Frances O. Grant

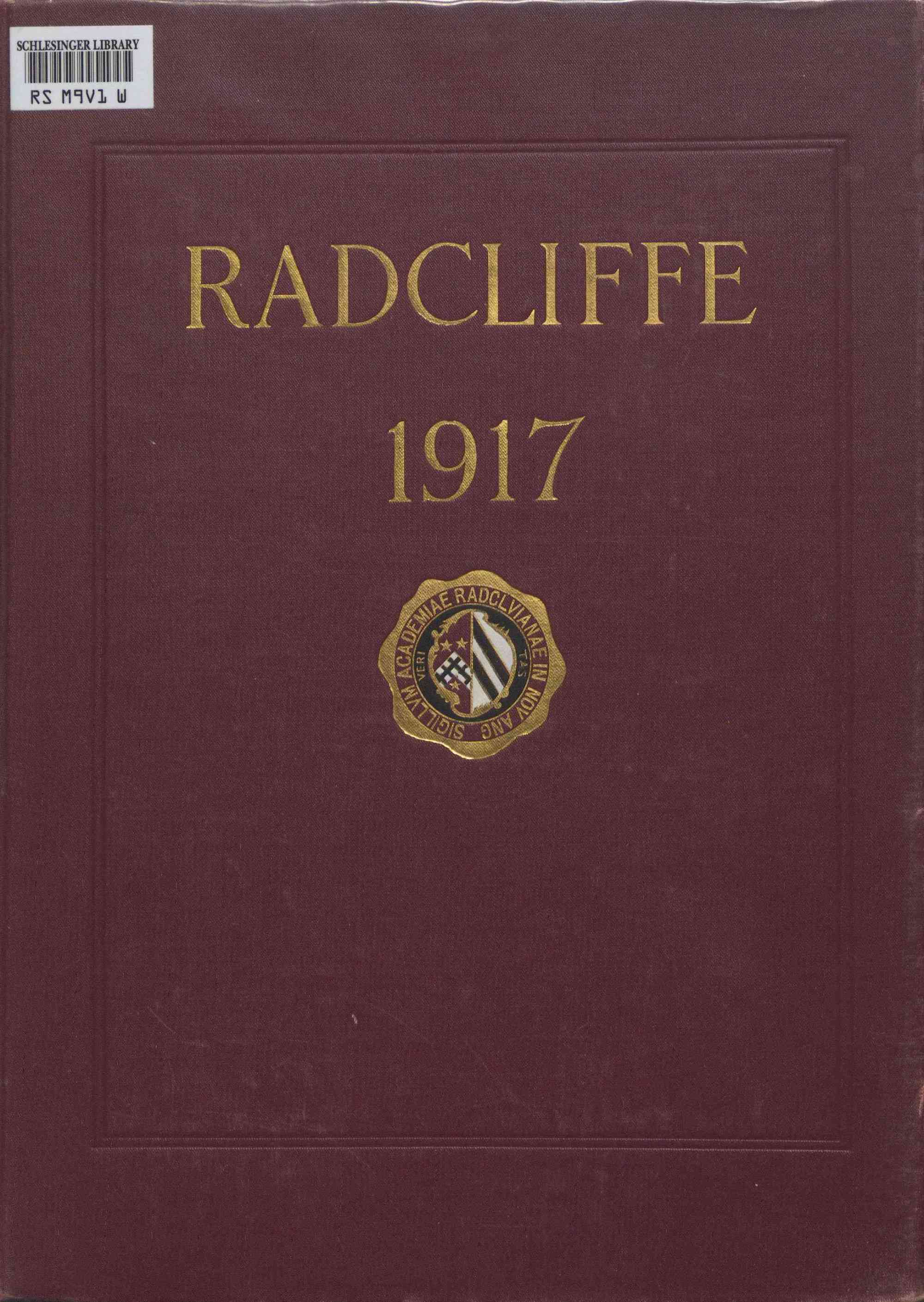

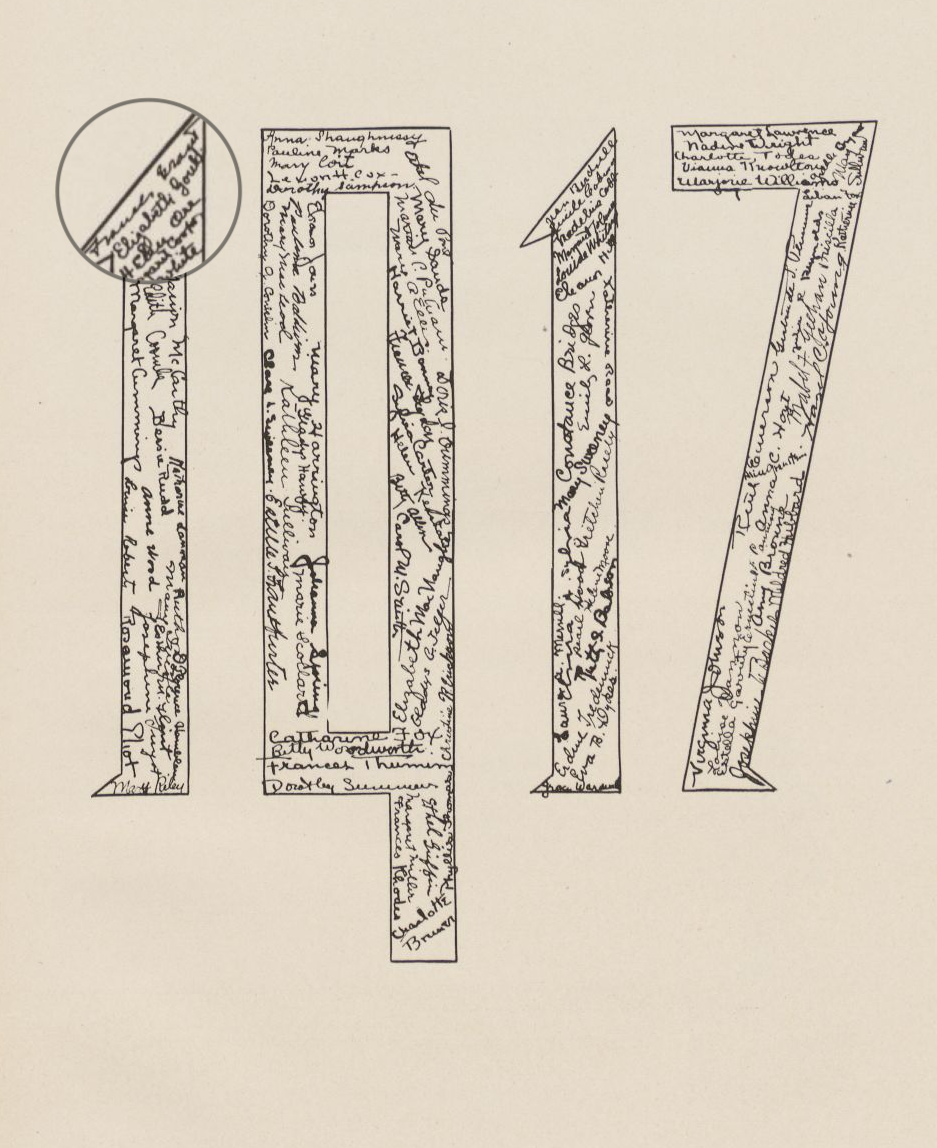

Class of 1917

Frances O. Grant

Frances O. Grant, the first Black woman elected to the Iota Chapter of Phi Beta Kappa, graduated from Radcliffe College in 1917. She went on to an extraordinary career as an educator, primarily at the Bordentown Manual Training and Industrial School in New Jersey.

School: Radcliffe College

Degree: A.B.

Area of Impact: Education

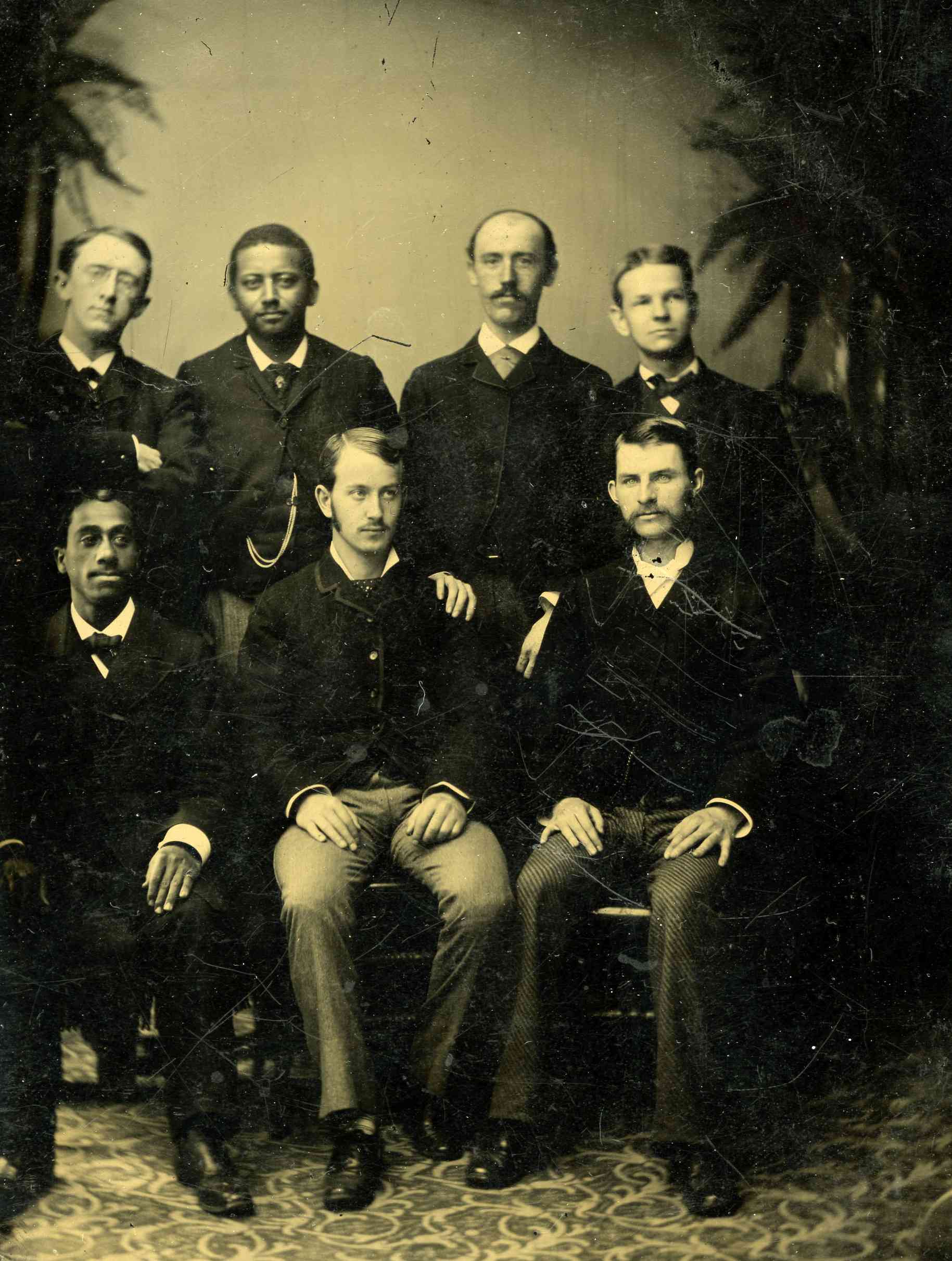

Harvard and Radcliffe Legacies

Frances Olivia Grant was born in Boston on June 30, 1895, the eldest daughter of Fannie Bailey and George Franklin Grant. Her father was a Harvard-educated dentist and an inventor who held patents for both an artificial palate used to treat patients with a cleft palate and the first golf tee. Dr. Grant (D.M.D. 1870) was the second Black person to graduate from Harvard Dental School (now Harvard School of Dental Medicine), and therefore only the second Black person to graduate from any dental school in the United States. He was hired by the school’s Department of Mechanical Dentistry as an assistant in 1871, and went on to serve as an instructor from 1883 to 1903 — the first Black faculty member in Harvard history. He served as the president of the Harvard Dental Alumni Association in 1882 and as president of the Harvard Odontological Society in 1883.

Grant’s father was not her only tie to the University. Her cousin Gertrude Baker (A.B. 1900) was the second Black woman to graduate from Radcliffe College.

The Grant family’s history exemplifies the spirit of Black resilience. Grant’s paternal grandfather, Tudor E. Grant, escaped from bondage and became a fervent abolitionist who helped enslaved people gain their freedom via the Underground Railroad. In an interview for the Schlesinger Library Black Women Oral History Project, Grant, whose maternal grandmother was enslaved by a family in Fairfax County, Virginia, recalled how her father shared memories of his family helping enslaved people cross the border into Canada at Oswego, New York.

Thanks to her father’s successful dental practice and academic career, Grant told the Oral History Project interviewer, she led a charmed life in her early childhood on Charles Street in Boston’s Beacon Hill neighborhood. “His appointment book read like the social register,” she recalled. The family owned summer houses, first in Massachusetts and then New Hampshire. When asked whether she felt “different” from her presumably white neighbors, her answer was, “No, never.” She was raised to have complete confidence in herself, which she attributed to the sense of security her parents instilled in her. And, as an adult, “I never went in anywhere, feeling that I … was not going to be served … that I was not going to get whatever was there” (ellipses in original).

Grant thrived academically at the highly competitive Girls’ Latin School, the first public college preparatory school for girls in the United States, where her teachers’ dedication to and passion for their work influenced her decision to become an educator.

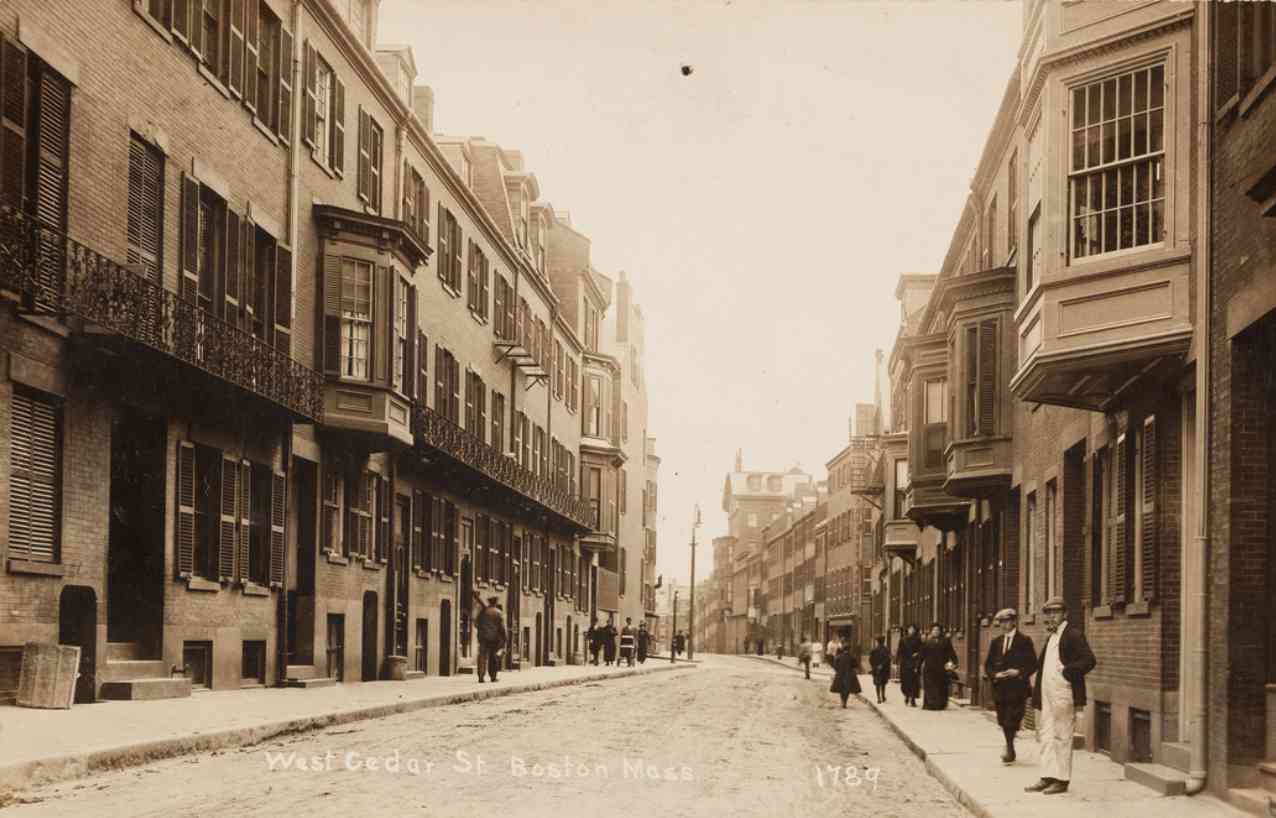

Until Dr. George F. Grant’s death in 1910, the family lived at 108 Charles St. in Boston’s Beacon Hill neighborhood — one block from the site of this 1905 photo. “Postcard, West Cedar Street, Boston, Mass..”/Historic New England (Public Domain)

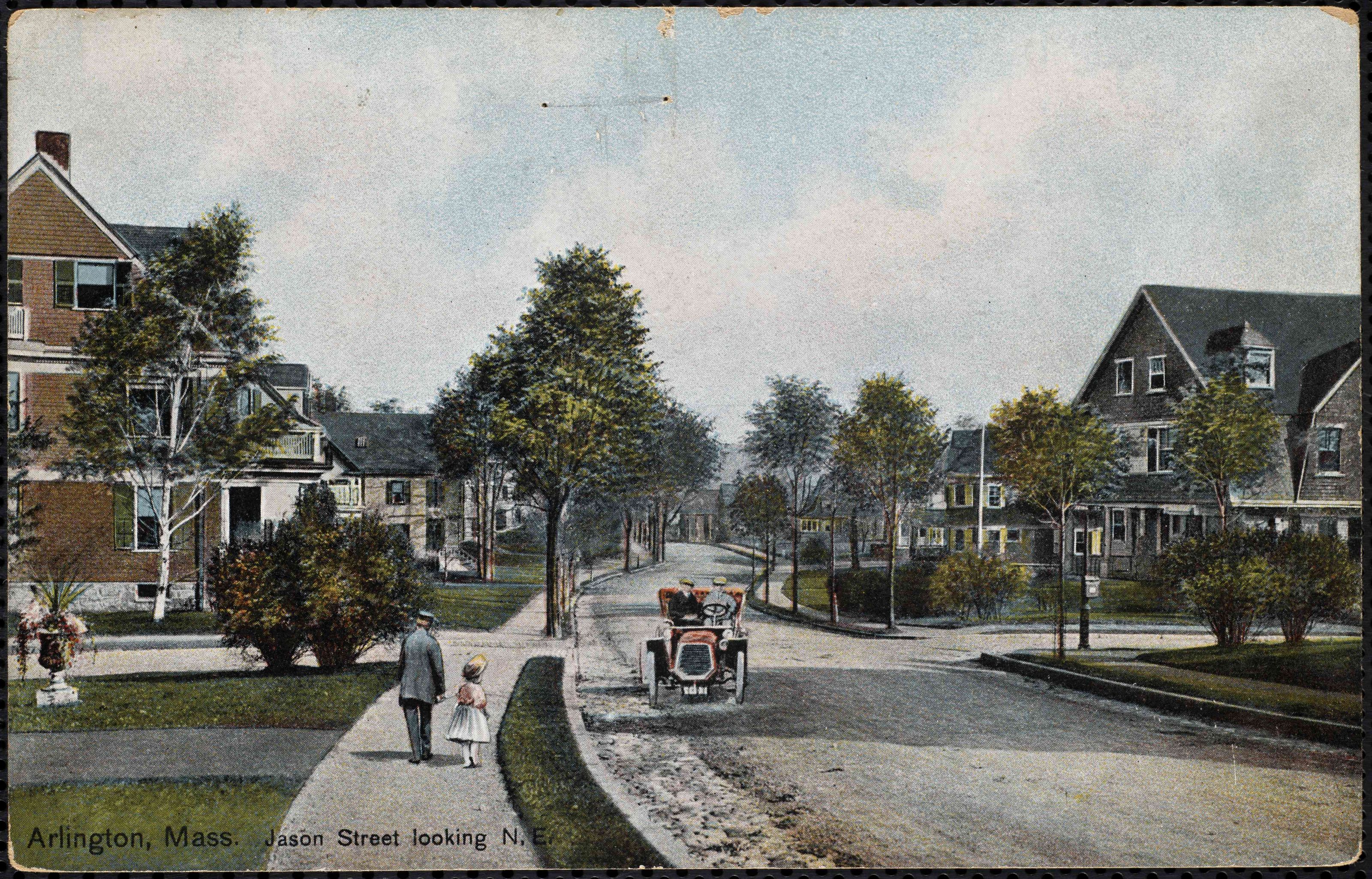

The Grant family had a summer home in Arlington, Massachusetts, prior to Dr. George F. Grant’s death in 1910. “Arlington, Mass. Jason Street looking n.e..” Postcard. ca. 1907–1981. Robbins Library Local History Room Postcard Collection/Digital Commonwealth (CCBY-NC-ND)

The death of her father in 1910 was an eye-opening experience for Grant in more ways than one. The family had to leave their Charles Street home, and her mother returned to work at the Riverside Press in Cambridge. Finding housing elsewhere proved challenging because of racial discrimination. Grant’s fair-skinned mother eventually found an apartment near the Latin School, but after she turned up with her darker-skinned daughters, the landlord sold the building to break the lease.

The apartment incident was, she recalled in her Oral History Project interview, “my first real poignant introduction to prejudice.”

My father’s death produced not only complete chaos as far as our lives were concerned, but brought to me the first realization that being a Negro made a difference in what I could have and what I could get.

Despite her family’s reduced circumstances, Grant thrived academically. Upon her graduation from the Girls’ Latin School in 1913, she was named valedictorian and also received the school’s highest honor, the Griswold Scholarship of $25 — a significant sum, given that Radcliffe’s annual tuition was then just $150. She also earned scholarships that funded most of her education for the next four years.

Because of the college’s racist housing rules, Grant lived a half-mile from campus in a Cambridge apartment with her mother and sister.

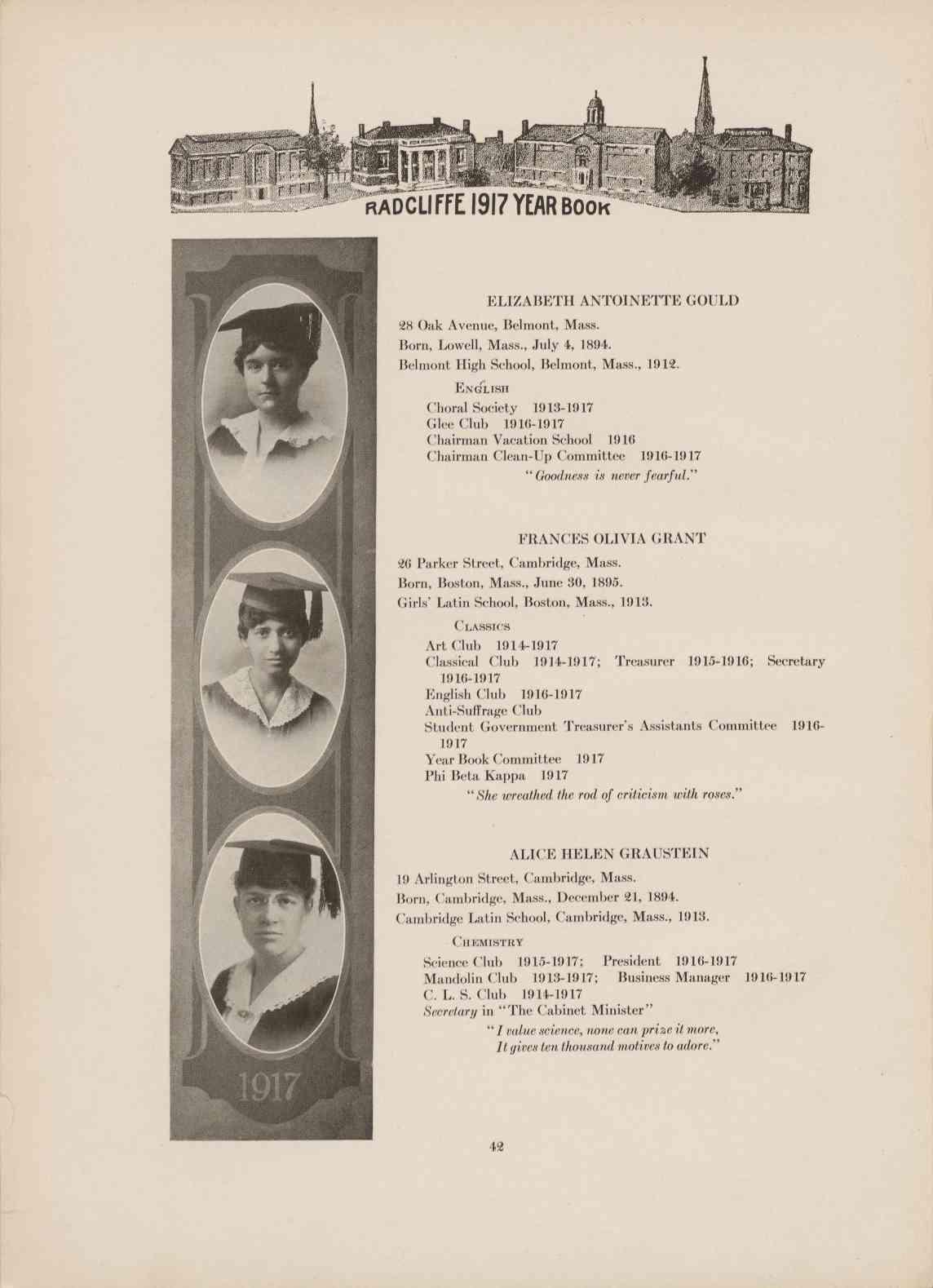

Grant was involved in several student clubs, including the Classical Club, for which she served as treasurer and then secretary; the English Club; the Art Club; the theatrical club, the Idler; the Music Committee; the Radcliffe Guild; the Student Government Treasurer’s Assistants Committee; and the Yearbook Committee. Perhaps surprisingly, she was also a member of the Anti-Suffrage Club.

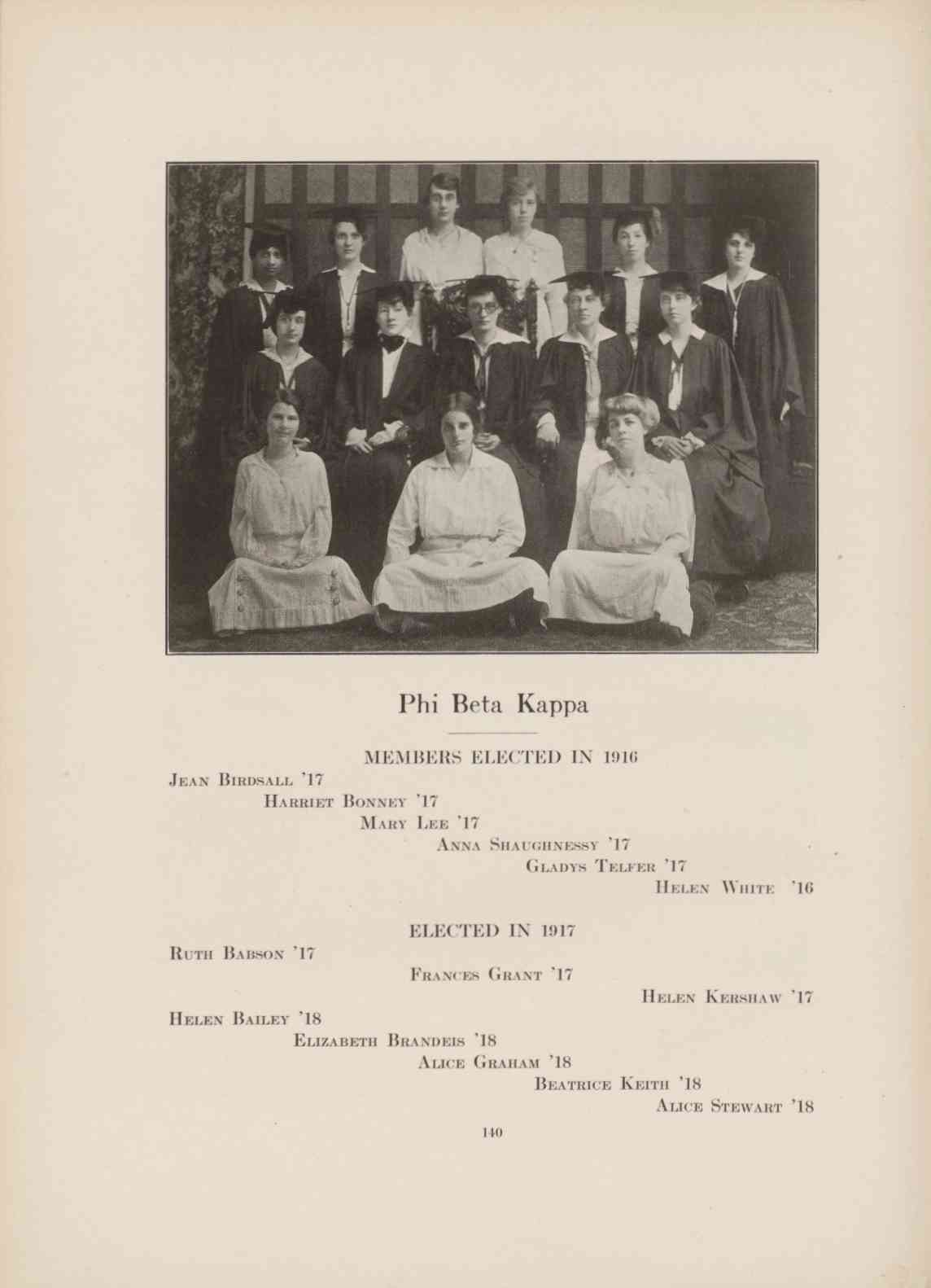

She was equally active and successful in the classroom. When Grant first arrived at Radcliffe, she was delighted to find her friend and former Latin School classmate, Natalie Walker — who was white — had been assigned as her senior advisor. When Radcliffe’s Iota Chapter of Phi Beta Kappa was established in 1914 and Walker became a member, Grant recalled in her Oral History Project interview, she set her sights on being elected as well: “I always felt that if I could […] I’d be very much delighted. Fortunately, I was able to do that.” In 1916, she became the first Black person elected to the Iota Chapter and the second Black woman in the nation to hold the key.

Grant’s social life flourished at Radcliffe. She had a “very cosmopolitan” group of young women of all ethnic and social classes. She visited some of her friends’ homes, but mixed-race social events with men and women “were practically out of the question.” Like W.E.B. Du Bois (A.B. 1890, A.M. 1891, Ph.D. 1895) before her, Grant also happily spent time with other Black students at Boston-area colleges who attended parties, football games, and other activities together.

Grant graduated magna cum laude in 1917, with an A.B. in classics, marking “the close of four delightful years at Radcliffe.” She later earned a master’s degree in education from New York University.

An Extraordinary Educator

Grant went on to have a long and influential teaching career. There were not many teaching opportunities for Blacks in Boston, but with the help of fellow Radcliffe alumna Eva Hall (A.B. 1903) she secured a position teaching English, history, and Latin at the New Jersey Manual Training and Industrial School for Colored Youth, located in Bordentown, New Jersey — often referred to simply as the Bordentown School.

There, she told the Black Women’s Oral History Project, “I found myself for the first time in life in a completely segregated outfit.”

When she arrived, the school ran from sixth to 10th grade and its curriculum focused primarily on vocational skills. Grant — an active member in the National Organization of Teachers of Colored Children and the National Association of College Women, which advocated for quality education for Black students — joined forces with the principal, Harvard graduate W. R. Valentine (A.B. 1904), to transform the school into a model, state-certified ninth through 12th grade high school from which students graduated with a traditional diploma as well as a vocational skill.

Through the Organization of Teachers of Colored Children, Frances Grant helped to create professional development opportunities for teachers in southern New Jersey. “18th Annual Meeting, Organization of Teachers of Colored Children, 14 May 1932.” Manual Training and Industrial School for Colored Youth at Bordentown, New Jersey. Photographs, ca. 1930s–1950s/Courtesy of the New Jersey State Archives; Department of State

Open and scroll to read the article transcript

Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority’s Campaign for Vocational Guidance

[horizontal dividing line]

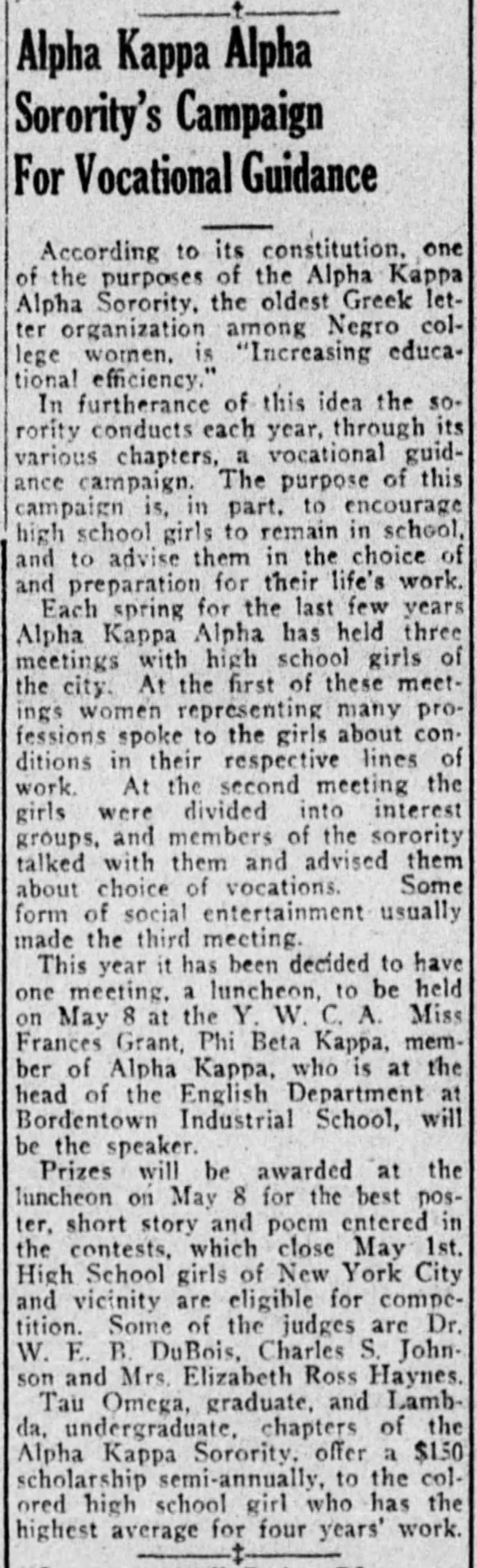

According to its constitution, one of the purposes of the Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, the oldest Greek letter organization among Negro college women, is “Increasing educational efficiency.”

In furtherance of this idea the sorority conducts each year, through its various chapters, a vocational guidance campaign. The purpose of this campaign is, in part, to encourage high school girls to remain in school, and to advise them in the choice of and preparation for their life’s work.

Each spring for the last few years Alpha Kappa Alpha has held three meetings with high school girls of the city. At the first of these meetings women representing many professions spoke to the girls about conditions in their respective lines of work. At the second meeting the girls were divided into interest groups, and members of the sorority talked with them and advised them about choice of vocations. Some form of social entertainment usually made the third meeting.

This year it had been decided to have one meeting, a luncheon, to be held on May 8 at the Y. W. C. A. Miss Frances Grant, Phi Beta Kappa, member of Alpha Kappa, who is at the head of the English Department at Bordentown Industrial School, will be the speaker.

Prizes will be awarded at the luncheon on May 8 for the best poster, short story and poem entered in the contests, which close May 1st. High School girls of New York City and vicinity are eligible for competition. Some of the judges are Dr. W. E. B. DuBois, Charles S. Johnson and Mrs. Elizabeth Ross Haynes.

Tau Omega, graduate, and Lambda, undergraduate, chapters of the Alpha Kappa Sorority, offer a $150 scholarship semi-annually, to the colored high school girl who has the highest average for four years’ work.

[horizontal line border]

[end of article]

Frances Grant’s efforts to improve educational opportunities for Black people included dedicated efforts to encourage young Black women to complete high school. In 1926, she was the featured speaker at a meeting of the Alpha Kappa Alpha sorority, where she spoke to students about her career as an educator. “Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority’s Campaign for Vocational Guidance.” The New York Age. May 1, 1926/Public Domain

Speaking in her Oral History Project interview about this increased emphasis on academic learning, Grant said,

I didn’t feel that because I was in a wholly Negro setup, that there should be a set of Negro standards. I felt that there should be standards, and that the students, if they were to go out in the world which was not wholly Negro, must be taught to meet the standards of that world.

As part of these reforms she introduced a course on “Negro history,” using Harvard graduate Carter G. Woodson’s (Ph.D. 1912) The Negro in Our History (1922) as a textbook.

Open and scroll to read the article transcript

Big Field Day Program At Bordentown Institute

[horizontal dividing line]

Bordentown, N. J. — An elaborate field day program will be presented at Bordentown Manuel Training School on Decoration Day, Monday, May 3. An exhibition of the physical training department by boys and girls will take place in the morning, Miss Vivienne Hollis ,director of girls physical training, Walter M. Pettey, in charge of the boys.

In the afternoon field events and a baseball game between the school team and the Atlas A. A. of Long Branch, N. J., in the evening an operetta, “The Drum Major,” under the direction of Fred J. Work, teacher of vocal music, and Miss Frances Grant. The Glee Club will be in evidence.

[end of article]

Grant believed that if her students “were to go out in the world which was not wholly Negro, [they] must be taught to meet the standards of that world.” She enhanced Bordentown’s curriculum, and founded a student newspaper and a drama club that showcased the students’ talents through events such as this 1926 public Field Day exhibition. “Big Field Day Program at Bordentown Institute.” The New York Age. May 29, 1926/Public Domain

Open and scroll to read the article transcript

Moorestown Wins Choir Contest at Bordentown

[horizontal dividing line]

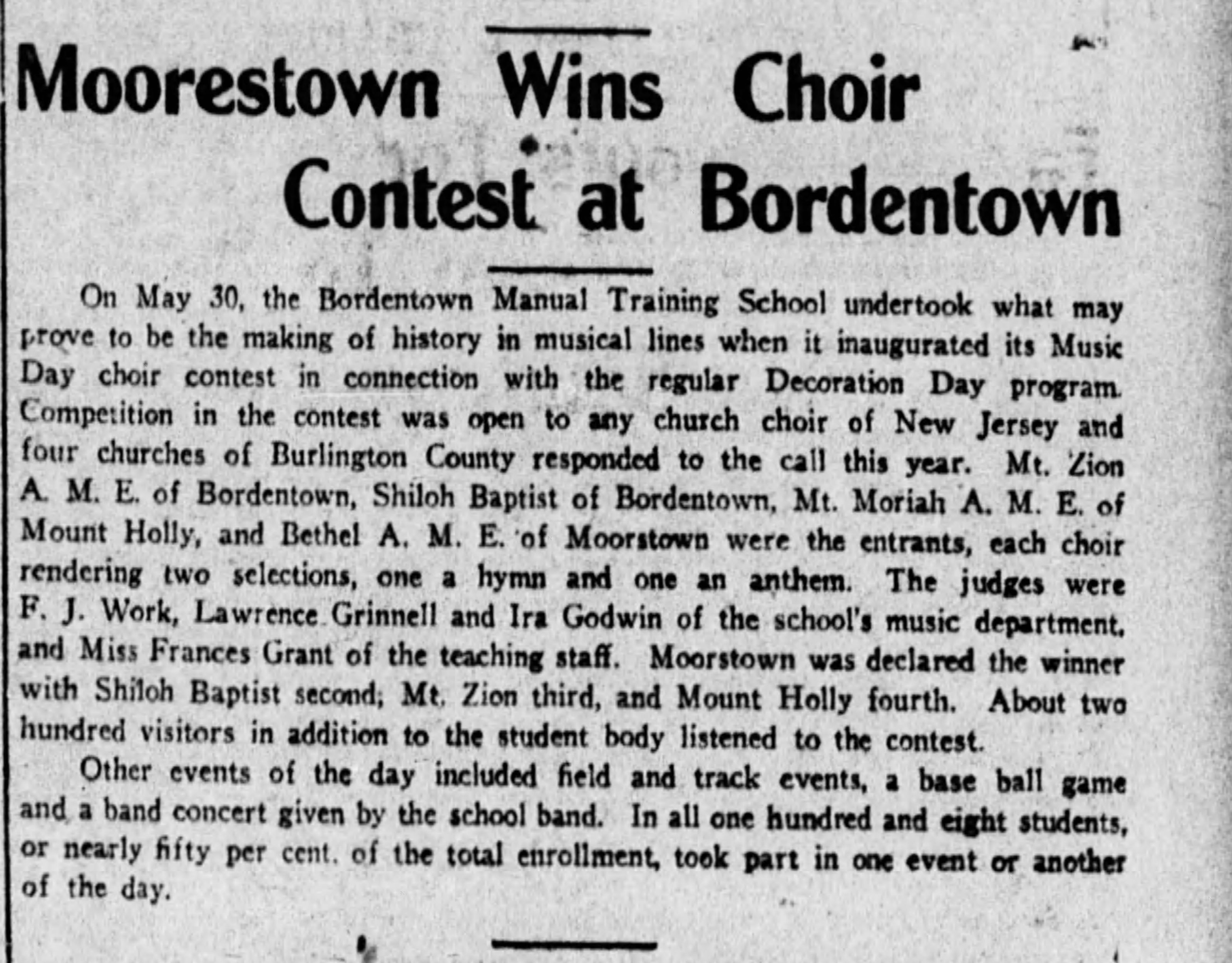

On May 30, the Bordentown Manual Training School undertook what may prove to be the making of history in musical lines when it inaugurated its Music Day choir contest in connection with the regular Decoration Day program. Competition in the contest was open to any church choir of New Jersey and four churches of Burlington County responded to the call this year. Mt. Zion A. M. E. of Bordentown, Shiloh Baptist of Bordentown, Mt. Moriah A. M. E. of Mount Holly, and Bethel A. M. E. of Moorstown were the entrants, each choir were the entrants, each choir rendering two selections, one a hymn and one an anthem. The judges were F. J. Work, Lawrence Grinnell and Ira Godwin of the school’s music department, and Miss Frances Grant of the teaching staff. Moorstown was declared the winner with Shiloh Baptist second, Mt. Zion third, and Mount Holly fourth. About two hundred visitors in addition to the student body listened to the contest.

Other events of the day included field and track events, a base ball game and a band concert given by the school band. In all one hundred and eight students, or nearly fifty per cent. of the total enrollment, took part in one event or another of the day.

[horizontal dividing line]

[end of article]

Grant’s support for the arts extended beyond the drama club. In 1924, she served as one of the judges at the Bordentown School’s inaugural choir contest. “Moorestown Wins Choir Contest at Bordentown.” The New York Age. June 7, 1924/Public Domain

“The Tuskegee of the North”

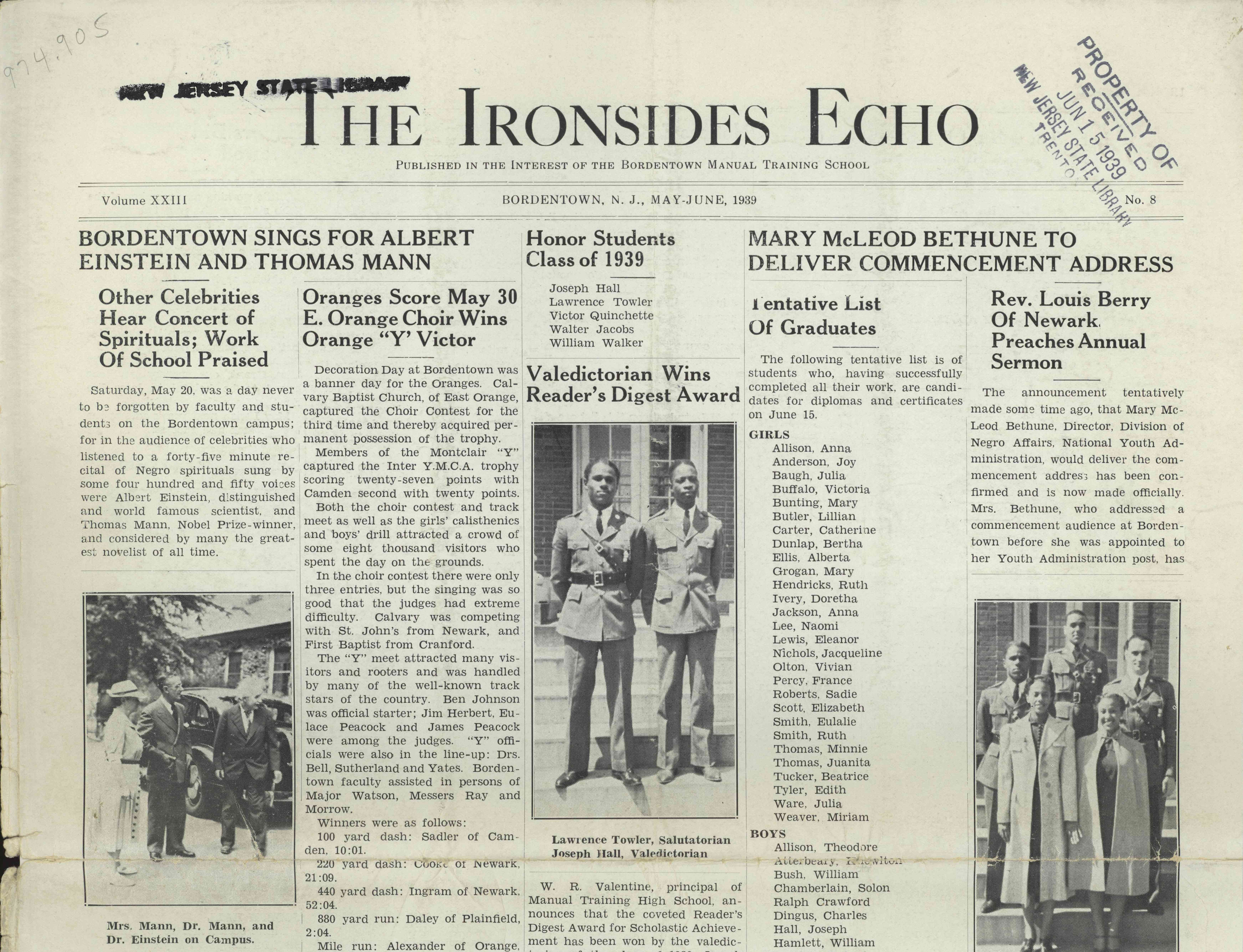

In addition to enhancing the curriculum, Grant founded a drama club and a school newspaper, The Ironsides Echo. She was confident that the paper was worthy of comparison with other school newspapers on a national level, and under her leadership it won multiple prizes from organizations including the National Scholastic Association. In keeping with her insistence on preparing her students for the world beyond their segregated school, the paper became an important form of outreach and connection. Grant recalled in her oral history interview:

The Ironsides Echo, in addition to entering these competitions, set up a large exchange; white and Negro schools exchanged with us. When [World War II] broke out, we sent The Ironsides Echo, over a hundred, to everybody all over the world. And interesting enough, when some of the soldiers came on back […] they would come by the school and leave us five or ten dollars to pay for the postage, and tell about getting The Ironsides Echo, when they were in foxholes in New Guinea and having a little sense of belonging, and having the feeling that somebody cared and was interested.

Grant also invited prominent Black figures such as the great educator and philanthropist Mary McLeod Bethune; civil rights activist and scholar W.E.B. Du Bois; lawyer, poet, former executive secretary of the NAACP, and leader of the Harlem Renaissance James Weldon Johnson; and actor and activist Paul Robeson to speak to students, part of her effort to instill in them an awareness of Black achievement. Albert Einstein and Eleanor Roosevelt were also guests. Thousands of Black people from along the east coast attended these events at Bordentown, which ultimately became known as “the Tuskegee of the North.”

After a failed attempt to integrate the school following the landmark Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education, Bordentown was forced to close its doors. Grant relocated to New York City, where she taught English and Latin at the private Ethical Culture Fieldston School for nearly a decade.

Open and scroll to read the article transcript

[top left corner, handwritten in pencil] 974.905

[slightly above and across the left end of the headline, smudged ink stamp] NEW JERSEY STATE LIBRARY

THE IRONSIDES ECHO

PUBLISHED IN THE INTEREST OF THE BORDENTOWN MANUAL TRAINING SCHOOL

[double-line horizontal divider]

Volume XXIII BORDENTOWN, N. J., MAY-JUNE,1939 No. 8

[double-line horizontal divider]

[to the right of the masthead, stamped diagonally in ink]

PROPERTY OF

[horizontal line divider]

RECEIVED

JUN 15 1939

NEW JERSEY STATE LIBRARY

TRENTON

[across columns 1–2]

BORDENTOWN SINGS FOR ALBERT EINSTEIN AND THOMAS MANN

[column 1]

[horizontal line divider]

Other Celebrities Hear Concert of Spirituals; Work of School Praised

[horizontal line divider]

Saturday, May 20, was a day never to be forgotten by faculty and students on the Bordentown campus; for in the audience of celebrities who listened to a forty-five minute recital of Negro spirituals sung by some four hundred and fifty voices were Albert Einstein, distinguished and world famous scientist, and Thomas Mann, Nobel Prize-winner, and considered by many to be the greatest novelist of all time.

[black and white photograph of, left to right, a woman and two men standing in front of a parked car]

Mrs. Mann, Dr. Mann, and Dr. Einstein on Campus.

[column 2]

[horizontal line divider]

Oranges Score May 30 E. Orange Choir Wins Orange “Y’ Victor

[horizontal line divider]

Decoration Day at Bordentown was a banner day for the Oranges. Calvary Baptist Church of East Orange, captured the Choir Contest for the third time and thereby acquired permanent possession of the trophy.

Members of the Montclair “Y” captured the Inter Y.M.C.A. trophy scoring twenty-seven points with Camden second with twenty points.

Both the choir contest and track meet as well as the girls’ calisthenics and boys’ drill attracted a crowd of some eight thousand visitors who spent the day on the grounds.

In the choir contest there were only three entries, but the singing was so good that the judges had extreme difficulty. Calvary was competing with St. John’s from Newark, and First Baptist from Cranford.

The “Y” meet attracted many visitors and rooters and was handled by many of the well-known track stars of the country. Ben Johnson was official starter; Jim Herbert, Eulace Peacock and James Peacock were among the judges. “Y” official were also in the line-up: Drs. Bell, Sutherland and Yates. Bordentown faculty assisted in person of Major Watson, Messers Ray and Morrow.

Winners were as follows:

100 yard dash: Sadler of Camden, 10:01.

220 yard dash: Cooke of Newark, 21:09.

440 yard dash: Ingram of Newark, 52:04.

880 yard run: Daley of Plainfield, 2:04.

Mile run: Alexander of Orange, […]

[column 3]

Honor Studies Class of 1939

[horizontal line divider]

Joseph Hall

Lawrence Towler

Victor Quinchette

Walter Jacobs

William Walker

[horizontal line divider]

Valedictorian Wins Reader’s Digest Award

[black and white photograph of two young Black men in uniforms]

Lawrence Towler, Salutatorian

Joseph Hall, Valedictorian

[horizontal line divider]

W. R. Valentine, principal of Manual Training High School, announces that the coveted Reader’s Digest Award for Scholastic Achievement has been won by the valedic- […]

[across columns 4–5]

MARY McLEOD BETHUNE TO DELIVER COMMENCEMENT ADDRESS

[column 4]

[horizontal line divider]

Tentative List of Graduates

[horizontal line divider]

The following tentative list is of students who, having successfully completed all their work, are candidates for diplomas and certificates on June 15.

GIRLS

Allison, Anna

Anderson, Joy

Baugh, Julia

Buffalo, Victoria

Buntin, Mary

Butler, Lillian

Carter, Catherine

Dunlap, Bertha

Ellis, Alberta

Grogan, Mary

Hendricks, Ruth

Ivery, Doretha

Jackson, Anna

Lee, Naomi

Lewis, Eleanor

Nichols, Jacqueline

Olton, Vivian

Percy, France

Roberts, Sadie

Scott, Elizabeth

Smith, Eulalie

Smith, Ruth

Thomas, Minnie

Thomas, Juanita

Tucker, Beatrice

Tyler, Edith

Ware, Julia

Weaver, Miriam

BOYS

Allison, Theodore

Atterbeary, Knowlton

Bush, William

Chamberlain, Solon

Ralph Crawford

Dingus, Charles

Hall, Joseph

Hamlett, William […]

[column 5]

[horizontal line divider]

Rev. Louis Berry Of Newark Preaches Annual Sermon

[horizontal line divider]

The announcement tentatively made sometime ago, that Mary McLeod Bethune, Director, Division of Negro Affairs, National Youth Administration, would deliver the commencement address has been confirmed and is now made officially. Mrs. Bethune, who addressed a commencement audience at Bordentown before she was appointed to her Youth Administration post, has

[horizontal line divider]

[black and white photograph of three young Black men in uniforms and two young Black women in dresses and dress coats]

[…]

[end of page excerpt]

Determined to instill in her students an awareness of Black achievement, Grant regularly invited prominent Black people to speak at Bordentown. The front page of the May–June 1939 edition of The Ironsides Echo — the award-winning student newspaper that Grant founded — announced that pioneering Black educator and philanthropist Mary McLeod Bethune would be the Commencement Speaker. Another article celebrated the school choir’s recent performance for celebrities including Albert Einstein./New Jersey State Library (Public Domain)

Grant was a dedicated teacher for over 50 years. At a 1975 testimonial dinner in her honor, one student recalled of being taught by her that it “went beyond anything you could ever hope for in […] the student teacher relationship.” “Portrait of Frances Grant.” Circa 1950s/Schlesinger Library

Later Life and Radcliffe Honors

Grant’s teaching career spanned 50 years. She had strong relationships with her students and was honored with a testimonial dinner in 1975. Describing Grant’s approach to teaching, one of her former students — who was also a participant in the Black Women’s Oral History Project — said,

Miss Grant taught English literature. It went beyond anything that you could ever hope for in … the student teacher relationship… Every year Miss Grant spent the summer in Europe and every summer she came back and opened a whole new world. Poetry had meaning. Medieval architecture had meaning.

In recognition of her life of service as an educator, Grant was one of 10 women honored by Radcliffe College in 1979 with a Centennial Alumnae Recognition Award.

She died in 1982, and was buried alongside her parents at Mount Pleasant Cemetery in Arlington, Massachusetts, near her childhood summer home.

Selected Sources

Bordentown Manual Training School Photographs, ca. 1930s–1950s. New Jersey State Archives. Trenton, NJ.

“Dr. George Franklin Grant (1846–1910): Pioneering Dentist, Teacher, Inventor.” Harvard School of Dental Medicine, n. d.

Frances Grant (1895-1982), New York, New York. Interviewed by: Maurine P. Rothschild, October 7, 8, 15, and 21, 1977. Interviews of the Black Women Oral History Project, 1976-1981, OH-31: T-32. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute.

Jacobberger, Margaret L. “Frances Olivia Grant.” In Black Women in America, 2nd edition. Edited by Darlene Clark Hine. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2005.

“Documentary Focuses On ‘Tuskegee of the North’.” Dave Davidson and Clement Price interviewed by Allison Keyes. Tell Me More. NPR, May 24, 2010.

More profiles

Eva B. Dykes

Eva Beatrice Dykes made history at Radcliffe College in 1921 as the first Black woman to complete the requirements for a Ph.D. in the United States.

Marita Bonner

Marita Bonner Occomy, an award-winning author and song writer who published under her maiden name Marita Bonner, graduated from Radcliffe College in 1922.

Caroline Bond Day

Caroline Bond Day earned her A.M. in anthropology in 1930, making her one of the first African Americans to earn a graduate degree from Radcliffe College. Her work in anthropology directly challenged the racial hierarchies…