Clement G. Morgan

Class of 1893

Clement G. Morgan

In 1893, Clement Garnett Morgan became the first Black student to have graduated from both Harvard College and Harvard Law School. He went on to make history as the first Black alderman in New England and as a founding member of the Niagara Movement, the predecessor of the NAACP.

School: Harvard College, Harvard Law School

Degree: A.B., LL.B.

Area of Impact: Law, Public Service

A Scholar and a Speaker

Clement Morgan was born enslaved in Stafford County, Virginia, in January 1859. After he and his family were emancipated during the Civil War, they moved to Washington, D.C., where he attended M Street High School. After graduation he worked for a time as a barber, and later moved to St. Louis, Missouri, where he taught at the all-Black Charles Sumner High School.

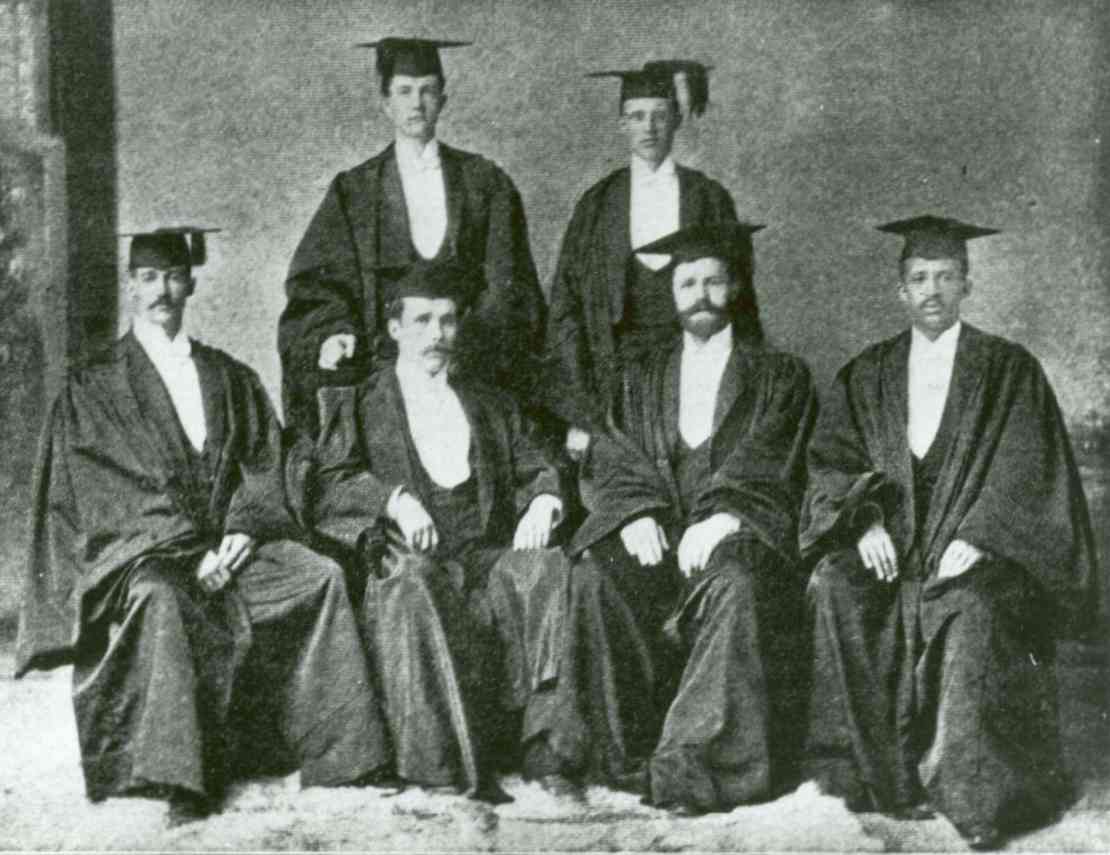

In his mid-twenties, Morgan moved to Boston to attend the Boston Latin School. He earned the prestigious Franklin Medal, as well as won the 1st and 3rd Lawrence Prizes for declamation and reading. After graduating with honors in 1886, he enrolled in Harvard College. For two years, until W.E.B. Du Bois (A.B. 1890, A.M. 1891, Ph.D. 1895) enrolled in 1888, he was the only Black student on campus. Like other early Black students of Harvard and Radcliffe, he did not live on campus — a newspaper profile published in late 1889 noted that he lived with a Black family in Cambridgeport, “an unfashionable neighborhood at a distance of about a mile and half from Harvard.” Morgan received some academic scholarships, but not enough to fully support him; he earned additional money by working as a barber and giving readings and speeches at summer resorts. In 1889, he won the Boylston Prize for oratory at Harvard. Notably, Du Bois finished second.

Morgan was the first Black person to deliver Harvard’s senior class oration. But when both Morgan and Du Bois were selected as Commencement speakers — a separate honor — a faculty member moved to consult the Harvard Corporation as to whether two Black students should have such an honor. The Corporation decided against it: Du Bois spoke, Morgan did not.

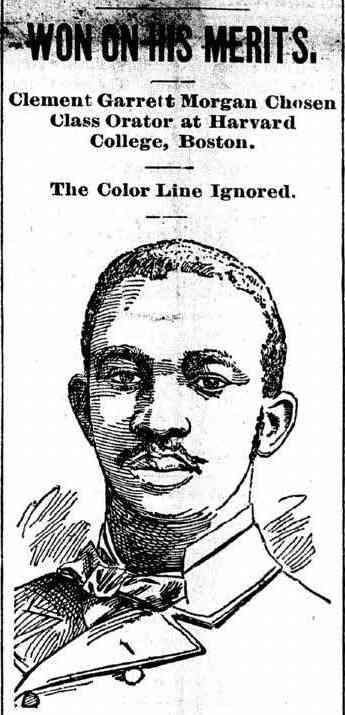

Morgan was selected to deliver Harvard’s senior class oration for the class of 1890 — the first Black person to receive that honor. “WON ON HIS MERITS. Clement Garrett Morgan Chosen Class Orator at Harvard College, Boston. The Color Line Ignored.” The Appeal. St. Paul, Minnesota; Minneapolis, Minnesota; Chicago, Illinois. Oct. 26, 1889/Public Domain

Open and scroll to read the article transcript

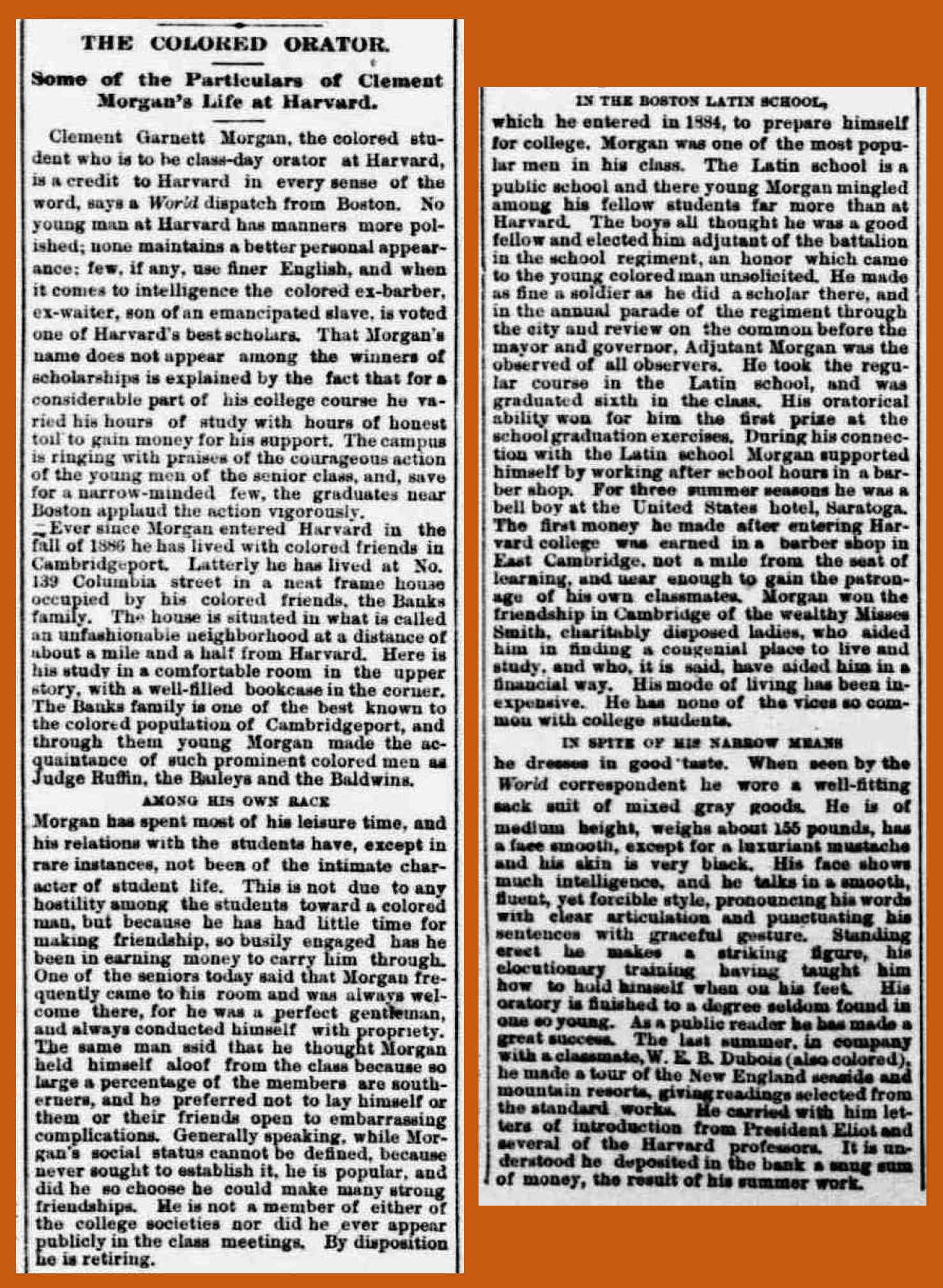

THE COLORED ORATOR.

Some of the Particulars of Clement Morgan’s Life at Harvard University.

Clement Garnett Morgan, the colored student who is to be class-day orator at Harvard, is a credit to Harvard in every sense of the word, says a World dispatch from Boston. No young man at Harvard has manners more polished; none maintains a better personal appearance; few, if any, use finer English, and when it comes to intelligence the colored ex-barber, ex-waiter, son of an emancipated slave, is voted one of Harvard’s best scholars. That Morgan’s name does not appear among the winners of scholarships is explained by the fact that for a considerable part of his college course he varied his hours of study with hours of honest toil to gain money for his support. The campus is ringing with praises of the courageous action of the young men of the senior class, and, save for a narrow-minded few, the graduates near Boston applaud the action vigorously.

Ever since Morgan entered Harvard in the fall of 1886 he has lived with colored friends in Cambridgeport. Latterly he has lived at 139 Columbia street in a neat frame house occupied by his colored friends, the Banks family. The house is situated in what is called an unfashionable neighborhood at a distance of about a mile and half from Harvard. Here is his study in a comfortable room in the upper story, with a well-filled bookcase in the corner. The Banks family is one of the best known to the colored population of Cambridgeport, and through them young Morgan made the acquaintance of such prominent men as Judge Ruffin, the Baileys and the Baldwins.

AMONG HIS OWN RACE

Morgan has spent most of his leisure time, and his relations with the students have, except in rare instances, not been of the intimate character of student life. This is not due to any hostility among the students toward a colored man, but because he has had little time for making friendship, so busily engaged has been in earning money to carry him through. One of the seniors today said that Morgan frequently came to his room and was always welcome there, for he was a perfect gentleman, and always conducted himself with propriety. The same man asid that he thought Morgan held himself aloof from the class because so large a percentage of the members are southerners, and he preferred not to lay himself or them or their friends open to embarrassing complications. Generally speaking, while Morgan’s social status cannot be defined, because he never sought to establish it, he is popular, and did he so choose he could make many strong friendships. He is not a member of either of the college societies nor did he ever appear publicly in the class meetings. By disposition he is retiring.

IN THE BOSTON LATIN SCHOOL,

which he entered in 1884, to prepare himself for college, Morgan was one of the most popular men in his class. The Latin school is a public school and there young Morgan mingled among his fellow students far more than at Harvard. The boys all though was a good fellow and elected him adjutant of the battalion in the school regiment, an honor which came to the young colored man unsolicited. He made as fine a soldier as he did a scholar there, and in the annual parade of the regiment through the city and review on the common before the mayor and governor, Adjutant Morgan was the observed of all observers. He took the regular course in the Latin school, and was graduated sixth in the class. His oratorical ability won for him the first prize at the school graduation exercises. During his connection with the Latin school Morgan supported himself by working after school hours in a barber shop. For three summer seasons he was a bell boy at the United States hotel, Saratoga. The first money he made after entering Harvard college was earned in a barber shop in East Cambridge, not a mile from the seat of learning, and near enough to gain the patronage of his own classmates. Morgan won the friendship in Cambridge of the wealthy Misses Smith, charitably disposed ladies, who aided him in finding a congenial place to live and study, and who, it is said, have aided him in a financial way. His mode of living has been inexpensive. He has none of the vices so common with college students.

IN SPITE OF HIS NARROW MEANS

he dresses in good taste. When seen by the World correspondent he wore a well-fitting sack suit of mixed gray goods. He is of medium height, weighs about 155 pounds, has a face smooth, except for a luxuriant mustache and his skin is very black. His face shows much intelligence, and he talks in a smooth, fluent, yet forcible style, pronouncing his words with clear articulation and punctuating his sentences with graceful gesture. Standing erect he makes a striking figure, his elocutionary training having taught him how to hold himself when on his feet. His oratory is finished to a degree seldom found in one so young. As a public reader he has made a great success. The last summer, in company with a classmate, W. E. B. Dubois (also colored), he made a tour of the new England seaside and mountain resorts, giving readings selected from the standard works. He carried with him letters of introduction from President Eliot and several of the Harvard professors. It is understood he deposited in the bank a snug sum of money, the result of his summer work.

[end of article]

Morgan’s achievement in being selected as the class day orator was covered by white-owned newspapers across the United States. The Evening Star in Washington, DC, described him as “a credit to Harvard in every sense of the word.” “The Colored Orator: Some of the Particulars of Clement Morgan’s Life at Harvard.” October 22, 1889/Public Domain

A Leader in the Fight for Equality

Morgan entered Harvard Law School in 1890 and received his LL.B. in 1893, becoming the first Black student to earn degrees from both Harvard College and Harvard Law School. After graduation, he passed the bar and established a law office in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

While practicing law, Morgan began a career in politics. He served on the Cambridge Common Council in 1895 and 1896 and the Cambridge Board of Aldermen from 1897 to 1899, making him the first Black alderman in New England.

His political successes were limited, however: he ran unsuccessfully for the Massachusetts legislature in 1899, 1900, and 1908.

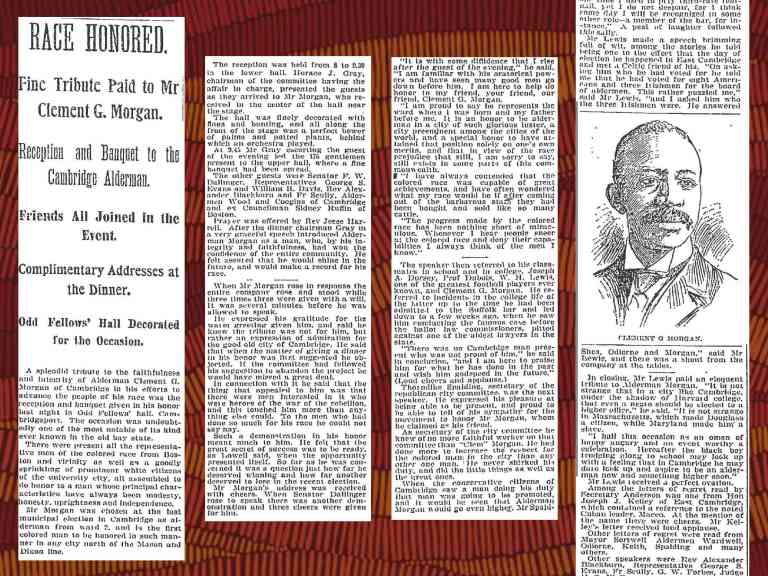

Shortly after he was elected the first Black alderman in New England history, Morgan was honored with a celebratory dinner in Cambridge, where he was praised by fellow politicians and Harvard graduates — both Black and white. “Race Honored: Fine Tribute Paid to Mr. Clement G. Morgan….” January 22, 1897/Public Domain

Open and scroll to read the article transcript

[newsprint article broken over four columns, cut from original page and displayed on a patterned background; spelling and typographical errors preserved; formatting preserved wherever possible]

RACE HONORED.

Fine Tribute Paid to Mr. Clement G. Morgan.

Reception and Banquet to the Cambridge Alderman.

Friends All Joined the Event.

Complimentary Address at the Dinner.

Odd Fellows’ Hall Decorated for the Occasion.

A splendid tribute to the faithfulness and integrity of Alderman Clement G. Morgan of Cambridge in his efforts to advance the people of his race was the reception and banquet given in his honor last night in Odd Fellows’ hall, Cambridgeport. The occasion was undoubtedly one of the most notable of its kind ever known in the old bay state.

There were present all the representative men of the colored race from Boston and vicinity as well as a goodly sprinkling of prominent white citizens of the university city, all assembled to do honor to a man whose principal characteristics have always been modesty, honesty, uprightness and independence.

Mr Morgan was chosen at the last municipal election in Cambridge as alderman from ward 2, and is the first colored man to be honored in such manner in any city north of the Mason and Dixon line.

The reception was held from 8 to 9.30 in the lower hall. Horace J. Gray, chairman of the committee having the affair in charge, presented the guests as they arrived to Mr Morgan, who received in the center of the hall near the stage.

The hall was finely decorated with flags and bunting, and all along the front of the stage was a perfect bower of palms and potted plants, behind which an orchestra played.

At 9.45 Mr Gray escorting the guest of the evening led the 175 gentlemen present to the upper hall, where a fine banquet had been spread.

The other guests were Senator F. W. Dallinger, Representatives George S. Evans and William R. Davis, Rev Alexander Blackburn and Fr Scully, Aldermen Wood and Coogins of Cambridge and ex Councilman Sidney Ruffin of Boston.

Prayer was offered by Rev Jesse Harrell. After the dinner chairman Gray in a very graceful speech introduced Alderman Morgan as a man, who, by his integrity and faithfulness, had won the confidence of the entire community. He felt assured that he would shine in the future, and would make a record for his race.

[horizontal dividing line]

When Mr. Morgan rose in response the entire company rose and stood while three times three were given with a will. It was several minutes before he was allowed to speak.

He expressed his gratitude for he warm greeting given him, and said he knew the tribute was not for him, but rather an expression of admiration for the good old city of Cambridge. He said that when the matter of giving a dinner in his honor was first suggested he objected. If the committee had followed his suggestion to abandon the project he would have missed a great deal.

In connection with it he said that the thing that appealed to him was that there were men interested in it who were heroes of the war of the rebellion, and this touched him more than anything else could. To the men who had done so much for his race he could not say nay.

Such a demonstration in his honor meant much to him. He felt that the great secret of success was to be ready, as Lowell said, when the opportunity presented itself. So far as he was concerned it was a question just how far he deserved winning and how far another deserved to lose in the recent election.

Mr Morgan’s address was received with cheers. When Senator Dallinger rose to speak there was another demonstration and three cheers were given for him.

“It is with some diffidence that I rise after the guest of the evening,” he said. “I am familiar with his oratorical powers and have seen many good men go down before him. I am here to help do honor to my friend, your friend, our friend, Clement G. Morgan.

“I am proud to say he represents the ward where I was born and my father before me. It is an honor to be alderman in a city of such glorious luster, a city preeminent among the cities of the world, and a special honor to have attained that position solely on one’s own merits, and that in view of the race prejudice that still, I am sorry to say, still exists in some parts of this commonwealth.

“I have always contended that the colored race was capable of great achievements, and have often wondered what my race would be if after coming out of the barbarous state they had been bought and sold like so many cattle.

“The progress made by the colored race has been nothing short of miraculous. Whenever I hear people sneer at the colored race and deny their capabilities I always think of the men I know.”

[horizontal dividing line]

The speaker then referred to his classmates in school and in college, Joseph A. Dorsey, Prof Dubois, W. H. Lewis, one of the greatest football players ever known, and Clement G. Morgan. He referred to incidents in the college life of the latter up to the time he had been admitted to the Suffolk bar and led down to a few weeks ago, when he saw him conducting the famous case before the ballot law commissioners, pitted against one of the ablest lawyers in the state.

“There was no Cambridge man present who was not proud of him,” he said in conclusion, “and I am here to praise him for what he has done in the past and wish him godspeed in the future.” (Loud cheers and applause.)

Thorndike Spalding, secretary of the republican city committee, was the next speaker. He expressed his pleasure at being able to be present, and proud to be able to tell of his sympathy for the movement to honor Mr Morgan, whom he claimed as his friend.

As secretary of the city committee he knew of no more faithful worker on that committee than “Clem” Morgan. He had done more to increase the respect for the colored man in the city than any other one man. He never shirked his duty, and did the little things as well as the great ones.

When the conservative citizens of Cambridge saw a man doing his duty that man was going to be promoted, and it would be seen that Alderman Morgan would go even higher. Mr Spalding’s prediction was cheered to the echo.

William H. Lewis, the famous football player, when introduced said: “I’ve been introduced as a football player because one time I used to play third-rate football, yet I do not despair, for I think some day I will be recognized in some other role — a member of the bar, for instance.” A peal of laughter followed this sally.

Mr Lewis made a speech brimming full of wit, among the stories he told being one to the effect that the day of election he happened in East Cambridge and met a Celtic friend of his. “On asking him who he had voted for he told me that he had voted for either Americans and three Irishmen for the board of aldermen. This rather puzzled me,” said Mr Lewis, “and I asked who the three Irishmen were. He answered

[horizontal dividing line]

[line drawing of a bust portrait of Clement Morgan]

[image caption] CLEMENT G. MORGAN

[horizontal dividing line]

Shea, Odiorne and Morgan,” said Mr Lewis, and there was a shout from the company at the tables.

[horizontal dividing line]

In closing, Mr Lewis paid an eloquent tribute to Alderman Morgan. “It is not strange that in a city like Cambridge, under the shadow of Harvard college, that even a negro should be elected to a higher office,” he said. “It is not strange in Massachusetts, which made Douglass a citizen, while Maryland made him a slave.

“I hail this occasion as an omen of happy augury and an event worthy a celebration. Hereafter the black boy trudging along to school may look up with a feeling that in Cambridge he may dare look up and aspire to be an alderman now and something higher soon.”

Mr Lewis received a perfect ovation.

Among the letters of regret read by Secretary Anderson was one from Hon Joseph J. Kelley of East Cambridge, which contained a reference to the noted Cuban leader, Macco. At the mention of the name there were cheers. Mr Kelley’s letter received loud applause.

Other letters of regret were read from Mayor Sortwell Aldermen Wardwell, Odiorne, Keith, Spalding and many others.

[end of article]

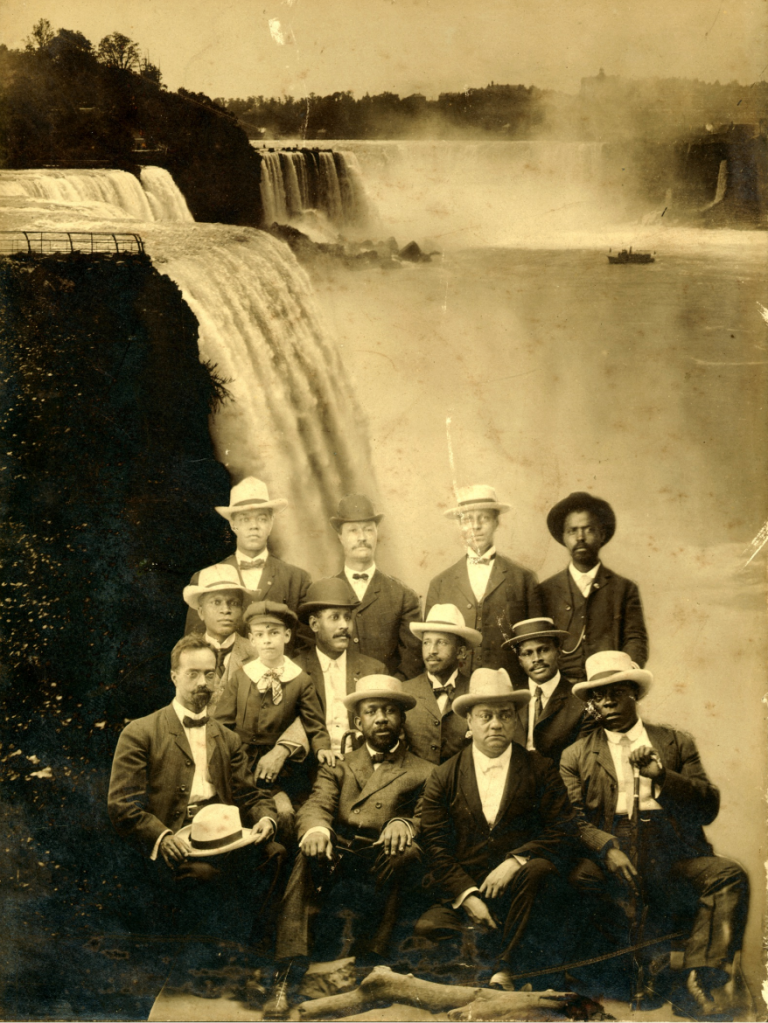

Gertrude Wright Morgan (seated) was a founding member, alongside her husband, of the Niagara Movement in 1905. She is pictured here at the 1906 meeting at the historically Black Storer College in Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia, where women gained full membership in the organization./Public domain via West Virginia History OnView

In the same period, Morgan became part of a group calling themselves the Negro Radicals. Comprised of prominent Black intellectuals, attorneys, and activists, including Butler R. Wilson, Archibald Henry Grimké (LL.B. 1874), George Forbes, and William Monroe Trotter (A.B. 1895, A.M. 1896), the group publicly opposed Tuskegee Institute leader Booker T. Washington’s politics of accommodation, advocating instead for full and immediate civil rights for Black people.

Also during this period, in 1897, Morgan married teacher Gertrude Wright, whom he had met during his time in St. Louis. Gertrude Morgan went onto become a recognized activist in her own right, fighting for civil rights and women’s suffrage.

In 1905, the Morgans were two of the founding members of the Niagara Movement, initially convened by Du Bois and Trotter. The Movement — forerunner to the NAACP — was also concerned with opposing Washington’s philosophy of accommodation. The Movement’s “Declaration of Principles” stated:

We refuse to allow the impression to remain that the Negro-American assents to inferiority, is submissive under oppression and apologetic before insults.

The Movement sought equal rights for Black Americans, economic and educational opportunities, and the right to vote.

In 1910, Morgan joined the newly formed NAACP, serving on the executive committee of the Boston branch from 1912 to 1914. He continued his law practice in Boston and remained active in local civil rights work. In 1915 and 1921, he led efforts to stop the racist film The Birth of a Nation from being shown in the Boston area.

Open and scroll to read the article transcript

[one-column newsprint article; spelling and typographical errors preserved; formatting preserved wherever possible]

WILL FIGHT HARD.

Clement G. Morgan for Rogers’ Defence.

Doesen’t Want Southern Officers to Repeat Fugitive Slave Experiences.

Claims Rogers Will Surely be Lynched if Sent to NorthCarolina.

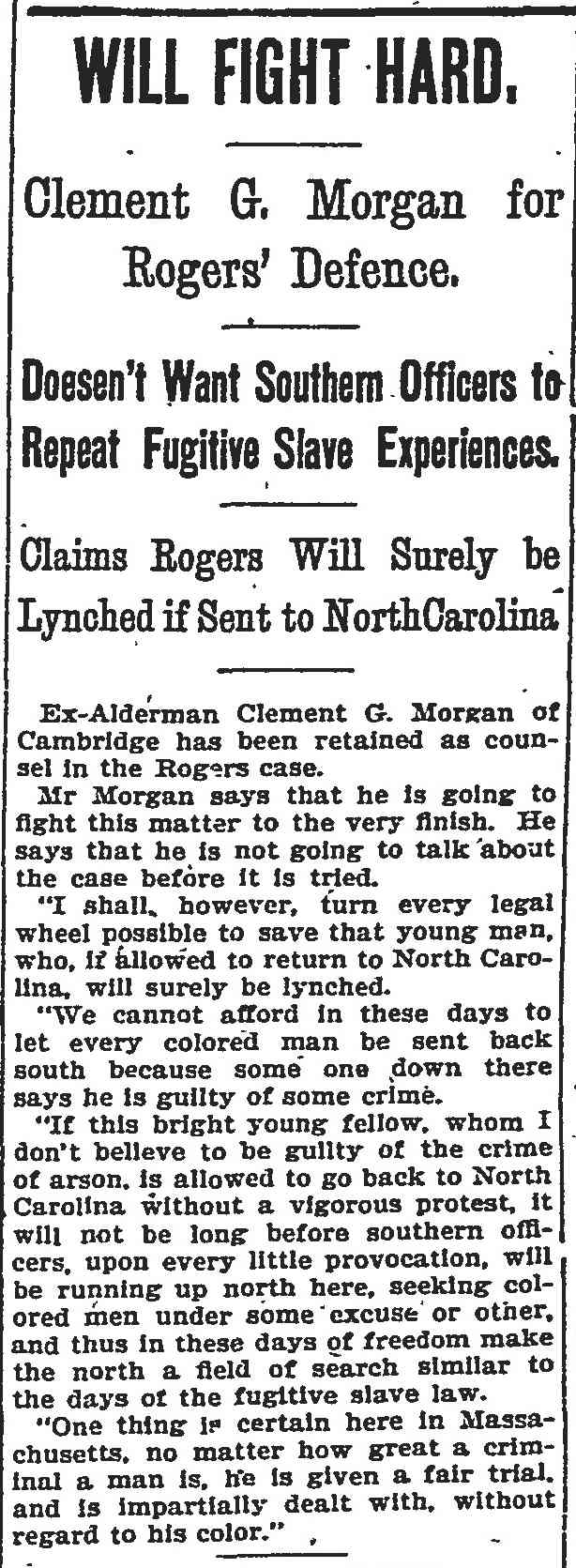

Ex-Alderman Clement G. Morgan of Cambridge has been retained as counsel in the Rogers case.

Mr Morgan says that he is going to fight this matter to the very finish. He says that he is not going to talk about the case before it is tried.

“I shall, however, turn every legal wheel possible to save that young man, who, if allowed to return to North Carolina, will surely be lynched.

“We cannot afford in these days to let every colored man be sent back south because some one down there says he is guilty of some crime.

“If this bright young fellow, whom I don’t believe to be guilty of the crime of arson, is allowed to go back to North Carolina without a vigorous protest, it will not be long before southern officers, upon every little provocation, will be running up north here, seeking colored men under excuse or other, and thus in these days of freedom make the north a field of search similar to the days of the fugitive slave law.

“One thing is certain here in Massachusetts, no matter how great a criminal a man is, he is given a fair trial, and is impartially dealt with, without regard to his color.”

[end of article]

After leaving the Cambridge Board of Alderman Morgan returned to his law practice, where he used the courts to fight for equality. “Will Fight Hard: Clement G. Morgan for Rogers’ Defence….” Boston Daily Globe. Boston, MA. August 5, 1902/Public Domain

Open and scroll to read the article transcript

[one-column newsprint article; spelling and typographical errors preserved; formatting preserved wherever possible]

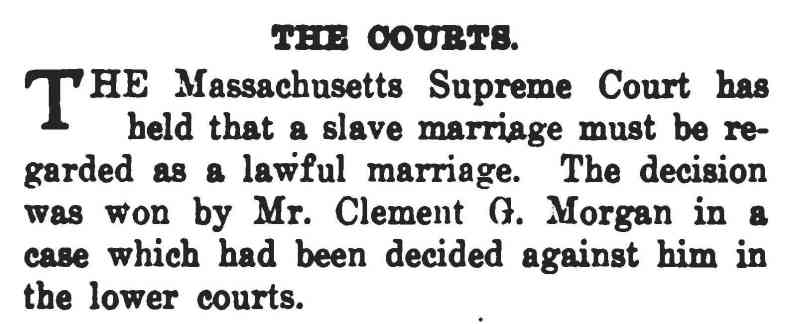

THE COURTS.

THE Massachusetts Supreme Court has held that a slave marriage must be regarded as a lawful marriage. The decision was won by Mr. Clement G. Morgan in a case which had been decided against him in the lower courts.

[end of article]

The Crisis — the national magazine of the NAACP — reported May 1913 that Morgan won a case before the Massachusetts Supreme Court that held that marriages between enslaved people must be regarded as lawful. “Along the Color Line: The Courts.” The Crisis Vol. 6, No. 1. May 1913/Public Domain

Open and scroll to read the article transcript

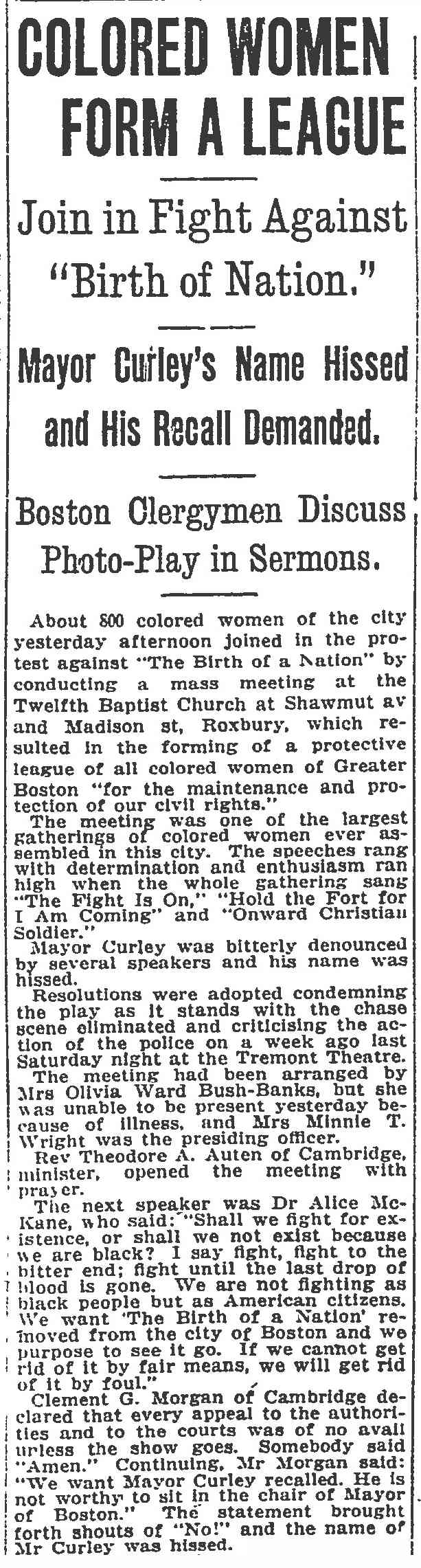

COLORED WOMEN FORM A LEAGUE

Join in Fight Against “Birth of Nation.”

Mayor Curley’s Name Hissed and His recall Demanded.

Boston Clergymen Discuss Photo-Play in Sermons.

About 800 colored women of the city yesterday afternoon joined in the protest against “The Birth of a Nation” by conducting a mass meeting at the Twelfth Baptist Church at Shawmut av and Madison st, Roxbury, which resulted in the forming of a protective league of all colored women of Greater Boston “for the maintenance and protection of our civil rights.”

The meeting was one of the largest gatherings of colored women ever assembled in this city. The speeches rang with determination and enthusiasm ran high when the whole gathering sang “The Fight Is On,” “Hold the Fort for I Am Coming” and “Onward Christian Soldier.”

Mayor Curley was bitterly denounced by several speakers and his name was hissed.

Resolutions were adopted condemning the play as it stands with the chase scene eliminated and criticizing the action of the police on a week ago last Saturday night at the Tremont Theatre.

The meeting had been arranged by Mrs Olivia Ward Bush-Banks, but she was unable to be present yesterday because of illness, and Mrs Minnie T. Wright was the presiding officer.

Rev Theodore A. Auten of Cambridge, minister, opened the meeting with prayer.

The next speaker was Dr Alice McKane, who said: “Shall we fight for existence, or shall we not exist because we are black? I say fight, fight to the bitter end; fight until the last drop of blood is gone. We are not fighting as black people but as American citizens. We want “The Birth of a Nation’ removed from the city of Boston and we purpose to see it go. If we cannot get rid of it by fair means, we will get rid of it by foul.”

Clement G. Morgan of Cambridge declared that every appeal to the authorities and to the courts was of no avail unless the show goes. Somebody said “Amen.” Continuing, Mr Morgan said: “We want Mayor Curley recalled. He is not worthy to sit in the chair of Mayor of Boston.” The statement brought forth shouts of “No!” and the name of Mr Curley was hissed.

[end of excerpt]

Morgan joined protests against the showing of the racist film The Birth of a Nation, which celebrated the birth of the Ku Klux Klan and used offensive stereotypes to depict Black characters. “Colored Women Form a League: Join in Fight Against ‘Birth of a Nation.’” The Boston Globe. April 26, 1915/Public Domain

Lasting Memorials

In 1929, Morgan was quietly laid to rest in Mount Auburn Cemetery without a monument to mark his grave. In 2005, the Cambridge African American Heritage Trail — a partnership between the Cambridge African American Historic Alliance and the Cambridge Historic Commission — conducted a ceremony at which a memorial was erected to honor Morgan. It reads: “Lawyer, Cambridge Elected Official, A Founder of the NAACP.” The Cambridge Chronicle called the effort “much-deserved, if belated, attention.”

In subsequent years, the City of Cambridge has honored the Morgans as well, renaming a street for Gertrude and establishing Clement G. Morgan Park near the site of the couple’s longtime home. These spaces stand as permanent, physical reminders of Clement G. Morgan’s trailblazing achievements and of both Morgans’ contributions to the community, and remain a marker of pride for local residents over a century later.

Selected Sources

“Clement G. Morgan.” In Blacks at Harvard: A Documentary History of African-American Experience At Harvard and Radcliffe, ed. Werner Sollors et al. New York, NY: NYU Press, 1993, 59–68.

Friends of Mount Auburn. “Clement Morgan (1859–1929): Lawyer, Local Politician, and Founder of the NAACP.” Mount Auburn Cemetery. February 1, 2013.

Friends of Mount Auburn. “Gertrude Wright Morgan (1861–1931): Suffragist, Civil Rights Activist, and Founder of the NAACP.” Mount Auburn Cemetery. August 1, 2020.

Neal, Anthony. “Clement Garnett Morgan: From slavery to Harvard.” Bay State Banner. July 3, 2012.

Kimball, Bruce A. “‘This Pitiable Rejection of a Great Opportunity’: W. E. B. Du Bois, Clement G. Morgan, and the Harvard University Graduation of 1890.” The Journal of African American History 94, no. 1 (2009): 5–20.

More profiles

W.E.B. Du Bois

W.E.B. Du Bois, the first Black person to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard, used his talent and intellect to pave a path toward racial uplift.

Richard T. Greener

Harvard College’s first Black graduate, Richard T. Greener went on to become the first Black professor at the University of South Carolina and dean of the Howard University School of Law.

Carter G. Woodson

Carter G. Woodson, known as “The Father of Black History,” was the second African American to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard University. He created Negro History Week — the forerunner to Black History Month —…