Work to analyze 17th, 18th, and 19th century records creates deeper understanding of University’s impact on Tribal lands and Indigenous peoples

By Nicole Rura | September 30, 2025

This summer, Laura Cleves and Christiano Topinio delved into the University Archives and other archival resources to expand understanding of the University’s historical entanglements with Indigenous peoples. The two inaugural Caleb Cheeshahteaumuck and Joel Iacoombs Fellows analyzed 17th, 18th, and 19th century legal documents and land deeds to trace part of Harvard’s land holdings in Maine during the colonial period.

Cleves and Topinio’s research will be integrated into the Harvard & Native Lands course created by Leverett Saltonstall Professor of History Philip Deloria and Alan Niles, visiting lecturer in English and a scholar in early colonial American history.

Over the past three years, students in Deloria and Niles’ class have conducted original research on Harvard’s history of involvement with Indigenous communities and Native lands, including Natives lands in Harvard’s endowment. Cleves and Topinio’s contributions through the new fellowships are a continuation of this scholarship, which collectively creates a foundation for future research and for the University to better understand its past.

“Harvard’s history is really interesting and complex, and it’s much richer in Native history than people realize,” said Deloria, who is one of the fellows’ mentors and a member of Harvard & the Legacy of Slavery (H&LS) Initiative’s Advisory Council. “We have a picture of what 18th century Harvard looks like, but we don’t have a picture of the ways that the institution was changing and being shaped and formed in those early moments.”

The fellowships are funded by the Inequality in America Initiative and Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellowship, and supported by the Harvard Office of Undergraduate Research and Fellowships (URAF) through the Summer Undergraduate Research Village’s (HSURV) BLISS program, a nine-week summer residential program that provides substantive social science research experience for Harvard undergraduates.

The fellowships, which are open to Harvard undergraduates interested in Native and archival research, are named in honor of Caleb Cheeshahteaumuck and Joel Iacoombs, who were both members of the Wampanoag Tribe of Aquinnah and the Class of 1665. Cheeshahteaumuck was one of five Native students who attended Harvard’s Indian College, and the only to earn a degree. Iacoombs completed his four-year studies at Harvard but died in a shipwreck weeks before he could participate in Commencement. His special degree was posthumously awarded in 2011.

To expand research on Harvard’s involvement with Native lands and establish the fellowships, Emanuel Contomanolis, associate dean of undergraduate education and academic engagement, worked with Deloria, Jordan Clark, executive director of Harvard University Native American Program (HUNAP), and Sara Bleich, vice provost for special projects and leader of Harvard & the Legacy of Slavery (H&LS) Initiative.

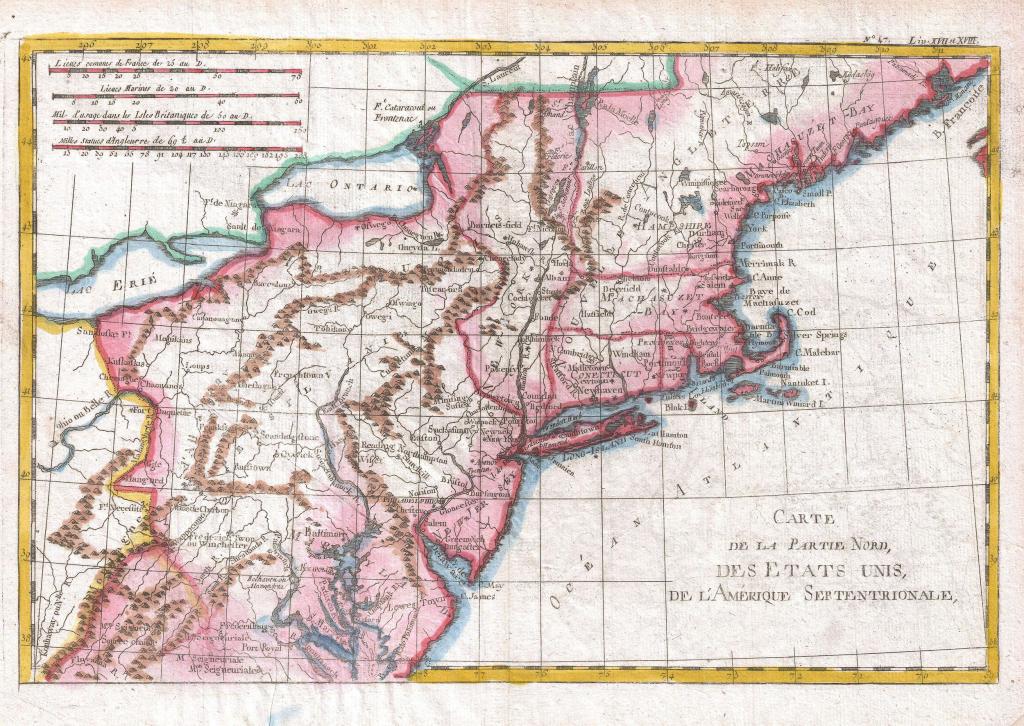

A look at the research: Disputed understanding of land titles and deeds

Throughout its early history, Harvard acquired and was given land through various means. The Province of Massachusetts Bay–called the Commonwealth of Massachusetts after the American Revolution–employed various methods to financially bolster the University, including granting it lands as far away as what is now Maine. Land was also bequeathed or given to the University by alumni. Harvard could benefit from this land by selling or leasing it, or extracting its resources, such as timber. Beyond reaping financial rewards, Harvard also benefitted from colonial laws and speculative land markets that were emerging at the time.

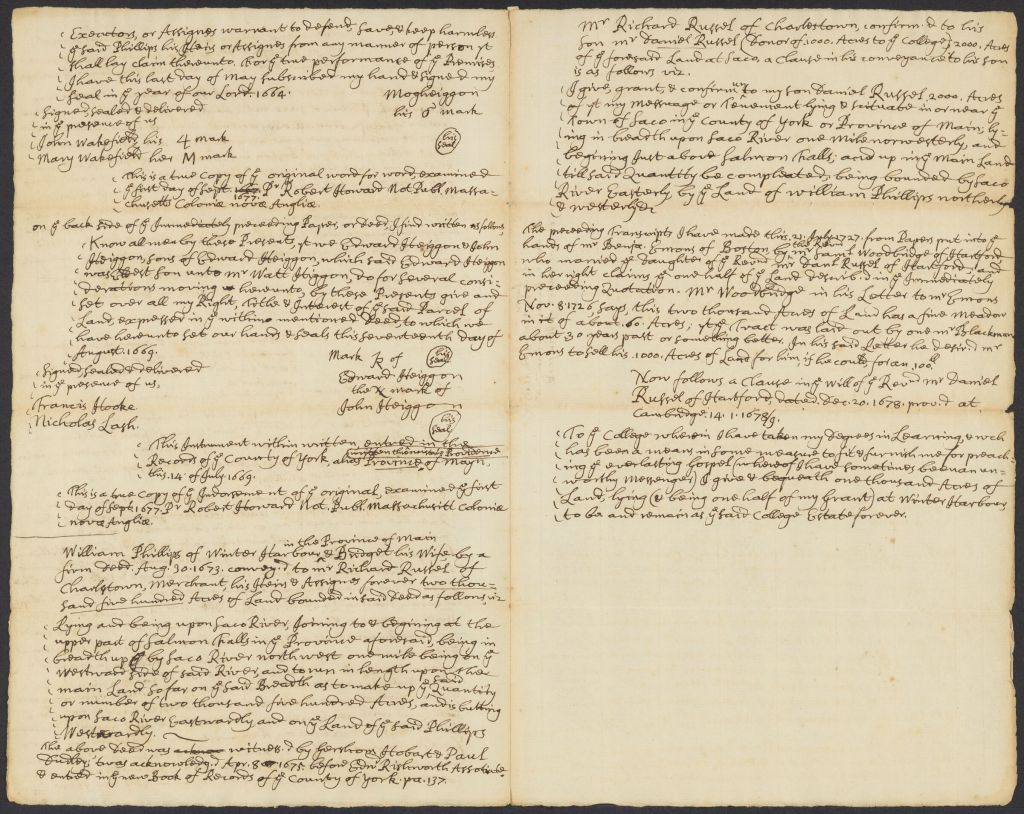

Records of these land transactions were carefully preserved in the University Archives, Massachusetts State Archives, and other institutions’ archives, but the fellows’ analysis provided fuller context for these records.

“We knew that we had these documents in the University Archives, but it takes scholarly work to read the 18th century handwriting, decipher the legal language, and understand the deeper information that these records contain,” said University Archivist Virgina Hunt.

Under the mentorship of Deloria, Niles, and Kabl Wilkerson, a doctoral candidate in the Department of History, Cleves and Topinio investigated the important question: How did Harvard University sponsor and benefit from the colonial project in New England with regard to Native communities?

According to Cleves and Topinino’s work, Rev. Daniel Russell, who graduated from the College in 1665, bequeathed 1,000 acres of land to Harvard in 1678. The parcel, where Hollis, Maine, is today, had been initially sold by Sachem Hombinowitt of the Penobscot Nation to Major William Phillips in 1660. Phillips and his wife sold portions of the land to two families, including Richard Russell, Daniel Russell’s father.

Russell’s bequest to Harvard was ignored for decades until 1788, when Jeremiah Hill, who graduated from Harvard in 1780, advised Harvard’s leadership to sell the parcel. To expedite the sale, Harvard distributed 62 acres to placate white squatters who had been living on the land and may have had a claim to it. Harvard sold the remaining 938 acres in 1807 for the sum of $1,877, which would be about $54,000 if sold today.

Often “Indian deeds”, such as the agreement between Hobinowitt and Phillips, obscure complicated histories and disagreements, according to Niles. In the 18th century, Maine Tribal leaders disputed that earlier agreements with English leaders had given settlers exclusive rights to the land. The Tribal leaders insisted that their consent to English uses of the land depended on continuing reciprocal relationships. Even after Harvard acquired its bequest, the Indigenous people of that area continued to live on and make use of what they considered their land, said Niles.

“Christian and Laura’s research shows that although Harvard did not purchase this land, it participated in and derived some financial benefit from structures and processes that ultimately pushed Penobscot, Abenaki, and other Northeast peoples off their lands—including a new colonial market for land and the transformation of land into an instrument of financial speculation,” said Niles.

One piece of the puzzle

Cleves and Topinio presented their research to fellow HSURV researchers on August 6. The fellows said that their work with archivists, librarians, other historians, and Native peoples was inspirational and provided insights into Harvard’s history that surprised them.

“I found it fascinating how much archival documents can affect how we tell a narrative, and how those narratives ultimately influence, at least in this case, Harvard’s own understanding of its history of entanglement with Native lands, especially in Maine,” said Cleves, a sophomore planning a joint concentration in Social Studies, and Environmental Science and Public Policy.

Topinio, a junior concentrating in Social Studies and English, said the archival research was coupled with conversations with members of the Penobscot Nation that improved the fellows’ interpretation of the archival content.

“Navigating the Archives themselves was incredibly useful, as was taking a trip to Maine and hearing from people of the Penobscot Nation,” he said. “Talking with them was so valuable. We heard so many stories about the land, about its history, about the pain of what happened to people of the Penobscot Nation, and about effects of the United States’ actions during its colonial era.”

According to Deloria, future research could pursue many avenues, including broader analysis of transactions in Maine and other parts of New England and expanding the studied time period from the early colonial era into the early 19th century.

Wilkerson, who guided Cleves and Topinio’s work throughout the summer, said the fellows’ research will help shape future efforts to uncover Harvard’s colonial history.

“Their research is not definitive and gave us a lot of questions for future generations of researchers and other students to pursue. It’s truly just one piece of a much larger project,” Wilkerson said.