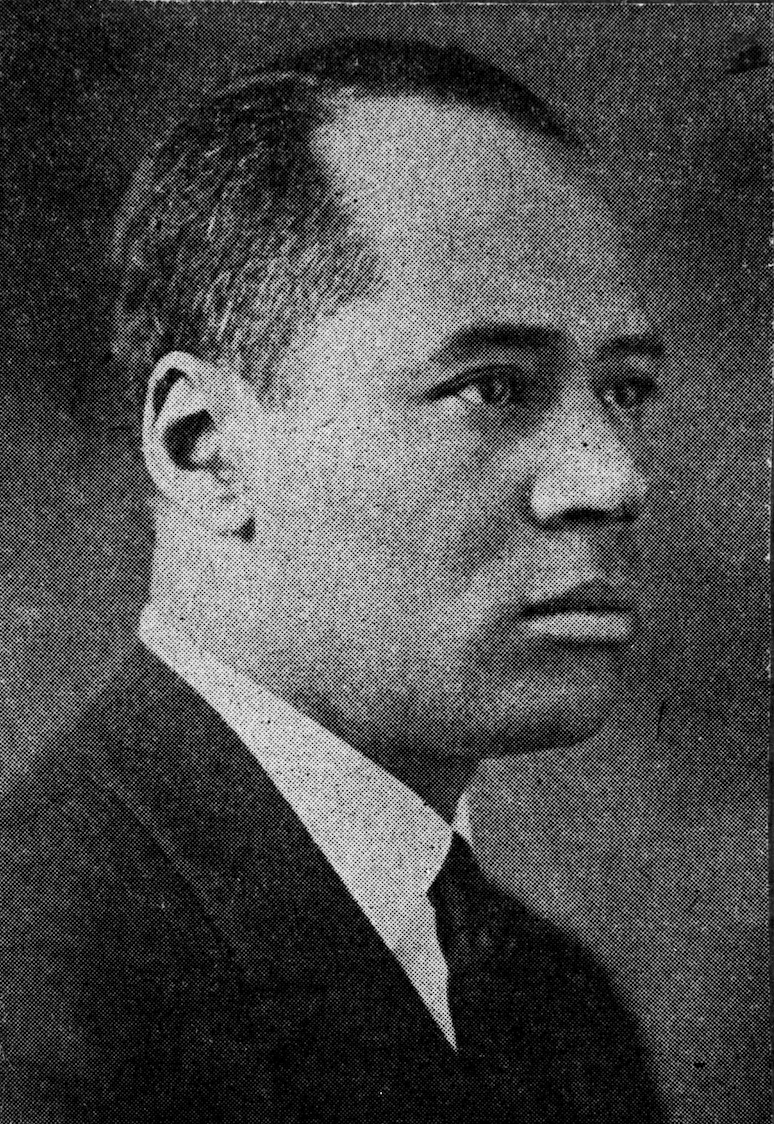

Charles Hamilton Houston

Class of 1923

Charles Hamilton Houston

Known as “The Man Who Killed Jim Crow,” Charles Hamilton Houston was the first Black person to both serve on the Harvard Law Review and earn a Doctor of Juridical Science (S.J.D.) from Harvard Law School.

School: Harvard Law School

Degree: LL.B., S.J.D.

Area of Impact: Law, Civil Rights, Education

HBCU Affiliation: Howard University

An Early Awakening

Born in Washington, DC, in 1895, Houston enrolled in Amherst College in Massachusetts at the age of 16, the only Black student in his class. He earned his bachelor’s degree, magna cum laude, in 1915 and was elected to Phi Beta Kappa. After returning home to teach at Howard University for two years, Houston served in the then-segregated U.S. Army as an officer, including time in France during World War I. Houston would later recall of his service, in a series of essays written in 1940 in the lead up to the United States’ entry into World War II:

The hate and scorn showered on us Negro officers by our fellow Americans […] convinced me that there was no sense in my dying for a world ruled by them. My battleground was America, not France.”

He concluded, “I made up [my mind] that I would never get caught again without knowing something about my rights; that if luck was with me and I got through this war, I would study law and use my time fighting for men who could not strike back.

He was discharged in April 1919, just before the start of the Red Summer — a post-war outbreak of anti-Black violence across the United States that reinforced his determination to fight for equal rights.

When Houston entered Harvard Law School in the fall of 1919 as one of a handful of Black students, he held the fervent belief that integration was key to the social, political, and economic success not just of Black Americans.

Many of the images in this profile are drawn from the collection of Charles Hamilton Houston’s papers, and appear here courtesy of the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center at Howard University.

Preparing to Lead the Fight

Houston flourished at Harvard Law School, earning top grades and a coveted position on the editorial board of the Harvard Law Review — the first Black student to do so, decades before future-US President Barack Obama became the first Black person elected president of the prestigious journal. Houston’s confidence and exemplary work caught the attention of Professor Felix Frankfurter (LL.B. 1906) — later an associate Supreme Court justice — and Dean Roscoe Pound (Hon. LL.D. 1920). He also won the respect of his fellow students, and many of his Black classmates saw him as a leader.

Houston earned a Bachelor of Laws (LL.B.) in 1922 and his Doctor of Juridical Science (S.J.D.) in 1923 — the first year that Harvard awarded the degree, making Houston the school’s first Black S.J.D. graduate. With support from his professors, Houston secured a Sheldon Traveling Fellowship, which he used to continue his studies and earn a Doctor of Civil Laws degree from the University of Madrid.

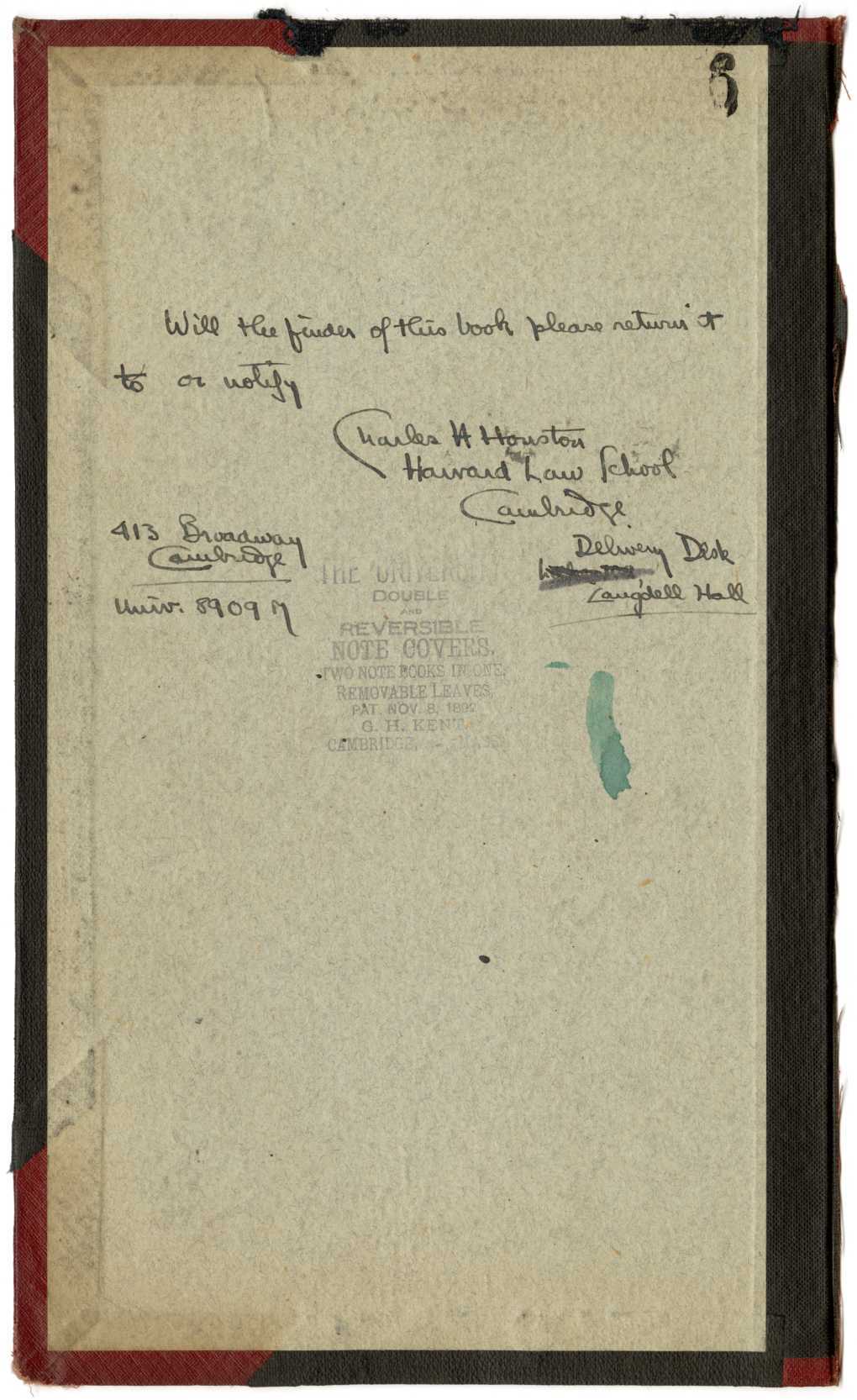

Open and scroll to read the note transcript

[black ink smudge in top right corner]

[handwritten in cursive; first line starts at horizontal center of page]

Will the finder of this book please return it to or notify

Charles H Houston

Harvard Law School

Cambridge

Delivery Desk

[word scribbled out]

[underlined] Langdell Hall

[justified to the left margin]

413 Broadway

[underlined] Cambridge

Univ. 89097

[faded stamp centered on the page]

THE UNIVER[final letters illegible]

DOUBLE

AND

REVERSIBLE

NOTE COVERS.

TWO NOTE BOOKS IN ONE.

REMOVABLE LEAVES.

PAT. NOV. 8, 1892

G. H. KENT

CAMBRIDGE, MASS.

[blue ink smudge to the right of the stamp]

[end of page]

Houston inscribed the cover of one of his notebooks with his personal address at 413 Broadway in Cambridge, as well as instructions to any finder to return it to him via the Delivery Desk at Langdell Hall on the Harvard Law School campus. “Front cover of Harvard Law School Notebook.” Charles Hamilton Houston Papers/Courtesy of the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University Archives

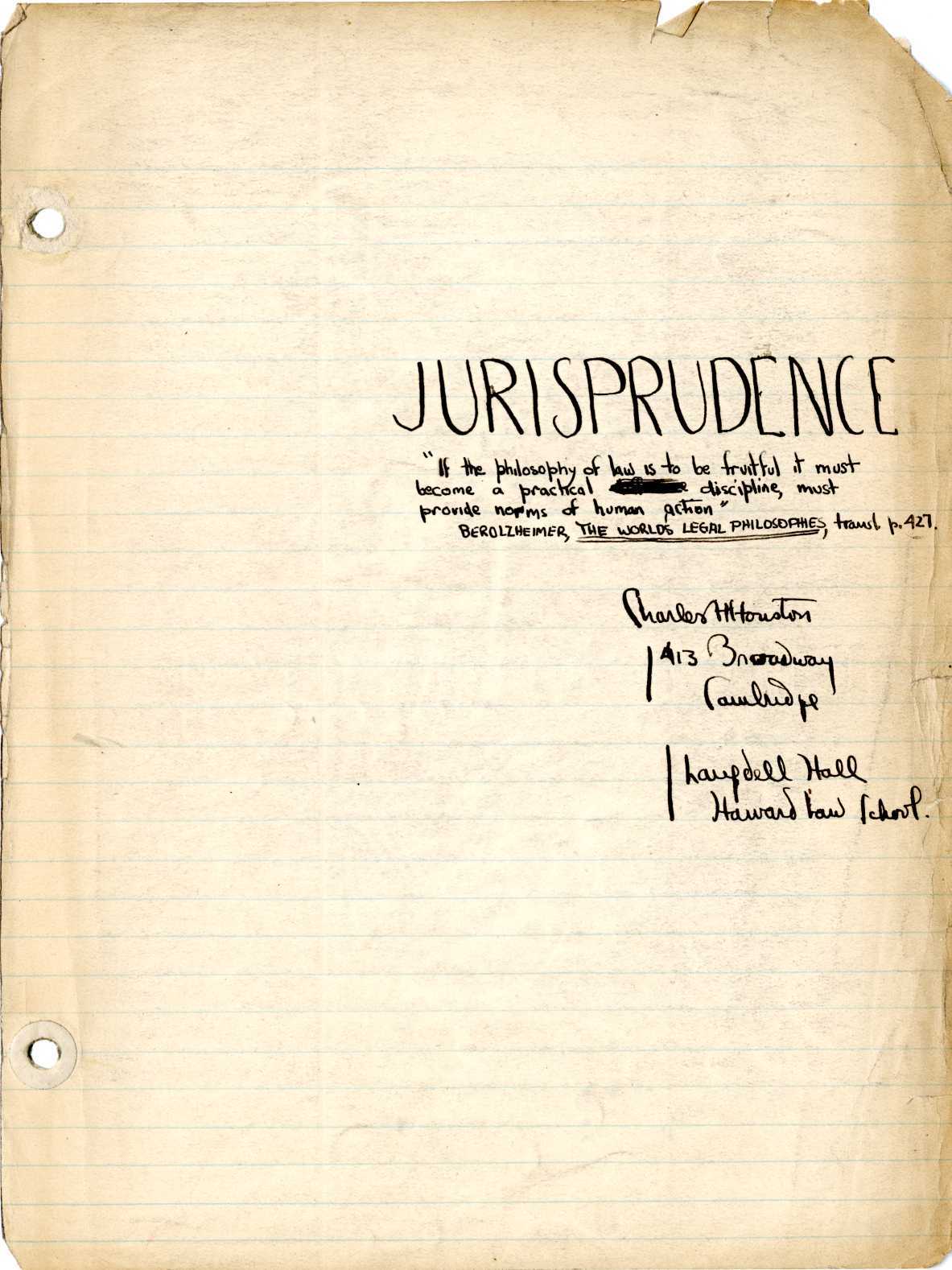

Open and scroll to read the note transcript

[pre-punched holes at the top and bottom of the left margin; edges of the paper are browned, with tearing at the top right corner]

[writing begins one-third of the way down the page and stretches from the center of the page to the right margin]

JURISPRUDENCE

“If the philosophy of law is to be fruitful it must become a practical [word inked out] discipline, must provide norms of human action”

BEROLZHEIMER, [double underline under title] THE WORLD’S LEGAL PHILOSOPHIES, transl p. 427.

[justified to the right margin]

Charles H Houston

413 Broadway

Cambridge

Langdell Hall

Harvard Law School.

[end of page]

On the first page of his notebook for a course at Harvard Law School on “Jurisprudence,” Houston transcribed a quote from the German legal philosopher Fritz Berolzheimer: “If the philosophy of law is to be fruitful it must become a practical discipline, must provide norms of human action.” “Harvard Law School Notebook.” Charles Hamilton Houston Papers/Courtesy of the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University Archives

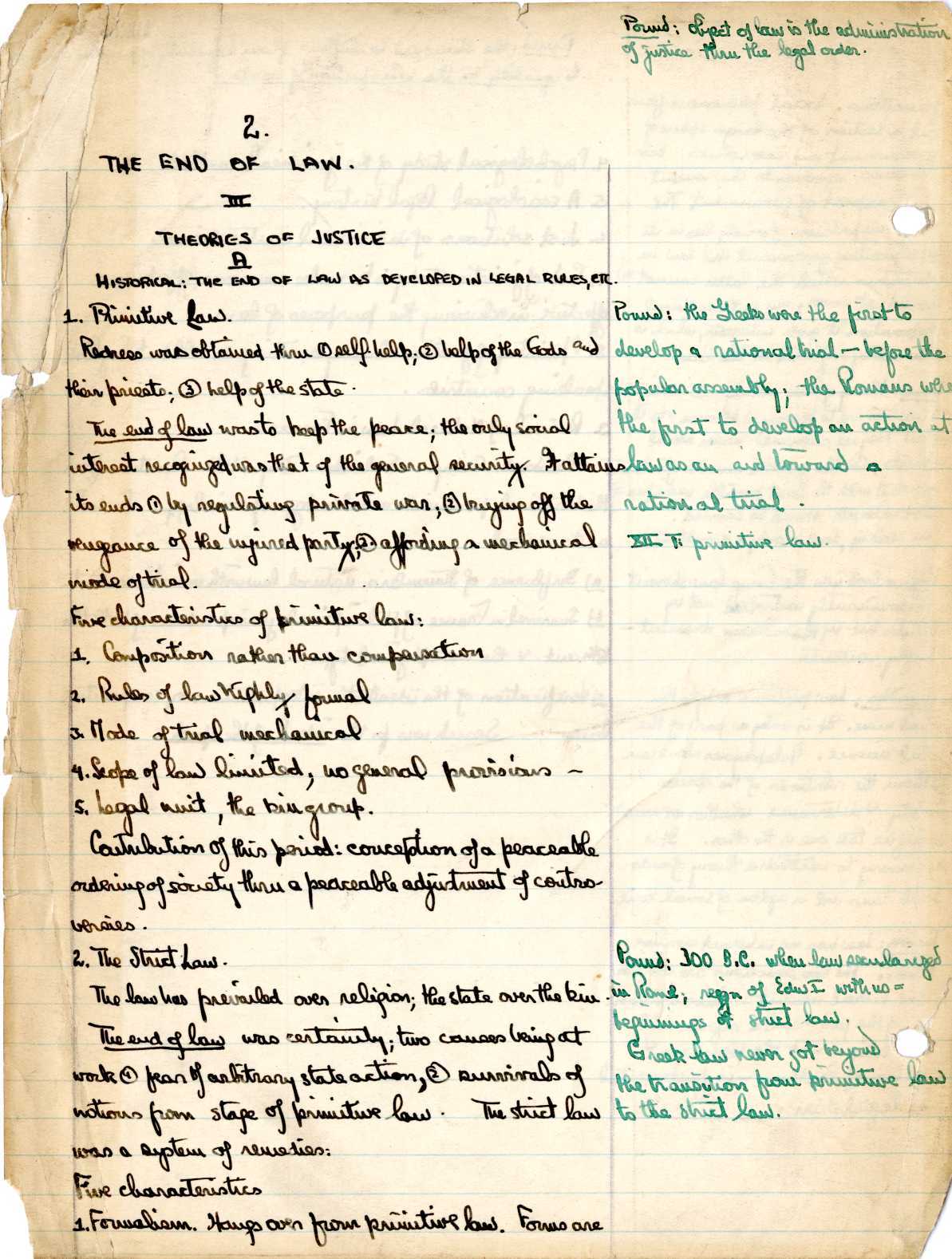

Open and scroll to read the note transcript

[pre-punched holes at the top and bottom of the right margin; edges of the paper are browned, with tearing at the top right corner]

[page divided into two columns by a hand-written vertical line, with a different color ink used in each column; notes on readings are on the left, and notes on Harvard Law School Dean Roscoe Pound’s comments are on the right]

[top right corner] [name underlined] Pound: object of law is the administration of justice thru the legal order.

[slightly lower in left column] 2.

THE END OF LAW.

III

THEORIES OF JUSTICE

[underlined] A

HISTORICAL: THE END OF LAW AS DEVELOPED IN LEGAL RULES, ETC.

1. Primitive Law.

Redress was obtained thru [circled number] 1self help; [circled number] 2 help of the Gods and their priests; [circled number] 3 help of the state.

[underlined] The end of law [end underline] was to keep the peace; the only social interest recognized was that of the general security. [Illegible symbol] attains its ends [circled number] 1 by regulating private war; [circled number] 2 buying off the vengeance of the injured party; [circled number] 3 affording a mechanical mode of trial.

[right column, alongside notes on primitive law and the end of law]

Pound: the Greeks were the first to develop a national trial — before the popular assembly; the Romans were the first to develop an action at law as an aid toward a rational trial.

XII T: primitive law.

[left column, next line]

Five characteristics of primitive law:

1. Composition rather than compensation

2. Rules of law highly formal

3. Mode of trial mechanical

4. Scope of law limited, no general provisions _

5. Legal unit, the kin group.

Contribution of this period: conception of a peaceable ordering of society thru a peaceable adjustment of controversies.

2. The Strict Law.

The law has prevailed over religion; the state over kin.

[underlined] The end of law [end underline] was certainty; two causes being at work [circled number] 1 fear of arbitrary state action, [circled number] 2 survivals of notions from stage of primitive law. The strict law was a system of remedies:

[right column, alongside notes on strict law and the end of law]

Pound: 300 B.C. when law secularized in Rome; reign of EdwI with us = beginnings of strict law.

Greek law never got beyond the transition from primitive law to the strict law.

[left column, next line]

Five characteristics

1. Formalism. Hangs over from primitive law. Forms are

[end of page; end of notebook transcripts]

At the top of a page of meticulous notes on “Theories of Justice,” Houston transcribed comments from instructor and Harvard Law School Dean Roscoe Pound: “object of law is the administration of justice thru the legal order.” “Harvard Law School Notebook.” Charles Hamilton Houston Papers/Courtesy of the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University Archives

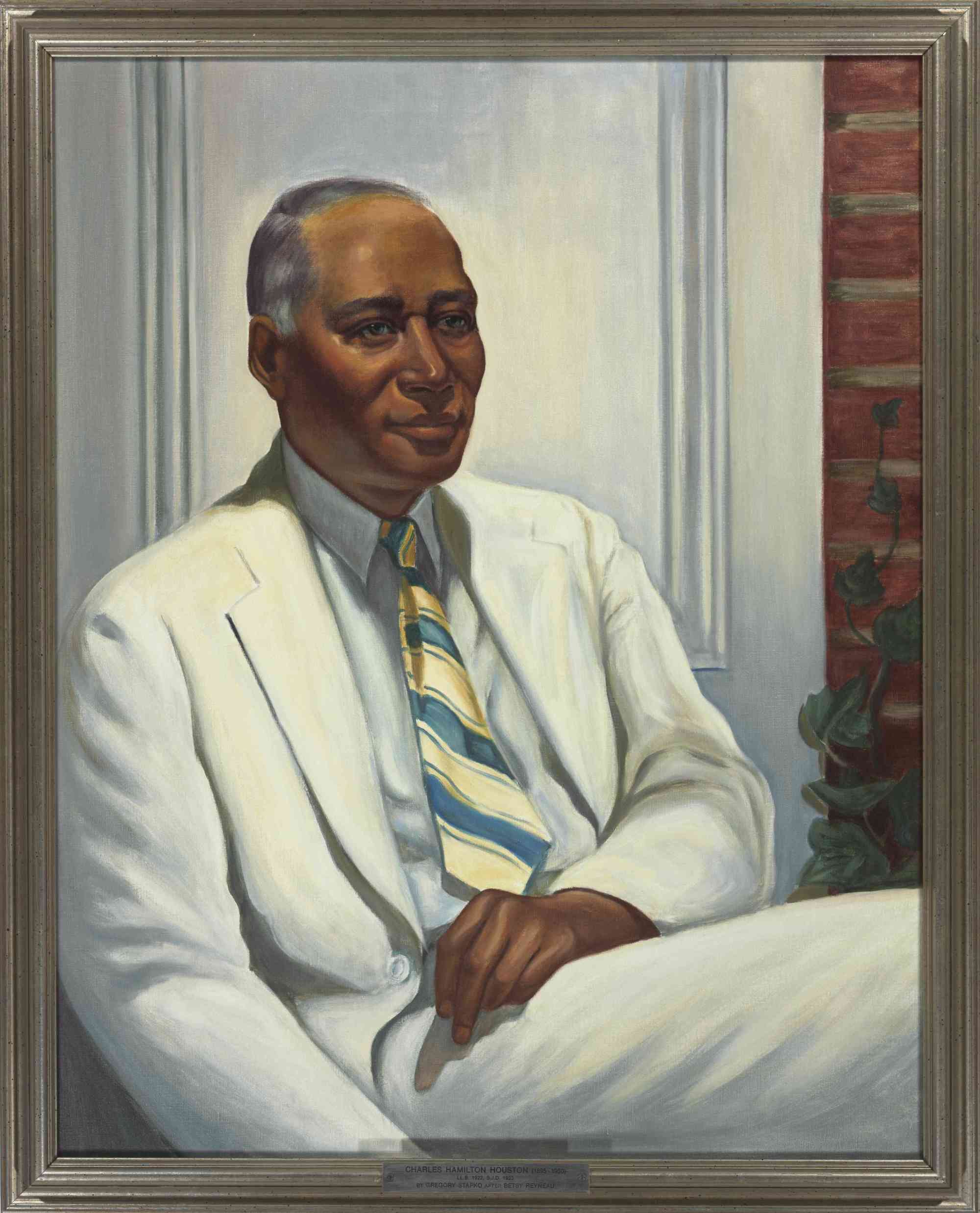

Building a Foundation for the Civil Rights Movement

Houston’s experiences of injustice both at home and abroad prompted him to join his father’s law practice upon his return to Washington, DC. Renamed Houston & Houston, it was one of the first Black law firms established in the district. Houston believed that it was incumbent upon Black lawyers to fight for Black people and Black communities because, he wrote in 1935, “experience has proved that the average white lawyer, especially in the South, cannot be relied upon to wage an uncompromising fight for equal rights for Negroes.” When the American Bar Association refused admission to Black lawyers, Houston and others founded the Washington, DC-based National Bar Association for Black attorneys.

He also taught part-time at Howard Law School during this period. In 1929, Howard’s first Black president, Mordecai Johnson, appointed Houston to serve as the law school’s vice-dean in name, while in fact he fulfilled many of the responsibilities of dean. Houston led the Howard Law School’s transformation from an unaccredited part-time evening program into what legal scholar and former Director-Counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund Jack Greenberg later described as the “West Point of civil rights training.”

Houston’s protégés at Howard included a litany of future civil rights heroes, including Thurgood Marshall, who would later found the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund and become the first Black justice of the United States Supreme Court, and Oliver W. Hill, who worked with Marshall to win the historic case of Brown v. Board of Education that made segregated, “separate but equal” schools unlawful. Their success was not only a matter of rigorous training from Houston; the Brown victory was also built upon legal foundations laid out by Houston in his own successfully argued cases.

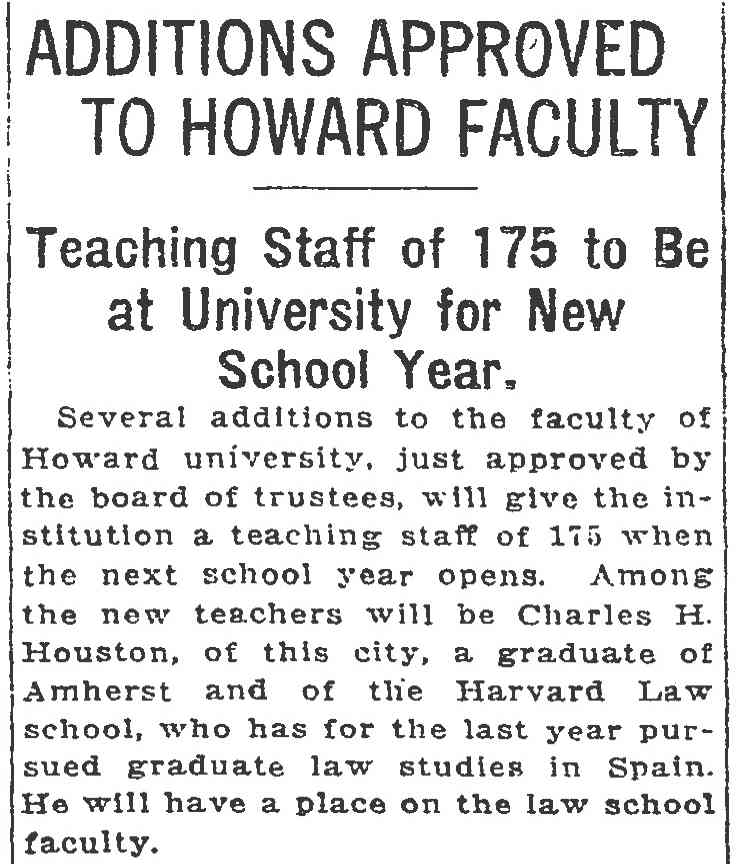

Open and scroll to read the article transcript

[single column newsprint article; spelling and typographical errors preserved; formatting preserved wherever possible]

ADDITIONS APPROVED TO HOWARD FACULTY

[horizontal dividing line]

Teaching Staff of 175 to Be at University for New School Year.

Several additions to the faculty of Howard university, just approved by the board of trustees, will give the institution a teaching staff of 175 when the next school year opens. Among the new teachers will be Charles H. Houston, of this city, a graduate of Amherst and of the Harvard Law school, who has for the last year pursued graduate law studies in Spain. He will have a place on the law school faculty.

[end of article]

Houston was singled out in a short announcement in The Washington Post of the number of Howard faculty appointed in fall 1924. The piece highlighted his degree from Harvard Law School as well as his time studying abroad. “Additions Approved to Howard Faculty.” July 27, 1924/Public Domain

Open and scroll to read the article transcript

[single column newsprint article; spelling and typographical errors preserved; formatting preserved wherever possible]

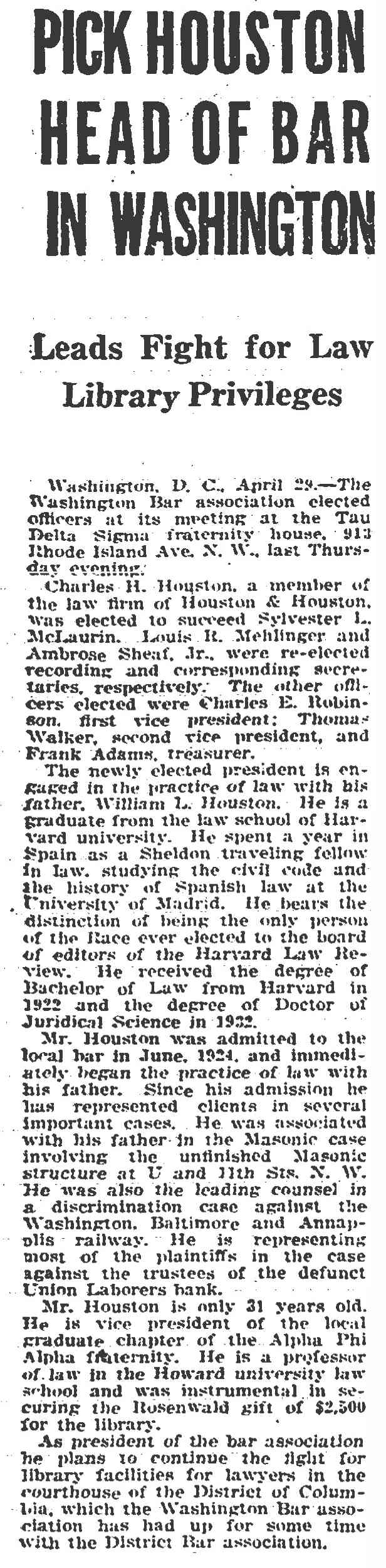

PICK HOUSTON HEAD OF BAR IN WASHINGTON

Leads Fight for Law Library Privileges

Washington, D. C. April 29. — The Washington Bar association elected officers at its meeting at the Tau Delta Sigma fraternity house, 913 Rhode Island Ave. N. W., last Thursday evening.

Charles H. Houston, a member of the law firm of Houston & Houston, was elected to succeed Sylvester L. McLaurin. Louis R. Mehlinger and Ambrose Sheaf, Jr., were re-elected recording and corresponding secretaries, respectively. The other officers elected were Charles E. Robinson, first vice president; Thomas Walker, second vice president, and Frank Adams, treasurer.

The newly elected president is engaged in the practice of law with his father, William L. Houston. He is a graduate from the law school of Harvard university. He spent a year in Spain as a Sheldon traveling fellow in law, studying the civil code and the history of Spanish law at the University of Madrid. He bears the distinction of being the only person of the Race ever elected to the board of editors of the Harvard Law Review. He received the degree of Bachelor of Law from Harvard in 1922 and the degree of Doctor of Juridical Science in 1932.

Mr. Houston was admitted to the local bar in June, 1924, and immediately began the practice of law with his father. Since his admission he has represented clients in several important cases. He was associated with his father in the Masonic case involving the unfinished Masonic structure at U and 11th Sts. N. W. He was also the leading counsel in a discrimination case against the Washington, Baltimore and Annapolis railway. He is representing most of the plaintiffs in the case against the trustees of the defunct Union Laborers bank.

Mr. Houston is only 31 years old. He is vice president of the local graduate chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity. He is a professor of law in the Howard university law school and was instrumental in securing the Rosenwald gift of $2,500 for the library.

As president of the bar association he plans to continue the fight for library facilities for lawyers in the courthouse of the District of Columbia, which the Washington Bar association has had up for some time with the District Bar association.

[end of article]

In addition to his teaching and administrative work at Howard Law School, Houston was a leader in the community of Black attorneys in Washington, DC. “Pick Houston Head of Bar in Washington: Leads Fight for Law Library Privileges.” The Chicago Defender. April 30, 1927/Public Domain

Fighting Segregation

Houston left Howard in 1935 to serve as the NAACP’s first general counsel, establishing a precursor to Marshall’s Legal Defense and Educational Fund. He made it his mission to disprove the fallacy of “separate but equal” and launched a nationwide campaign by Black lawyers to expose the glaring inequities that Black Americans faced in all aspects of their lives, particularly education. To make his case and attract people to his cause, Houston traveled throughout the South documenting these inequities on film and delivered speeches across the nation, arguing that,

Discrimination in education is symbolic of all the more drastic discriminations which Negroes suffer in American life. And these apparent senseless discriminations in education against Negroes have a very definite objective on the part of the ruling whites, to curb the young Negroes and prepare them to accept an inferior position in American life without protest or struggle.

Houston also won major cases affirming the civil rights of Black Americans in other areas. Of the eight cases that he argued before the U.S. Supreme Court, he won seven.

Houston died in 1950. He did not get to argue or see the benefits of the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision.

Houston led the legal fight for Black equality for more than 20 years, winning major cases affirming the civil rights of Black people in education and other areas. Of eight cases that he argued before the U.S. Supreme Court, he won seven. “Charles H. Houston in court.” Charles Hamilton Houston Papers/Courtesy of the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University Archives

Open and scroll to read the poster transcript

[text and black and white images on plain background; spelling and typographical errors preserved; formatting preserved wherever possible]

STOP THIS!!

[horizontal line border]

[left side: photograph of the head of a light-skinned man with visible injuries to his face and bandage wrapped around his head covering his forehead]

[photo caption] Frank A. Mielke

[right side: photograph of a dark-skinned adult man in a suit standing next to a seated dark-skinned teen boy; the man has his hand on the teen’s shoulder, and the teen is pointing with one finger to his jaw as he looks at the man]

[photo caption] Jasper Choice

These Men were beaten by Detroit Police officers without cause!

[horizontal line border]

NICK KOBANE is paralyzed from his waist down, he was shot by a policeman.

JESSE JAMES was killed in cold blood.

LEO LOTHRIDGE, a 15-year-old boy was also killed.

[horizontal line border]

YOU MAY BE NEXT

ATTEND MASS MEETING

At BETHEL A. M. E. CHURCH

SUNDAY, JULY 23, at 3:30pm

HEAR THE FACTS — SUCH BRUTALITIES MUST BE STOPPED.

Attorney Charles H. Houston

Of Washington, D. C., Guest Speaker

PUBLIC INVITED ADMISSION FREE

[end of flyer]

Houston made it his mission to disprove the fallacy of “separate but equal” and spearheaded a nationwide campaign by Black lawyers to expose the glaring inequities that Black Americans faced in all aspects of their lives. “Stop This!!” Flyer. ca. 1939. Charles Hamilton Houston Papers/Courtesy of the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University Archive

A Living Legacy: The Work Continues

In 2005, Harvard Law School professor Charles J. Ogletree, Jr., launched the Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race and Justice at Harvard Law School. The center not only honors Houston but also continues his unfinished work combatting discrimination and securing equal rights and opportunity. As Houston himself reflected in a recording made near the end of his life, “It is necessary to establish the principle of the indivisibility of liberty, so that the masses recognize that no matter where liberty is challenged, no matter where oppression lifts its head, it becomes the business of all the masses.” He went on,

[…] the Negro shall not be content simply with demanding an equal share in the existing system. It seems to me that his fundamental responsibility and his historical challenge is to use his weight […] to make sure that the system which shall survive in the United States of America—I don’t care what system you call it — shall be a system which guarantees justice and freedom for everyone.

Selected Sources

Anderson, José Felipé. Genius for Justice. Durham, North Carolina: Carolina Academic Press, LLC, 2021.

Carter, Robert L. et al.. “In Tribute: Charles Hamilton Houston,” Harvard Law Review 111, no. 8 (1998): 2149–2179.

“Charles Hamilton Houston.” NAACP. Accessed October 5, 2023.

“Charles Hamilton Houston” and “Preparing for the Struggle.” Separate Is Not Equal: Brown v. Board of Education. Smithsonian National Museum of American History. Accessed October 5, 2023.

Houston, Charles H. “The Need for Negro Lawyers.” The Journal of Negro Education 4, no. 1 (1935): 49–52.

Houston, Charles Hamilton. “Personal Recording, 1949.” In Say It Plain: A Century of Great African American Speeches, edited by Catherine Ellis and Stephen Drury Smith, 21–28. New York: The New Press, 2005.

Houston, Charles Hamilton. “Saving the World for ‘Democracy.’” The Pittsburgh Courier (1911–1950). July 21–October 12, 1940. Retrieved from ProQuest.

McNeil, Genna Rae and A. Leon Higginbotham Jr. Groundwork: Charles Hamilton Houston and the Struggle for Civil Rights. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1984.

Milano, Brett. “The man who killed Jim Crow: The legacy of Charles Hamilton Houston.” Harvard Law Today. September 5, 2019.

Pearson, Albert M. 2018. “Charles Hamilton Houston: Mockingbird with Talons.” Howard Law Journal 61 (2): 319–339.

More profiles

Richard T. Greener

Harvard College’s first Black graduate, Richard T. Greener went on to become the first Black professor at the University of South Carolina and dean of the Howard University School of Law.

Ewart Guinier

Ewart G. Guinier was the founding chair of Harvard’s first Department of Afro-American Studies in 1969—a bittersweet return to Harvard decades after he faced a dispiriting student experience from 1929 to 1931. Guinier devoted his…

Carter G. Woodson

Carter G. Woodson, known as “The Father of Black History,” was the second African American to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard University. He created Negro History Week — the forerunner to Black History Month —…