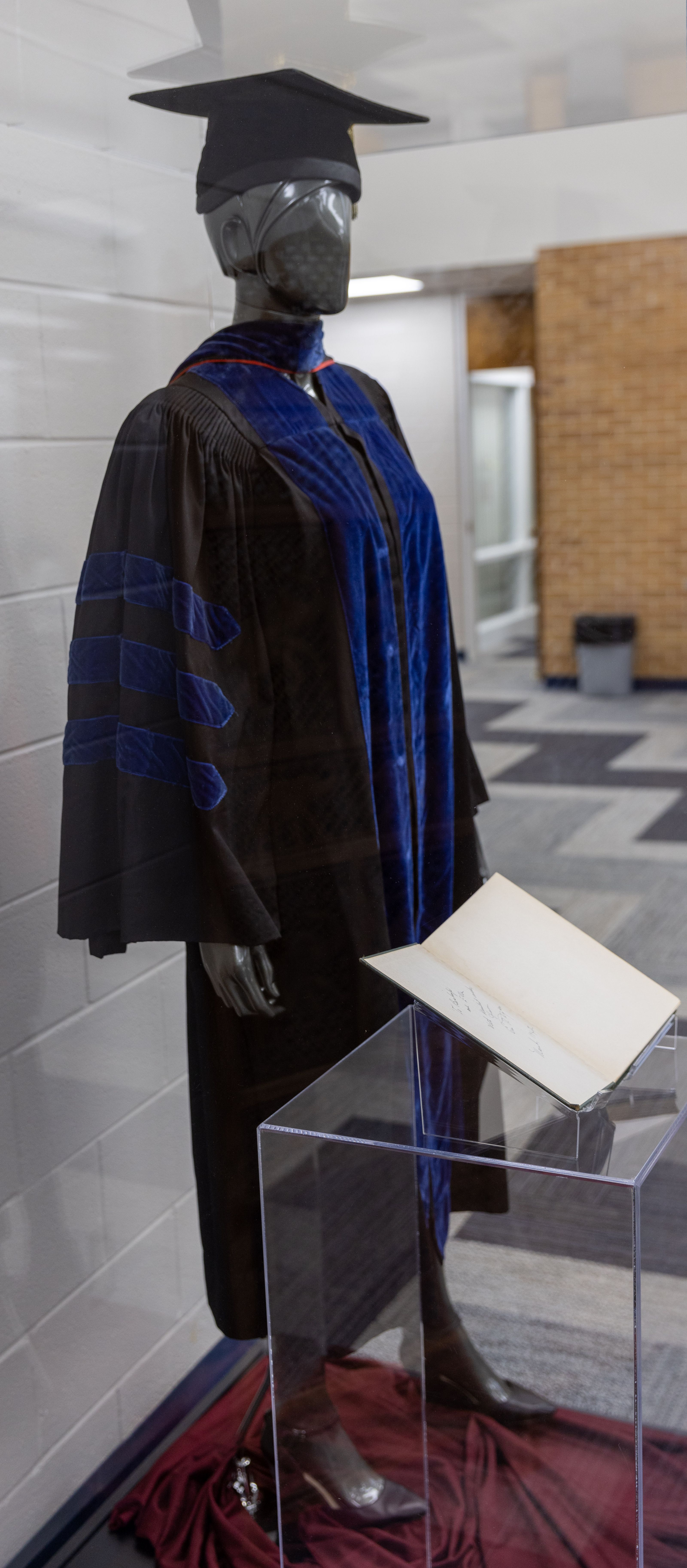

When asked to discuss her extraordinary achievement later in life, Dykes refused to call herself the first. Instead, she celebrated the fact that she was one of the first three Black women to earn the Ph.D. in 1921. Alvin Goulbourne, photographer. “Eva B. Dykes’ regalia.” Eva B. Dykes Collection/Courtesy of Oakwood University Archives

A Commitment to Service through Education and Music

After leaving Radcliffe, Dykes devoted her decades-long career to teaching, first returning home to Washington, DC, and accepting posts at the segregated Dunbar High School and later at her alma mater Howard University. She taught English at Howard from 1929 to 1944, where she was voted the best all-round teacher by the College of Liberal Arts faculty.

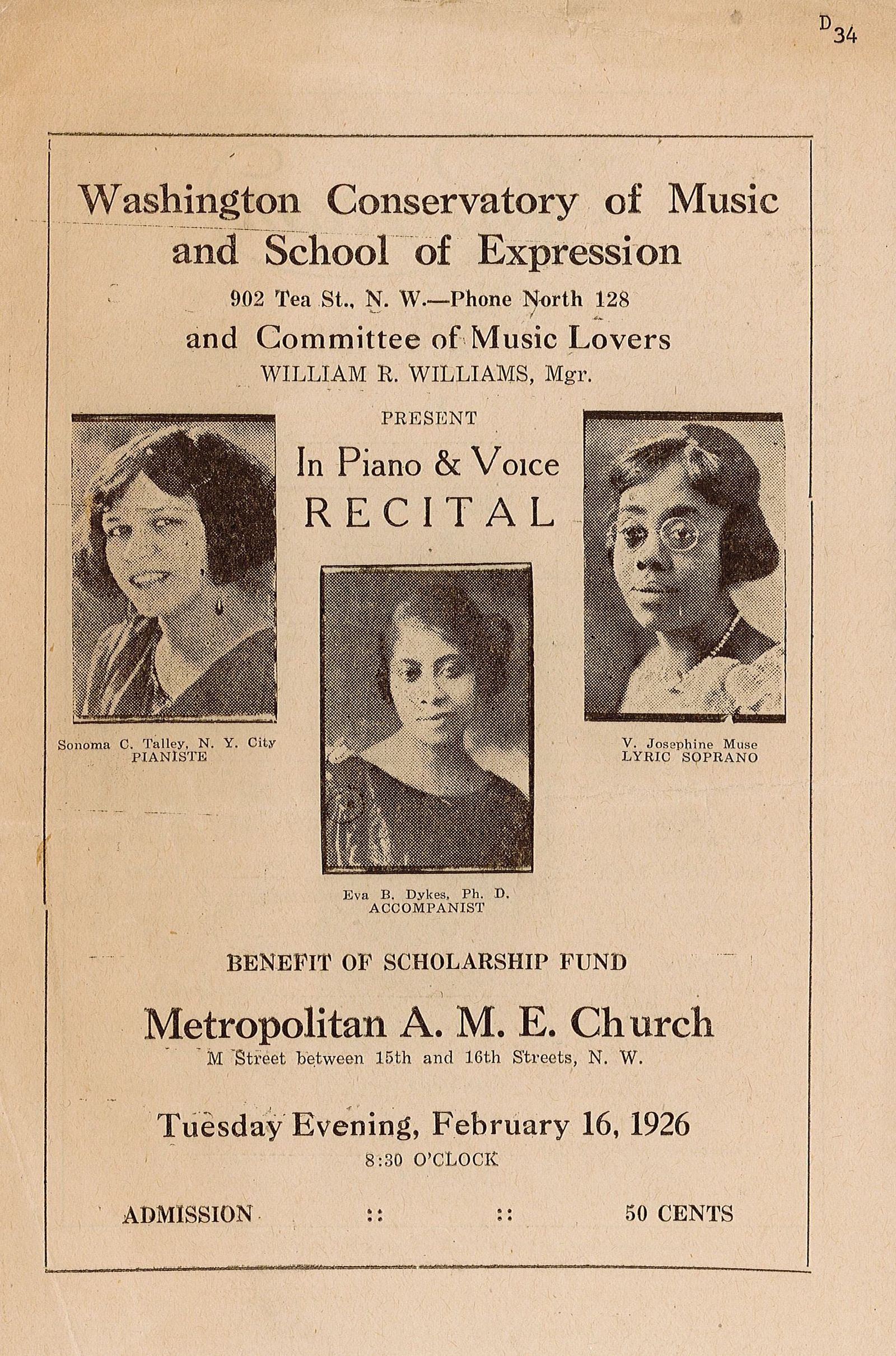

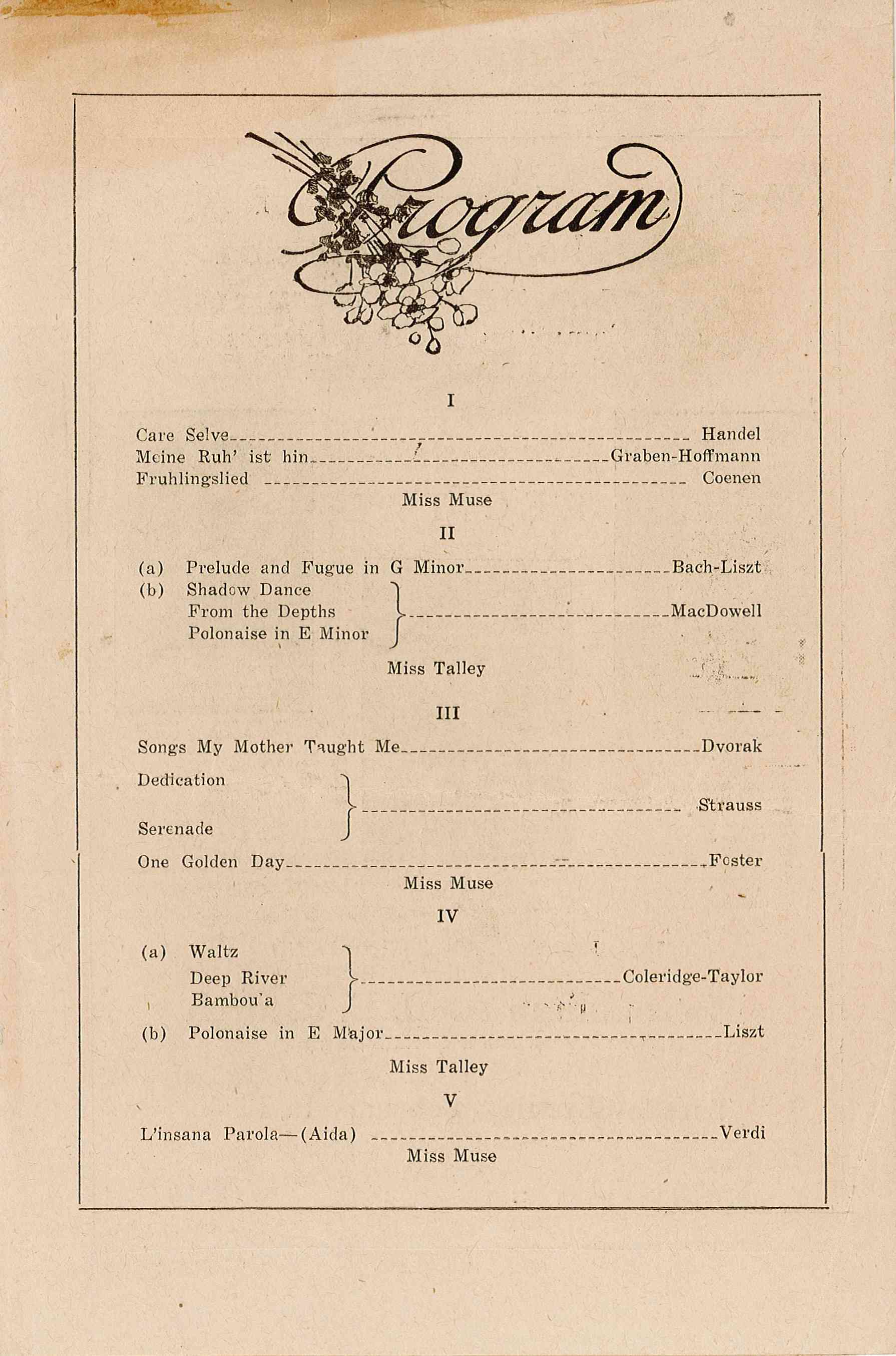

Music also played a large role in her life. An accomplished musician, she had been an organist at local churches as early as age 7, even though her feet barely reached the pedals. She was also a composer, and in 1926, Opportunity: Journal of Negro Life — a leading publication of the Harlem Renaissance — honored two of her compositions: “Lady O’ Mine” and “To the Black Beloved.” Throughout her adult life Dykes was a celebrated accompanist, and often contributed her musical talents to local philanthropic and educational causes.

Open and scroll to read the poster transcript

[all text centered on the page and surrounded by a single line border]

Washington Conservatory of Music

and School of Expression

902 Tea St., N.W. — Phone North 128

and Committee of Music Lovers

WILLIAM R. WILLIAMS, Mgr.

PRESENT

In Piano & Voice

R E C I T A L

[left: black and white bust portrait photograph of a light-skinned woman with dark hair in a loose bob]

Sonoma C. Talley, N. Y. City

PIANISTE

[center: black and white bust portrait photograph of a dark-skinned woman with dark hair pulled back and up in a formal style]

Eva B. Dykes, Ph. D.

ACCOMPANIST

[center: black and white bust portrait photograph of a dark-skinned woman with dark hair pulled back from her face]

V. Josephine Muse

LYRIC SOPRANO

BENEFIT OF SCHOLARSHIP FUND

Metropolitan A. M. E. Church

M Street between 15and 16 Streets, N. W.

Tuesday Evening, February 16, 1926

8:30 O’CLOCK

ADMISSION :: :: 50 CENTS

[end of page]

[click here for the next page of the musical program transcript]

Music played a large role in Dykes’ life. An accomplished organist, she was a celebrated accompanist and often contributed her talents to public concerts and fundraisers for philanthropic causes. Washington Conservatory of Music and School of Expression and Committee of Music Lovers. “In Piano & Voice RECITAL.” February 16, 1926. Eva B. Dykes Collection/Courtesy of Oakwood University Archives

Open and scroll to read the program transcript

[all text surrounded by a single line border]

[large cursive script font with flowers drawn interwoven with the word] Program

I

Care Selve _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ Handel

Mein Ruh’ ist him _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _Graben-Hoffman

Fruhlingslied _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _Coenen

Miss Muse

II

( a ) Prelude and Fugue in G Minor _ _ _ _ _ Bach-Liszt

( b ) Shadow Dance

From the Depths }_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ Dvorak

Polonaise in E Minor

Miss Talley

III

Songs My Mother Taught Me_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ Dvorak

Dedication

Serenade }_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ Strauss

One Golden Day_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ Foster

Miss Muse

IV

( a ) Waltz

Deep River }_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _Coleridge-Taylor

Bambou’a

( b ) Polonaise in E Major _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ Liszt

Miss Talley

V

L’insana Parola — (Aida) _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _Verdi

Miss Muse

[end of page; end of program]

Washington Conservatory of Music and School of Expression and Committee of Music Lovers. “In Piano & Voice RECITAL.” February 16, 1926. Eva B. Dykes Collection/Courtesy of Oakwood University Archives

Lifting Up Black History and Black Voices

Dykes was a scholar of English and Black literature. Her early scholarship focused on how celebrated figures in 18th- and 19th-century English literature thought about race and slavery. In her work, she sought to expose racial prejudice as an impediment to the nation moving spiritually, morally, and economically forward.

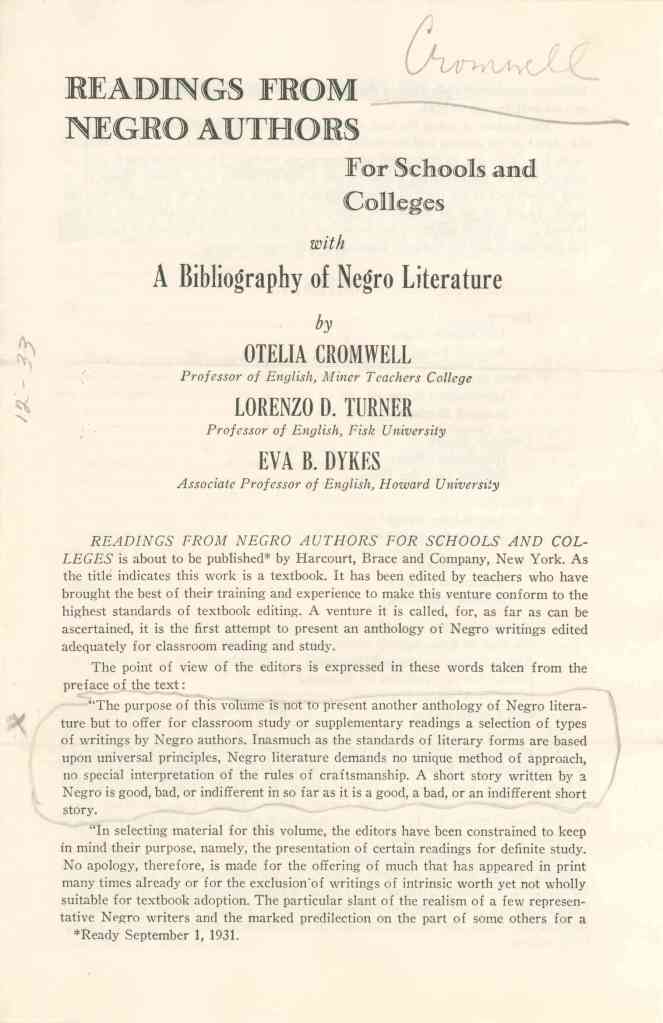

Dykes was also committed to elevating the prose, poetry, and song of Black creators, which she hoped would inspire young Black people. In 1931, she co-edited a survey of early Black literature with Otelia Cromwell and Lorenzo Dow Turner, a textbook designed to bring writing by Black authors into American classrooms.

Open and scroll to read the page transcript

[handwritten and underlined in pencil at top right] Cromwell

READINGS FROM NEGRO AUTHORS For Schools and Colleges with

A Bibliography of Negro Literature

by

OTELIA CROMWELL

Professor of English, Miner Teachers College

LORENZO D. TURNER

Professor of English, Fisk University

EVA B. DYKES

Associate Professor of English, Howard University

READINGS FROM NEGRO AUTHORS FOR SCHOOLS AND COLLEGES is about to be published* by Harcourt, Brace and Company, New York. As the title indicates this work is a textbook. It has been edited by teachers who have brought the best of their training and experience to make this venture conform to the highest standards of textbook editing. A venture it is called, for, as far as can be ascertained, it is the first attempt to present an anthology of Negro writings edited adequately for classroom reading and study.

The point of view of the editors is expressed in these words taken from the preface of the text:

[the following paragraph is circled in pencil with an X marked next to it in pencil in the left margin]

“The purpose of this volume is not to present another anthology of Negro literature but to offer for classroom study or supplementary readings a selection of types of writings by Negro authors. Inasmuch as the standards of literary forms are based upon university principles, Negro literature demands no unique method of approach, no special interpretation of the rules of craftsmanship. A short story written by a Negro is good, bad, or indifferent in so far as it is a good, a bad, or an indifferent short story.

[end of penciled circle]

“In selecting material for this volume, the editors have been constrained to keep in mind their purpose, namely, the presentation of certain readings for definite study. No apology, therefore, is made for the offering of much that has appeared in print many times already or for the exclusion of writings of intrinsic worth yet not wholly suitable for textbook adoption. The particular slant of the realism of a few representative Negro writers and the marked predilection on the part of some others for a […]

* Ready September 1, 1931.

[end of document]

Her 1942 book “The Negro in English Romantic Thought” demonstrated opposition to slavery among well-known authors of the 18th and 19th century — opposition that had previously been overlooked — and throughout her career she published articles in the Negro History Bulletin and The Journal of Negro History exploring similar topics. In a book review published in The Journal of Negro History in 1944, she argued that the examination of the lives and work of Black authors and artists powerfully illustrated

the variety of ways in which that cancer of American life, race prejudice, is eating the spiritual bowels of American morale and undermining the progress of the United States as a nation, — prejudice in labor, in education, in journalism, in the artistic world, in the courts of justice, in the church and in society in general.

Dykes reflected on her decision to study and teach literature in a 1968 interview with The Huntsville [Alabama] Times:

When looked at quickly, literature doesn’t seem to stand up as a very practical subject. Certainly, one doesn’t construct a building with a degree in English, but literature helps a people’s spirit and helps preserve the language. It can be very practical, too — I know it can change a reader’s attitude and possibly even alter his behavior.

Oakwood University

Spurred on by her faith, in 1944, Dykes joined the faculty of the Seventh-day Adventist-affiliated historically Black Oakwood College (now Oakwood University) in Huntsville, Alabama, where she taught until her retirement in 1968, and again from 1970 to 1975.

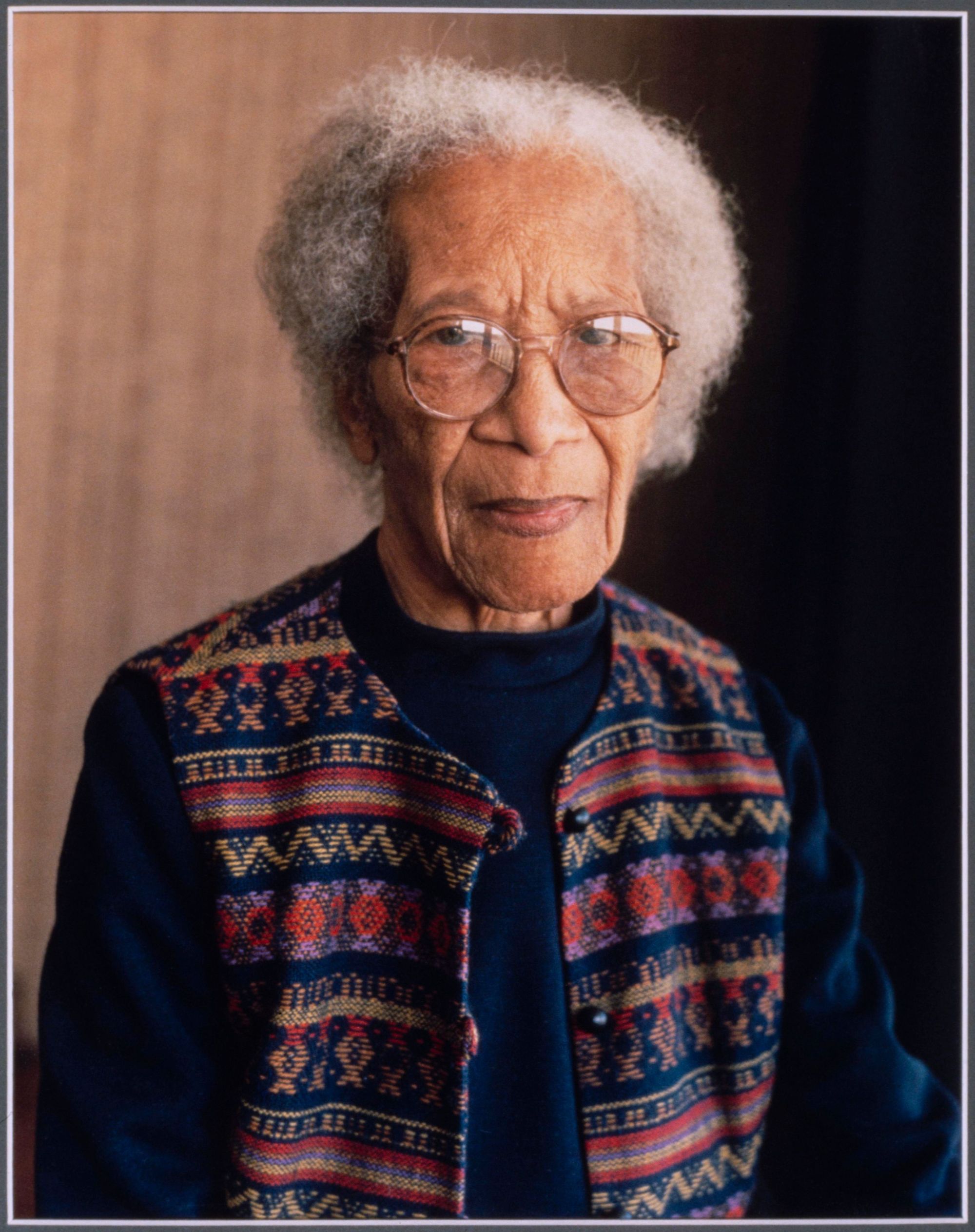

Dykes was the institution’s first faculty member to hold a Ph.D. She served as chair of the English Department and the Division of Humanities and a played pivotal role in helping Oakwood secure accreditation in 1958. She also used her musical talents in support of the school and its students, founding the world-renowned choir the Aeolians of Oakwood University. Today the group is recognized as “an authoritative exponent of Negro spirituals and Work songs which express the yearnings of their forefathers to be free.”

In 1973, Oakwood renamed its library for Dykes in tribute to her service to the institution and countless other contributions to the lives of Black students, staff, and scholars. She died in 1986 and is buried in Huntsville, near the Oakwood campus.

Selected Sources

Bacher, Marina. 2018. “Pioneer African American Educators in Washington, DC : Anna J. Cooper, Mary Church Terrell, and Eva B. Dykes”. Zürich: Lit Verlag.

Dykes, Eva B.. Review: Rising Above Color by Philip Henry Lotz. The Journal of Negro History 29, no. 2 (1944): 222–24.

“DYKES, Eva.” Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University. Washington, DC.

Eva Dykes (1893–1986), Huntsville, Alabama. Interviewed by: Merze Tate, November 30 and December 1, 1977. Interviews of the Black Women Oral History Project, 1976–1981, OH-31: T-32. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute.

“Eva Beatrice Dykes.” The Report of the Presidential Committee on Harvard & the Legacy of Slavery. Harvard Radcliffe Institute. Accessed July 20, 2023.

Williams, Dewitt S. She Fulfilled the Impossible Dream: The Story of Eva B. Dykes. Xulon Press, 2016.

More profiles

Alberta Virginia Scott

Alberta Virginia Scott created a quietly powerful legacy as the first Black woman to graduate from Radcliffe College.

Frances O. Grant

Frances O. Grant, the first Black woman elected to the Iota Chapter of Phi Beta Kappa, graduated from Radcliffe College in 1917. She went on to an extraordinary career as an educator, primarily at the…

Marita Bonner

Marita Bonner Occomy, an award-winning author and song writer who published under her maiden name Marita Bonner, graduated from Radcliffe College in 1922.